A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| |

| Geographical range | Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Chalcolithic |

| Dates | c. 3000 BC – c. 2350 BC |

| Major sites | Bronocice |

| Preceded by | Yamnaya culture, Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, Globular Amphora culture, Funnelbeaker culture, Baden culture, Horgen culture, Volosovo culture, Narva culture, Pit–Comb Ware culture, Pitted Ware culture |

| Followed by | Bell Beaker culture, Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture, Abashevo culture, Sintashta culture, Mierzanowice culture,[1] Unetice culture, Nordic Bronze Age, Komarov culture |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between c. 3000 BC – 2350 BC, thus from the late Neolithic, through the Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age.[2] Corded Ware culture encompassed a vast area, from the contact zone between the Yamnaya culture and the Corded Ware culture in south Central Europe, to the Rhine in the west and the Volga in the east, occupying parts of Northern Europe, Central Europe and Eastern Europe.[2][3] Early autosomal genetic studies suggested that the Corded Ware culture originated from the westward migration of Yamnaya-related people from the steppe-forest zone into the territory of late Neolithic European cultures;[4][5][6] however, paternal DNA evidence fails to support this hypothesis, and it is now proposed that the Corded Ware culture evolved in parallel with (although under significant influence from) the Yamnaya, with no evidence of direct male-line descent between them.[7]

The Corded Ware culture is considered to be a likely vector for the spread of many of the Indo-European languages in Europe and Asia.[1][8][9][10]

Nomenclature

The term Corded Ware culture (German: Schnurkeramik-Kultur) was first introduced by the German archaeologist Friedrich Klopfleisch in 1883.[11] He named it after cord-like impressions or ornamentation characteristic of its pottery.[11] The term Single Grave culture comes from its burial custom, which consisted of inhumation under tumuli in a crouched position with various artifacts. Battle Axe culture, or Boat Axe culture, is named from its characteristic male grave offering, a stone boat-shaped battle axe.[11]

Geography

Corded Ware encompassed most of continental northern Europe from the Rhine in the west to the Volga in the east, including most of modern-day Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Slovakia, Switzerland, northwestern Romania, northern Ukraine, and the European part of Russia, as well as coastal Norway and the southern portions of Sweden and Finland.[2] In the Late Eneolithic/Early Bronze Age, it encompassed the territory of nearly the entire Balkan Peninsula, where Corded Ware mixed with other steppe elements.[13]

Archaeologists note that Corded Ware was not a "unified culture," as Corded Ware groups inhabiting a vast geographical area from the Rhine to Volga seem to have regionally specific subsistence strategies and economies.[2]: 226 There are differences in the material culture and in settlements and society.[2] At the same time, they had several shared elements that are characteristic of all Corded Ware groups, such as their burial practices, pottery with "cord" decoration and unique stone-axes.[2]

The contemporary Bell Beaker culture overlapped with the western extremity of this culture, west of the Elbe, and may have contributed to the pan-European spread of that culture. Although a similar social organization and settlement pattern to the Beaker were adopted, the Corded Ware group lacked the new refinements made possible through trade and communication by sea and rivers.[14]

Origins

The origins and dispersal of Corded Ware culture is one of the pivotal unresolved issues of the Indo-European Urheimat problem,[15] and there is a stark division between archaeologists regarding the origins of Corded Ware. The Corded Ware culture has long been regarded as Indo-European, with archaeologists seeing an influence from nomadic pastoral societies of the steppes. Alternatively, some archaeologists believed it developed independently in central Europe.[16]

Relation with Yamnaya culture

The Corded Ware culture was once presumed to be the Urheimat of the Proto-Indo-Europeans based on their possession of the horse and wheeled vehicles, apparent warlike propensities, wide area of distribution and rapid intrusive expansion at the assumed time of the dispersal of Indo-European languages.[15] Today this specific idea has lost currency, as the steppe hypothesis is currently the most widely accepted proposal to explain the origins and spread of the Indo-European languages.[16]

Autosomal genetic studies suggest that the people of the Corded Ware culture share significant levels of ancestry with Yamnaya as a consequence of a "massive migration" from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, and the people of both cultures may be directly descended from a genetically similar pre-Yamnaya population.[8][6]

Kristiansen et al. (2017) theorise that the Corded Ware culture originated from male Yamnaya pastoralists who migrated northward and married women from farming communities.[17][note 1] However, Barry Cunliffe has criticized the theory that the Corded Ware populations were descended from a mass migration of Yamnaya males, noting that the available Corded Ware samples do not carry paternal haplogroups observed in Yamnaya male specimens.[18] This view is shared by Leo Klejn, who maintains that "the Yamnaya cannot be the source of the Corded Ware cultures", as the Corded Ware paternal haplogroups are unrelated to those found in Yamnaya specimens.[19][20][note 2]

In 2023, Kristiansen et al. acknowledged that the lack of Yamnaya male ancestry in Corded Ware populations indicates that they cannot have been descended from the Yamnaya directly. These authors now propose that the Corded Ware populations evolved in parallel with Yamnaya.[7] Previously, Guus Kroonen et al. (2022), had argued that the Corded Ware populations may have originated from a Yamnaya-related population, rather than the Yamnaya themself, stating that "this may support a scenario of linguistic continuity of local non-mobile herders in the Lower Dnieper region and their genetic persistence after their integration into the successive and expansive Yamnaya horizon".[22]

Archaeologists Furholt and Heyd continue to emphasize the differences both between and within the material cultures of these two groups, as well as emphasizing the problems of oversimplifying these long-term social processes.[23][24]

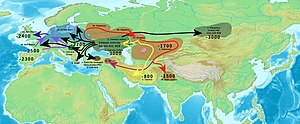

The Middle Dnieper culture forms a bridge between the Yamnaya culture and the Corded Ware culture. From the Middle Dnieper culture the Corded Ware culture spread both west and east. The eastward migration gave rise to the Fatyanova culture which had a formative influence on the Abashevo culture, which in turn contributed to the proto-Indo-Iranian Sintashta culture.[3] Its wide area of distribution indicates rapid expansion at the assumed time of the dispersal of the core (excluding Anatolian and Tocharian) Indo-European languages. In a number of regions Corded Ware appears to herald a new culture and physical type.[15] On most of the immense, continental expanse that it covered, the culture was clearly intrusive, and therefore represents one of the most impressive and revolutionary cultural changes attested by archaeology.[14]

Independent development

In favour of the view that the culture developed independently was the fact that Corded Ware coincides considerably with the earlier north-central European Funnelbeaker culture (TRB). According to Gimbutas, the Corded Ware culture was preceded by the Globular Amphora culture (3400–2800 BC), which she regarded to be an Indo-European culture. The Globular Amphora culture stretched from central Europe to the Baltic sea, and emerged from the Funnelbeaker culture.[25]

According to controversial radiocarbon dates, Corded Ware ceramic forms in single graves develop earlier in the area that is now Poland than in western and southern Central Europe.[26] The earliest radiocarbon dates for Corded Ware indeed come from Kujawy and Lesser Poland in central and southern Poland and point to the period around 3000 BC.

However, subsequent review has challenged this perspective, instead pointing out that the wide variation in dating of the Corded Ware, especially the dating of the culture's beginning, is based on individual outlier graves, is not particularly in line with other archaeological data and runs afoul of plateaus in the radiocarbon calibration curve; in the one case where the dating can be clarified with dendrochronology, in Switzerland, Corded Ware is found for only a short period from 2750 BC to 2400 BC.[27] Furthermore, because the short period in Switzerland seems to represent examples of artifacts from all the major sub-periods of the Corded Ware culture elsewhere, some researchers conclude that Corded Ware appeared more or less simultaneously throughout North Central Europe approximately in the early 29th century BC (around 2900 BC), in a number of "centers" which subsequently formed their own local networks.[2]: 297 Carbon-14 dating of the remaining central European regions shows that Corded Ware appeared after 2880 BC.[28] According to this theory, it spread to the Lüneburg Heath and then further to the North European Plain, Rhineland, Switzerland, Scandinavia, the Baltic region and Russia to Moscow, where the culture met with the pastoralists considered indigenous to the steppes.[14]

Subgroups

Middle Dnieper culture

The Middle Dnieper culture is a formative early expression of the Corded Ware culture.[3] It has very scant remains, but occupies the easiest route into Central and Northern Europe from the steppe.

Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture

The Middle Dnieper culture and the Eastern Baltic Corded Ware culture gave rise to the Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture on the upper Volga,[3] which in turn contributed to the Abashevo culture, a predecessor of the proto-Indo-Iranian Sintashta culture.

The Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture may have been a culture with an Indo-European superstratum over a Uralic substratum,[citation needed] and may account for some of the linguistic borrowings identified in the Indo-Uralic thesis. However, according to Häkkinen, the Uralic–Indo-European contacts only start in the Corded Ware period and the Uralic expansion into the Upper Volga region postdates it. Häkkinen accepts Fatyanovo-Balanovo as an early Indo-European culture, but maintains that their substratum (identified with the Volosovo culture) was neither Uralic nor Indo-European.[29]

Schnurkeramikkultur

The prototypal Corded Ware culture, German Schnurkeramikkultur, is found in Central Europe, mainly Germany and Poland, and refers to the characteristic pottery of the era: twisted cord was impressed into the wet clay to create various decorative patterns and motifs. It is known mostly from its burials, and both sexes received the characteristic cord-decorated pottery. Whether made of flax or hemp, they had rope.

Single Grave culture

Single Grave term refers to a series of late Neolithic communities of the 3rd millennium BC living in southern Scandinavia, Northern Germany, and the Low Countries that share the practice of single burial, the deceased usually being accompanied by a battle-axe, amber beads, and pottery vessels.[30]

The term Single Grave culture was first introduced by the Danish archaeologist Andreas Peter Madsen in the late 1800s. He found Single Graves to be quite different from the already known dolmens, long barrows and passage graves.[31] In 1898, archaeologist Sophus Müller was first to present a migration-hypothesis stating that previously known dolmens, long barrows, passage graves and newly discovered single graves may represent two completely different groups of people, stating "Single graves are traces of new, from the south coming tribes".[32]

The cultural emphasis on drinking equipment already characteristic of the early indigenous Funnelbeaker culture, synthesized with newly arrived Corded Ware traditions. Especially in the west (Scandinavia and northern Germany), the drinking vessels have a protruding foot and define the Protruding-Foot Beaker culture (PFB) as a subset of the Single Grave culture.[33] The Beaker culture has been proposed to derive from this specific branch of the Corded Ware culture.[citation needed]

The Danish-Swedish-Norwegian Battle Axe culture, or the Boat Axe culture, appeared c. 2800 BC and is known from about 3,000 graves from Scania to Uppland and Trøndelag. The "battle-axes" were primarily a status object. There are strong continuities in stone craft traditions, and very little evidence of any type of full-scale migration, least of all a violent one. The old ways were discontinued as the corresponding cultures on the continent changed, and the farmers living in Scandinavia took part in a few of those changes since they belonged to the same network. Settlements on small, separate farmsteads without any defensive protection is also a strong argument against the people living there being aggressors.

About 3000 battle axes have been found, in sites distributed over all of Scandinavia, but they are sparse in Norrland and northern Norway. Less than 100 settlements are known, and their remains are negligible as they are located on continually used farmland, and have consequently been plowed away. Einar Østmo reports sites inside the Arctic Circle in the Lofoten, and as far north as the present city of Tromsø.

The Swedish-Norwegian Battle Axe culture was based on the same agricultural practices as the previous Funnelbeaker culture, but the appearance of metal changed the social system. This is marked by the fact that the Funnelbeaker culture had collective megalithic graves with a great deal of sacrifices to the graves, but the Battle Axe culture has individual graves with individual sacrifices.

A new aspect was given to the culture in 1993, when a death house in Turinge, in Södermanland was excavated. Along the once heavily timbered walls were found the remains of about twenty clay vessels, six work axes and a battle axe, which all came from the last period of the culture. There were also the cremated remains of at least six people. This is the earliest find of cremation in Scandinavia and it shows close contacts with Central Europe.

In the context of the entry of Germanic into the region, Einar Østmo emphasizes that the Atlantic and North Sea coastal regions of Scandinavia, and the circum-Baltic areas were united by a vigorous maritime economy, permitting a far wider geographical spread and a closer cultural unity than interior continental cultures could attain. He points to the widely disseminated number of rock carvings assigned to this era, which display "thousands" of ships. To seafaring cultures like this one, the sea is a highway and not a divider.[34]

Finnish Battle Axe culture

The Finnish Battle Axe culture was a mixed cattle-breeder and hunter-gatherer culture, and one of the few in this horizon to provide rich finds from settlements.

Economy

There are very few discovered settlements, which led to the traditional view of this culture as exclusively nomadic pastoralists, similar to that of the Yamnaya culture, and the reconstructed culture of the Indo-Europeans as inferred from philology.

However, this view was modified, as some evidence of sedentary farming emerged. Traces of emmer, common wheat and barley were found at a Corded Ware site at Bronocice in south-east Poland. Wheeled vehicles (presumably drawn by oxen) are in evidence, a continuation from the Funnelbeaker culture era.[15][35]

Cows' milk was used systematically from 3400 BC onwards in the northern Alpine foreland. Sheep were kept more frequently in the western part of Switzerland due to the stronger Mediterranean influence. Changes in slaughter age and animal size are possibly evidence for sheep being kept for their wool at Corded Ware sites in this region.[36]

Graves

Burial occurred in flat graves or below small tumuli in a flexed position; on the continent males lay on their right side, females on the left, with the faces of both oriented to the south. However, in Sweden and also parts of northern Poland the graves were oriented north-south, men lay on their left side and women on the right side - both facing east. Originally, there was probably a wooden construction, since the graves are often positioned in a line. This is in contrast with practices in Denmark where the dead were buried below small mounds with a vertical stratigraphy: the oldest below the ground, the second above this grave, and occasionally even a third burial above those. Other types of burials are the niche-graves of Poland. Grave goods for men typically included a stone battle axe. Pottery in the shape of beakers and other types are the most common burial gifts, generally speaking. These were often decorated with cord, sometimes with incisions and other types of impressions. Other grave goods also included wagons and sacrificed animals.

The approximately contemporary Beaker culture had similar burial traditions, and together they covered most of Western and Central Europe. The Beaker culture originated around 2800 BC in the Iberian Peninsula and subsequently extended into Central Europe, where it partly coexisted with the Corded Ware region.

In April 2011, it was reported that an untypical Corded Ware burial had been discovered in a suburb of Prague.[37] The remains, believed to be male, were orientated in the same way as women's burials and were not accompanied by any gender-specific grave goods. Based on this, and the importance usually attached to funeral rites by people from this period, the archaeologists suggested that this was unlikely to be accidental, and conclude that it was likely that this individual "was a man with a different sexual orientation, homosexual or transsexual",[37] while media reports heralded the discovery of the world's first "gay caveman".[38] Archaeologists and biological anthropologists criticised media coverage as sensationalist. "If this burial represents a transgendered [sic] individual (as well it could), that doesn't necessarily mean the person had a 'different sexual orientation' and certainly doesn't mean that he would have considered himself (or that his culture would have considered him) 'homosexual,'" anthropologist Kristina Killgrove commented.[39] Other items of criticism were that someone buried in the Copper Age was not a "caveman" and that identifying the sex of skeletal remains is difficult and inexact.[40] Turek notes that there are several examples of Corded Ware graves containing older biological males with typically female grave goods and body orientation. He suggests that "aged men may have decided to 'retire' as women for symbolic and practical reasons."[41] A detailed account of the burial has not yet appeared in scientific literature.

Gallery

-

Pottery and axes, Germany

-

Necklace, Czech Republic

-

Amber disk and beads from Denmark

-

Battle Axe culture ceramics

-

Pottery, Germany

-

Belt plates made from bone

-

Beaker, axes and footed bowls, Germany

-

Corded Ware vessels, Czech Republic

-

Copper finger ring, Germany, c. 2750 BC

-

Copper dagger, awl and bone pin, Germany

-

Corded Ware amphora, Germany

-

Necklaces made from shell beads, Czech Republic

-

Ring made from antler, Germany

-

Amber disc with sun cross symbol (illustration)

Theories regarding linguistic identity

Spread of Indo-European languages

The Corded Ware culture may have played a central role in the spread of the Indo-European languages in Europe during the Copper and Bronze Ages.[42][43] It had often been suggested that the CWC represented the geolinguistic core of the Indo-European languages subsequent to the divergence of first the Anatolian and Tocharian languages and later a group ancestral to the Indo-Iranian, Greek, Armenian, Illyrian and/or Thracian languages; such models implied the CWC spoke a language ancestral to the Italo-Celtic, Germanic, and Balto-Slavic languages.[44] According to Mallory (1999), the Corded Ware culture may have been "the common prehistoric ancestor of the later Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, and possibly some of the Indo-European languages of Italy."[44] Mallory (1999) also suggests that Corded Ware could not have been the sole source for Greek, Illyrian, Thracian and East Italic, which may be derived from Southeast Europe.[44] Mallory (2013) proposes that the Beaker culture was associated with a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-West Indo-European", spreading northwards from the Alpine regions and ancestral to not only Celtic but equally Italic, Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[45]

According to Anthony (2007), the Corded Ware horizon may have introduced Germanic, Baltic and Slavic into northern Europe.[46] According to Anthony, the Pre-Germanic dialects may have developed in the Usatovo culture in south-eastern Central Europe between the Dniestr and the Vistula between c. 3100 and 2800 BC, and spread with the Corded Ware culture.[47] Between 3100 and 2800/2600 BC, a real folk migration of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamnaya culture took place into the Danube Valley,[48] which eventually reached as far as Hungary,[49] where pre-Celtic and pre-Italic may have developed.[46] Slavic and Baltic developed at the middle Dniepr (present-day Ukraine).[50]

Haak et al. (2015) envision a migration from the Yamnaya culture into Germany.[51] Allentoft et al. (2015) envision a migration from the Yamnaya culture towards north-western Europe via Central Europe, and towards the Baltic area and the eastern periphery of the Corded Ware culture via the territory of present-day Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.[1]

Theoretical explanation: language shift

According to Gimbutas' original theory, the process of "Indo-Europeanization" of Corded Ware (and, later, the rest of Europe) was essentially a cultural transformation, not a genetic one.[52] The Yamnaya migration from Eastern to Central and Western Europe is understood by Gimbutas as a military victory, resulting in the Yamnaya imposing a new administrative system, language and religion upon the indigenous groups.[53][a][b]

David Anthony (2007), in his "revised Steppe hypothesis",[54] proposes that the spread of the Indo-European languages probably did not happen through "chain-type folk migrations," but by the introduction of these languages by ritual and political elites, which were emulated by large groups of people,[55] a process which he calls "elite recruitment".[56][c] Yet, in supplementary information to Haak et al. (2015), Anthony, together with Lazaridis, Haak, Patterson, and Reich, notes that the mass migration of Yamnaya people to northern Europe shows that "the Steppe hypothesis does not require elite dominance to have transmitted Indo-European languages into Europe. Instead, our results show that the languages could have been introduced simply by strength of numbers: via major migration in which both sexes participated."[57][d]

Linguist Guus Kroonen points out that speakers of Indo-European languages encountered existing populations in Europe that spoke unrelated, non-Indo-European languages when they migrated further into Europe from the Yamnaya culture's steppe zone at the margin of Europe.[58] He focuses on both the effects on Indo-European languages that resulted from this contact and investigation of the pre-existing languages. Relatively little is known about the Pre-Indo-European linguistic landscape of Europe, except for Basque, as the "Indo-Europeanization" of Europe caused a massive and largely unrecorded linguistic extinction event, most likely through language shift.[59] Kroonen's 2015[59] study claims to show that Pre-Indo-European speech contains a clear Neolithic signature emanating from the Aegean language family and thus patterns with the prehistoric migration of Europe’s first farming populations.[59]: 10

Marija Gimbutas, as part of her theory, had already inferred that the Corded Ware culture's intrusion into Scandinavia formed a synthesis with the indigenous people of the Funnelbeaker culture, giving birth to the Proto-Germanic language.[52] According to Edgar Polomé, 30% of the non-Indo-European substratum found in the modern German language derives from non-Indo-European-speakers of Funnelbeaker culture, indigenous to southern Scandinavia.[60] She claimed that when Yamnaya Indo-European speakers came into contact with the indigenous peoples during the 3rd millennium BC, they came to dominate the local populations yet parts of the indigenous lexicon persisted in the formation of Proto-Germanic, thus giving Proto-Germanic the status of being an "Indo-Europeanized" language.[61] However, more recent linguists[citation needed] have substantially reduced the number of roots claimed to be uniquely Germanic, and more recent treatments of Proto-Germanic tend to reject or simply omit discussion of the Germanic substrate hypothesis, giving little reason to consider Germanic anything but a typical Indo-European dialect with at most minor substrate influence.

Genetic studies

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (April 2024) |

Relation with Yamnaya-culture

Haak et al. (2015) found that a large proportion of the ancestry of the Corded Ware culture's population is similar to that of the Yamnaya culture, tracing the Corded Ware culture's origins to a "massive migration" of the Yamnaya or an earlier (pre-Yamnaya) population from the steppes 4,500 years ago.[8] The DNA of late Neolithic Corded Ware skeletons found in Germany was found to be around 75% similar to DNA from individuals of the Yamnaya culture.[8] Yet, Haak et al. (2015) warned:[8]

We caution that the sampled Yamnaya individuals from Samara might not be directly ancestral to Corded Ware individuals from Germany. It is possible that a more western Yamnaya population, or an earlier (pre-Yamnaya) steppe population may have migrated into central Europe, and future work may uncover more missing links in the chain of transmission of steppe ancestry.

— W. Haak et al., Nature (2015)

The same study estimated a 40–54% ancestral contribution of so-called "steppe ancestry" in the DNA of modern Central & Northern Europeans, and a 20–32% contribution in modern Southern Europeans, excluding Sardinians (7.1% or less), and to a lesser extent Sicilians (11.6% or less).[8][62][63] Haak et al. (2015) further found that autosomal DNA tests indicate that westward migration from the steppes was responsible for the introduction of a component of ancestry referred to as "Ancient North Eurasian" admixture into western Europe.[8] "Ancient North Eurasian" is the name given in genetic literature to a component that represents descent from the people of the Mal'ta-Buret' culture[8] or a population closely related to them.[8] The "Ancient North Eurasian" genetic component is visible in tests of the Yamnaya people[8] as well as modern-day Europeans, but not of Western or Central Europeans predating the Corded Ware culture.[64]

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Lead section#Length

Wikipedia:Summary style

Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Lead section#Provide an accessible overview

File:Corded Ware culture.jpg

Europe

Chalcolithic Europe

Bronocice

Yamnaya culture

Cucuteni-Trypillia culture

Globular Amphora culture

Funnelbeaker culture

Baden culture

Horgen culture

Volosovo culture

Narva culture

Pit–Comb Ware culture

Pitted Ware culture

Bell Beaker culture

Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture

Abashevo culture

Sintashta culture

Mierzanowice culture

Unetice culture

Nordic Bronze Age

Komarov culture

Category:Indo-European

Category:Indo-European

File:Indo-European migrations.gif

Indo-European languages

List of Indo-European languages

Albanoid

Albanian language

Armenian language

Balto-Slavic languages

Baltic languages

Slavic languages

Celtic languages

Germanic languages

Hellenic languages

Greek language

Kurdish language

Indo-Iranian languages

Indo-Aryan languages

Iranian languages

Nuristani languages

Italic languages

Romance languages

Anatolian languages

Tocharian languages

Paleo-Balkan languages

Dacian language

Illyrian language

Liburnian language

Messapic language

Mysian language

Paeonian language

Phrygian language

Thracian language

Proto-Indo-European language

Proto-Indo-European phonology

Indo-European sound laws

Proto-Indo-European accent

Indo-European ablaut

Paleo-Balkan languages

Daco-Thracian

Graeco-Albanian

Graeco-Armenian

Graeco-Aryan

Graeco-Phrygian

Indo-Hittite

Italo-Celtic

Thraco-Illyrian

Indo-European vocabulary

Proto-Indo-European root

Proto-Indo-European verbs

Proto-Indo-European nominals

Proto-Indo-European pronouns

Proto-Indo-European numerals

Proto-Indo-European particles

Proto-Albanian language

Proto-Anatolian language

Proto-Armenian language

Proto-Germanic language

Proto-Norse language

Proto-Italo-Celtic language

Proto-Celtic language

Proto-Italic language

Proto-Greek language

Proto-Balto-Slavic language

Proto-Slavic language

Proto-Baltic language

Proto-Indo-Iranian language

Proto-Iranian language

Hittite inscriptions

Hieroglyphic Luwian

Linear B

Rigveda

Avesta

Homer

Behistun Inscription

Gaulish#Corpus

Old Latin#Corpus

Runic inscriptions

Ogham

Gothic Bible

Bible translations into Armenian

Tocharian script

Old Irish#Sources

Proto-Indo-European homeland

Proto-Indo-Europeans

Proto-Indo-European society

Proto-Indo-European mythology

Kurgan hypothesis

Indo-European migrations

Eurasian nomads

Anatolian hypothesis

Armenian hypothesis

Beech argument

Indigenous Aryanism

Proto-Indo-European homeland#Baltic homeland

Paleolithic continuity theory

Chalcolithic

Domestication of the horse

Kurgan

Kurgan stelae

Kurgan culture

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language

Bug–Dniester culture

Sredny Stog culture

Dnieper–Donets culture

Samara culture

Khvalynsk culture

Yamnaya culture

Mikhaylovka culture

Novotitarovskaya culture

Maykop culture

Afanasievo culture

Usatovo culture

Cernavodă culture

Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

Baden culture

Middle Dnieper culture

Bronze Age

Chariot

Yamnaya culture

Catacomb culture

Multi-cordoned ware culture

Poltavka culture

Srubnaya culture

Abashevo culture

Andronovo culture

Sintashta culture

Globular Amphora culture

Bell Beaker culture

Únětice culture

Trzciniec culture

Nordic Bronze Age

Terramare culture

Tumulus culture

Urnfield culture

Lusatian culture

Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex

Yaz culture

Gandhara grave culture

Iron Age

Chernoles culture

Thraco-Cimmerian

Hallstatt culture

Jastorf culture

Colchian culture

Painted Grey Ware culture

Northern Black Polished Ware

Bronze Age

Anatolian peoples

Hittites

Armenians

Mycenaean Greece

Indo-Iranians

Iron Age

Indo-Aryan peoples

Iranian peoples

Wusun

Yuezhi

Celts

Gauls

Celtiberians

Insular Celts

Cimmerians

Greeks

Italic peoples

Germanic peoples

Paleo-Balkan languages

Iron Age Anatolia

Thracians

Dacians

Illyrians

Paeonians

Phrygians

Scythians

Middle Ages

Tocharians

Origin of the Albanians

Balts

Early Slavs

Norsemen

North Germanic peoples

Middle Ages

Medieval India

Greater Iran

Proto-Indo-European mythology

Proto-Indo-Iranian paganism

Ancient Iranian religion

Hittite mythology and religion

Indian religions

Historical Vedic religion

Hinduism

Buddhism

Jainism

Sikhism

Iranian religions

Persian mythology

Zoroastrianism

Kurdish mythology

Yazidis

Yarsanism

Scythian religion

Ossetian mythology

Armenian mythology

European paganism

Paleo-Balkan mythology

Albanian folk beliefs

Illyrian religion

Thracian religion

Dacian religion

Ancient Greek religion

Religion in ancient Rome

Ancient Celtic religion

Irish mythology

Scottish mythology

Breton mythology

Welsh mythology

Cornish mythology

Germanic paganism

Anglo-Saxon paganism

Continental Germanic mythology

Old Norse religion

Baltic mythology

Latvian mythology

Lithuanian mythology

Slavic paganism

Fire worship#Indo-European religions

Horse sacrifice

Sati (practice)

Winter solstice

Yule

Indo-European studies

Marija Gimbutas

J. P. Mallory

Copenhagen Studies in Indo-European

Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture

The Horse, the Wheel, and Language

Journal of Indo-European Studies

Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

Indo-European Etymological Dictionary

Template:Indo-European topics

Template talk:Indo-European topics

Special:EditPage/Template:Indo-European topics

Archaeological horizon

Europe

Neolithic Europe

Chalcolithic Europe

Bronze Age Europe

Contact zone

Yamnaya culture

Rhine

Volga River

Northern Europe

Central Europe

Eastern Europe

Autosomal

Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup

Indo-European languages

German language

Pottery

Tumulus

Battle Axe culture

Battle axe

File:Distribution of archaeological cultures in Europe and Caucasus before and after 3000 BCE.png

Rhine

Volga River

Germany

Netherlands

Denmark

Poland

Lithuania

Latvia

Estonia

Belarus

Czech Republic

Austria

Hungary

Slovakia

Switzerland

Romania

Ukraine

Russia

Norway

Sweden

Finland

Rhine

Volga River

Bell Beaker culture

Elbe

Indo-European migrations

File:Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte Berlin 031.jpg

Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte (Berlin)

Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

Yamnaya culture

Updating...x

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.