A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Charlie Hebdo shooting | |

|---|---|

| Part of the January 2015 Île-de-France attacks | |

Police officers, emergency vehicles, and journalists at the scene two hours after the shooting | |

| Location | 10 Rue Nicolas-Appert, 11th arrondissement of Paris, France[1] |

| Coordinates | 48°51′33″N 2°22′13″E / 48.85925°N 2.37025°E |

| Date | 7 January 2015 11:30 CET (UTC+01:00) |

| Target | Charlie Hebdo employees |

Attack type | Mass shooting |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 12 |

| Injured | 11 |

| Perpetrators | Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula[4] |

| Assailants | Chérif and Saïd Kouachi |

| Motive | Islamic terrorism |

On 7 January 2015, at about 11:30 a.m. in Paris, France, the employees of the French satirical weekly magazine Charlie Hebdo were targeted in a shooting attack by two French-born Algerian Muslim brothers, Saïd Kouachi and Chérif Kouachi. Armed with rifles and other weapons, the duo murdered 12 people and injured 11 others; they identified themselves as members of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which claimed responsibility for the attack. They fled after the shooting, triggering a manhunt, and were killed by the GIGN on 9 January. The Kouachi brothers' attack was followed by several related Islamist terrorist attacks across the Île-de-France between 7 and 9 January 2015, including the Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege, in which a French-born Malian Muslim took hostages and murdered four people (all Jews) before being killed by French commandos.

In response to the shooting, France raised its Vigipirate terror alert and deployed soldiers in Île-de-France and Picardy. A major manhunt led to the discovery of the suspects, who exchanged fire with police. The brothers took hostages at a signage company in Dammartin-en-Goële on 9 January and were shot dead when they emerged from the building firing.

On 11 January, about two million people, including more than 40 world leaders, met in Paris for a rally of national unity, and 3.7 million people joined demonstrations across France. The phrase Je suis Charlie became a common slogan of support at rallies and on social media. The staff of Charlie Hebdo continued with the publication, and the following issue print ran 7.95 million copies in six languages, compared to its typical print run of 60,000 in French only.

Charlie Hebdo is a publication that has always courted controversy with satirical attacks on political and religious leaders. It published cartoons of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 2012, forcing France to temporarily close embassies and schools in more than 20 countries amid fears of reprisals. Its offices were firebombed in November 2011 after publishing a previous caricature of Muhammad on its cover.

On 16 December 2020, 14 people who were accomplices to both the Charlie Hebdo and Jewish supermarket attackers were convicted.[5] However, three of these accomplices were still not yet captured and were tried in absentia.[5]

Background

Charlie Hebdo satirical works

Charlie Hebdo (French for Charlie Weekly) is a French satirical weekly newspaper that features cartoons, reports, polemics, and jokes. The publication, irreverent and stridently non-conformist in tone, is strongly secularist, antireligious,[6] and left-wing, publishing articles that mock Catholicism, Judaism, Islam, and various other groups as local and world news unfolds. The magazine was published from 1969 to 1981 and has been again from 1992 on.[7]

Charlie Hebdo has a history of attracting controversy. In 2006, Islamic organisations under French hate speech laws unsuccessfully sued over the newspaper's re-publication of the Jyllands-Posten cartoons of Muhammad.[8][9][10] The cover of a 2011 issue retitled Charia Hebdo (French for Sharia Weekly), featured a cartoon of Muhammad, whose depiction is forbidden in most interpretations of Islam, with some Persian exceptions.[11] The newspaper's office was fire-bombed and its website hacked.[12][13] In 2012, the newspaper published a series of satirical cartoons of Muhammad, including nude caricatures;[14][15] this came days after a series of violent attacks on U.S. embassies in the Middle East, purportedly in response to the anti-Islamic film Innocence of Muslims, prompting the French government to close embassies, consulates, cultural centres, and international schools in about 20 Muslim countries.[16] Riot police surrounded the newspaper's offices to protect it against possible attacks.[15][17]

Cartoonist Stéphane "Charb" Charbonnier had been the director of publication of Charlie Hebdo since 2009.[18] Two years before the attack he stated, "We have to carry on until Islam has been rendered as banal as Catholicism."[19] In 2013, al-Qaeda added him to its most wanted list, along with three Jyllands-Posten staff members: Kurt Westergaard, Carsten Juste, and Flemming Rose.[18][20][21] Being a sport shooter, Charb applied for permit to be able to carry a firearm for self-defence. The application went unanswered.[22][23]

Numerous violent plots related to the Jyllands-Posten cartoons were discovered, primarily targeting cartoonist Westergaard, editor Rose, and the property or employees of Jyllands-Posten and other newspapers that printed the cartoons.[a] Westergaard was the subject of several attacks and planned attacks, and lived under police protection for the rest of his life. On 1 January 2010, police used guns to stop a would-be assassin in his home,[28][29] who was sentenced to nine years in prison.[b][30][31] In 2010, three men based in Norway were arrested on suspicion of planning a terror attack against Jyllands-Posten or Kurt Westergaard; two of them were convicted.[32][33] In the United States, David Headley and Tahawwur Hussain Rana were convicted in 2013 of planning terrorism against Jyllands-Posten.[34][35][36]

Secularism and blasphemy

In France, blasphemy law ceased to exist with progressive emancipation of the Republic from the Catholic Church between 1789 and 1830. In France, the principle of secularism (laïcité – the separation of church and state) was enshrined in the 1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, and in 1945 became part of the constitution. Under its terms, the government and all public administrations and services must be religion-blind and their representatives must refrain from any display of religion, but private citizens and organisations are free to practise and express the religion of their choice where and as they wish (although discrimination based on religion is prohibited).[37]

In recent years, there has been a trend towards a stricter interpretation of laïcité which would also prohibit users of certain public services from expressing their religion (e.g. the 2004 law which bans school pupils from wearing "blatant" religious symbols[38]) or ban citizens from expressing their religion in public even outside the administration and public services (e.g. a 2015 law project prohibiting the wearing of religious symbols by the employees of private crèches). This restrictive interpretation is not supported by the initial law on laïcité and is challenged by the representatives of all the major religions.[39]

Authors, humorists, cartoonists, and individuals have the right to satirise people, public actors, and religions, a right which is balanced by defamation laws. These rights and legal mechanisms were designed to protect freedom of speech from local powers, among which was the then-powerful Catholic Church in France.[40]

Though images of Muhammad are not explicitly banned by the Quran itself, prominent Islamic views have long opposed human images, especially those of prophets. Such views have gained ground among militant Islamic groups.[41][42][43] Accordingly, some Muslims take the view that the satire of Islam, of religious representatives, and above all of Islamic prophets is blasphemy in Islam punishable by death.[44] This sentiment was most famously actualized in the murder of the controversial Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh. According to the BBC, France has seen "the apparent desire of some younger, often disaffected children or grandchildren of immigrant families not to conform to western, liberal lifestyles – including traditions of religious tolerance and free speech".[45]

Attack

Charlie Hebdo headquarters

On the morning of 7 January 2015, a Wednesday, Charlie Hebdo staff were gathered at 10 Rue Nicolas-Appert in the 11th arrondissement of Paris for the weekly editorial meeting starting around 10:30. The magazine had moved into an unmarked office at this address following the 2011 firebombing of their previous premises due to the magazine's original satirization of Muhammad.[46]

Around 11:00 a.m., two armed and hooded men first burst into the wrong address at 6 Rue Nicolas-Appert, shouting "Is this Charlie Hebdo?" and threatening people. After realizing their mistake and firing a bullet through a glass door, the two men left for 10 Rue Nicolas-Appert.[47] There, they encountered cartoonist Corinne "Coco" Rey and her young daughter outside and at gunpoint, forced her to enter the passcode into the electronic door.[48]

The men sprayed the lobby with gunfire upon entering. The first victim was maintenance worker Frédéric Boisseau, who was killed as he sat at the reception desk.[49] The gunmen forced Rey at gunpoint to lead them to a second-floor office, where 15 staff members were having an editorial meeting,[50] Charlie Hebdo's first news conference of the year. Reporter Laurent Léger said they were interrupted by what they thought was the sound of a firecracker—the gunfire from the lobby—and recalled, "We still thought it was a joke. The atmosphere was still joyous."[51]

The gunmen burst into the meeting room. The shooting lasted five to ten minutes. The gunmen aimed at the journalists' heads and killed them.[52][53] During the gunfire, Rey survived uninjured by hiding under a desk, from where she witnessed the murders of Wolinski and Cabu.[54] Léger also survived by hiding under a desk as the gunmen entered.[55] Ten of the twelve people murdered were shot on the second floor, past the security door.[56]

Psychoanalyst Elsa Cayat, a French columnist of Tunisian Jewish descent, was killed.[57] Another female columnist present at the time, crime reporter Sigolène Vinson, survived; one of the shooters aimed at her but spared her, saying, "I'm not killing you because you are a woman", and telling her to convert to Islam, read the Quran and wear a veil. She said he left shouting, "Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!"[58][59][60] Other witnesses reported that the gunmen identified themselves as belonging to al-Qaeda in Yemen.[61]

Escape

An authenticated video surfaced on the Internet that shows two gunmen and a police officer, Ahmed Merabet, who is wounded and lying on a sidewalk after an exchange of gunfire. This took place near the corner of Boulevard Richard-Lenoir and Rue Moufle, 180 metres (590 ft) east of the main crime scene. One of the gunmen ran towards the policeman and shouted, "Did you want to kill us?" The policeman answered, "No, it's fine, boss", and raised his hand toward the gunman, who then murdered the policeman with a fatal shot to the head at close range.[62]

Sam Kiley, of Sky News, concluded from the video that the two gunmen were "military professionals" who likely had "combat experience", saying that the gunmen were exercising infantry tactics such as moving in "mutual support" and were firing aimed, single-round shots at the police officer. He also stated that they were using military gestures and were "familiar with their weapons" and fired "carefully aimed shots, with tight groupings".[63]

The gunmen then left the scene, shouting, "We have avenged the Prophet Muhammad. We have killed Charlie Hebdo!"[64][65][60] They escaped in a getaway car, and drove to Porte de Pantin, hijacking another car and forcing its driver out. As they drove away, they ran over a pedestrian and shot at responding police officers.[66]

It was initially believed that there were three suspects. One identified suspect turned himself in at a Charleville-Mézières police station.[67][68] Seven of the Kouachi brothers' friends and family were taken into custody.[69] Jihadist flags and Molotov cocktails were found in an abandoned getaway car, a black Citroën C3.[70]

Motive

Charlie Hebdo had attracted considerable worldwide attention for its controversial depictions of Muhammad. Hatred for Charlie Hebdo's cartoons, which made jokes about Islamic leaders as well as Muhammad, is considered to be the principal motive for the massacre. Michael Morell, former deputy director of the CIA, suggested that the motive of the attackers was "absolutely clear: trying to shut down a media organisation that lampooned the Prophet Muhammad".[71]

In March 2013, al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen, commonly known as al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), released a hit list in an edition of their English-language magazine Inspire. The list included Stéphane Charbonnier (known as Charb, the editor of Charlie Hebdo) and others whom AQAP accused of insulting Islam.[72][73] On 9 January, AQAP claimed responsibility for the attack in a speech from AQAP's top Shariah cleric Harith bin Ghazi al-Nadhari, citing the motive as "revenge for the honour" of Muhammad.[74]

Victims

Killed

- Cartoonists and journalists

- Cabu (Jean Cabut), 76, cartoonist.

- Elsa Cayat, 54, psychoanalyst and columnist – [75][76] the only woman killed in the shooting.[77]

- Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier), 47, cartoonist, columnist, and director of publication of Charlie Hebdo.

- Philippe Honoré, 73, cartoonist.

- Bernard Maris, 68, economist, editor, and columnist.[78][79]

- Mustapha Ourrad, 60, copy editor.[80]

- Tignous (Bernard Verlhac), 57, cartoonist.[81]

- Georges Wolinski, 80, cartoonist.[82]

- Others

- Frédéric Boisseau, 42, building maintenance worker for Sodexo, killed in the lobby as he came to the building on a call, the first victim of the shooting.

- Franck Brinsolaro, 49, Protection Service police officer assigned as a bodyguard for Charb.[83]

- Ahmed Merabet, 42, police officer, shot in the head as he lay wounded on the ground outside.[84]

- Michel Renaud, 69, a travel writer and festival organiser visiting Cabu.[85]

Wounded

- Philippe Lançon, journalist—shot in the face and left in a critical condition, but recovered.[86]

- Fabrice Nicolino, 59, journalist—shot in the leg.

- Riss (Laurent Sourisseau), 48, cartoonist and editorial director—shot in the shoulder.[87]

- Unidentified police officers.[50][88][89]

Uninjured and absent

Several people at the meeting were unharmed, including book designer Gérard Gaillard, who was a guest, and staff members, Sigolène Vinson,[90] Laurent Léger, and Éric Portheault.

The cartoonist Coco was coerced into letting the murderers into the building, and was not harmed.[91] Several other staff members were not in the building at the time of the shooting, including medical columnist Patrick Pelloux, cartoonists Rénald "Luz" Luzier and Catherine Meurisse and film critic Jean-Baptiste Thoret, who were late for work, cartoonist Willem, who never attends, editor-in-chief Gérard Biard and journalist Zineb El Rhazoui who were on holiday, journalist Antonio Fischetti, who was at a funeral, and comedian and columnist Mathieu Madénian. Luz arrived in time to see the gunmen escaping.[92]

Assailants

Chérif and Saïd Kouachi

Biography

Chérif and Saïd Kouachi | |

|---|---|

| Born | Chérif: 29 November 1982 Saïd: 7 September 1980 10th Ardt, Paris, France |

| Died | 9 January 2015 (aged 32 and 34) Dammartin-en-Goële, France |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Nationality | French |

| Details | |

| Date | 7–9 January 2015 |

| Location(s) | Charlie Hebdo offices |

| Target(s) | Charlie Hebdo staff |

| Killed | 12 |

| Injured | 11 |

| Weapons |

|

Police quickly identified brothers Saïd Kouachi (French: [sa.id kwaʃi]; 7 September 1980 – 9 January 2015) and Chérif Kouachi (French: [ʃeʁif]; 29 November 1982 – 9 January 2015) as the main suspects.[c] French citizens born in Paris to Algerian immigrants, the brothers were orphaned at a young age after their mother's apparent suicide and placed in a foster home in Rennes.[94] After two years, they were moved to an orphanage in Corrèze in 1994, along with a younger brother and an older sister.[98][99] The brothers moved to Paris around 2000.[100]

Chérif, also known as Abu Issen, was part of an informal gang that met in the Parc des Buttes Chaumont in Paris to perform military-style training exercises and sent would-be jihadists to fight for al-Qaeda in Iraq after the 2003 invasion.[101][102] Chérif was arrested at age 22 in January 2005 when he and another man were about to leave for Syria, at the time a gateway for jihadists wishing to fight US troops in Iraq.[103] He went to Fleury-Mérogis Prison, where he met Amedy Coulibaly.[104] In prison, they found a mentor, Djamel Beghal, who had been sentenced to ten years in prison in 2001 for his part in a plot to bomb the US embassy in Paris.[103] Beghal had once been a regular worshipper at Finsbury Park Mosque in London and a disciple of the radical preachers Abu Hamza al-Masri[105] and Abu Qatada.

Upon leaving prison, Chérif Kouachi married and got a job in a fish market on the outskirts of Paris. He became a student of Farid Benyettou, a radical Muslim preacher at the Addawa Mosque in the 19th arrondissement of Paris. Kouachi wanted to attack Jewish targets in France, but Benyettou told him that France, unlike Iraq, was not "a land of jihad".[106]

On 28 March 2008, Chérif was convicted of terrorism and sentenced to three years in prison, with 18 months suspended, for recruiting fighters for militant Islamist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's group in Iraq.[94] He said outrage at the torture of inmates by the US Army at Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib inspired him to help Iraq's insurgency.[107][108]

French judicial documents state Amedy Coulibaly and Chérif Kouachi travelled with their wives in 2010 to central France to visit Djamel Beghal. In a police interview in 2010, Coulibaly identified Chérif as a friend he had met in prison and said they saw each other frequently.[109] In 2010, the Kouachi brothers were named in connection with a plot to break out of jail with another Islamist, Smaïn Aït Ali Belkacem. Belkacem was one of those responsible for the 1995 Paris Métro and RER bombings that killed eight people.[103][110] For lack of evidence, they were not prosecuted.

From 2009 to 2010, Saïd Kouachi visited Yemen on a student visa to study at the San'a Institute for the Arabic Language. There, according to a Yemeni reporter who interviewed Saïd, he met and befriended Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the perpetrator of the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 later in 2009. Also according to the reporter, the two shared an apartment for "one or two weeks".[111]

In 2011, Saïd returned to Yemen for a number of months and trained with al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula militants.[112] According to a senior Yemeni intelligence source, he met al Qaeda preacher Anwar al-Awlaki in the southern province of Shabwa.[113] Chérif Kouachi told BFM TV that he had been funded by a network loyal to Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed by a drone strike in 2011 in Yemen.[114] According to US officials, the US provided France with intelligence in 2011 showing the brothers received training in Yemen. French authorities monitored them until the spring of 2014.[115] During the time leading to the Charlie Hebdo attack, Saïd lived with his wife and children in a block of flats in Reims. Neighbours described him as solitary.

The weapons used in the attack were supplied via the Brussels underworld. According to the Belgian press, a criminal sold Amedy Coulibaly the rocket-propelled grenade launcher and Kalashnikov rifles that the Kouachi brothers used for less than EUR €5,000 (US$5,910).[116]

In an interview between Chérif Kouachi and Igor Sahiri, one of France's BFM TV journalists, Chérif stated that "We are not killers. We are defenders of the prophet, we don't kill women. We kill no one. We defend the prophet. If someone offends the prophet then there is no problem, we can kill him. We don't kill women. We are not like you. You are the ones killing women and children in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. This isn't us. We have an honour code in Islam."[117]

After the attack: Manhunt (8 and 9 January)

A massive manhunt began immediately after the attack. One suspect left his ID card in an abandoned getaway car.[118][119] Police officers searched apartments in the Île-de-France region, in Strasbourg and in Reims.[120][121]

Police detained several people during the manhunt for the two main suspects. A third suspect voluntarily reported to a police station after hearing he was wanted and was not charged. Police described the assailants as "armed and dangerous". France raised its terror alert to its highest level and deployed soldiers in Île-de-France and Picardy regions.

At 10:30 CET on 8 January, the day following the attack, the two primary suspects were spotted in Aisne, north-east of Paris. Armed security forces, including the National Gendarmerie Intervention Group (GIGN) and the Force d'intervention de la police nationale (FIPN), were deployed to the department to search for the suspects.[122]

Later that day, the police search concentrated on the Picardy, particularly the area around Villers-Cotterêts and the village of Longpont, after the suspects robbed a petrol station near Villers-Cotterêts,[123] then reportedly abandoned their car before hiding in a forest near Longpont.[124] Searches continued into the surrounding Forêt de Retz (130 km2), one of the largest forests in France.[125]

The manhunt continued with the discovery of the two fugitive suspects early on the morning of 9 January. The Kouachis had hijacked a Peugeot 206 near the town of Crépy-en-Valois. They were chased by police cars for approximately 27 kilometres (17 miles) south down the N2 trunk road. At some point they abandoned their vehicle and an exchange of gunfire between pursuing police and the brothers took place near the commune of Dammartin-en-Goële, 35 kilometres (22 miles) northeast of Paris. Several blasts went off as well and Saïd Kouachi sustained a minor neck wound. Several others may have been injured as well but no one was killed in the gunfire. The suspects were not apprehended and escaped on foot.[126]

Dammartin-en-Goële hostage crisis, death of Chérif and Saïd (9 January)

At around 9:30 am on 9 January 2015, the Kouachi brothers fled into the office of Création Tendance Découverte, a signage production company on an industrial estate in Dammartin-en-Goële. Inside the building were owner Michel Catalano and a male employee, 26-year-old graphics designer Lilian Lepère. Catalano told Lepère to go hide in the building and remained in his office by himself.[127] Not long after, a salesman named Didier went to the printworks on business. Catalano came out with Chérif Kouachi who introduced himself as a police officer. They shook hands and Kouachi told Didier, "Leave. We don't kill civilians anyhow." These words were what caused Didier to guess that Kouachi was a terrorist and he alerted the police.[128]

The Kouachi brothers remained inside and a lengthy standoff began. Catalano re-entered the building and closed the door after Didier had left.[129] The brothers were not aggressive towards Catalano, who stated, "I didn't get the impression they were going to harm me." He made coffee for them and helped bandage the neck wound that Saïd Kouachi had sustained during the earlier gunfire. Catalano was allowed to leave after an hour.[130] Before doing so, Catalano swore three different times to the terrorists that he was alone and did not reveal Lepère's presence; ultimately the Kouachi brothers never became aware of him being there. Lepère hid inside a cardboard box and sent the Gendarmerie text messages for around three hours during the siege, providing them with "tactical elements such as location inside the premises".[131]

Given the proximity (10 km) of the siege to Charles de Gaulle Airport, two of the airport's runways were closed.[126][132] Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve called for a Gendarmerie operation to neutralise the perpetrators. An Interior Ministry spokesman announced that the Ministry wished first to "establish a dialogue" with the suspects. Officials tried to establish contact with the suspects to negotiate the safe evacuation of a school 500 metres (1,600 feet) from the siege. The Kouachi brothers did not respond to attempts at communication by the French authorities.[133]

The siege lasted for eight to nine hours, and at around 4:30 p.m. there were at least three explosions near the building. At around 5:00 pm, a GIGN team landed on the roof of the building and a helicopter landed nearby.[134] Before gendarmes could reach them, the pair ran out of the building and opened fire on gendarmes. The brothers had stated a desire to die as martyrs[135] and the siege came to an end when both Kouachi brothers were shot and killed. Lilian Lepère was rescued unharmed.[136][137] A cache of weapons, including Molotov cocktails and a rocket launcher, was found in the area.[131]

During the standoff in Dammartin-en-Goële, another jihadist named Amedy Coulibaly, who had met the brothers in prison,[138] took hostages in a kosher supermarket at Porte de Vincennes in east Paris, killing those of Jewish faith while leaving the others alive. Coulibaly was reportedly in contact with the Kouachi brothers as the sieges progressed, and told police that he would kill hostages if the brothers were harmed.[126][139] Coulibaly and the Kouachi brothers died within minutes of each other.[140]

Suspected Charlie Hebdo attack driver

The police initially identified the 18-year-old brother-in-law of Chérif Kouachi, a French Muslim student of North African descent and unknown nationality, as a third suspect in the shooting, accused of driving the getaway car.[94] He was believed to have been living in Charleville-Mézières, about 200 kilometres (120 mi) northeast of Paris near the border with Belgium.[141] He turned himself in at a Charleville-Mézières police station early in the morning on 8 January 2015.[141] The man said he was in class at the time of the shooting, and that he rarely saw Chérif Kouachi.[citation needed] Many of his classmates said that he was at school in Charleville-Mézières during the attack.[142] After detaining him for nearly 50 hours, police decided not to continue further investigations into the teenager.[143]

Peter Cherif

In December 2018, French authorities arrested Peter Cherif also known as Abu Hamza, for playing an "important role in organizing" the Charlie Hebdo attack.[144] Not only was Cherif a close friend of brothers Chérif Kouachi and Saïd Kouachi,[145] but had been on the run from French authorities since 2011. Cherif fled Paris in 2011 just before a court sentenced him to five years in prison on terrorism charges for fighting as an insurgent in Iraq.[citation needed]

2020 trial

On 2 September 2020, fourteen people went on trial in Paris charged with providing logistical support and procuring weapons for those who carried out both the Charlie Hebdo shooting and the Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege. Of the fourteen on trial Mohamed and Mehdi Belhoucine and Amedy Coulibaly's girlfriend, Hayat Boumeddiene, were tried in absentia, having fled to either Iraq or Syria in the days before the attacks took place.[146][147] In anticipation of the trial getting underway Charlie Hebdo reprinted cartoons of Muhammad with the caption: "Tout ça pour ça" ("All of that for this").[148]

The trial was scheduled to be filmed for France's official archives.[149] On 16 December 2020, the trial concluded with all fourteen defendants being convicted by a French court.[5]

Aftermath

France

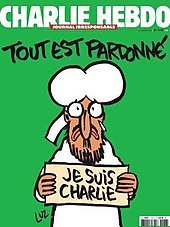

The remaining staff of Charlie Hebdo continued normal weekly publication, and the following issue print run had 7.95 million copies in six languages.[150] In contrast, its normal print run was 60,000, of which it typically sold 30,000 to 35,000 copies.[151] The cover depicts Muhammad holding a "Je suis Charlie" sign ("I am Charlie"), and is captioned "Tout est pardonné" ("All is forgiven").[152] The issue was also sold outside France.[153] The Digital Innovation Press Fund donated €250,000 to support the magazine, matching a donation by the French Press and Pluralism Fund.[154][155] The Guardian Media Group pledged £100,000 to the same cause.[156]

On the night of 8 January, police commissioner Helric Fredou, who had been investigating the attack, committed suicide in his office in Limoges while he was preparing his report shortly after meeting with the family of one of the victims. He was said to have been experiencing depression and burnout.[citation needed]

In the week after the shooting, 54 anti-Muslim incidents were reported in France. These included 21 reports of shootings, grenade throwing at mosques and other Islamic centres, an improvised explosive device attack,[157] and 33 cases of threats and insults.[d] Authorities classified these acts as right-wing terrorism.[157]

On 7 January 2016, the first anniversary of the shooting, an attempted attack occurred at a police station in the Goutte d'Or district of Paris. The assailant, a Tunisian man posing as an asylum-seeker from Iraq or Syria, wearing a fake explosive belt charged police officers with a meat cleaver while shouting "Allahu Akbar!" and was subsequently shot and killed.[164][165][166][167]

Denmark

On 14 February 2015 in Copenhagen, Denmark, a public event called "Art, blasphemy and the freedom of expression", was organised to honour victims of the attack in January against the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. A series of shootings took place that day and the following day in Copenhagen, with two people killed and five police officers wounded. The suspect, Omar Abdel Hamid El-Hussein, a recently released, radicalized prisoner, was later shot dead by police on 15 February.

United States

On 3 May 2015, two men attempted an attack on the Curtis Culwell Center in Garland, Texas. The centre was hosting an exhibit featuring cartoons depicting Muhammad. The event was presented as a response to the attack on Charlie Hebdo, and organised by the group American Freedom Defense Initiative (AFDI).[168] Both gunmen were killed by police.

Security

Following the attack, France raised Vigipirate to its highest level in history: Attack alert, an urgent terror alert which triggered the deployment of soldiers in Paris to the public transport system, media offices, places of worship and the Eiffel Tower.[169] The British Foreign Office warned its citizens about travelling to Paris. The New York City Police Department ordered extra security measures to the offices of the Consulate General of France in New York in Manhattan's Upper East Side as well as the Lycée Français de New York, which was deemed a possible target due to the proliferation of attacks in France as well as the level of hatred of the United States within the extremist community.[53] In Denmark, which was the centre of a controversy over cartoons of Muhammad in 2005, security was increased at all media outlets.[170]

Hours after the shooting, Spanish Interior Minister Jorge Fernández Díaz said that Spain's anti-terrorist security level had been upgraded and that the country was sharing information with France in relation to the attacks. Spain increased security in public places such as railway stations and increased the police presence on streets throughout the country's cities.[171]

The British Transport Police confirmed on 8 January that they would establish new armed patrols in and around St Pancras International railway station in London, following reports that the suspects were moving north towards Eurostar stations. They confirmed that the extra patrols were for the reassurance of the public and to maintain visibility and that there were no credible reports yet of the suspects heading towards St Pancras.[172]

In Belgium, the staff of P-Magazine were given police protection, although there were no specific threats. P-Magazine had previously published a cartoon of Muhammad drawn by the Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard.[173]

Demonstrations

7 January

On the evening of the day of the attack, demonstrations against the attack were held at the Place de la République in Paris[174] and in other cities including Toulouse,[175] Nice, Lyon, Marseille and Rennes.

The phrase Je suis Charlie (French for "I am Charlie") came to be a common worldwide sign of solidarity against the attacks.[176] Many demonstrators used the slogan to express solidarity with the magazine. It appeared on printed and hand-made placards, and was displayed on mobile phones at vigils, and on many websites, particularly media sites such as Le Monde. The hashtag #jesuischarlie quickly trended at the top of Twitter hashtags worldwide following the attack.[177]

Not long after the attack, it is estimated that around 35,000 people gathered in Paris holding "Je suis Charlie" signs. 15,000 people also gathered in Lyon and Rennes.[178] 10,000 people gathered in Nice and Toulouse; 7,000 in Marseille; and 5,000 each in Nantes, Grenoble and Bordeaux. Thousands also gathered in Nantes at the Place Royale.[179] More than 100,000 people in total gathered within France to partake in these demonstrations the evening of 7 January.[180]

- Protests in France

-

Demonstrators gather at the Place de la République in Paris on the night of the attack

-

Memorial for Ahmed Merabet

-

Demonstrators in Bordeaux

-

Tribute to Charlie Hebdo in Strasbourg

-

Tributes to the victims in Toulouse

Similar demonstrations and candle vigils spread to other cities outside France as well, including Amsterdam,[181] Brussels, Barcelona,[182] Ljubljana,[183] Berlin, Copenhagen, London and Washington, D.C.[184] Around 2,000 demonstrators gathered in London's Trafalgar Square and sang La Marseillaise, the French national anthem.[185][186] In Brussels, two vigils have been held thus far, one immediately at the city's French consulate and a second one at Place du Luxembourg. Many flags around the city were at half-mast on 8 January.[187] In Luxembourg, a demonstration was held in the Place de la Constitution.[188]

A crowd gathered on the evening of 7 January, at Union Square in Manhattan, New York City. French ambassador to the United Nations François Delattre was present; the crowd lit candles, held signs, and sang the French national anthem.[189] Several hundred people also showed up outside of the French consulate in San Francisco with "Je suis Charlie" signs to show their solidarity.[190] In downtown Seattle, another vigil was held where people gathered around a French flag laid out with candles lit around it. They prayed for the victims and held "Je suis Charlie" signs.[191] In Argentina, a large demonstration was held to denounce the attacks and show support for the victims outside the French embassy in the Buenos Aires.[192]

More vigils and gatherings were held in Canada to show support to France and condemn terrorism. Many cities had notable "Je suis Charlie" gatherings, including Calgary, Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto.[193] In Calgary, there was a strong anti-terrorism sentiment. "We're against terrorism and want to show them that they won't win the battle. It's horrible everything that happened, but they won't win," commented one demonstrator. "It's not only against the French journalists or the French people, it's against freedom – everyone, all over the world, is concerned at what's happening."[194] In Montreal, despite a temperature of −21 °C (−6 °F), over 1,000 people gathered chanting "Liberty!" and "Charlie!" outside of the city's French Consulate. Montreal Mayor Denis Coderre was among the gatherers and proclaimed, "Today, we are all French!" He confirmed the city's full support for the people of France and called for strong support regarding freedom, stating that "We have a duty to protect our freedom of expression. We have the right to say what we have to say."[195][196]

8 January

By 8 January, vigils had spread to Australia, with thousands holding "Je suis Charlie" signs. In Sydney, people gathered at Martin Place – the location of a siege less than a month earlier – and in Hyde Park dressed in white clothing as a form of respect. Flags were at half-mast at the city's French consulate where mourners left bouquets.[197] A vigil was held at Federation Square in Melbourne with an emphasis on togetherness. French consul Patrick Kedemos described the gathering in Perth as "a spontaneous, grassroots event". He added, "We are far away but our hearts today with our families and friends in France. It an attack on the liberty of expression, journalists that were prominent in France, and at the same time it's an attack or a perceived attack on our culture."[198]

On 8 January over 100 demonstrations were held from 18:00 in the Netherlands at the time of the silent march in Paris, after a call to do so from the mayors of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht, and other cities. Many Dutch government members joined the demonstrations.[199][200]

- Protests around the world

-

Brisbane, Australia

-

Berlin, Germany

-

Luxembourg, 8 January 2015

-

Bologna, Italy

-

Daley Plaza, Chicago, U.S.

-

French Embassy, Moscow, Russia

-

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Charlie_Hebdo_shooting

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

File:Charlie-Hebdo-2015-11.JPG

Rue Nicolas-Appert

11th arrondissement of Paris

Geographic coordinate system

Central European Time

UTC+01:00

Charlie Hebdo

Mass shooting

Zastava M70

Škorpion vz. 61

M80 Zolja

TT pistol

Pump action

Shotgun

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

Islamic terrorism

Paris

Charlie Hebdo

Islam in Algeria

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

GIGN

January 2015 Île-de-France attacks

Île-de-France

Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege

Islam in Mali

Jews

Vigipirate

Picardy

Manhunt (law enforcement)

Dammartin-en-Goële

Republican marches

Je suis Charlie

Charlie Hebdo issue No. 1178

Prophets and messengers in Islam

Muhammad

Trial in absentia

Charlie Hebdo

List of satirical magazines

Polemic

Laïcité

Antireligion

Left-wing politics

Catholicism

Judaism

Islam

Hate speech laws in France

Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

Charia Hebdo

Sharia

Muhammad

Depictions of Muhammad

Persian people

Hacker (computer security)

Reactions to Innocence of Muslims

Innocence of Muslims

Government of France

Muslim world

Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité

Charb

Al-Qaeda

Most wanted list

Kurt Westergaard

Carsten Juste

Flemming Rose

Concealed carry

David Headley

Tahawwur Hussain Rana

Islam and blasphemy

Blasphemy law#France

Secularism

Separation of church and state

1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and the State

Freedom of speech

Roman Catholicism in France

Quran

Aniconism in Islam

Islam

Islam and blasphemy

Theo van Gogh (film director)

BBC

Rue Nicolas-Appert

11th arrondissement of Paris

Coco (cartoonist)

Georges Wolinski

Cabu

Elsa Cayat

Sigolène Vinson

Conversion to Islam

Islam

Quran

Veil

Takbir#Usage by extremists and terrorists

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

File:Charlie-Hebdo-2015-1.JPG

Boulevard Richard-Lenoir

Sky News

Muhammad

Porte de Pantin (Paris Métro)

Charleville-Mézières

Molotov cocktail

Citroën C3

Depictions of Muhammad

Muhammad

Michael Morell

Central Intelligence Agency

Al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula

Inspire (magazine)

Harith bin Ghazi al-Nadhari

File:Plaque Charlie Hebdo.jpg

Cabu

Cartoonist

Elsa Cayat

Charb

Philippe Honoré (cartoonist)

Bernard Maris

Mustapha Ourrad

Tignous

Georges Wolinski

Sodexo

Service de la protection

File:CABU AOUT 2012.jpg

Cabu

File:Elsa Cayat.jpg

Elsa Cayat

File:2011-11-02 Incendie à Charlie Hebdo - Charb - 06.jpg

Charb

File:Philippe Honoré, dessinateur de Charlie Hebdo (crop).jpg

Philippe Honoré (cartoonist)

File:Tignous 20080318 Salon du livre 1.jpg

Tignous

File:Salon du livre de Paris 2011 - Georges Wolinski - 007.JPG

Georges Wolinski

Philippe Lançon

Fabrice Nicolino

Riss (cartoonist)

Sigolène Vinson

Coco (cartoonist)

Patrick Pelloux

Luz (cartoonist)

Catherine Meurisse

Bernard Willem Holtrop

Editor-in-chief

Gérard Biard

Zineb El Rhazoui

Mathieu Madénian

File:Chérif Kouachi.jpg

File:Saïd Kouachi.jpg

10th arrondissement of Paris

Dammartin-en-Goële

Ballistic trauma

Charlie Hebdo

Zastava M70

Škorpion vz. 61

Pump action shotgun

TT pistol

Help:IPA/French

Help:IPA/French

Rennes

Corrèze

Parc des Buttes Chaumont

Jihadism

Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn

2003 invasion of Iraq

Syria

Fleury-Mérogis Prison

Amedy Coulibaly

Djamel Beghal

Paris embassy attack plot

Finsbury Park Mosque

Abu Hamza al-Masri

Abu Qatada al-Filistini

19th arrondissement of Paris

Suspended sentence

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi

Baghdad Central Prison

Abu Ghraib

1995 Paris Métro and RER bombings

San'a Institute for the Arabic Language

Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab

Northwest Airlines Flight 253

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

Anwar al-Awlaki

Shabwah Governorate

BFM TV

Reims

Black market

Rocket-propelled grenade

Kalashnikov rifle

Euro

United States dollar

Manhunt (law enforcement)

National identity card (France)

Strasbourg

Reims

Vigipirate

French Armed Forces

Île-de-France

Picardy

Regions of France

Aisne

National Gendarmerie Intervention Group

Force d'intervention de la police nationale

Villers-Cotterêts

Longpont

Forest of Retz

List of forests in France#Picardy

Peugeot 206

Crépy-en-Valois

Dammartin-en-Goële

Dammartin-en-Goële

Charles de Gaulle Airport

Minister of the Interior (France)

Bernard Cazeneuve

GIGN

Molotov cocktail

Amedy Coulibaly

Porte de Vincennes hostage crisis

Porte de Vincennes

Charleville-Mézières

Belgium–France border

Wikipedia:Citation needed

Peter Cherif

Wikipedia:Citation needed

Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege

Amedy Coulibaly

Hayat Boumeddiene

Trial in absentia

Charlie Hebdo issue No. 1178

File:Charlie Hebdo Tout est pardonné.jpg

Je suis Charlie

Charlie Hebdo

Guardian Media Group

Suicide

Limoges

Depression (mood)

Burnout (psychology)

Wikipedia:Citation needed

Grenade

Improvised explosive device

Right-wing terrorism

January 2016 Paris police station attack

Goutte d'Or

Tunisia

Iraq

Syria

Explosive belt

2015 Copenhagen shootings

Copenhagen

Charlie Hebdo

Curtis Culwell Center attack

Curtis Culwell Center

Garland, Texas

Stop Islamization of America

Vigipirate

Eiffel Tower

British Foreign Office

New York City Police Department

Consulate General of France in New York

Manhattan

Upper East Side

Lycée Français de New York

Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

Ministry of the Interior (Spain)

Jorge Fernández Díaz

British Transport Police

St Pancras International railway station

Eurostar

P-Magazine

Kurt Westergaard

Je suis Charlie

Place de la République

Toulouse

Nice

Lyon

Marseille

Rennes

Je suis Charlie

Le Monde

Hashtag

Nantes

File:Place de la République, 18h50, une foule silencieuse.jpg

Place de la République

File:Lieu assassinat du policier Ahmed Merabet.JPG

File:Rassemblement de soutien à Charlie Hebdo - 7 janvier 2015 - Bordeaux 04.JPG

Bordeaux

File:Je suis Charlie Strasbourg 7 janvier 2015.jpg

Strasbourg

File:Toulouse est Charlie - 5450.jpg

Toulouse

Amsterdam

Brussels

Barcelona

Ljubljana

Copenhagen

Washington, D.C.

Trafalgar Square

La Marseillaise

National anthem

Place du Luxembourg

Half-mast

Luxembourg

Union Square, Manhattan

Manhattan

François Delattre

San Francisco

Seattle

List of diplomatic missions in Argentina#Embassies

Calgary

Montreal

Ottawa

Denis Coderre

Martin Place

2014 Sydney hostage crisis

Hyde Park, Sydney

Federation Square

Melbourne

Updating...x

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.