A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

G. K. Chesterton | |

|---|---|

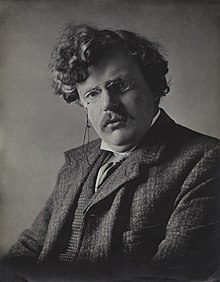

Chesterton in 1909 | |

| Born | Gilbert Keith Chesterton 29 May 1874 Kensington, London, England |

| Died | 14 June 1936 (aged 62) Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Resting place | Roman Catholic Cemetery, Beaconsfield |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | University College London |

| Period | 1900–1936 |

| Genre | Essays, fantasy, Christian apologetics, Catholic apologetics, mystery, poetry |

| Literary movement | Catholic literary revival[1] |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Gilbert Keith Chesterton KC*SG (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English author, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic.[2]

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown,[3] and wrote on apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man.[4][5] Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an orthodox Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting from high church Anglicanism. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Henry Newman and John Ruskin.[6]

He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox".[7] Of his writing style, Time observed: "Whenever possible, Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out."[4] His writings were an influence on Jorge Luis Borges, who compared his work with that of Edgar Allan Poe.[8]

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

Biography

Early life

Chesterton was born in Campden Hill in Kensington, London, on 29 May 1874. His father was Edward Chesterton, an estate agent, and his mother was Marie Louise, née Grosjean, of Swiss-French origin.[9][10][11] Chesterton was baptised at the age of one month into the Church of England,[12] though his family themselves were irregularly practising Unitarians.[13] According to his autobiography, as a young man he became fascinated with the occult and, along with his brother Cecil, experimented with Ouija boards.[14] He was educated at St Paul's School, then attended the Slade School of Art to become an illustrator. The Slade is a department of University College London, where Chesterton also took classes in literature, but he did not complete a degree in either subject. He married Frances Blogg in 1901; the marriage lasted the rest of his life. Chesterton credited Frances with leading him back to Anglicanism, though he later considered Anglicanism to be a "pale imitation". He entered in full communion with the Catholic Church in 1922.[15] The couple were unable to have children.[16][17]

A friend from schooldays was Edmund Clerihew Bentley, inventor of the clerihew, a whimsical four-line biographical poem. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend's first published collection of poetry, Biography for Beginners (1905), which popularised the clerihew form. He became godfather to Bentley's son, Nicolas, and opened his novel The Man Who Was Thursday with a poem written to Bentley.[citation needed]

Career

In September 1895, Chesterton began working for the London publisher George Redway, where he remained for just over a year.[18] In October 1896, he moved to the publishing house T. Fisher Unwin,[18] where he remained until 1902. During this period he also undertook his first journalistic work, as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1902, The Daily News gave him a weekly opinion column, followed in 1905 by a weekly column in The Illustrated London News, for which he continued to write for the next thirty years.

Early on Chesterton showed a great interest in and talent for art. He had planned to become an artist, and his writing shows a vision that clothed abstract ideas in concrete and memorable images. Father Brown is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition, repentance and reconciliation. For example, in the story "The Flying Stars", Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: "There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don't fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good, but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I've known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime."[19]

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as George Bernard Shaw,[20] H. G. Wells, Bertrand Russell and Clarence Darrow.[21][22] According to his autobiography, he and Shaw played cowboys in a silent film that was never released.[23] On 7 January 1914 Chesterton (along with his brother Cecil and future sister-in-law Ada) took part in the mock-trial of John Jasper for the murder of Edwin Drood. Chesterton was Judge and George Bernard Shaw played the role of foreman of the jury.[24]

Chesterton was a large man, standing 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) tall and weighing around 20 stone 6 pounds (130 kg; 286 lb). His girth gave rise to an anecdote during the First World War, when a lady in London asked why he was not "out at the Front"; he replied, "If you go round to the side, you will see that I am."[25] On another occasion he remarked to his friend George Bernard Shaw, "To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England." Shaw retorted, "To look at you, anyone would think you had caused it."[26] P. G. Wodehouse once described a very loud crash as "a sound like G. K. Chesterton falling onto a sheet of tin".[27] Chesterton usually wore a cape and a crumpled hat, with a swordstick in hand, and a cigar hanging out of his mouth. He had a tendency to forget where he was supposed to be going and miss the train that was supposed to take him there. It is reported that on several occasions he sent a telegram to his wife Frances from an incorrect location, writing such things as "Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?" to which she would reply, "Home".[28] Chesterton himself told this story, omitting, however, his wife's alleged reply, in his autobiography.[29]

In 1931, the BBC invited Chesterton to give a series of radio talks. He accepted, tentatively at first. He was allowed (and encouraged) to improvise on the scripts. This allowed his talks to maintain an intimate character, as did the decision to allow his wife and secretary to sit with him during his broadcasts.[30] The talks were very popular. A BBC official remarked, after Chesterton's death, that "in another year or so, he would have become the dominating voice from Broadcasting House."[31] Chesterton was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1935.[32]

Chesterton was part of the Detection Club, a society of British mystery authors founded by Anthony Berkeley in 1928. He was elected as the first president and served from 1930 to 1936 until he was succeeded by E. C. Bentley.[33]

Chesterton was one of the dominating figures of the London literary scene in the early 20th century.

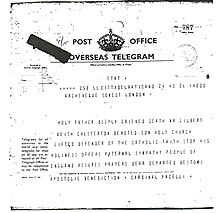

Death

Chesterton died of congestive heart failure on 14 June 1936, aged 62, at his home in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. His last words were a greeting of good morning spoken to his wife Frances. The sermon at Chesterton's Requiem Mass in Westminster Cathedral, London, was delivered by Ronald Knox on 27 June 1936. Knox said, "All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton's influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton."[34] He is buried in Beaconsfield in the Catholic Cemetery. Chesterton's estate was probated at £28,389, equivalent to £2,436,459 in 2023.[35]

Near the end of Chesterton's life, Pope Pius XI invested him as Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great (KC*SG).[31] The Chesterton Society has proposed that he be beatified.[36]

Writing

Chesterton wrote around 80 books, several hundred poems, some 200 short stories, 4,000 essays (mostly newspaper columns), and several plays. He was a literary and social critic, historian, playwright, novelist, and Catholic theologian[37][38] and apologist, debater, and mystery writer. He was a columnist for the Daily News, The Illustrated London News, and his own paper, G. K.'s Weekly; he also wrote articles for the Encyclopædia Britannica, including the entry on Charles Dickens and part of the entry on Humour in the 14th edition (1929). His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown,[3] who appeared only in short stories, while The Man Who Was Thursday is arguably his best-known novel. He was a convinced Christian long before he was received into the Catholic Church, and Christian themes and symbolism appear in much of his writing. In the United States, his writings on distributism were popularised through The American Review, published by Seward Collins in New York.

Of his nonfiction, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906) has received some of the broadest-based praise. According to Ian Ker (The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961, 2003), "In Chesterton's eyes Dickens belongs to Merry, not Puritan, England"; Ker treats Chesterton's thought in chapter 4 of that book as largely growing out of his true appreciation of Dickens, a somewhat shop-soiled property in the view of other literary opinions of the time. The biography was largely responsible for creating a popular revival for Dickens's work as well as a serious reconsideration of Dickens by scholars.[39]

Chesterton's writings consistently displayed wit and a sense of humour. He employed paradox, while making serious comments on the world, government, politics, economics, philosophy, theology and many other topics.[40][41]

T. S. Eliot summed up his work as follows:

He was importantly and consistently on the side of the angels. Behind the Johnsonian fancy dress, so reassuring to the British public, he concealed the most serious and revolutionary designs—concealing them by exposure ... Chesterton's social and economic ideas ... were fundamentally Christian and Catholic. He did more, I think, than any man of his time—and was able to do more than anyone else, because of his particular background, development and abilities as a public performer—to maintain the existence of the important minority in the modern world. He leaves behind a permanent claim upon our loyalty, to see that the work that he did in his time is continued in ours.[42]

Eliot commented further that "His poetry was first-rate journalistic balladry, and I do not suppose that he took it more seriously than it deserved. He reached a high imaginative level with The Napoleon of Notting Hill, and higher with The Man Who Was Thursday, romances in which he turned the Stevensonian fantasy to more serious purpose. His book on Dickens seems to me the best essay on that author that has ever been written. Some of his essays can be read again and again; though of his essay-writing as a whole, one can only say that it is remarkable to have maintained such a high average with so large an output."[42]

In 2022, a three-volume bibliography of Chesterton was published, listing 9,000 contributions he made to newspapers, magazines, and journals, as well as 200 books and 3,000 articles about him.[43]

Contemporaries

"Chesterbelloc"

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayist Hilaire Belloc.[44][45] George Bernard Shaw coined the name "Chesterbelloc"[46] for their partnership,[47] and this stuck. Though they were very different men, they shared many beliefs;[48] in 1922, Chesterton joined Belloc in the Catholic faith, and both voiced criticisms of capitalism and socialism.[49] They instead espoused a third way: distributism.[50] G. K.'s Weekly, which occupied much of Chesterton's energy in the last 15 years of his life, was the successor to Belloc's New Witness, taken over from Cecil Chesterton, Gilbert's brother, who died in World War I.

In his book On the Place of Gilbert Chesterton in English Letters, Belloc wrote that "Everything he wrote upon any one of the great English literary names was of the first quality. He summed up any one pen (that of Jane Austen, for instance) in exact sentences; sometimes in a single sentence, after a fashion which no one else has approached. He stood quite by himself in this department. He understood the very minds (to take the two most famous names) of Thackeray and of Dickens. He understood and presented Meredith. He understood the supremacy in Milton. He understood Pope. He understood the great Dryden. He was not swamped as nearly all his contemporaries were by Shakespeare, wherein they drown as in a vast sea – for that is what Shakespeare is. Gilbert Chesterton continued to understand the youngest and latest comers as he understood the forefathers in our great corpus of English verse and prose."[51]

Wilde

In his book Heretics, Chesterton said this of Oscar Wilde: "The same lesson was taught by the very powerful and very desolate philosophy of Oscar Wilde. It is the carpe diem religion; but the carpe diem religion is not the religion of happy people, but of very unhappy people. Great joy does not gather the rosebuds while it may; its eyes are fixed on the immortal rose which Dante saw."[52] More briefly, and with a closer approximation to Wilde's own style, he wrote in his 1908 book Orthodoxy concerning the necessity of making symbolic sacrifices for the gift of creation: "Oscar Wilde said that sunsets were not valued because we could not pay for sunsets. But Oscar Wilde was wrong; we can pay for sunsets. We can pay for them by not being Oscar Wilde."

Shaw

Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw were famous friends and enjoyed their arguments and discussions. Although rarely in agreement, they each maintained good will toward, and respect for, the other.[53] In his writing, Chesterton expressed himself very plainly on where they differed and why. In Heretics he writes of Shaw:

After belabouring a great many people for a great many years for being unprogressive, Mr Shaw has discovered, with characteristic sense, that it is very doubtful whether any existing human being with two legs can be progressive at all. Having come to doubt whether humanity can be combined with progress, most people, easily pleased, would have elected to abandon progress and remain with humanity. Mr Shaw, not being easily pleased, decides to throw over humanity with all its limitations and go in for progress for its own sake. If man, as we know him, is incapable of the philosophy of progress, Mr Shaw asks, not for a new kind of philosophy, but for a new kind of man. It is rather as if a nurse had tried a rather bitter food for some years on a baby, and on discovering that it was not suitable, should not throw away the food and ask for a new food, but throw the baby out of window, and ask for a new baby.[54]

Views

Advocacy of Catholicism

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

Chesterton's views, in contrast to Shaw and others, became increasingly focused towards the Church. In Orthodoxy he wrote: "The worship of will is the negation of will ... If Mr Bernard Shaw comes up to me and says, 'Will something', that is tantamount to saying, 'I do not mind what you will', and that is tantamount to saying, 'I have no will in the matter.' You cannot admire will in general, because the essence of will is that it is particular."[55]

Chesterton's The Everlasting Man contributed to C. S. Lewis's conversion to Christianity. In a letter to Sheldon Vanauken (14 December 1950),[56] Lewis called the book "the best popular apologetic I know",[57] and to Rhonda Bodle he wrote (31 December 1947)[58] "the best popular defence of the full Christian position I know is G. K. Chesterton's The Everlasting Man". The book was also cited in a list of 10 books that "most shaped his vocational attitude and philosophy of life".[59]

Chesterton's hymn "O God of Earth and Altar" was printed in The Commonwealth and then included in The English Hymnal in 1906.[60] Several lines of the hymn appear in the beginning of the song "Revelations" by the British heavy metal band Iron Maiden on their 1983 album Piece of Mind.[61] Lead singer Bruce Dickinson in an interview stated "I have a fondness for hymns. I love some of the ritual, the beautiful words, Jerusalem and there was another one, with words by G. K. Chesterton O God of Earth and Altar – very fire and brimstone: 'Bow down and hear our cry'. I used that for an Iron Maiden song, "Revelations". In my strange and clumsy way I was trying to say look it's all the same stuff."[62]

Étienne Gilson praised Chesterton's book on Thomas Aquinas: "I consider it as being, without possible comparison, the best book ever written on Saint Thomas ... the few readers who have spent twenty or thirty years in studying St. Thomas Aquinas, and who, perhaps, have themselves published two or three volumes on the subject, cannot fail to perceive that the so-called 'wit' of Chesterton has put their scholarship to shame."[63]

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, the author of 70 books, identified Chesterton as the stylist who had the greatest impact on his own writing, stating in his autobiography Treasure in Clay, "the greatest influence in writing was G. K. Chesterton who never used a useless word, who saw the value of a paradox, and avoided what was trite."[64] Chesterton wrote the introduction to Sheen's book God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy; A Critical Study in the Light of the Philosophy of Saint Thomas.[65]