A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

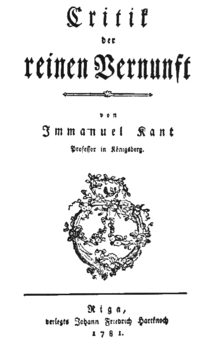

Title page of the 1781 edition | |

| Author | Immanuel Kant |

|---|---|

| Original title | Critik a der reinen Vernunft |

| Translator | see below |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Metaphysics |

| Published | 1781 |

| Pages | 856 (first German edition)[1] |

| a Kritik in modern German. | |

| Part of a series on |

| Immanuel Kant |

|---|

|

|

Category • |

The Critique of Pure Reason (German: Kritik der reinen Vernunft; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was followed by his Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and Critique of Judgment (1790). In the preface to the first edition, Kant explains that by a "critique of pure reason" he means a critique "of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of all knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience" and that he aims to reach a decision about "the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics". The term "critique" is understood to mean a systematic analysis in this context, rather than the colloquial sense of the term.

Kant builds on the work of empiricist philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume, as well as rationalist philosophers such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Christian Wolff. He expounds new ideas on the nature of space and time, and tries to provide solutions to the skepticism of Hume regarding knowledge of the relation of cause and effect and that of René Descartes regarding knowledge of the external world. This is argued through the transcendental idealism of objects (as appearance) and their form of appearance. Kant regards the former "as mere representations and not as things in themselves", and the latter as "only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves". This grants the possibility of a priori knowledge, since objects as appearance "must conform to our cognition...which is to establish something about objects before they are given to us." Knowledge independent of experience Kant calls "a priori" knowledge, while knowledge obtained through experience is termed "a posteriori".[2] According to Kant, a proposition is a priori if it is necessary and universal. A proposition is necessary if it is not false in any case and so cannot be rejected; rejection is contradiction. A proposition is universal if it is true in all cases, and so does not admit of any exceptions. Knowledge gained a posteriori through the senses, Kant argues, never imparts absolute necessity and universality, because it is possible that we might encounter an exception.[3]

Kant further elaborates on the distinction between "analytic" and "synthetic" judgments.[4] A proposition is analytic if the content of the predicate-concept of the proposition is already contained within the subject-concept of that proposition.[5] For example, Kant considers the proposition "All bodies are extended" analytic, since the predicate-concept ('extended') is already contained within—or "thought in"—the subject-concept of the sentence ('body'). The distinctive character of analytic judgments was therefore that they can be known to be true simply by an analysis of the concepts contained in them; they are true by definition. In synthetic propositions, on the other hand, the predicate-concept is not already contained within the subject-concept. For example, Kant considers the proposition "All bodies are heavy" synthetic, since the concept 'body' does not already contain within it the concept 'weight'.[6] Synthetic judgments therefore add something to a concept, whereas analytic judgments only explain what is already contained in the concept.

Prior to Kant, it was thought that all a priori knowledge must be analytic. Kant, however, argues that our knowledge of mathematics, of the first principles of natural science, and of metaphysics, is both a priori and synthetic. The peculiar nature of this knowledge cries out for explanation. The central problem of the Critique is therefore to answer the question: "How are synthetic a priori judgments possible?"[7] It is a "matter of life and death" to metaphysics and to human reason, Kant argues, that the grounds of this kind of knowledge be explained.[7]

Though it received little attention when it was first published, the Critique later attracted attacks from both empiricist and rationalist critics, and became a source of controversy. It has exerted an enduring influence on Western philosophy, and helped bring about the development of German idealism. The book is considered a culmination of several centuries of early modern philosophy and an inauguration of modern philosophy.

Background

Early rationalism

Before Kant, it was generally held that truths of reason must be analytic, meaning that what is stated in the predicate must already be present in the subject (e.g., "An intelligent man is intelligent" or "An intelligent man is a man").[8] In either case, the judgment is analytic because it is ascertained by analyzing the subject. It was thought that all truths of reason, or necessary truths, are of this kind: that in all of them there is a predicate that is only part of the subject of which it is asserted.[8] If this were so, attempting to deny anything that could be known a priori (e.g., "An intelligent man is not intelligent" or "An intelligent man is not a man") would involve a contradiction. It was therefore thought that the law of contradiction is sufficient to establish all a priori knowledge.[9]

David Hume at first accepted the general view of rationalism about a priori knowledge. However, upon closer examination of the subject, Hume discovered that some judgments thought to be analytic, especially those related to cause and effect, were actually synthetic (i.e., no analysis of the subject will reveal the predicate). They thus depend exclusively upon experience and are therefore a posteriori.

Kant's rejection of Hume's empiricism

Before Hume, rationalists had held that effect could be deduced from cause; Hume argued that it could not and from this inferred that nothing at all could be known a priori in relation to cause and effect. Kant, who was brought up under the auspices of rationalism, was deeply impressed by Hume's skepticism. "I freely admit that it was the remembrance of David Hume which, many years ago, first interrupted my dogmatic slumber and gave my investigations in the field of speculative philosophy a completely different direction."[10]

Kant decided to find an answer and spent at least twelve years thinking about the subject.[11] Although the Critique of Pure Reason was set down in written form in just four to five months, while Kant was also lecturing and teaching, the work is a summation of the development of Kant's philosophy throughout that twelve-year period.[12]

Kant's work was stimulated by his decision to take seriously Hume's skeptical conclusions about such basic principles as cause and effect, which had implications for Kant's grounding in rationalism. In Kant's view, Hume's skepticism rested on the premise that all ideas are presentations of sensory experience. The problem that Hume identified was that basic principles such as causality cannot be derived from sense experience only: experience shows only that one event regularly succeeds another, not that it is caused by it.

In section VI ("The General Problem of Pure Reason") of the introduction to the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant explains that Hume stopped short of considering that a synthetic judgment could be made 'a priori'. Kant's goal was to find some way to derive cause and effect without relying on empirical knowledge. Kant rejects analytical methods for this, arguing that analytic reasoning cannot tell us anything that is not already self-evident, so his goal was to find a way to demonstrate how the synthetic a priori is possible.

To accomplish this goal, Kant argued that it would be necessary to use synthetic reasoning. However, this posed a new problem: how is it possible to have synthetic knowledge that is not based on empirical observation; that is, how are synthetic a priori truths possible? This question is exceedingly important, Kant maintains, because he contends that all important metaphysical knowledge is of synthetic a priori propositions. If it is impossible to determine which synthetic a priori propositions are true, he argues, then metaphysics as a discipline is impossible.

Synthetic a priori judgments

Kant argues that there are synthetic judgments such as the connection of cause and effect (e.g., "... Every effect has a cause.") where no analysis of the subject will produce the predicate. Kant reasons that statements such as those found in geometry and Newtonian physics are synthetic judgments. Kant uses the classical example of 7 + 5 = 12. No amount of analysis will find 12 in either 7 or 5 and vice versa, since an infinite number of two numbers exist that will give the sum 12. Thus Kant arrives at the conclusion that all pure mathematics is synthetic though a priori; the number 7 is seven and the number 5 is five and the number 12 is twelve and the same principle applies to other numerals; in other words, they are universal and necessary. For Kant then, mathematics is synthetic judgment a priori. Conventional reasoning would have regarded such an equation to be analytic a priori by considering both 7 and 5 to be part of one subject being analyzed, however Kant looked upon 7 and 5 as two separate values, with the value of five being applied to that of 7 and synthetically arriving at the logical conclusion that they equal 12. This conclusion led Kant into a new problem as he wanted to establish how this could be possible: How is pure mathematics possible?[11] This also led him to inquire whether it could be possible to ground synthetic a priori knowledge for a study of metaphysics, because most of the principles of metaphysics from Plato through to Kant's immediate predecessors made assertions about the world or about God or about the soul that were not self-evident but which could not be derived from empirical observation (B18-24). For Kant, all post-Cartesian metaphysics is mistaken from its very beginning: the empiricists are mistaken because they assert that it is not possible to go beyond experience and the dogmatists are mistaken because they assert that it is possible to go beyond experience through theoretical reason.

Therefore, Kant proposes a new basis for a science of metaphysics, posing the question: how is a science of metaphysics possible, if at all? According to Kant, only practical reason, the faculty of moral consciousness, the moral law of which everyone is immediately aware, makes it possible to know things as they are.[13] This led to his most influential contribution to metaphysics: the abandonment of the quest to try to know the world as it is "in itself" independent of sense experience. He demonstrated this with a thought experiment, showing that it is not possible to meaningfully conceive of an object that exists outside of time and has no spatial components and is not structured in accordance with the categories of the understanding (Verstand), such as substance and causality. Although such an object cannot be conceived, Kant argues, there is no way of showing that such an object does not exist. Therefore, Kant says, the science of metaphysics must not attempt to reach beyond the limits of possible experience but must discuss only those limits, thus furthering the understanding of ourselves as thinking beings. The human mind is incapable of going beyond experience so as to obtain a knowledge of ultimate reality, because no direct advance can be made from pure ideas to objective existence.[14]

Kant writes: "Since, then, the receptivity of the subject, its capacity to be affected by objects, must necessarily precede all intuitions of these objects, it can readily be understood how the form of all appearances can be given prior to all actual perceptions, and so exist in the mind a priori" (A26/B42). Appearance is then, via the faculty of transcendental imagination (Einbildungskraft), grounded systematically in accordance with the categories of the understanding. Kant's metaphysical system, which focuses on the operations of cognitive faculties (Erkenntnisvermögen), places substantial limits on knowledge not founded in the forms of sensibility (Sinnlichkeit). Thus it sees the error of metaphysical systems prior to the Critique as failing to first take into consideration the limitations of the human capacity for knowledge. Transcendental imagination is described in the first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason but Kant omits it from the second edition of 1787.[15]

It is because he takes into account the role of people's cognitive faculties in structuring the known and knowable world that in the second preface to the Critique of Pure Reason Kant compares his critical philosophy to Copernicus' revolution in astronomy. Kant (Bxvi) writes:

Hitherto it has been assumed that all our knowledge must conform to objects. But all attempts to extend our knowledge of objects by establishing something in regard to them a priori, by means of concepts, have, on this assumption, ended in failure. We must therefore make trial whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge.

Just as Copernicus revolutionized astronomy by taking the position of the observer into account, Kant's critical philosophy takes into account the position of the knower of the world in general and reveals its impact on the structure of the known world. Kant's view is that in explaining the movement of celestial bodies, Copernicus rejected the idea that the movement is in the stars and accepted it as a part of the spectator. Knowledge does not depend so much on the object of knowledge as on the capacity of the knower.[16]

Transcendental idealism

Kant's transcendental idealism should be distinguished from idealistic systems such as that of George Berkeley. While Kant claimed that phenomena depend upon the conditions of sensibility, space and time, and on the synthesizing activity of the mind manifested in the rule-based structuring of perceptions into a world of objects, this thesis is not equivalent to mind-dependence in the sense of Berkeley's idealism. Kant defines transcendental idealism:

I understand by the transcendental idealism of all appearances the doctrine that they are all together to be regarded as mere representations and not things in themselves, and accordingly that time and space are only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves. To this idealism is opposed transcendental realism, which regards space and time as something given in themselves (independent of our sensibility).

— Critique of Pure Reason, A369

Kant's approach

In Kant's view, a priori intuitions and concepts provide some a priori knowledge, which also provides the framework for a posteriori knowledge. Kant also believed that causality is a conceptual organizing principle imposed upon nature, albeit nature understood as the sum of appearances that can be synthesized according to a priori concepts.

In other words, space and time are a form of perceiving and causality is a form of knowing. Both space and time and conceptual principles and processes pre-structure experience.

Things as they are "in themselves"—the thing in itself, or das Ding an sich—are unknowable. For something to become an object of knowledge, it must be experienced, and experience is structured by the mind—both space and time being the forms of intuition (Anschauung; for Kant, intuition is the process of sensing or the act of having a sensation)[17] or perception, and the unifying, structuring activity of concepts. These aspects of mind turn things-in-themselves into the world of experience. There is never passive observation or knowledge.

According to Kant, the transcendental ego—the "Transcendental Unity of Apperception"—is similarly unknowable. Kant contrasts the transcendental ego to the empirical ego, the active individual self subject to immediate introspection. One is aware that there is an "I," a subject or self that accompanies one's experience and consciousness. Since one experiences it as it manifests itself in time, which Kant proposes is a subjective form of perception, one can know it only indirectly: as object, rather than subject. It is the empirical ego that distinguishes one person from another providing each with a definite character.[18]

Contents

The Critique of Pure Reason is arranged around several basic distinctions. After the two Prefaces (the A edition Preface of 1781 and the B edition Preface of 1787) and the Introduction, the book is divided into the Doctrine of Elements and the Doctrine of Method.

Doctrine of Elements and of Method

The Doctrine of Elements sets out the a priori products of the mind, and the correct and incorrect use of these presentations. Kant further divides the Doctrine of Elements into the Transcendental Aesthetic and the Transcendental Logic, reflecting his basic distinction between sensibility and the understanding. In the "Transcendental Aesthetic" he argues that space and time are pure forms of intuition inherent in our faculty of sense. The "Transcendental Logic" is separated into the Transcendental Analytic and the Transcendental Dialectic:

- The Transcendental Analytic sets forth the appropriate uses of a priori concepts, called the categories, and other principles of the understanding, as conditions of the possibility of a science of metaphysics. The section titled the "Metaphysical Deduction" considers the origin of the categories. In the "Transcendental Deduction", Kant then shows the application of the categories to experience. Next, the "Analytic of Principles" sets out arguments for the relation of the categories to metaphysical principles. This section begins with the "Schematism", which describes how the imagination can apply pure concepts to the object given in sense perception. Next are arguments relating the a priori principles with the schematized categories.

- The Transcendental Dialectic describes the transcendental illusion behind the misuse of these principles in attempts to apply them to realms beyond sense experience. Kant’s most significant arguments are the "Paralogisms of Pure Reason", the "Antinomy of Pure Reason", and the "Ideal of Pure Reason", aimed against, respectively, traditional theories of the soul, the universe as a whole, and the existence of God. In the Appendix to the "Critique of Speculative Theology" Kant describes the role of the transcendental ideas of reason.

The Doctrine of Method contains four sections. The first section, "Discipline of Pure Reason", compares mathematical and logical methods of proof, and the second section, "Canon of Pure Reason", distinguishes theoretical from practical reason.

The divisions of the Critique of Pure Reason

Dedication

- 1. First and second Prefaces

- 2. Introduction

- 3. Transcendental Doctrine of Elements

- A. Transcendental Aesthetic

- (1) On space

- (2) On time

- B. Transcendental Logic

- (1) Transcendental Analytic

- a. Analytic of Concepts

- i. Metaphysical Deduction

- ii. Transcendental Deduction

- b. Analytic of Principles

- i. Schematism (bridging chapter)

- ii. System of Principles of Pure Understanding

- a. Axioms of Intuition

- b. Anticipations of Perception

- c. Analogies of Experience

- d. Postulates of Empirical Thought (Refutation of Idealism)

- iii. Ground of Distinction of Objects into Phenomena and Noumena

- iv. Appendix on the Amphiboly of the Concepts of Reflection

- a. Analytic of Concepts

- (2) Transcendental Dialectic: Transcendental Illusion

- a. Paralogisms of Pure Reason

- b. Antinomy of Pure Reason

- c. Ideal of Pure Reason

- d. Appendix to Critique of Speculative Theology

- (1) Transcendental Analytic

- A. Transcendental Aesthetic

- 4. Transcendental Doctrine of Method

- A. Discipline of Pure Reason

- B. Canon of Pure Reason

- C. Architectonic of Pure Reason

- D. History of Pure Reason

Table of contents

| Critique of Pure Reason[19] | |||||||||||||||

| Transcendental Doctrine of Elements | Transcendental Doctrine of Method | ||||||||||||||

| First Part: Transcendental Aesthetic | Second Part: Transcendental Logic | Discipline of Pure Reason | Canon of Pure Reason | Architectonic of Pure Reason | History of Pure Reason | ||||||||||

| Space | Time | First Division: Transcendental Analytic | Second Division: Transcendental Dialectic | ||||||||||||

| Book I: Analytic of Concepts | Book II: Analytic of Principles | Transcendental Illusion | Pure Reason as the Seat of Transcendental Illusion | ||||||||||||

| Clue to the discovery of all pure concepts of the understanding | Deductions of the pure concepts of the understanding | Schematism | System of all principles | Phenomena and Noumena | Book I: Concept of Pure Reason | Book II: Dialectical Inferences of Pure Reason | |||||||||

| Paralogisms (Psychology) | Antinomies (Cosmology) | The Ideal (Theology) | |||||||||||||

I. Transcendental Doctrine of Elements

Transcendental Aesthetic

The Transcendental Aesthetic, as the Critique notes, deals with "all principles of a priori sensibility."[20] As a further delimitation, it "constitutes the first part of the transcendental doctrine of elements, in contrast to that which contains the principles of pure thinking, and is named transcendental logic".[20] In it, what is aimed at is "pure intuition and the mere form of appearances, which is the only thing that sensibility can make available a priori."[21] It is thus an analytic of the a priori constitution of sensibility; through which "Objects are therefore given to us…, and it alone affords us intuitions."[22] This in itself is an explication of the "pure form of sensible intuitions in general is to be encountered in the mind a priori."[23] Thus, pure form or intuition is the a priori "wherein all of the manifold of appearances is intuited in certain relations."[23] from this, "a science of all principles of a priori sensibility the transcendental aesthetic."[20] The above stems from the fact that "there are two stems of human cognition…namely sensibility and understanding."[24]

This division, as the critique notes, comes "closer to the language and the sense of the ancients, among whom the division of cognition into αισθητα και νοητα is very well known."[25] An exposition on a priori intuitions is an analysis of the intentional constitution of sensibility. Since this lies a priori in the mind prior to actual object relation; "The transcendental doctrine of the senses will have to belong to the first part of the science of elements, since the conditions under which alone the objects of human cognition are given precede those under which those objects are thought".[26]

Kant distinguishes between the matter and the form of appearances. The matter is "that in the appearance that corresponds to sensation" (A20/B34). The form is "that which so determines the manifold of appearance that it allows of being ordered in certain relations" (A20/B34). Kant's revolutionary claim is that the form of appearances—which he later identifies as space and time—is a contribution made by the faculty of sensation to cognition, rather than something that exists independently of the mind. This is the thrust of Kant's doctrine of the transcendental ideality of space and time.

Kant's arguments for this conclusion are widely debated among Kant scholars. Some see the argument as based on Kant's conclusions that our representation (Vorstellung) of space and time is an a priori intuition. From here Kant is thought to argue that our representation of space and time as a priori intuitions entails that space and time are transcendentally ideal. It is undeniable from Kant's point of view that in Transcendental Philosophy, the difference of things as they appear and things as they are is a major philosophical discovery.[27] Others see the argument as based upon the question of whether synthetic a priori judgments are possible. Kant is taken to argue that the only way synthetic a priori judgments, such as those made in geometry, are possible is if space is transcendentally ideal.

In Section I (Of Space) of Transcendental Aesthetic in the Critique of Pure Reason Kant poses the following questions: What then are time and space? Are they real existences? Or, are they merely relations or determinations of things, such, however, as would equally belong to these things in themselves, though they should never become objects of intuition; or, are they such as belong only to the form of intuition, and consequently to the subjective constitution of the mind, without which these predicates of time and space could not be attached to any object?[28] The answer that space and time are real existences belongs to Newton. The answer that space and time are relations or determinations of things even when they are not being sensed belongs to Leibniz. Both answers maintain that space and time exist independently of the subject's awareness. This is exactly what Kant denies in his answer that space and time belong to the subjective constitution of the mind.[29]: 87–88

Space and time

Kant gives two expositions of space and time: metaphysical and transcendental. The metaphysical expositions of space and time are concerned with clarifying how those intuitions are known independently of experience. The transcendental expositions attempt to show how the metaphysical conclusions might be applied to enrich our understanding.

In the transcendental exposition, Kant refers back to his metaphysical exposition in order to show that the sciences would be impossible if space and time were not kinds of pure a priori intuitions. He asks the reader to take the proposition, "two straight lines can neither contain any space nor, consequently, form a figure," and then to try to derive this proposition from the concepts of a straight line and the number two. He concludes that it is simply impossible (A47-48/B65). Thus, since this information cannot be obtained from analytic reasoning, it must be obtained through synthetic reasoning, i.e., a synthesis of concepts (in this case two and straightness) with the pure (a priori) intuition of space.

In this case, however, it was not experience that furnished the third term; otherwise, the necessary and universal character of geometry would be lost. Only space, which is a pure a priori form of intuition, can make this synthetic judgment, thus it must then be a priori. If geometry does not serve this pure a priori intuition, it is empirical, and would be an experimental science, but geometry does not proceed by measurements—it proceeds by demonstrations.

Kant rests his demonstration of the priority of space on the example of geometry. He reasons that therefore if something exists, it needs to be intelligible. If someone attacked this argument, he would doubt the universality of geometry (which Kant believes no honest person would do).

The other part of the Transcendental Aesthetic argues that time is a pure a priori intuition that renders mathematics possible. Time is not a concept, since otherwise it would merely conform to formal logical analysis (and therefore, to the principle of non-contradiction). However, time makes it possible to deviate from the principle of non-contradiction: indeed, it is possible to say that A and non-A are in the same spatial location if one considers them in different times, and a sufficient alteration between states were to occur (A32/B48). Time and space cannot thus be regarded as existing in themselves. They are a priori forms of sensible intuition.

The current interpretation of Kant states that the subject inherently possesses the underlying conditions to perceive spatial and temporal presentations. The Kantian thesis claims that in order for the subject to have any experience at all, then it must be bounded by these forms of presentations (Vorstellung). Some scholars have offered this position as an example of psychological nativism, as a rebuke to some aspects of classical empiricism.

Kant's thesis concerning the transcendental ideality of space and time limits appearances to the forms of sensibility—indeed, they form the limits within which these appearances can count as sensible; and it necessarily implies that the thing-in-itself is neither limited by them nor can it take the form of an appearance within us apart from the bounds of sensibility (A48-49/B66). Yet the thing-in-itself is held by Kant to be the cause of that which appears, and this is where an apparent paradox of Kantian critique resides: while we are prohibited from absolute knowledge of the thing-in-itself, we can impute to it a cause beyond ourselves as a source of representations within us. Kant's view of space and time rejects both the space and time of Aristotelian physics and the space and time of Newtonian physics.

Transcendental Logic

In the Transcendental Logic, there is a section (titled The Refutation of Idealism) that is intended to free Kant's doctrine from any vestiges of subjective idealism, which would either doubt or deny the existence of external objects (B274-79).[30] Kant's distinction between the appearance and the thing-in-itself is not intended to imply that nothing knowable exists apart from consciousness, as with subjective idealism. Rather, it declares that knowledge is limited to phenomena as objects of a sensible intuition. In the Fourth Paralogism ("... A Paralogism is a logical fallacy"),[31] Kant further certifies his philosophy as separate from that of subjective idealism by defining his position as a transcendental idealism in accord with empirical realism (A366–80), a form of direct realism.[32][a] "The Paralogisms of Pure Reason" is the only chapter of the Dialectic that Kant rewrote for the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason. In the first edition, the Fourth Paralogism offers a defence of transcendental idealism, which Kant reconsidered and relocated in the second edition.[35]

Whereas the Transcendental Aesthetic was concerned with the role of the sensibility, the Transcendental Logic is concerned with the role of the understanding, which Kant defines as the faculty of the mind that deals with concepts.[36] Knowledge, Kant argued, contains two components: intuitions, through which an object is given to us in sensibility, and concepts, through which an object is thought in understanding. In the Transcendental Aesthetic, he attempted to show that the a priori forms of intuition were space and time, and that these forms were the conditions of all possible intuition. It should therefore be expected that we should find similar a priori concepts in the understanding, and that these pure concepts should be the conditions of all possible thought. The Logic is divided into two parts: the Transcendental Analytic and the Transcendental Dialectic. The Analytic Kant calls a "logic of truth";[37] in it he aims to discover these pure concepts which are the conditions of all thought, and are thus what makes knowledge possible. The Transcendental Dialectic Kant calls a "logic of illusion";[38] in it he aims to expose the illusions that we create when we attempt to apply reason beyond the limits of experience.

The idea of a transcendental logic is that of a logic that gives an account of the origins of our knowledge as well as its relationship to objects. Kant contrasts this with the idea of a general logic, which abstracts from the conditions under which our knowledge is acquired, and from any relation that knowledge has to objects. According to Helge Svare, "It is important to keep in mind what Kant says here about logic in general, and transcendental logic in particular, being the product of abstraction, so that we are not misled when a few pages later he emphasizes the pure, non-empirical character of the transcendental concepts or the categories."[39]

Kant's investigations in the Transcendental Logic lead him to conclude that the understanding and reason can only legitimately be applied to things as they appear phenomenally to us in experience. What things are in themselves as being noumenal, independent of our cognition, remains limited by what is known through phenomenal experience.

First Division: Transcendental Analytic

The Transcendental Analytic is divided into an Analytic of Concepts and an Analytic of Principles, as well as a third section concerned with the distinction between phenomena and noumena. In Chapter III (Of the ground of the division of all objects into phenomena and noumena) of the Transcendental Analytic, Kant generalizes the implications of the Analytic in regard to transcendent objects preparing the way for the explanation in the Transcendental Dialectic about thoughts of transcendent objects, Kant's detailed theory of the content (Inhalt) and origin of our thoughts about specific transcendent objects.[29]: 198–199 The main sections of the Analytic of Concepts are The Metaphysical Deduction and The Transcendental Deduction of the Categories. The main sections of the Analytic of Principles are the Schematism, Axioms of Intuition, Anticipations of Perception, Analogies of Experience, Postulates and follow the same recurring tabular form:

| 1. Quantity | ||

| 2. Quality |

3. Relation | |

| 4. Modality |

In the 2nd edition, these sections are followed by a section titled the Refutation of Idealism.

The metaphysical deduction

In the Metaphysical Deduction, Kant aims to derive twelve pure concepts of the understanding (which he calls "categories") from the logical forms of judgment. In the following section, he will go on to argue that these categories are conditions of all thought in general. Kant arranges the forms of judgment in a table of judgments, which he uses to guide the derivation of the table of categories.[40]

The role of the understanding is to make judgments. In judgment, the understanding employs concepts which apply to the intuitions given to us in sensibility. Judgments can take different logical forms, with each form combining concepts in different ways. Kant claims that if we can identify all of the possible logical forms of judgment, this will serve as a "clue" to the discovery of the most basic and general concepts that are employed in making such judgments, and thus that are employed in all thought.[40]

Logicians prior to Kant had concerned themselves to classify the various possible logical forms of judgment. Kant, with only minor modifications, accepts and adopts their work as correct and complete, and lays out all the logical forms of judgment in a table, reduced under four heads:

| 1. Quantity of Judgments | ||

| 2. Quality |

3. Relation | |

| 4. Modality |

Under each head, there corresponds three logical forms of judgment:[41]

1. Quantity of Judgments

|

||

2. Quality

|

3. Relation

| |

4. Modality

|

This Aristotelian method for classifying judgments is the basis for his own twelve corresponding concepts of the understanding. In deriving these concepts, he reasons roughly as follows. If we are to possess pure concepts of the understanding, they must relate to the logical forms of judgment. However, if these pure concepts are to be applied to intuition, they must have content. But the logical forms of judgment are by themselves abstract and contentless. Therefore, to determine the pure concepts of the understanding we must identify concepts which both correspond to the logical forms of judgment, and are able to play a role in organising intuition. Kant therefore attempts to extract from each of the logical forms of judgment a concept which relates to intuition. For example, corresponding to the logical form of hypothetical judgment ('If p, then q'), there corresponds the category of causality ('If one event, then another'). Kant calls these pure concepts 'categories', echoing the Aristotelian notion of a category as a concept which is not derived from any more general concept. He follows a similar method for the other eleven categories, then represents them in the following table:[42]

1. Categories of Quantity

|

||

2. Categories of Quality

|

3. Categories of Relation

| |

4. Categories of Modality

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití. Zdroj: Wikipedia.org - čítajte viac o Critique of Pure Reason

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. |