A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Democratic Republic of the Congo République démocratique du Congo (French) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Justice – Paix – Travail" (French) "Justice – Peace – Work" | |

| Anthem: Debout Congolais (French) "Arise, Congolese" | |

| Capital and largest city | Kinshasa 4°19′S 15°19′E / 4.317°S 15.317°E |

| Official languages | French |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Religion (2021)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Congolese |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| Félix Tshisekedi | |

| Sama Lukonde | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| National Assembly | |

| Formation | |

| 17 November 1879 | |

| 1 July 1885 | |

| 15 November 1908 | |

• Independence from Belgium | 30 June 1960[2] |

| 20 September 1960 | |

• Named Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1 August 1964 |

| 27 October 1971 | |

| 17 May 1997 | |

| 18 February 2006 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,345,409 km2 (905,567 sq mi) (11th) |

• Water (%) | 3.32 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 111,859,928[3] (14th) |

• Density | 46.3/km2 (119.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2012) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | low · 179th |

| Currency | Congolese franc (CDF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 to +2 (WAT and CAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +243 |

| ISO 3166 code | CD |

| Internet TLD | .cd |

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC or DR Congo), also known as Congo-Kinshasa, and known from 1971–1997 as Zaire, is a country in Central Africa. By land area, the DRC is the second-largest country in Africa and the 11th-largest in the world. With a population of around 112 million, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is the most populous officially Francophone country in the world. The national capital and largest city is Kinshasa, which is also the economic center. The country is bordered by the Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania (across Lake Tanganyika), Zambia, Angola, the Cabinda exclave of Angola and the South Atlantic Ocean.

Centered on the Congo Basin, the territory of the DRC was first inhabited by Central African foragers around 90,000 years ago and was reached by the Bantu expansion about 3,000 years ago.[7] In the west, the Kingdom of Kongo ruled around the mouth of the Congo River from the 14th to 19th centuries. In the northeast, center and east, the kingdoms of Azande, Luba, and Lunda ruled from the 16th and 17th centuries to the 19th century. King Leopold II of Belgium formally acquired rights to the Congo territory from the colonial nations of Europe in 1885 and declared the land his private property, naming it the Congo Free State. From 1885 to 1908, his colonial military forced the local population to produce rubber and committed widespread atrocities. In 1908, Leopold ceded the territory, which thus became a Belgian colony.

Congo achieved independence from Belgium on 30 June 1960 and was immediately confronted by a series of secessionist movements, the assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and the seizure of power by Mobutu Sese Seko in a 1965 coup d'état. Mobutu renamed the country Zaire in 1971 and imposed a harsh personalist dictatorship until his overthrow in 1997 by the First Congo War.[2] The country then had its name changed back and was confronted by the Second Congo War from 1998 to 2003, which resulted in the deaths of 5.4 million people.[8][9][10][11] The war ended under President Joseph Kabila who governed the country from 2001 to 2019, under whom human rights in the country remained poor and included frequent abuses such as forced disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment and restrictions on civil liberties.[12] Following the 2018 general election, in the country's first peaceful transition of power since independence, Kabila was succeeded as president by Félix Tshisekedi, who has served as president since.[13] Since 2015, the Eastern DR Congo has been the site of an ongoing military conflict in Kivu.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is extremely rich in natural resources but has suffered from political instability, a lack of infrastructure, corruption, and centuries of both commercial and colonial extraction and exploitation, followed by more than 60 years of independence, with little widespread development.[14] Besides the capital Kinshasa, the two next largest cities, Lubumbashi and Mbuji-Mayi, are both mining communities. The DRC's largest export is raw minerals, with China accepting over 50% of its exports in 2019.[2] In 2021, DR Congo's level of human development was ranked 179th out of 191 countries by the Human Development Index,[15] and is classed as a least developed country by the UN. As of 2018[update], following two decades of various civil wars and continued internal conflicts, around 600,000 Congolese refugees were still living in neighbouring countries.[16] Two million children risk starvation, and the fighting has displaced 4.5 million people.[17] The country is a member of the United Nations, Non-Aligned Movement, African Union, COMESA, Southern African Development Community, Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, and Economic Community of Central African States.

Etymology

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is named after the Congo River, which flows through the country. The Congo River is the world's deepest river and the world's third-largest river by discharge. The Comité d'études du haut Congo ("Committee for the Study of the Upper Congo"), established by King Leopold II of Belgium in 1876, and the International Association of the Congo, established by him in 1879, were also named after the river.[18]

The Congo River was named by early European sailors after the Kingdom of Kongo and its Bantu inhabitants, the Kongo people, when they encountered them in the 16th century.[19][20] The word Kongo comes from the Kongo language (also called Kikongo). According to American writer Samuel Henry Nelson: "It is probable that the word 'Kongo' itself implies a public gathering and that it is based on the root konga, 'to gather' (trans)."[21] The modern name of the Kongo people, Bakongo, was introduced in the early 20th century.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has been known in the past as, in chronological order, the Congo Free State, Belgian Congo, the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of Zaire, before returning to its current name the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[2]

At the time of independence, the country was named the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville to distinguish it from its neighbour the Republic of the Congo-Brazzaville. With the promulgation of the Luluabourg Constitution on 1 August 1964, the country became the DRC but was renamed Zaire (a past name for the Congo River) on 27 October 1971 by President Mobutu Sese Seko as part of his Authenticité initiative.[22]

The word Zaire is from a Portuguese adaptation of a Kikongo word nzadi ("river"), a truncation of nzadi o nzere ("river swallowing rivers").[23][24][25] The river was known as Zaire during the 16th and 17th centuries; Congo seems to have replaced Zaire gradually in English usage during the 18th century, and Congo is the preferred English name in 19th-century literature, although references to Zaire as the name used by the natives (i.e. derived from Portuguese usage) remained common.[26]

In 1992, the Sovereign National Conference voted to change the name of the country to the "Democratic Republic of the Congo", but the change was not made.[27] The country's name was later restored by President Laurent-Désiré Kabila when he overthrew Mobutu in 1997.[28] To distinguish it from the neighboring Republic of the Congo, it is sometimes referred to as Congo (Kinshasa), Congo-Kinshasa, or Big Congo.[29] Its name is sometimes also abbreviated as DR Congo,[30]DRC,[31] the DROC[32] and RDC (in French).[31]

History

Before Bantu expansion, the territory comprising the Democratic Republic of the Congo was home to Central Africa's oldest settled groups, the Mbuti peoples. Most of the remnants of their hunter-gatherer culture remain in the present day.

Early history

The geographical area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo was populated as early as 90,000 years ago, as shown by the 1988 discovery of the Semliki harpoon at Katanda, one of the oldest barbed harpoons ever found, believed to have been used to catch giant river catfish.[33][34]

Bantu peoples reached Central Africa at some point during the first millennium BC, then gradually started to expand southward. Their propagation was accelerated by the adoption of pastoralism and of Iron Age techniques. The people living in the south and southwest were foraging groups, whose technology involved only minimal use of metal technologies. The development of metal tools during this time period revolutionized agriculture. This led to the displacement of the hunter-gatherer groups in the east and southeast. The final wave of the Bantu expansion was complete by the 10th century, followed by the establishment of the Bantu kingdoms, whose rising populations soon made possible intricate local, regional and foreign commercial networks that traded mostly in slaves, salt, iron and copper.

Congo Free State (1877–1908)

Belgian exploration and administration took place from the 1870s until the 1920s. It was first led by Henry Morton Stanley, who undertook his explorations under the sponsorship of King Leopold II of Belgium. The eastern regions of the precolonial Congo were heavily disrupted by constant slave raiding, mainly from Arab–Swahili slave traders such as the infamous Tippu Tip, who was well known to Stanley.[35]

Leopold had designs on what was to become the Congo as a colony.[36] In a succession of negotiations, Leopold, professing humanitarian objectives in his capacity as chairman of the front organization Association Internationale Africaine, actually played one European rival against another.[citation needed]

King Leopold formally acquired rights to the Congo territory at the Conference of Berlin in 1885 and made the land his private property. He named it the Congo Free State.[36] Leopold's regime began various infrastructure projects, such as the construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), which took eight years to complete.

In the Free State, colonists coerced the local population into producing rubber, for which the spread of automobiles and development of rubber tires created a growing international market. Rubber sales made a fortune for Leopold, who built several buildings in Brussels and Ostend to honor himself and his country. To enforce the rubber quotas, the Force Publique was called in and made the practice of cutting off the limbs of the natives a matter of policy.[37]

During the period of 1885–1908, millions of Congolese died as a consequence of exploitation and disease. In some areas the population declined dramatically – it has been estimated that sleeping sickness and smallpox killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.[37]

News of the abuses began to circulate. In 1904, the British consul at Boma in the Congo, Roger Casement, was instructed by the British government to investigate. His report, called the Casement Report, confirmed the accusations of humanitarian abuses. The Belgian Parliament forced Leopold II to set up an independent commission of inquiry. Its findings confirmed Casement's report of abuses, concluding that the population of the Congo had been "reduced by half" during this period.[38] Determining precisely how many people died is impossible, as no accurate records exist.

Belgian Congo (1908–1960)

In 1908, the Belgian parliament, in spite of initial reluctance, bowed to international pressure (especially from the United Kingdom) and took over the Free State from King Leopold II.[39] On 18 October 1908, the Belgian parliament voted in favour of annexing the Congo as a Belgian colony. Executive power went to the Belgian minister of colonial affairs, assisted by a Colonial Council (Conseil Colonial) (both located in Brussels). The Belgian parliament exercised legislative authority over the Belgian Congo. In 1923 the colonial capital moved from Boma to Léopoldville, some 300 kilometres (190 mi) further upstream into the interior.[40]

The transition from the Congo Free State to the Belgian Congo was a break, but it also featured a large degree of continuity. The last governor-general of the Congo Free State, Baron Théophile Wahis, remained in office in the Belgian Congo and the majority of Leopold II's administration with him.[41] Opening up the Congo and its natural and mineral riches to the Belgian economy remained the main motive for colonial expansion – however, other priorities, such as healthcare and basic education, slowly gained in importance.

Colonial administrators ruled the territory and a dual legal system existed (a system of European courts and another one of indigenous courts, tribunaux indigènes). Indigenous courts had only limited powers and remained under the firm control of the colonial administration. The Belgian authorities permitted no political activity in the Congo whatsoever,[42] and the Force Publique put down any attempts at rebellion.

The Belgian Congo was directly involved in the two world wars. During World War I (1914–1918), an initial stand-off between the Force Publique and the German colonial army in German East Africa turned into open warfare with a joint Anglo-Belgian-Portuguese invasion of German colonial territory in 1916 and 1917 during the East African campaign. The Force Publique gained a notable victory when it marched into Tabora in September 1916 under the command of General Charles Tombeur after heavy fighting.

After 1918, Belgium was rewarded for the participation of the Force Publique in the East African campaign with a League of Nations mandate over the previously German colony of Ruanda-Urundi. During World War II, the Belgian Congo provided a crucial source of income for the Belgian government in exile in London, and the Force Publique again participated in Allied campaigns in Africa. Belgian Congolese forces under the command of Belgian officers notably fought against the Italian colonial army in Ethiopia in Asosa, Bortaï[43] and Saïo under Major-General Auguste-Eduard Gilliaert.[44]

Independence and political crisis (1960–1965)

In May 1960, a growing nationalist movement, the Mouvement National Congolais led by Patrice Lumumba, won the parliamentary elections. Lumumba became the first Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo, on 24 June 1960. The parliament elected Joseph Kasa-Vubu as president, of the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO) party. Other parties that emerged included the Parti Solidaire Africain led by Antoine Gizenga, and the Parti National du Peuple led by Albert Delvaux and Laurent Mbariko.[45]

The Belgian Congo achieved independence on 30 June 1960 under the name "République du Congo" ("Republic of Congo" or "Republic of the Congo" in English). As the neighboring French colony of Middle Congo (Moyen Congo) also chose the name "Republic of Congo" upon achieving its independence, the two countries were more commonly known as "Congo-Léopoldville" and "Congo-Brazzaville", after their capital cities.

Shortly after independence the Force Publique mutinied, and on 11 July the province of Katanga (led by Moïse Tshombe) and South Kasai engaged in secessionist struggles against the new leadership.[46][47] Most of the 100,000 Europeans who had remained behind after independence fled the country,[48] opening the way for Congolese to replace the European military and administrative elite.[49] After the United Nations rejected Lumumba's call for help to put down the secessionist movements, Lumumba asked for assistance from the Soviet Union, who accepted and sent military supplies and advisers. On 23 August, the Congolese armed forces invaded South Kasai. Lumumba was dismissed from office on 5 September 1960 by Kasa-Vubu who publicly blamed him for massacres by the armed forces in South Kasai and for involving Soviets in the country.[50] Lumumba declared Kasa-Vubu's action unconstitutional, and a crisis between the two leaders developed.[51]

On 14 September, Colonel Joseph Mobutu, with the backing of the US and Belgium, removed Lumumba from office. On 17 January 1961, Lumumba was handed over to Katangan authorities and executed by Belgian-led Katangan troops.[52] A 2001 investigation by Belgium's Parliament found Belgium "morally responsible" for the murder of Lumumba, and the country has since officially apologised for its role in his death.[53]

On 18 September 1961, in ongoing negotiations of a ceasefire, a plane crash near Ndola resulted in the death of Dag Hammarskjöld, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, along with all 15 passengers, setting off a succession crisis. Amidst widespread confusion and chaos, a temporary government was led by technicians (the Collège des commissaires généraux). Katangan secession ended in January 1963 with the assistance of UN forces. Several short-lived governments of Joseph Ileo, Cyrille Adoula, and Moise Kapenda Tshombe took over in quick succession.

Meanwhile, in the east of the country, Soviet and Cuban-backed rebels called the Simbas rose up, taking a significant amount of territory and proclaiming a communist "People's Republic of the Congo" in Stanleyville. The Simbas were pushed out of Stanleyville in November 1964 during Operation Dragon Rouge, a military operation conducted by Belgian and American forces to rescue hundreds of hostages. Congolese government forces fully defeated the Simba rebels by November 1965.[54]

Lumumba had previously appointed Mobutu chief of staff of the new Congo army, Armée Nationale Congolaise.[55] Taking advantage of the leadership crisis between Kasavubu and Tshombe, Mobutu garnered enough support within the army to launch a coup. A constitutional referendum the year before Mobutu's coup of 1965 resulted in the country's official name being changed to the "Democratic Republic of the Congo."[2] In 1971 Mobutu changed the name again, this time to "Republic of Zaire".[56][22]

Mobutu dictatorship and Zaire (1965–1997)

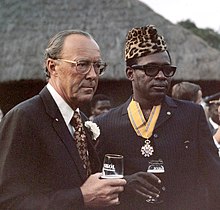

Mobutu had the staunch support of the United States because of his opposition to communism; the U.S. believed that his administration would serve as an effective counter to communist movements in Africa.[57] A single-party system was established, and Mobutu declared himself head of state. He periodically held elections in which he was the only candidate. Although relative peace and stability were achieved, Mobutu's government was guilty of severe human rights violations, political repression, a cult of personality and corruption.

By late 1967 Mobutu had successfully neutralized his political opponents and rivals, either through co-opting them into his regime, arresting them, or rendering them otherwise politically impotent.[58] Throughout the late 1960s, Mobutu continued to shuffle his governments and cycle officials in and out of the office to maintain control. Joseph Kasa-Vubu's death in April 1969 ensured that no person with First Republic credentials could challenge his rule.[59] By the early 1970s, Mobutu was attempting to assert Zaire as a leading African nation. He traveled frequently across the continent while the government became more vocal about African issues, particularly those relating to the southern region. Zaire established semi-clientelist relationships with several smaller African states, especially Burundi, Chad, and Togo.[60]

Corruption became so common the term "le mal Zairois" or "Zairian sickness",[61] meaning gross corruption, theft and mismanagement, was coined, reportedly by Mobutu.[62] International aid, most often in the form of loans, enriched Mobutu while he allowed national infrastructure such as roads to deteriorate to as little as one-quarter of what had existed in 1960. Zaire became a kleptocracy as Mobutu and his associates embezzled government funds.

In a campaign to identify himself with African nationalism, starting on 1 June 1966, Mobutu renamed the nation's cities: Léopoldville became Kinshasa (the country was known as Congo-Kinshasa), Stanleyville became Kisangani, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Coquilhatville became Mbandaka. In 1971, Mobutu renamed the country the Republic of Zaire,[22] its fourth name change in eleven years and its sixth overall. The Congo River was renamed the Zaire River.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Mobutu was invited to visit the United States on several occasions, meeting with U.S. Presidents Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.[63] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union U.S. relations with Mobutu cooled, as he was no longer deemed necessary as a Cold War ally. Opponents within Zaire stepped up demands for reform. This atmosphere contributed to Mobutu's declaring the Third Republic in 1990, whose constitution was supposed to pave the way for democratic reform. The reforms turned out to be largely cosmetic. Mobutu continued in power until armed forces forced him to flee in 1997. "From 1990 to 1993, the United States facilitated Mobutu's attempts to hijack political change", one academic wrote, and "also assisted the rebellion of Laurent-Desire Kabila that overthrew the Mobutu regime."[64]

In September 1997, Mobutu died in exile in Morocco.[65]

Continental and civil wars (1996–2007)

By 1996, following the Rwandan Civil War and genocide and the ascension of a Tutsi-led government in Rwanda, Rwandan Hutu militia forces (Interahamwe) fled to eastern Zaire and used refugee camps as bases for incursions against Rwanda. They allied with the Zairian Armed Forces to launch a campaign against Congolese ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire.[66]

A coalition of Rwandan and Ugandan armies invaded Zaire to overthrow the government of Mobutu, launching the First Congo War. The coalition allied with some opposition figures, led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, becoming the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo. In 1997 Mobutu fled and Kabila marched into Kinshasa, naming himself as president and reverting the name of the country to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[67][68]

Kabila later requested that foreign military forces return to their own countries. Rwandan troops retreated to Goma and launched a new Tutsi-led rebel military movement called the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Democratie to fight Kabila, while Uganda instigated the creation of a rebel movement called the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, led by Congolese warlord Jean-Pierre Bemba.[citation needed] The two rebel movements, along with Rwandan and Ugandan troops, started the Second Congo War by attacking the DRC army in 1998. Angolan, Zimbabwean, and Namibian militaries entered the hostilities on the side of the government.

Kabila was assassinated in 2001.[69] His son Joseph Kabila succeeded him [70] and called for multilateral peace talks. UN peacekeepers, MONUC, now known as MONUSCO, arrived in April 2001. In 2002–03 Bemba intervened in the Central African Republic on behalf of its former president, Ange-Félix Patassé.[71] Talks led to a peace accord under which Kabila would share power with former rebels. By June 2003 all foreign armies except those of Rwanda had pulled out of Congo. A transitional government was set up until after the election. A constitution was approved by voters, and on 30 July 2006 DRC held its first multi-party elections. These were the first free national elections since 1960, which many believed would mark the end to violence in the region.[72] However, an election-result dispute between Kabila and Bemba turned into a skirmish between their supporters in Kinshasa. MONUC took control of the city. A new election took place in October 2006, which Kabila won, and in December 2006 he was sworn in as president.

Continued conflicts (2008–2018)

Kivu conflict

Laurent Nkunda, a member of Rally for Congolese Democracy–Goma, a Rally for Congolese Democracy branch integrated to the army, defected along with troops loyal to him and formed the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), which began an armed rebellion against the government. They were believed[by whom?] to be again backed by Rwanda as a way to tackle the Hutu group, Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). In March 2009, after a deal between the DRC and Rwanda, Rwandan troops entered the DRC and arrested Nkunda and were allowed to pursue FDLR militants. The CNDP signed a peace treaty with the government in which it agreed to become a political party and to have its soldiers integrated into the national army in exchange for the release of its imprisoned members.[73] In 2012 Bosco Ntaganda, the leader of the CNDP, and troops loyal to him, mutinied and formed the rebel military March 23 Movement (M23), claiming the government had violated the treaty.[74]

In the resulting M23 rebellion, M23 briefly captured the provincial capital of Goma in November 2012.[75][76] Neighboring countries, particularly Rwanda, have been accused of arming rebels groups and using them as proxies to gain control of the resource-rich country, an accusation they deny.[77][78] In March 2013, the United Nations Security Council authorized the United Nations Force Intervention Brigade to neutralize armed groups.[79] On 5 November 2013, M23 declared an end to its insurgency.[80]

Additionally, in northern Katanga, the Mai-Mai created by Laurent Kabila slipped out of the control of Kinshasa with Gédéon Kyungu Mutanga's Mai Mai Kata Katanga briefly invading the provincial capital of Lubumbashi in 2013 and 400,000 persons displaced in the province as of 2013[update].[81] On and off fighting in the Ituri conflict occurred between the Nationalist and Integrationist Front and the Union of Congolese Patriots who claimed to represent the Lendu and Hema ethnic groups, respectively. In the northeast, Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army moved from their original bases in Uganda and South Sudan to DR Congo in 2005 and set up camps in the Garamba National Park.[82][83]

The war in the Congo has been described as the bloodiest war since World War II.[14] On 8 December 2017, fourteen UN soldiers and five Congolese regular soldiers were killed in a rebel attack at Semuliki in Beni territory. The rebels were thought to be Allied Democratic Forces.[84] UN investigations confirmed that aggressor in the December attack.[85]

In 2009, The New York Times reported that people in the Congo continued to die at a rate of an estimated 45,000 per month[86] – estimates of the number who have died from the long conflict range from 900,000 to 5,400,000.[87] The death toll is caused by widespread disease and famine; reports indicate that almost half of the individuals who have died are children under five years of age.[88] There have been frequent reports of weapon bearers killing civilians, of the destruction of property, of widespread sexual violence,[89] causing hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes, and of other breaches of humanitarian and human rights law. One study found that more than 400,000 women are raped in the Democratic Republic of Congo every year.[90] In 2018 and 2019, Congo reported the highest levels of sexual violence in the world.[72] According to the Human Rights Watch and the New York University-based Congo Research Group, armed troops in DRC's eastern Kivu region have killed over 1,900 civilians and kidnapped at least 3,300 people since June 2017 to June 2019.[91]

Kabila's term in office and multiple anti-government protests

In 2015, major protests broke out across the country and protesters demanded that Kabila step down as president. The protests began after the passage of a law by the Congolese lower house that, if also passed by the Congolese upper house, would keep Kabila in power at least until a national census was conducted (a process which would likely take several years and therefore keep him in power past the planned 2016 elections, which he is constitutionally barred from participating in). This bill passed; however, it was gutted of the provision that would keep Kabila in power until a census took place. A census is supposed to take place, but it is no longer tied to when the elections take place. In 2015, elections were scheduled for late 2016 and a tenuous peace held in the Congo.[92]

On 27 November 2016 Congolese foreign minister Raymond Tshibanda told the press no elections would be held in 2016, after 20 December, the end of president Kabila's term. In a conference in Madagascar, Tshibanda said that Kabila's government had "consulted election experts" from Congo, the United Nations and elsewhere, and that "it has been decided that the voter registration operation will end on July 31, 2017, and that election will take place in April 2018."[93] Protests broke out in the country on 20 December when Kabila's term in office ended. Across the country, dozens of protesters were killed and hundreds were arrested.

Renewed regional violence

According to Jan Egeland, presently Secretary-General of the Norwegian Refugee Council, the situation in the DRC became much worse in 2016 and 2017 and is a major moral and humanitarian challenge comparable to the wars in Syria and Yemen, which receive much more attention. Women and children are abused sexually and "abused in all possible manners". Besides the conflict in North Kivu, violence increased in the Kasai region. The armed groups were after gold, diamonds, oil, and cobalt to line the pockets of rich men both in the region and internationally. There were also ethnic and cultural rivalries at play, as well as religious motives and the political crisis with postponed elections. Egeland says people believe the situation in the DRC is "stably bad" but in fact, it has become much, much worse. "The big wars of the Congo that were really on top of the agenda 15 years ago are back and worsening".[94] Disruption in planting and harvesting caused by the conflict was estimated to escalate starvation in about two million children.[95]

Human Rights Watch said in 2017 that Kabila recruited former March 23 Movement fighters to put down country-wide protests over his refusal to step down from office at the end of his term. "M23 fighters patrolled the streets of Congo's main cities, firing on or arresting protesters or anyone else deemed to be a threat to the president," they said.[96]

Fierce fighting has erupted in Masisi between government forces and a powerful local warlord, General Delta. The United Nations mission in the DRC is its largest and most expensive peacekeeping effort, but it shut down five UN bases near Masisi in 2017, after the U.S. led a push to cut costs.[97]

On 10 May 2018, Congolese gynecologist Denis Mukwege was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his effort to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict.[98]

2018 ethnic conflict

A tribal conflict erupted on 16–17 December 2018 at Yumbi in Mai-Ndombe Province. Nearly 900 Banunu people from four villages were slaughtered by members of the Batende community in a deep-rooted rivalry over monthly tribal duties, land, fields and water resources. Some 100 Banunus fled to Moniende island in the Congo River, and another 16,000 to Makotimpoko District in Republic of Congo. Military-style tactics were employed in the bloodbath, and some assailants were clothed in army uniforms. Local authorities and elements within the security forces were suspected of lending them support.[99]

2018 election and new president (2018–present)

On 30 December 2018 a general election was held. On 10 January 2019, the electoral commission announced opposition candidate Félix Tshisekedi as the winner of the presidential vote,[100] and he was officially sworn in as president on 24 January.[101] However, there were widespread suspicions that the results were rigged and that a deal had been made between Tshisekedi and Kabila. The Catholic Church said that the official results did not correspond to the information its election monitors had collected.[102] The government had also "delayed" the vote until March in some areas, citing the Ebola outbreak in Kivu as well as the ongoing military conflict. This was criticized as these regions are known as opposition strongholds.[103][104][105] In August 2019, six months after the inauguration of Félix Tshisekedi, a coalition government was announced.[106]

The political allies of Kabila maintained control of key ministries, the legislature, judiciary and security services. However, Tshisekedi succeeded in strengthening his hold on power. In a series of moves, he won over more legislators, gaining the support of almost 400 out of 500 members of the National Assembly. The pro-Kabila speakers of both houses of parliament were forced out. In April 2021, the new government was formed without the supporters of Kabila.[107]

A major measles outbreak in the country left nearly 5,000 dead in 2019.[108] The Ebola outbreak ended in June 2020, which had caused 2,280 deaths over 2 years.[109] Another, smaller Ebola outbreak in the Équateur Province began in June 2020, ultimately causing 55 deaths.[110][111] The global COVID-19 pandemic also reached the DRC in March 2020, with a vaccination campaign beginning on 19 April 2021.[112][113]

The Italian ambassador to the DRC, Luca Attanasio, and his bodyguard were killed in North Kivu on 22 February 2021.[114] On 22 April 2021, meetings between Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and Tshisekedi resulted in new agreements increasing international trade and security (counterterrorism, immigration, cyber security, and customs) between the two countries.[115] In February 2022, allegations of a coup d'état in the country led to uncertainty,[116] but the coup attempt failed.[117]

Geography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

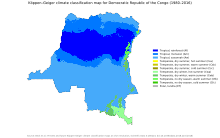

The DRC is located in central sub-Saharan Africa, bordered to the northwest by the Republic of the Congo, to the north by the Central African Republic, to the northeast by South Sudan, to the east by Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi, and by Tanzania (across Lake Tanganyika), to the south and southeast by Zambia, to the southwest by Angola, and to the west by the South Atlantic Ocean and the Cabinda Province exclave of Angola. The country lies between latitudes 6°N and 14°S, and longitudes 12°E and 32°E. It straddles the Equator, with one-third to the north and two-thirds to the south. With an area of 2,345,408 square kilometres (905,567 sq mi), it is the second-largest country in Africa by area, after Algeria.

As a result of its equatorial location, the DRC experiences high precipitation and has the highest frequency of thunderstorms in the world. The annual rainfall can total upwards of 2,000 millimetres (80 in) in some places, and the area sustains the Congo rainforest, the second-largest rain forest in the world after the Amazon rainforest. This massive expanse of lush jungle covers most of the vast, low-lying central basin of the river, which slopes toward the Atlantic Ocean in the west. This area is surrounded by plateaus merging into savannas in the south and southwest, by mountainous terraces in the west, and dense grasslands extending beyond the Congo River in the north. The glaciated Rwenzori Mountains are found in the extreme eastern region.

The tropical climate produced the Congo River system which dominates the region topographically along with the rainforest it flows through. The Congo Basin occupies nearly the entire country and an area of nearly 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi). The river and its tributaries form the backbone of Congolese economics and transportation. Major tributaries include the Kasai, Sangha, Ubangi, Ruzizi, Aruwimi, and Lulonga.

The Congo River has the second-largest flow and the second-largest watershed of any river in the world (trailing the Amazon in both respects). The sources of the Congo River are in the Albertine Rift Mountains that flank the western branch of the East African Rift, as well as Lake Tanganyika and Lake Mweru. The river flows generally west from Kisangani just below Boyoma Falls, then gradually bends southwest, passing by Mbandaka, joining with the Ubangi River, and running into the Pool Malebo (Stanley Pool). Kinshasa and Brazzaville are on opposite sides of the river at the Pool. Then the river narrows and falls through a number of cataracts in deep canyons, collectively known as the Livingstone Falls, and runs past Boma into the Atlantic Ocean. The river and a 37-kilometre-wide (23 mi) strip of coastline on its north bank provide the country's only outlet to the Atlantic.

The Albertine Rift plays a key role in shaping the Congo's geography. Not only is the northeastern section of the country much more mountainous, but tectonic movement results in volcanic activity, occasionally with loss of life. The geologic activity in this area also created the African Great Lakes, four of which lie on the Congo's eastern frontier: Lake Albert, Lake Kivu, Lake Edward, and Lake Tanganyika.

The rift valley has exposed an enormous amount of mineral wealth throughout the south and east of the Congo, making it accessible to mining. Cobalt, copper, cadmium, industrial and gem-quality diamonds, gold, silver, zinc, manganese, tin, germanium, uranium, radium, bauxite, iron ore, and coal are all found in plentiful supply, especially in the Congo's southeastern Katanga region.[118]

On 17 January 2002, Mount Nyiragongo erupted, with three streams of extremely fluid lava running out at 64 km/h (40 mph) and 46 m (50 yd) wide. One of the three streams flowed directly through Goma, killing 45 people and leaving 120,000 homeless. Over 400,000 people were evacuated from the city during the eruption. The lava flowed into and poisoned the water of Lake Kivu killing its plants, animals and fish. Only two planes left the local airport because of the possibility of the explosion of stored petrol. The lava flowed through and past the airport, destroying a runway and trapping several parked airplanes. Six months after the event, nearby Mount Nyamuragira also erupted. The mountain subsequently erupted again in 2006, and once again in January 2010.[119]

Biodiversity and conservation

The rainforests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo contain great biodiversity, including many rare and endemic species, such as the common chimpanzee and the bonobo (or pygmy chimpanzee), the African forest elephant, mountain gorilla, okapi, forest buffalo, leopard and, further south in the country, the southern white rhinoceros. Five of the country's national parks are listed as World Heritage Sites: the Garumba, Kahuzi-Biega, Salonga and Virunga National Parks, and the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of 17 Megadiverse countries and is the most biodiverse African country.[120]

Conservationists have particularly worried about primates. The Congo is inhabited by several great ape species: the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), the bonobo (Pan paniscus), the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei), and possibly a population of the western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla).[121] It is the only country in the world in which bonobos are found in the wild. Much concern has been raised about great ape extinction. Because of hunting and habitat destruction, the numbers of chimpanzee, bonobo and gorilla (each of whose populations once numbered in the millions) have now dwindled down to only about 200,000 gorillas, 100,000 chimpanzees and possibly only about 10,000 bonobos.[122][123] The gorillas, chimpanzee, bonobo, and okapi are all classified as endangered by the World Conservation Union.

Major environmental issues in DRC include deforestation, poaching, which threatens wildlife populations, water pollution and mining. From 2015 to 2019, the rate of deforestation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo doubled.[124] In 2021, deforestation of the Congolian rainforests increased by 5%.[125]

Administrative divisions

The country is currently divided into the city-province of Kinshasa and 25 other provinces.[2] The provinces are subdivided into 145 territories and 32 cities. Before 2015, the country had 11 provinces.[126]

|

1. Kinshasa | 14. Ituri Province |

| 2. Kongo Central | 15. Haut-Uele | |

| 3. Kwango | 16. Tshopo | |

| 4. Kwilu Province | 17. Bas-Uele | |

| 5. Mai-Ndombe Province | 18. Nord-Ubangi | |

| 6. Kasaï Province | 19. Mongala | |

| 7. Kasaï-Central | 20. Sud-Ubangi | |

| 8. Kasaï-Oriental | 21. Équateur | |

| 9. Lomami Province | 22. Tshuapa | |

| 10. Sankuru | 23. Tanganyika Province | |

| 11. Maniema | 24. Haut-Lomami | |

| 12. South Kivu | 25. Lualaba Province | |

| 13. North Kivu | 26. Haut-Katanga Province |

Government and politics

After a four-year interlude between two constitutions, with new political institutions established at the various levels of government, as well as new administrative divisions for the provinces throughout the country, a new constitution came into effect in 2006 and politics in the Democratic Republic of the Congo finally settled into a stable presidential democratic republic. The 2003 transitional constitution[127] had established a parliament with a bicameral legislature, consisting of a Senate and a National Assembly.

The Senate had, among other things, the charge of drafting the new constitution of the country. The executive branch was vested in a 60-member cabinet, headed by a President and four vice presidents. The President was also the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The transitional constitution also established a relatively independent judiciary, headed by a Supreme Court with constitutional interpretation powers.[128]

The 2006 constitution, also known as the Constitution of the Third Republic, came into effect in February 2006. It had concurrent authority, however, with the transitional constitution until the inauguration of the elected officials who emerged from the July 2006 elections. Under the new constitution, the legislature remained bicameral; the executive was concomitantly undertaken by a President and the government, led by a Prime Minister, appointed from the party able to secure a majority in the National Assembly.

The government – not the President – is responsible to the Parliament. The new constitution also granted new powers to the provincial governments, creating provincial parliaments which have oversight of the Governor and the head of the provincial government, whom they elect. The new constitution also saw the disappearance of the Supreme Court, which was divided into three new institutions. The constitutional interpretation prerogative of the Supreme Court is now held by the Constitutional Court.[129]

Although located in the Central African UN subregion, the nation is also economically and regionally affiliated with Southern Africa as a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).[130]

Foreign relations

The global growth in demand for scarce raw materials and the industrial surges in China, India, Russia, Brazil and other developing countries require that developed countries employ new, integrated and responsive strategies for identifying and ensuring, on a continual basis, an adequate supply of strategic and critical materials required for their security needs.[131] Highlighting the DR Congo's importance to United States national security, the effort to establish an elite Congolese unit is the latest push by the U.S. to professionalize armed forces in this strategically important region.[132]

There are economic and strategic incentives to bring more security to the Congo, which is rich in natural resources such as cobalt, a strategic and critical metal used in many industrial and military applications.[131] The largest use of cobalt is in superalloys, used to make jet engine parts. Cobalt is also used in magnetic alloys and in cutting and wear-resistant materials such as cemented carbides. The chemical industry consumes significant quantities of cobalt in a variety of applications including catalysts for petroleum and chemical processing; drying agents for paints and inks; ground coats for porcelain enamels; decolorant for ceramics and glass; and pigments for ceramics, paints, and plastics. The country possesses 80% of the world's cobalt reserves.[133]

It is thought that due to the importance of cobalt for batteries for electric vehicles and stabilization of electric grids with large proportions of intermittent renewables in the electricity mix, the DRC could become an object of increased geopolitical competition.[131]

In the 21st century, Chinese investment in the DRC and Congolese exports to China have grown rapidly. In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including DRC, have signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic minorities.[134] In 2021, President Félix Tshisekedi called for a review of mining contracts signed with China by his predecessor Joseph Kabila,[135] in particular the Sicomines multibillion 'minerals-for-infrastructure' deal.[136][137]

Military

The Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) consist of about 144,000 personnel, the majority of whom are part of the land forces, also with a small air force and an even smaller navy. The FARDC was established in 2003 after the end of the Second Congo War and integrated many former rebel groups into its ranks. Due to the presence of undisciplined and poorly trained ex-rebels, as well as a lack of funding and having spent years fighting against different militias, the FARDC suffers from rampant corruption and inefficiency. The agreements signed at the end of the Second Congo War called for a new "national, restructured and integrated" army that would be made up of Kabila's government forces (the FAC), the RCD, and the MLC. Also stipulated was that rebels like the RCD-N, RCD-ML, and the Mai-Mai would become part of the new armed forces. It also provided for the creation of a Conseil Supérieur de la Défense (Superior Defence Council) which would declare states of siege or war and give advice on security sector reform, disarmament/demobilisation, and national defence policy. The FARDC is organised on the basis of brigades, which are dispersed throughout the provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Congolese troops have been fighting the Kivu conflict in the eastern North Kivu region, the Ituri conflict in the Ituri region, and other rebellions since the Second Congo War. Besides the FARDC, the largest peacekeeping mission of the United Nations, known as MONUSCO, is also present in the country with about 18,000 peacekeepers.

The Democratic Republic of Congo signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[138]

Corruption

A relative of Mobutu explained how the government illicitly collected revenue during his rule: "Mobutu would ask one of us to go to the bank and take out a million. We'd go to an intermediary and tell him to get five million. He would go to the bank with Mobutu's authority and take out ten. Mobutu got one, and we took the other nine."[139] Mobutu institutionalized corruption to prevent political rivals from challenging his control, leading to an economic collapse in 1996.[140]

Mobutu allegedly stole as much as US$4–5 billion while in office.[141] He was not the first corrupt Congolese leader by any means: "Government as a system of organized theft goes back to King Leopold II," noted Adam Hochschild in 2009.[142] In July 2009, a Swiss court determined that the statute of limitations had run out on an international asset recovery case of about $6.7 million of deposits of Mobutu's in a Swiss bank, and therefore the assets should be returned to Mobutu's family.[143]

President Kabila established the Commission of Repression of Economic Crimes upon his ascension to power in 2001.[144] However, in 2016 the Enough Project issued a report claiming that the Congo is run as a violent kleptocracy.[145]

In June 2020, a court in the Democratic Republic of Congo found President Tshisekedi's chief of staff Vital Kamerhe guilty of corruption. He was sentenced to 20 years' hard labour, after facing charges of embezzling almost $50m (£39m) of public funds. He was the most high-profile figure to be convicted of corruption in the DRC.[146] However, Kamerhe was released already in December 2021.[147]

In November 2021, a judicial investigation targeting Kabila and his associates was opened in Kinshasa after revelations of alleged embezzlement of $138 million.[148]

Human rights

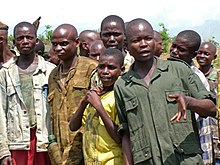

The International Criminal Court investigation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was initiated by Kabila in April 2004. The International Criminal Court prosecutor opened the case in June 2004. Child soldiers have been used on a large scale in DRC, and in 2011 it was estimated that 30,000 children were still operating with armed groups.[149] Instances of child labor and forced labor have been observed and reported in the U.S. Department of Labor's Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor in the DRC in 2013[150] and six goods produced by the country's mining industry appear on the department's December 2014 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has prohibited same-sex marriage since 2006,[151] and attitudes towards the LGBT community are generally negative throughout the nation.[152]

Crime and law enforcement

The Congolese National Police are the primary police force in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[153]

Violence against womenedit

Violence against women seems to be perceived by large sectors of society to be normal.[154] The 2013–2014 DHS survey (pp. 299) found that 74.8% of women agreed that a husband is justified in beating his wife in certain circumstances.[155]

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women in 2006 expressed concern that in the post-war transition period, the promotion of women's human rights and gender equality is not seen as a priority.[156][157] Mass rapes, sexual violence and sexual slavery are used as a weapon of war by the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and armed groups in the eastern part of the country.[158] The eastern part of the country in particular has been described as the "rape capital of the world" and the prevalence of sexual violence there described as the worst in the world.[159][160]

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is also practiced in DRC, although not on a large scale. The prevalence of FGM is estimated at 5% of women.[161][162] FGM is illegal: the law imposes a penalty of two to five years of prison and a fine of 200,000 Congolese francs on any person who violates the "physical or functional integrity" of the genital organs.[163][164]

In July 2007, the International Committee of the Red Cross expressed concern about the situation in eastern DRC.[165] A phenomenon of "pendulum displacement" has developed, where people hasten at night to safety. According to Yakin Ertürk, the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women who toured eastern Congo in July 2007, violence against women in North and South Kivu included "unimaginable brutality". Ertürk added that "Armed groups attack local communities, loot, rape, kidnap women and children, and make them work as sexual slaves".[166] In December 2008, GuardianFilms of The Guardian released a film documenting the testimony of over 400 women and girls who had been abused by marauding militia.[167]

In June 2010, Oxfam reported a dramatic increase in the number of rapes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and researchers from Harvard discovered that rapes committed by civilians had increased seventeenfold.[168] In June 2014, Freedom from Torture published reported rape and sexual violence being used routinely by state officials in Congolese prisons as punishment for politically active women.[169] The women included in the report were abused in several locations across the country including the capital Kinshasa and other areas away from the conflict zones.[169]

In 2015, figures both inside and outside of the country, such as Filimbi and Emmanuel Weyi, spoke out about the need to curb violence and instability as the 2016 elections approached.[170][171]

Economyedit

The Central Bank of the Congo is responsible for developing and maintaining the Congolese franc, which serves as the primary form of currency in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 2007, The World Bank decided to grant the Democratic Republic of Congo up to $1.3 billion in assistance funds over the following three years.[172] The Congolese government started negotiating membership in the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA), in 2009.[173]

The DRC is widely considered one of the world's richest countries in natural resources; its untapped deposits of raw minerals are estimated to be worth in excess of US$24 trillion.[174][175][176] The DRC has 70% of the world's coltan, a third of its cobalt, more than 30% of its diamond reserves, and a tenth of its copper.[177][178]

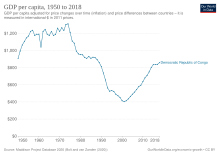

Despite such vast mineral wealth, the economy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo has declined drastically since the mid-1980s. The DRC generated up to 70% of its export revenue from minerals in the 1970s and 1980s and was particularly hit when resource prices deteriorated at that time. By 2005, 90% of the DRC's revenues derived from its minerals.[179] Congolese citizens are among the poorest people on Earth. DR Congo consistently has the lowest, or nearly the lowest, nominal GDP per capita in the world. The DRC is also one of the twenty lowest-ranked countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index.

Miningedit

The DRC is the world's largest producer of cobalt ore, and a major producer of copper and diamonds.[180] The latter come from Kasaï Province in the west. By far the largest mines in the DRC are located in southern Katanga Province and are highly mechanized, with a capacity of several million tons per year of copper and cobalt ore, and refining capability for metal ore. The DRC is the second-largest diamond-producing nation in the world,[b] and artisanal and small-scale miners account for most of its production.

At independence in 1960, DRC was the second-most-industrialized country in Africa after South Africa; it boasted a thriving mining sector and a relatively productive agriculture sector.[181] Foreign businesses have curtailed operations because of uncertainty about the outcome of long-term conflicts, lack of infrastructure, and the difficult operating environment. The wars intensified the impact of such basic problems as an uncertain legal framework, corruption, inflation, and lack of openness in government economic policy and financial operations.

Conditions improved in late 2002, when a large portion of the invading foreign troops withdrew. A number of International Monetary Fund and World Bank missions met with the government to help it develop a coherent economic plan, and President Kabila began implementing reforms. Much economic activity still lies outside the GDP data. Through 2011 the DRC had the lowest Human Development Index of the 187 ranked countries.[182]

The economy of DRC relies heavily on mining. However, the smaller-scale economic activity from artisanal mining occurs in the informal sector and is not reflected in GDP data.[183] A third of the DRC's diamonds are believed to be smuggled out of the country, making it difficult to quantify diamond production levels.[184] In 2002, tin was discovered in the east of the country but to date has only been mined on a small scale.[185] Smuggling of conflict minerals such as coltan and cassiterite, ores of tantalum and tin, respectively, helped to fuel the war in the eastern Congo.[186]

Katanga Mining Limited, a Swiss-owned company, owns the Luilu Metallurgical Plant, which has a capacity of 175,000 tonnes of copper and 8,000 tonnes of cobalt per year, making it the largest cobalt refinery in the world. After a major rehabilitation program, the company resumed copper production operations in December 2007 and cobalt production in May 2008.[187]

In April 2013, anti-corruption NGOs revealed that Congolese tax authorities had failed to account for $88 million from the mining sector, despite booming production and positive industrial performance. The missing funds date from 2010 and tax bodies should have paid them into the central bank.[188] Later in 2013, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative suspended the country's candidacy for membership due to insufficient reporting, monitoring and independent audits, but in July 2013 the country improved its accounting and transparency practices to the point where the EITI gave the country full membership.

In February 2018, global asset management firm AllianceBernstein[189] defined the DRC as economically "the Saudi Arabia of the electric vehicle age," because of its cobalt resources, as essential to the lithium-ion batteries that drive electric vehicles.[190]

Transportationedit

Ground transport in the Democratic Republic of Congo has always been difficult. The terrain and climate of the Congo Basin present serious barriers to road and rail construction, and the distances are enormous across this vast country. The DRC has more navigable rivers and moves more passengers and goods by boat and ferry than any other country in Africa, but air transport remains the only effective means of moving goods and people between many places within the country, especially in rural areas. Chronic economic mismanagement, political corruption and internal conflicts have led to long-term under-investment of infrastructure.

Railedit

Rail transportation is provided by the Congo Railroad Company (Société nationale des chemins de fer du Congo), the Office National des Transports Congo and the Office of the Uele Railways (Office des Chemins de fer des Ueles, CFU).

Roadedit

The DRC has fewer all-weather paved highways than any country of its population and size in Africa — a total of 2,250 km (1,400 mi), of which only 1,226 km (762 mi) is in good condition. To put this in perspective, the road distance across the country in any direction is more than 2,500 km (1,600 mi) (e.g. Matadi to Lubumbashi, 2,700 km (1,700 mi) by road). The figure of 2,250 km (1,400 mi) converts to 35 km (22 mi) of paved road per 1 million of population. Comparative figures for Zambia and Botswana are 721 km (448 mi) and 3,427 km (2,129 mi), respectively.[c]

Three routes in the Trans-African Highway network pass through DR Congo:

- Tripoli–Cape Town Highway: this route crosses the western extremity of the country on National Road No. 1 between Kinshasa and Matadi, a distance of 285 km (177 mi) on one of the only paved sections in fair condition.

- Lagos–Mombasa Highway: the DR Congo is the main missing link in this east–west highway and requires a new road to be constructed before it can function.

- Beira–Lobito Highway: this east–west highway crosses Katanga and requires re-construction over most of its length, being an earth track between the Angolan border and Kolwezi, a paved road in very poor condition between Kolwezi and Lubumbashi, and a paved road in fair condition over the short distance to the Zambian border.

Wateredit

The DRC has thousands of kilometres of navigable waterways. Traditionally water transport has been the dominant means of moving around in approximately two-thirds of the country.

Airedit

As of June 2016[update], DR Congo had one major national airline (Congo Airways) that offered flights inside DR Congo. Congo Airways was based at Kinshasa's international airport. All air carriers certified by the DRC have been banned from European Union airports by the European Commission, because of inadequate safety standards.[191]

Several international airlines service Kinshasa's international airport and a few also offer international flights to Lubumbashi International Airport.

Energyedit

Both coal and crude oil resources were mainly used domestically up to 2008. The DRC has the infrastructure for hydro-electricity from the Congo River at the Inga dams.[192] The country also possesses 50% of Africa's forests and a river system that could provide hydro-electric power to the entire continent, according to a UN report on the country's strategic significance and its potential role as an economic power in central Africa.[193]

The generation and distribution of electricity are controlled by Société nationale d'électricité, but only 15% of the country has access to electricity.[194] The DRC is a member of three electrical power pools. These are Southern African Power Pool, East African Power Pool, and Central African Power Pool.

Renewable energyedit

Because of abundant sunlight, the potential for solar development is very high in the DRC. There are already about 836 solar power systems in the DRC, with a total power of 83 MW, located in Équateur (167), Katanga (159), Nord-Kivu (170), the two Kasaï provinces (170), and Bas-Congo (170). Also, the 148 Caritas network system has a total power of 6.31 MW.[195]

Demographicsedit

Populationedit

The CIA World Factbook estimated the population to be over 111 million as of 2023.[196] Between 1950 and 2000, the country's population nearly quadrupled from 12.2 million to 46.9 million.[197]

Languagesedit

French is the official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is culturally accepted as the lingua franca, facilitating communication among the many different ethnic groups of the Congo. According to a 2018 OIF report, 49 million Congolese people (51% of the population) could read and write in French.[198] A 2021 survey found that 74% of the population could speak French, making it the most widely spoken language in the country.[199]

In Kinshasa, 67% of the population in 2014 could read and write French, and 68.5% could speak and understand it.[200]

Approximately 242 languages are spoken in the country, of which four have the status of national languages: Kituba (Kikongo), Lingala, Tshiluba, and Swahili. Although some limited number of people speak these as first languages, most of the population speak them as a second language, after the native language of their own ethnic group. Lingala was the official language of the Force Publique under Belgian colonial rule and remains to this day the predominant language of the armed forces. Since the recent rebellions, a good part of the army in the east also uses Swahili, where it competes to be the regional lingua franca.

Under Belgian rule, the Belgians instituted teaching and use of the four national languages in primary schools, making it one of the few African nations to have had literacy in local languages during the European colonial period. This trend was reversed after independence, when French became the sole language of education at all levels.[201] Since 1975, the four national languages have been reintroduced in the first two years of primary education, with French becoming the sole language of education from the third year onward, but in practice many primary schools in urban areas solely use French from the first year of school onward.[201]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Democratic_Republic_of_Congo

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.