A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article needs to be updated. (November 2020) |

Ukraine was in 96th place[1] out of 180 countries listed in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index, having returned to top 100 of this list for the first time since 2009, but dropped down one spot to 97th place in 2021, being characterized as being in a "difficult situation".

Press freedom scores had significantly improved since the Orange Revolution of 2004.[2][3][4] However, in 2010 and again in 2011 Freedom House perceived "negative trends in Ukraine" with government-critical opposition media outlets being closed.[5]

According to the Freedom House, The Ukrainian legal framework on media freedom used to be "among the most progressive in eastern Europe", although implementation has been uneven.[6] The Constitution of Ukraine and a 1991 law provide for freedom of speech.[7]

Many Ukrainian journalists found themselves internally displaced due to the Russian annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, including Donetsk-based investigative journalist Oleksiy Matsuka, Luhansk blogger Serhiy Ivanov and Donetsk Ostrov independent website editor Serhiy Harmash. The entire staff of Ostrov left the occupied Donbas areas and relocated to Kyiv.[6]

History

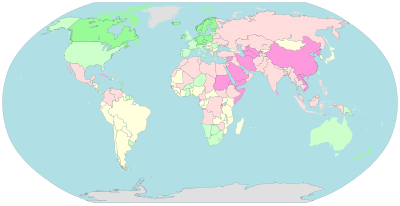

- Very serious situation

- Difficult situation

- Noticeable problems

- Satisfactory situation

- Good situation

- Not classified / No data

The Freedom in the World report by Freedom House rated Ukraine "partly free" from 1992[9] until 2003, when it was rated "not free".[10] After 2005, it was rated "partly free" again.[11][12] According to Freedom House internet in Ukraine is "Free" and the press is "Partly Free".[13][clarification needed]

Ukraine's ranking in Reporters Without Borderss' Press Freedom Index has long been around the 90th spot (89 in 2009,[14] 87 in 2008[15]), while it occupied the 112th spot in 2002[16] and even the 132nd spot in 2004.[17] In 2010 it fell to the 131st place; according to Reporters Without Borders this was the result of "the slow and steady deterioration in press freedom since Viktor Yanukovych's election as president in February".[18] In 2013 Ukraine occupied the 126th spot (dropping 10 places compared with 2012); (according to Reporters Without Borders) "the worst record for the media since the Orange Revolution in 2004".[19] In the 2017 World Press Freedom Index Ukraine was placed 102nd.[20]

During an opinion poll by Research & Branding Group in October 2009 49.2% of the respondents stated that Ukraine's level of freedom of speech was sufficient, and 19.6% said the opposite. Another 24.2% said that there was too much of freedom of speech in Ukraine. According to the data, 62% of respondents in western Ukraine considered the level of freedom of speech sufficient, and in the central and southeastern regions the figures were 44% and 47%, respectively.[21]

In a late 2010 poll also conducted by the Research & Branding Group 56% of all Ukrainians trusted the media and 38.5% didn't.[22]

Kuchma presidencies (1994–2004)

After the (only) term of office of the first Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk ended in 1994, the freedom of the press worsened.[23] During the presidency of Leonid Kuchma (1994–2004) several news-outlets critical to him were forcefully closed.[9] In 1999 the Committee to Protect Journalists placed Kuchma on the list of worst enemies of the press.[9] In that year the Ukrainian Government partially limited freedom of the press through tax inspections (Mykola Azarov, who later became Prime Minister of Ukraine, headed the tax authority during Kuchma's presidency[24][25]), libel cases, subsidization, and intimidation of journalists; this caused many journalists to practice self-censorship.[7] In 2003 and 2004 authorities interfered with the media by issuing written and oral instructions about what events to cover.[26][27] Toward the very end of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election campaign in November 2004, many media outlets began to ignore government direction and covered events in a more objective, professional manner.[27]

Orange revolution and Yushchenko presidency (2004–2010)

Since the Orange Revolution (of 2004) Ukrainian media have become more pluralistic and independent.[2][3][4] For instance, attempts by authorities to limit freedom of the press through tax inspections have ceased.[26][27][28][29][30][31] Since then the Ukrainian press is considered to be among the freest of all post-Soviet states (only the Baltic states are considered "free").[12][32][2]

After the 2005 Orange Revolution, Ukrainian television became more free.[33] In February 2009 the National Council for Television and Radio Broadcasting claimed that "political pressure on mass media increased in recent times through amending laws and other normative acts to strengthen influence on mass media and regulatory bodies in this sphere".[34]

In 2007, in Ukraine's provinces numerous, anonymous attacks[35] and threats persisted against journalists, who investigated or exposed corruption or other government misdeeds.[36][37] The US-based Committee to Protect Journalists concluded in 2007 that these attacks, and police reluctance in some cases to pursue the perpetrators, were "helping to foster an atmosphere of impunity against independent journalists."[38][39]

In Ukraine's provinces numerous, anonymous attacks[4][40][41][42] and threats persisted against journalists, who investigated or exposed corruption or other government misdeeds.[43][44] The US-based Committee to Protect Journalists concluded in 2007 that these attacks, and police reluctance in some cases to pursue the perpetrators, were "helping to foster an atmosphere of impunity against independent journalists."[45][46] Media watchdogs have stated attacks and pressure on journalists have increased since the February 2010 election of Viktor Yanukovych as President.[47]

In December 2009, and during the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election, campaign incumbent Prime Minister of Ukraine and presidential candidate[48] Yulia Tymoshenko complained Ukrainian TV channels are manipulating the consciousness of citizens in favor of financial and oligarchic groups.[49] As of January 2009, Ukrainian Prime Minister, Yulia Tymoshenko refused to appear in Inter TV-programmes "until journalists, management and owners of the TV channel stop destroying the freedom of speech and until they remember the essence of their profession - honesty, objectiveness, and unbiased stand".[50]

Yanukovych presidency (2010-2013)

Since Viktor Yanukovych was elected President of Ukraine in February 2010 Ukrainian journalists and international journalistic watchdogs (including the European Federation of Journalists and Reporters Without Borders) have complained about a deterioration of press freedom in Ukraine.[51][52][53][54] Yanukovych responded (in May 2010) that he "deeply values press freedom" and that "free, independent media that must ensure society's unimpeded access to information".[51] Anonymous journalists stated early May 2010 that they were voluntarily tailoring their coverage so as not to offend the Yanukovych administration and the Azarov Government.[55] The Azarov Government denies censoring the media,[56] so did the Presidential Administration[57] and President Yanukovych himself.[58] Presidential Administration Deputy Head Hanna Herman stated on 13 May 2010 that the opposition benefited from discussions about the freedom of the press in Ukraine and also suggested that the recent reaction of foreign journalists organizations had been provoked by the opposition.[57] On 12 May 2010, the parliamentary committee for freedom of speech and information called on the General Prosecutor's Office to immediately investigate complaints by journalists of pressure on journalists and censorship.[59] Also in May 2010 the Stop Censorship movement was founded by more than 500 journalist.[60]

A law on strengthening the protection of the ownership of mass media offices, publishing houses, bookshops and distributors, as well as creative unions was passed by the Ukrainian Parliament on 20 May 2010.[61]

Since the February 2010 election of Viktor Yanukovych as President Media watchdogs have stated attacks and pressure on journalists have increased.[47] The International Press Institute addressed an open letter to President Yanukovych on 10 August 2010 urging him to address what the organisation saw as a disturbing deterioration in press freedom over the previous six months in Ukraine.[62] PACE rapporteur Renate Wohlwend noticed on 6 October 2010 that "Some progress had been made in recent years but there had also been some retrograde steps".[63] In January 2011 Freedom House stated it had perceived "negative trends in Ukraine" during 2010; these included: curbs on press freedom, the intimidation of civil society, and greater government influence on the judiciary.[5]

According to the US Department of State in 2009 there were no attempts by central authorities to direct media content, but there were reports of intimidation of journalists by national and local officials.[40] Media at times demonstrated a tendency toward self‑censorship on matters that the government deemed sensitive.[40][41] Stories in the electronic and printed media (veiled advertisements and positive coverage presented as news) and participation in a television talk show can be bought.[40] Media watchdog groups have express concern over the extremely high monetary damages that were demanded in court cases concerning libel.[40]

In 2013 there were concerns over the corrupting influence of certain political figures, connected to the government of Viktor Yanukovych on Ukrainian media.[64]

Euromaidan revolution and Poroshenko presidency (2014-2019)

A May 2014 report from the OSCE found approximately 300 instances of perceived violent attacks on the media in Ukraine since November 2013.[65] The Ukrainian NGO Institute of Mass Information recorded at least 995 violations of free speech in 2014 - the double than in 2013 (496) and triple than in 2012 (324). Most attacks on journalists happened during the euromaidan period in Kyiv (82 in January, 70 in February 2014). 78 journalists were abducted and illegally detained by various groups in 2014 - a new category of professional risk; 20 such cases happened in Donetsk in April 2014. In 2014 restrictions to press freedom in Ukraine included police impeding access to public buildings, physical attacks on press rooms, and cyberattacks (e.g. against the Glavnoe, Gordon and UNIAN websites); in July 2014 a firebomb was thrown at the TV channel 112 Ukraine.[6]

Political interference in the media sector greatly diminished after the flight of Yanukovych from Ukraine, with media outlets almost immediately starting to openly discuss the events of the previous months, including the moments of violence, which had previously been censored or self-censored through pressures on owners and managers. The 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election was covered with a wide variety of political orientations in the media.[6] Minor cases of pressures or censorship attempts were reported in 2014 too. In Kirovohrad in December 2014 a regional politician ordered a subordinate to review the Zorya newspaper before its publication.[6]

Censorship issues were debated in 2015 concerning aggressive propaganda from Russian state-owned news outlets to support the Russian annexation of Crimea, encourage separatism in Donbas and discredit the Kyiv government.[6] Creating some concern among Western human rights monitors was that under the impact of war and perceived extreme social polarization the Ukrainian government has been accused of cracking down on pro-separatist points of view.[66] For example, Ukraine also shut down most Russia-based television stations on the grounds that they purvey "propaganda," and barred a growing list of Russian journalists from entering the country.[66][67][6][68][69][70][71][72][nb 1]

The Ministry of Information Policy was established on 2 December 2014.[74][75] The ministry oversees information policy in Ukraine. According to the first Minister of Information, Yuriy Stets, one of the goals of its formation was to counteract "Russian information aggression" amidst pro-Russian unrest across Ukraine, and the ongoing war in the Donbas region.[75][76] Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko said that the main function of the ministry is to stop "the spreading of biased information about Ukraine".[77]

On 16 May 2017 president Poroshenko signed a decree banning various Russian internet service providers and news sources, among others, VKontakte, Odnoklassniki, Yandex, Rossiya Segodnya, RBC, VGTRK, but also a number of independent stations such as the RBC, claiming this was done for "security reasons".[78][79] Tanya Cooper from Human Rights Watch called the decree: "a cynical, politically expedient attack on the right to information affecting millions of Ukrainians, and their personal and professional lives".[71] Reporters Without Borders (RSF) also condemned the ban imposed on Russian social networks.[80]

Since November 2015 Ukrainian authorities, state agencies and local government authorities are forbidden to act as founders (or cofounders) of printed media outlets.[81]

Freedom House reported the status of press freedom in Ukraine in 2015 as improving from Not Free to Partly Free. It justified the change as follows:[6]

due to profound changes in the media environment after the fall of President Viktor Yanukovych's government in February, despite a rise in attacks on journalists during the Euromaidan protests of early 2014 and the subsequent conflict in eastern Ukraine. The level of government hostility and legal pressure faced by journalists decreased, as did political pressure on state-owned outlets. The media also benefited from improvements to the law on access to information and the increased independence of the broadcasting regulator.

In 2015 the main concerns about media freedom in Ukraine concern the handling of pro-Russian propaganda, the concentration of media ownership, and the high risks of violence against journalists, especially in the conflict areas in the east.[6] In September 2015 Freedom House classified the Internet in Ukraine as "partly free" and the press as "partly free".[13] Ukraine was in 102nd place out of 180 countries listed in the 2017 World Press Freedom Index.[80] In 2017 organizations like Reporters Without Borders, Human Rights Watch and Committee to Protect Journalists condemned then Poroshenko's government recent bans on media.[82][71][83][84]

Russian invasion and Zelensky presidency (2019-present)

On March 3, 2022, the Criminal Code of Ukraine was supplemented by Article 436-2, titled "Justification, recognition as legitimate, denial of the armed aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, glorification of its participants". The article, which has been criticized by the OHCHR and other human rights groups,[85][86] states punishment by correctional labor up to two years or imprisonment up to eight years for such speech.[87] Gonzalo Lira, an American pro-Russia blogger living in Ukraine, was among those arrested under this law.[88]

On December 30, 2022, President Volodymyr Zelensky signed into law a bill that would expand the power of government to regulate media outlets and journalists in the country, over the objections of journalists and international press freedom groups.[89][90]

According to a State Department report published in 2023 restrictions were placed on media freedoms enabling "an unprecedented level of control over primetime television news." Some speakers who criticised the government were blacklisted from government-directed news. The outlets and journalists who were considered a threat to the national security and who undermined the country's sovereignty and territorial integrity according to the authorities were blocked, banned or sanctioned.[91]

Press freedom scores as perceived by Freedom House

The following table shows press freedom scores calculated each year by a foreign non-governmental organisation called Freedom House. The year is the year of issue, and data relate to the previous year.

- Score 0–30 = press were free.[92]

- Score 31–60 = press were partly free.[92]

- Score 61–100 = press were not free.[92]

| Year | UK | USA | Estonia | Lithuania | Latvia | Ukraine | Moldova | Georgia | Belarus | Russia | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 24 | 12 | 28 | 30 | 29 | 44 | 41 | 73 | 66 | 40 | [92] |

| 1995 | 22 | 12 | 25 | 29 | 29 | 42 | 47 | 70 | 67 | 55 | [92] |

| 1996 | 22 | 14 | 24 | 25 | 21 | 39 | 62 | 68 | 70 | 58 | [92] |

| 1997 | 22 | 14 | 22 | 20 | 21 | 49 | 57 | 55 | 85 | 53 | [92] |

| 1998 | 21 | 12 | 20 | 17 | 21 | 49 | 58 | 56 | 90 | 53 | [92] |

| 1999 | 20 | 13 | 20 | 18 | 21 | 50 | 56 | 57 | 80 | 59 | [92] |

| 2000 | 20 | 13 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 60 | 58 | 47 | 80 | 60 | [92] |

| 2001 | 17 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 60 | 59 | 53 | 80 | 60 | [92] |

| 2002 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 60 | 59 | 53 | 82 | 60 | [92] |

| 2003 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 67 | 59 | 54 | 82 | 66 | [92] |

| 2004 | 19 | 13 | 17 | 18 | 17 | 68 | 63 | 54 | 84 | 67 | [92] |

| 2005 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 17 | 59 | 65 | 56 | 86 | 68 | [92] |

| 2006 | 19 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 53 | 65 | 56 | 88 | 72 | [92] |

| 2007 | 19 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 53 | 65 | 57 | 89 | 75 | [92] |

| 2008 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 18 | 22 | 53 | 66 | 60 | 91 | 78 | [92] |

| 2009 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 18 | 23 | 55 | 67 | 60 | 91 | 80 | [92] |

| 2010 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 21 | 26 | 53 | 65 | 59 | 92 | 81 | [92] |

| 2011 | 19 | 17 | 18 | 22 | 26 | 56 | 55 | 55 | 93 | 81 | [92] |

| 2012 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 23 | 27 | 59 | Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Freedom_of_the_press_in_Ukraine