A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Health care services in Nepal are provided by both public and private sectors and are generally regarded as failing to meet international standards. Prevalence of disease is significantly higher in Nepal than in other South Asian countries, especially in rural areas.[1][2] Moreover, the country's topographical and sociological diversity results in periodic epidemics of infectious diseases, epizootics and natural hazards such as floods, forest fires, landslides, and earthquakes.[2] But, recent surge in Non communicable diseases has emerged as the main public health concern and this accounts for more than two-thirds of total mortality in country. A large section of the population, particularly those living in rural poverty, are at risk of infection and mortality by communicable diseases, malnutrition and other health-related events.[2] Nevertheless, some improvements in health care can be witnessed; most notably, there has been significant improvement in the field of maternal health. These improvements include:[3]

- Human Development Index (HDI) value increased to 0.602 in 2019[4] from 0.291 in 1975.[5][6]

- Mortality rate during childbirth deceased from 850 out of 100,000 mothers in 1990 to 186 out of 100,000 mothers in 2017.[7]

- Mortality under the age of five decreased from 61.5 per 1,000 live births in 2005 to 32.2 per 1,000 live births in 2018.[7]

- Infant Mortality decreased from 97.70 in 1990 to 26.7 in 2017.[7]

- Neonatal Mortality decreased from 40.4 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2000 to 19.9 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2018.[7]

- Child malnutrition: Stunting 37%, wasting 11%, and underweight 30% among children under the age of five.[8]

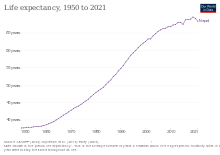

- Life expectancy rose from 66 years in 2005 to 71.5 years in 2018.[9][10]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[11] finds that Nepal is fulfilling 85.7% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to health based on its level of income.[12] When looking at the right to health with respect to children, Nepal achieves 97.1% of what is expected based on its current income.[12] In regards to the right to health amongst the adult population, the country achieves 94.6% of what is expected based on the nation's level of income.[12] Nepal falls into the "very bad" category when evaluating the right to reproductive health because the nation is fulfilling only 65.5% of what the nation is expected to achieve based on the resources (income) it has available.[12]

Health care expenditure

In 2002, government funding for healthcare was approximately US$2.30 per person. Approximately 70% of health expenditure came from out-of-pocket contributions. Government allocation for health care was approximately 7.45% of the budget in 2021.[13] In 2012, the Nepalese government launched a pilot program for universal health insurance in five districts of the country.[14]

As of 2014, Nepal's total expenditure on health per capita was US$137.[15]

Health care infrastructure

There are 125 Hospitals in Nepal according to the data up to 2019. Health care services, hygiene, nutrition, and sanitation in Nepal are of inferior quality and fail to reach a large proportion of the population, particularly in rural areas.[16] The poor have limited access to basic health care due to high costs, low availability, lack of health education and conflicting traditional beliefs.[17] Reproductive health care is limited and difficult to access for women. The United Nation's 2009 human development report highlighted a growing social concern in Nepal in the form of individuals without citizenship being marginalized and denied access to government welfare benefits.[18][19][20]

These problems have led many governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to implement communication programs encouraging people to engage in healthy behavior such as family planning, contraceptive use, spousal communication, and safe motherhood practices, such as the use of skilled birth attendants during delivery and immediate breastfeeding.[21]

Micro-nutrient deficiencies are widespread, with almost half of pregnant women and children under five, as well as 35% of women of reproductive age, being anemic. Only 24% of children consume iron-rich food, 24% of children meet a minimally acceptable diet, and only half of the pregnant women take recommended iron supplementation during pregnancy. A contributing factor to deteriorating nutrition is high diarrhoeal disease morbidity, exacerbated by the lack of access to proper sanitation and the common practice of open defecation (44%) in Nepal.[22]

Nutrition of children under 5 years

Source:[23]

Periods of stagnant economic growth and political instability have contributed to acute food shortages and high rates of malnutrition, mostly affecting vulnerable women and children in the hills and mountains of the mid and far western regions. Despite the rate of individuals with stunted growth and the number of cases of underweight individuals has decreased, alongside an increase of exclusive breastfeeding in the past seven years, 41% of children under the age of five still suffer from stunted growth, a rate that increases to 60% in the western mountains. A report from DHS 2016, has shown that in Nepal, 36% of children are stunted (below −2 standard deviation), 12% are severely stunted (below −3 standard deviation), 27% of children under 5 are underweight, and 5% are severely underweight. Variation in the percentage of stunted and underweight children under 5 can be compared between urban and rural regions of Nepal, with rural areas being more affected (40% stunted and 31% underweight) than urban areas (32% stunted and 23% underweight). There is positive association between household food consumption scores and lower prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting. Children in a secure food household have the lowest rates of stunting (33%), while children in an insecure food household have the highest rates (49%). Similarly, maternal education has an inverse relationship with childhood stunting. In addition, underweight and stunting issues are also inversely correlated to their equity possessions. Children in the lowest wealth quintile are more stunted (49%) and underweight (33%) than children in the highest quintile (17% stunted and 12% underweight).[24]

The nutritional status of children in Nepal has improved over the last two decades. Decreasing trends of children having stunted growth and being underweight have been observed since 2001. The percentage of stunted children in Nepal was 14% between 2001 and 2006, 16% between 2006 and 2011, and 12% between 2011 and 2016.[24] A similar trend can also be observed for underweight children. These trends demonstrate progress towards the achievement of the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) target. However, there is still a long way to go to meet the SDG target of reducing stunting to 31% and underweight to 25% among children under 5 by 2017 (National Planning Commission 2015).[citation needed]

Micro-nutrient deficiencies are widespread, with almost half of pregnant women and children under five, as well as 35% of women of reproductive age, being anemic. Only 24% of children consume iron-rich food, 24% of children meet a minimally acceptable diet, and only half of the pregnant women take recommended iron supplementation during pregnancy. A contributing factor to deteriorating nutrition is high diarrheal disease morbidity, exacerbated by the lack of access to proper sanitation and the common practice of open defecation (44%) in Nepal.[22]

| Urban areas | Rural areas | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stunted | 27% | 42% | 41% |

| Wasted | 8% | 11% | 11% |

| Underweight | 17% | 30% | 29% |

Geographical constraints

Much of rural Nepal is located in hilly or mountainous regions. Nepal's rugged terrain and the lack of properly enabling infrastructure make it highly inaccessible, limiting the availability of basic health care in many rural mountain areas.[25] In many villages, the only mode of transportation is by foot. This results in a delay of treatment, which can be detrimental to patients in need of immediate medical attention.[26] Most of Nepal's health care facilities are concentrated in urban areas. Rural health facilities often lack adequate funding.[27]

In 2003, Nepal had 10 health centers, 83 hospitals, 700 health posts, and 3,158 "sub-health posts," which serve villages. In addition, there were 1,259 physicians, one for every 18,400 persons.[28] In 2000, government funding for health matters was approximately US$2.30 per person and approximately 70% of health expenditure came from contributions. Government allocations for health were around 5.1% of the budget for the 2004 fiscal year, and foreign donors provided around 30% of the total budget for health expenditure.[5]

Political influences

Nepal's health care issues are largely attributed to its political power and resources being mostly centered in its capital, Kathmandu, resulting in the social exclusion of other parts of Nepal. The restoration of democracy in 1990 has allowed the strengthening of local institutions. The 1999 Local Self Governance Act aimed to include devolution of basic services such as health, drinking water, and rural infrastructure but the program has not provided notable public health improvements. Due to a lack of political will,[29] Nepal has failed to achieve complete decentralization, thus limiting its political, social and physical potential.[18]

Health status

Life expectancy

In 2010, the average Nepalese lived to 65.8 years. According to the latest WHO data published in 2012, life expectancy in Nepal is 68. Life expectancy at birth for both sexes increased by 6 years over the year 2010 and 2012. In 2012, healthy expectancy in both sexes was 9-year(s) lower than overall life expectancy at birth. This lost healthy life expectancy represents 9 equivalent year(s) of full health lost through years lived with morbidity and disability.[9]

Disease burden

Disease burden or burden of disease is a concept used to describe the death and loss of health due to diseases, injuries and risk factors.[30] One most common measure used to measure the disease burden is disability adjusted life year (DALY). Developed in 1993, the indicator is a health gap measure and simply the sum of years lost due to premature death and years lived with disability.[31] One DALY represents a loss of one year of healthy life.[32]

Trend analysis

DALYs of Nepal has shown to be dropping down since 1990 but it is still high compared to the global average. Fig 1 shows that the 69,623.23 DALYs lost per 100,000 individuals in Nepal in 1990 has decreased to almost half (34,963.12 DALYs) in 2017. This is close to the global average of 32,796.89 DALYs lost.[32]

Disease burden by cause

Dividing the diseases in three common groups of communicable diseases, non- communicable disease (NCD) and injuries (also includes violence, suicides, etc.), a large shift from communicable disease to NCDs can be seen from 1990 to 2017. NCDs has a share of 58.67% of total DALYs lost in 2017 which was only 22.53% in 1990 [32] (refer fig 2)

Below is the table showing how the causes of DALYs lost has changed from 1990 to 2019 [33]

| S.N | 1990 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Respiratory infections & TB | Cardiovascular diseases |

| 2 | Maternal and neonatal causes | Maternal and neonatal causes |

| 3 | Other infections | Chronic respiratory illness |

| 4 | Enteric infections | Respiratory infections & TB |

| 5 | Nutritional deficiencies | Neoplasms |

| 6 | Cardiovascular diseases | Mental disorders |

| 7 | Others NCDs | Musculoskeletal disorders |

| 8 | Unintentional injuries | Other NCDs |

| 9 | Chronic respiratory illness | Unintentional injuries |

| 10 | Digestive diseases | Digestive diseases |

According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017, the eight leading causes of morbidity (illness) and mortality (death) in Nepal are: Neonatal disorders[34] (9.97%), Ischaemic Heart Disease (7.55%), COPD (5.35%), Lower respiratory infection (5.15%), Diarrhoeal disease (3.42%), Road injury[35] (3.56%), Stroke (3.49%), Diabetes (2.35%).[36] The chart (Fig 3) shows the burden of disease prevalence in Nepal over a period of time. Diseases like neonatal disorder, lower respiratory tract infection, and diarrhoeal diseases have shown a gradual decrease in prevalence over the period from 1990 to 2017. The reason for this decrease in number is due to the implementation of several health programs by the government with the involvement of other international organizations such as WHO and UNICEF for maternal and child health, as these diseases are very common among the children. Whereas, there is a remarkable increment in the number of other diseases like Ischemic heart disease (IHD), Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Road injuries, Stroke, and Diabetes.

Ischemic heart disease

Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) is gradually emerging as one of the major health challenges in Nepal. It is the most common type of heart disease and cause of heart attacks. The rapid change in lifestyle, unhealthy habits (smoking, sedentary lifestyle etc.), and economic development are considered to be responsible for the increase. Despite a decrease in Ischemic Heart Disease mortality in developed countries, substantial increases have been experienced in developing countries like Nepal. IHD is the number one cause of death in adults from both low and middle-income countries as well as from high-income countries. The incidence of IHD is expected to increase by approximately 29% in women and 48% in men in the developed countries between 1990 and 2020.

A total of 182,751 deaths are estimated in Nepal for the year 2017. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading causes of death – two-thirds (66%) of deaths are due to NCDs, with an additional 9% due to injuries. The remaining 25% are due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional (CMNN) diseases. Ischemic heart disease (16.4% of total deaths), Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (9.8% of total deaths), Diarrheal diseases (5.6% of total deaths), Lower respiratory infections (5.1% of total deaths), and Intracerebral hemorrhage (3.8% of total deaths), were the top five causes of death in 2017[37]

Ischemic Heart Disease is second burden of disease and the leading cause of death in Nepal for the last 16 years, starting from 2002. Death due to IHD is increasing an alarming rate in Nepal from 65.82 to 100.45 death per 100,000 from 2002 to 2017.[38] So, the large number of epidemiological research is necessary to determine the incidence & prevalence of IHD in Nepal and to identify the magnitude of the problem so that timely primary and secondary prevention can be done. As it is highly preventable and many risk factor are related to our lifestyle like; smoking, obesity, unhealthy diet, etc. So, knowledge and awareness regarding these risk factors are important in the prevention of IHD. Shahid Gangalal National Heart Center conducted a cardiac camp in different parts of Nepal from September 2008 to July 2011. The prevalence of heart disease was found higher in urban areas than rural areas where hypertension claims the major portion. The huge proportion of hypertension in every camp suggests that Nepal is in daring need of preventive programs of heart disease to prevent the catastrophic effect of IHD in near future. Also, according to this study the proportion of IHD ranges from 0.56% (Tikapur) to 15.12% (Birgunj) in Nepal.[39]

Among WHO region in the European region, African region, Region of the Americas and Eastern Mediterranean death rate is in decreasing trend while in Western Pacific, South East Asia it is increasing.

[38] Table 1: Comparison of Death per 100,000 due to Ischemic Heart Disease Between Nepal, Global and 6 WHO Region

| Year | Global | Nepal | European Region | African Region | Western Pacific Region | South East Asia Region | Region of the America | Eastern Mediterranean |

| 1990 | 108,72 | 62,72 | 270,32 | 46,77 | 57,29 | 69,11 | 142,27 | 117,37 |

| 2004 | 108,33 | 69,05 | 278,53 | 45,53 | 77,75 | 74 | 114,73 | 114,51 |

| 2010 | 111,15 | 85,32 | 255,58 | 41,26 | 97,39 | 90,74 | 105,73 | 109,89 |

| 2017 | 116,88 | 100,45 | 245,3 | 39,26 | 115,94 | 103,47 | 111,91 | 112,63 |

Distribution according to age and sex :

Incidence of IHD occurs in men between 35 and 45 years age. After the age of 65 the incidence of men and women equalizes, although there is evidence suggesting that more women are being seen with IHD earlier because of increased stress, smoking and menopause. The risk of IHD increases as age increases. Middle-aged adults are mostly affected by IHD. For men, the risk starts to climb at about age 45, and by age 55, the risk becomes double. It continues to increase until, by age 85. For women, the risk of IHD also climbs with age, but the trend begins about 10 years later than in men and especially with the onset of menopause.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (Nepali: क्षयरोग), the world's most serious public health problem is an infectious bacterial disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium.[40] Although most common Mycobacterium species which causes tuberculosis is M. tuberculosis, TB is also caused by M. bovis and M. africanum and occasionally by opportunistic Mycobacteria which are: M. Kansaii, M. malmoense, M. simiae, M. szulgai, M. xenopi, M. avium-intracellulare, M. scrofulacum, and M. chelonei.[41]

Tuberculosis is the most common cause of death due to single organism among person over 5 years of age in low-income countries. In addition, 80% of deaths due to tuberculosis occurs in young to middle age men and women.[42] The incidence of disease in a community may be affected by many factors, including the density of population, the extent of overcrowding and the general standard of living and health care. Certain groups like refugees, HIV infected, person with physical and psychological stress, nursing home residents and impoverished have high risk to develop TB.[43]

The goal 3.3 within the goal 3 of Sustainable Development Goals states "end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases" and the targets linked to the end TB strategy are:

- Detect 100% of new sputum smear-positive TB cases and cure at least 85% of these cases.

- Eliminate TB as a public health problem (<1 case per million population) by 2050.[44]

In Nepal, 45% of the total population is infected with TB, out of which 60% are in the productive age group (15–45). Former Director of National Tuberculosis Center Dr. Kedar Narsingh KC stated that among an estimated 40,000 new TB patients every year, only around 25,000 visit health facilities.[45] According to national TB prevalence survey around 69,000 people developed TB in 2018. In addition, 117,000 people are living with the disease in Nepal.[46]

| Age Group | Male (%) | Female (%) | % | |

| 10–14 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | |

| 15–19 | 8.8 | 15.8 | 10.8 | |

| 20–24 | 16.6 | 20.1 | 17.6 | |

| 25–29 | 15.8 | 10.8 | 14.4 | |

| 30–34 | 9.8 | 14.0 | 11 | |

| 35–39 | 10.6 | 9.3 | 10.3 | |

| 40–44 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 8.7 | |

| 45–49 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 7.7 | |

| 50–54 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 8.3 | |

| 55–59 | 8.1 | 5.4 | 7.3 | |

| 60–64 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | |

| 65 and above | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| Not mentioned | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

There are 624 microscopy centers registered whereas the National TB Reference Laboratories, National tuberculosis centre and GENETUP perform culture and drug susceptibility testing service in Nepal.[48]

National Tuberculosis control program (NTP) employs directly observed treatment strategy (DOTS). In 1995, World Health Organization recommended DOTS as one of the most cost effective strategies available for tuberculosis control. DOTS is the strategy for improving treatment outcome by giving drugs to the patients under direct observation of health workers. DOTS has been found to be 100% effective for tuberculosis control. There are around 4323 TB treatment centers in Nepal.[48] Although introduction of DOTS has already reduced the numbers of deaths, however 5,000 to 7,000 people still continue to die each year.[49]

The burden of drug resistance tuberculosis is estimated at 1500 (0.84 to 2.4) cases annually. But only 350 to 450 Multidrug resistance TB are reported yearly. So, in NTP's strategic plan 2016–2021, the main objective is to diagnose 100% of the MDR TB by 2021 and to successfully treat a minimum 75% of those cases.[48]

HIV/AIDS

Making up approximately 8.1% of the total estimated population of 40,723, there were about 3,282 children aged 14 years or younger living with HIV in Nepal in 2013. There are 3,385 infections estimated among the population aged 50 years and above (8.3% of the total population). By sex, males account for two‐thirds (66%) of the infections and the remaining, more than one‐third (34%) of infections are in females, out of which around 92.2% are in the reproductive age group of 15‐49 years. The male to female sex ratio of total infection decreased from 2.15 in 2006 to 1.95 in 2013 and is projected to be 1.86 by 2020.[50] The epidemic in Nepal is driven by injecting drug users, migrants, sex workers & their clients and MSM. Results from the 2007 Integrated Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Study (IBBS) among IDUs in Kathmandu, Pokhara, and East and West Terai indicate that the highest prevalence rates have been found among urban IDUs, 6.8% to 34.7% of whom are HIV-positive, depending on location. In terms of absolute numbers, Nepal's 1.5 million to 2 million labor migrants account for the majority of Nepal's HIV-positive population. In one subgroup, 2.8% of migrants returning from Mumbai, India, were infected with HIV, according to the 2006 IBBS among migrants.[51]

As of 2007, HIV prevalence among female sex workers and their clients was less than 2% and 1%, respectively, and 3.3% among urban-based MSM. HIV infections are more common among men than women, as well as in urban areas and the far western region of Nepal, where migrant labor is more common. Labor migrants make up 41% of the total known HIV infections in Nepal, followed by clients of sex workers (15.5 percent) and IDUs (10.2 percent).[51]

Diarrhoeal diseases

Diarrhoeal disease is one of the leading causes of death globally which is mainly caused by bacterial, viral or parasitic organisms. In addition, the other factors include malnutrition, contaminated water and food sources, animal faeces, and person-to-person transmission due to poor hygienic conditions. Diarrhoea is an indication of intestinal tract infection which is characterized by the passage of loose or liquid stool three or more times a day, or more than a normal passage per day. This disease can be prevented by action of several measures including access to contamination-free water and food sources, hand washes with soap and water, personal hygiene and sanitation, breastfeeding the child for at least six months of life, vaccination against Rotavirus and general awareness among the people. Treatment is performed by rehydration with oral rehydration salt (ORS) solution, use of zinc supplements, administration of intravenous fluid in case of severe dehydration or shock, and the continuing supply of nutrient-rich food, especially to malnourished children.[52]

Global Burden of Disease Study shows that diarrhoeal diseases account for 5.91% of total deaths among all age groups of Nepal in 2017. In the same year, the data indicates that diarrhoeal diseases has the highest cause of death of 9.14% in the age group 5–14 years followed by 8.91% deaths in 70+ age group.[53]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Health_in_Nepal

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.