A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Iroquois Confederacy Haudenosaunee | |

|---|---|

Map showing historical (in purple) and currently recognized (in pink) Iroquois territorial claims | |

| Status | Recognized confederation, later became an unrecognized government[1][2] |

| Capital | Onondaga (village), Onondaga Nation (at various modern locations:

|

| Common languages | Iroquoian languages |

| Government | Confederation |

| Legislature | Grand Council of the Six Nations |

| History | |

• Established | Between 1450 and 1660 (estimate) |

The Iroquois (/ˈɪrəkwɔɪ, -kwɑː/ IRR-ə-kwoy, -kwah), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the endonym Haudenosaunee (/ˌhoʊdɪnoʊˈʃoʊni/ HOH-din-oh-SHOH-nee;[3] lit. 'people who are building the longhouse') are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of Native Americans and First Nations peoples in northeast North America. They were known by the French during the colonial years as the Iroquois League, and later as the Iroquois Confederacy, while the English simply called them the "Five Nations". The peoples of the Iroquois included (from east to west) the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. After 1722, the Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora people from the southeast were accepted into the confederacy, from which point it was known as the "Six Nations".

The Confederacy likely came about between the years 1450 CE and 1660 CE as a result of the Great Law of Peace, said to have been composed by the Deganawidah the Great Peacemaker, Hiawatha, and Jigonsaseh the Mother of Nations. For nearly 200 years, the Six Nations/Haudenosaunee Confederacy were a powerful factor in North American colonial policy, with some scholars arguing for the concept of the Middle Ground,[4] in that European powers were used by the Iroquois just as much as Europeans used them.[5] At its peak around 1700, Iroquois power extended from what is today New York State, north into present-day Ontario and Quebec along the lower Great Lakes–upper St. Lawrence, and south on both sides of the Allegheny mountains into present-day Virginia and Kentucky and into the Ohio Valley.

The St. Lawrence Iroquoians, Wendat (Huron), Erie, and Susquehannock, all independent peoples known to the European colonists, also spoke Iroquoian languages. They are considered Iroquoian in a larger cultural sense, all being descended from the Proto-Iroquoian people and language. Historically, however, they were competitors and enemies of the Iroquois Confederacy nations.[6]

In 2010, more than 45,000 enrolled Six Nations people lived in Canada, and over 81,000 in the United States.[7][8]

Names

Haudenosaunee ("People of the Longhouse") is the autonym by which the Six Nations refer to themselves.[9] While its exact etymology is debated, the term Iroquois is of colonial origin. Some scholars of Native American history consider "Iroquois" a derogatory name adopted from the traditional enemies of the Haudenosaunee.[10] A less common, older autonym for the confederation is Ongweh’onweh, meaning "original people".[11][12][13]

Haudenosaunee derives from two phonetically similar but etymologically distinct words in the Seneca language: Hodínöhšö:ni:h, meaning "those of the extended house", and Hodínöhsö:ni:h, meaning "house builders".[14][15][16] The name "Haudenosaunee" first appears in English in Lewis Henry Morgan's work (1851), where he writes it as Ho-dé-no-sau-nee. The spelling "Hotinnonsionni" is also attested from later in the nineteenth century.[14][17] An alternative designation, Ganonsyoni, is occasionally encountered as well,[18] from the Mohawk kanǫhsyǫ́·ni "the extended house", or from a cognate expression in a related Iroquoian language; in earlier sources it is variously spelled "Kanosoni", "akwanoschioni", "Aquanuschioni", "Cannassoone", "Canossoone", "Ke-nunctioni", or "Konossioni".[14] More transparently, the Haudenosaunee confederacy is often referred to as the Six Nations (or, for the period before the entry of the Tuscarora in 1722, the Five Nations).[14][a] The word is Rotinonshón:ni in the Mohawk language.[19]

The origins of the name Iroquois are somewhat obscure, although the term has historically been more common among English texts than Haudenosaunee. Its first written appearance as "Irocois" is in Samuel de Champlain's account of his journey to Tadoussac in 1603.[20] Other early French spellings include "Erocoise", "Hiroquois", "Hyroquoise", "Irecoies", "Iriquois", "Iroquaes", "Irroquois", and "Yroquois",[14] pronounced at the time as or .[b] Competing theories have been proposed for this term's origin, but none have gained widespread acceptance. By 1978 Ives Goddard wrote: "No such form is attested in any Indian language as a name for any Iroquoian group, and the ultimate origin and meaning of the name are unknown."[14]

Jesuit priest and missionary Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix wrote in 1744:

The name Iroquois is purely French, and is formed from the term Hiro or Hero, which means I have said—with which these Indians close all their addresses, as the Latins did of old with their dixi—and of Koué, which is a cry sometimes of sadness, when it is prolonged, and sometimes of joy, when it is pronounced shorter.[20]

In 1883, Horatio Hale wrote that Charlevoix's etymology was dubious, and that "no other nation or tribe of which we have any knowledge has ever borne a name composed in this whimsical fashion".[20] Hale suggested instead that the term came from Huron, and was cognate with the Mohawk ierokwa "they who smoke", or Cayuga iakwai "a bear". In 1888, J. N. B. Hewitt expressed doubts that either of those words exist in the respective languages. He preferred the etymology from Montagnais irin "true, real" and ako "snake", plus the French -ois suffix. Later he revised this to Algonquin Iriⁿakhoiw as the origin.[20][21]

A more modern etymology was advocated by Gordon M. Day in 1968, elaborating upon Charles Arnaud from 1880. Arnaud had claimed that the word came from Montagnais irnokué, meaning "terrible man", via the reduced form irokue. Day proposed a hypothetical Montagnais phrase irno kwédač, meaning "a man, an Iroquois", as the origin of this term. For the first element irno, Day cites cognates from other attested Montagnais dialects: irinou, iriniȣ, and ilnu; and for the second element kwédač, he suggests a relation to kouetakiou, kȣetat-chiȣin, and goéṭètjg – names used by neighboring Algonquian tribes to refer to the Iroquois, Huron, and Laurentian peoples.[20]

The Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America attests the origin of Iroquois to Iroqu, Algonquian for "rattlesnake".[22] The French encountered the Algonquian-speaking tribes first, and would have learned the Algonquian names for their Iroquois competitors.

Confederacy

The Iroquois Confederacy is believed to have been founded by the Great Peacemaker at an unknown date estimated between 1450 and 1660, bringing together five distinct nations in the southern Great Lakes area into "The Great League of Peace".[23] Other research, however, suggests the founding occurred in 1142.[24] Each nation within this Iroquoian confederacy had a distinct language, territory, and function in the League.

The League is governed by a Grand Council, an assembly of fifty chiefs or sachems, each representing a clan of a nation.[25]

When Europeans first arrived in North America, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois League to the French, Five Nations to the British) were based in what is now central and west New York State including the Finger Lakes region, occupying large areas north to the St. Lawrence River, east to Montreal and the Hudson River, and south into what is today northwestern Pennsylvania. At its peak around 1700, Iroquois power extended from what is today New York State, north into present-day Ontario and Quebec along the lower Great Lakes–upper St. Lawrence, and south on both sides of the Allegheny Mountains into present-day Virginia and Kentucky and into the Ohio Valley. From east to west, the League was composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations. In about 1722, the Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora joined the League, having migrated northwards from the Carolinas after a bloody conflict with white settlers. A shared cultural background with the Five Nations of the Iroquois (and a sponsorship from the Oneida) led the Tuscarora to becoming accepted as the sixth nation in the confederacy in 1722; the Iroquois become known afterwards as the Six Nations.[26][27]

Other independent Iroquoian-speaking peoples, such as the Erie, Susquehannock, Huron (Wendat) and Wyandot, lived at various times along the St. Lawrence River, and around the Great Lakes. In the American Southeast, the Cherokee were an Iroquoian-language people who had migrated to that area centuries before European contact. None of these were part of the Haudenosaunee League. Those on the borders of Haudenosaunee territory in the Great Lakes region competed and warred with the nations of the League.

French, Dutch, and English colonists, both in New France (Canada) and what became the Thirteen Colonies, recognized a need to gain favor with the Iroquois people, who occupied a significant portion of lands west of the colonial settlements. Their first relations were for fur trading, which became highly lucrative for both sides. The colonists also sought to establish friendly relations to secure their settlement borders.

For nearly 200 years, the Iroquois were a powerful factor in North American colonial policy. Alliance with the Iroquois offered political and strategic advantages to the European powers, but the Iroquois preserved considerable independence. Some of their people settled in mission villages along the St. Lawrence River, becoming more closely tied to the French. While they participated in French-led raids on Dutch and English colonial settlements, where some Mohawk and other Iroquois settled, in general the Iroquois resisted attacking their own peoples.

The Iroquois remained a large politically united Native American polity until the American Revolution, when the League was divided by their conflicting views on how to respond to requests for aid from the British Crown.[28] After their defeat, the British ceded Iroquois territory without consultation, and many Iroquois had to abandon their lands in the Mohawk Valley and elsewhere and relocate to the northern lands retained by the British. The Crown gave them land in compensation for the five million acres they had lost in the south, but it was not equivalent to earlier territory.

Modern scholars of the Iroquois distinguish between the League and the Confederacy.[29][30][31] According to this interpretation, the Iroquois League refers to the ceremonial and cultural institution embodied in the Grand Council, which still exists. The Iroquois Confederacy was the decentralized political and diplomatic entity that emerged in response to European colonization, which was dissolved after the British defeat in the American Revolutionary War.[29] Today's Iroquois/Six Nations people do not make any such distinction, use the terms interchangeably, but prefer the name Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

After the migration of a majority to Canada, the Iroquois remaining in New York were required to live mostly on reservations. In 1784, a total of 6,000 Iroquois faced 240,000 New Yorkers, with land-hungry New Englanders poised to migrate west. "Oneidas alone, who were only 600 strong, owned six million acres, or about 2.4 million hectares. Iroquoia was a land rush waiting to happen."[32] By the War of 1812, the Iroquois had lost control of considerable territory.

History

Historiography

Previous research, containing the discovery of Iroquois tools and artefacts, suggests that the origin of the Iroquois was in Montreal, Canada, near the St. Lawrence River. After an unsuccessful rebellion, they were driven out of Quebec to New York.

Knowledge of Iroquois history stem from Haudenosaunee oral tradition, archaeological evidence, accounts from Jesuit missionaries, and subsequent European historians. Historian Scott Stevens credits the early modern European value of written sources over oral tradition as contributing to a racialized, prejudiced perspective about the Iroquois through the 19th century.[33] The historiography of the Iroquois peoples is a topic of much debate, especially regarding the American colonial period.[34][35]

French Jesuit accounts of the Iroquois portrayed them as savages lacking government, law, letters, and religion.[36] But the Jesuits made considerable effort to study their languages and cultures, and some came to respect them. A source of confusion for European sources, coming from a patriarchal society, was the matrilineal kinship system of Iroquois society and the related power of women.[37] The Canadian historian D. Peter MacLeod wrote about the Canadian Iroquois and the French in the time of the Seven Years' War:

Most critically, the importance of clan mothers, who possessed considerable economic and political power within Canadian Iroquois communities, was blithely overlooked by patriarchal European scribes. Those references that do exist, show clan mothers meeting in council with their male counterparts to take decisions regarding war and peace and joining in delegations to confront the Onontio the Iroquois term for the French governor-general and the French leadership in Montreal, but only hint at the real influence wielded by these women.[37]

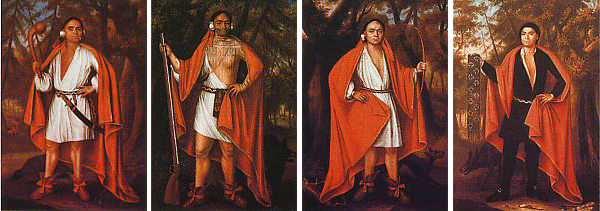

Eighteenth-century English historiography focuses on the diplomatic relations with the Iroquois, supplemented by such images as John Verelst's Four Mohawk Kings, and publications such as the Anglo-Iroquoian treaty proceedings printed by Benjamin Franklin.[38] A persistent 19th and 20th century narrative casts the Iroquois as "an expansive military and political power ... who subjugated their enemies by violent force and for almost two centuries acted as the fulcrum in the balance of power in colonial North America".[39]

Historian Scott Stevens noted that the Iroquois themselves began to influence the writing of their history in the 19th century, including Joseph Brant (Mohawk), and David Cusick (Tuscarora, c.1780–1840). John Arthur Gibson (Seneca, 1850–1912) was an important figure of his generation in recounting versions of Iroquois history in epics on the Peacemaker.[40] Notable women historians among the Iroquois emerged in the following decades, including Laura "Minnie" Kellogg (Oneida, 1880–1949) and Alice Lee Jemison (Seneca, 1901–1964).[41]

Formation of the League

The Iroquois League was established prior to European contact, with the banding together of five of the many Iroquoian peoples who had emerged south of the Great Lakes.[42][c] Many archaeologists and anthropologists believe that the League was formed about 1450,[43][44] though arguments have been made for an earlier date.[45] One theory argues that the League formed shortly after a solar eclipse on August 31, 1142, an event thought to be expressed in oral tradition about the League's origins.[46][47][48] Some sources link an early origin of the Iroquois confederacy to the adoption of corn as a staple crop.[49]

Anthropologist Dean Snow argues that the archaeological evidence does not support a date earlier than 1450. He has said that recent claims for a much earlier date "may be for contemporary political purposes".[50] Other scholars note that anthropological researchers consulted only male informants, thus losing the half of the historical story told in the distinct oral traditions of women.[51] For this reason, origin tales tend to emphasize the two men Deganawidah and Hiawatha, while the woman Jigonsaseh, who plays a prominent role in the female tradition, remains largely unknown.[51]

The founders of League are traditionally held to be Dekanawida the Great Peacemaker, Hiawatha, and Jigonhsasee the Mother of Nations, whose home acted as a sort of United Nations. They brought the Peacemaker's Great Law of Peace to the squabbling Iroquoian nations who were fighting, raiding, and feuding with each other and with other tribes, both Algonkian and Iroquoian. Five nations originally joined in the League, giving rise to the many historic references to "Five Nations of the Iroquois".[d][42] With the addition of the southern Tuscarora in the 18th century, these original five tribes still compose the Haudenosaunee in the early 21st century: the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca.

According to legend, an evil Onondaga chieftain named Tadodaho was the last converted to the ways of peace by The Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha. He was offered the position as the titular chair of the League's Council, representing the unity of all nations of the League.[52] This is said to have occurred at Onondaga Lake near present-day Syracuse, New York. The title Tadodaho is still used for the League's chair, the fiftieth chief who sits with the Onondaga in council.[53]

The Iroquois subsequently created a highly egalitarian society. One British colonial administrator declared in 1749 that the Iroquois had "such absolute Notions of Liberty that they allow no Kind of Superiority of one over another, and banish all Servitude from their Territories".[54] As raids between the member tribes ended and they directed warfare against competitors, the Iroquois increased in numbers while their rivals declined. The political cohesion of the Iroquois rapidly became one of the strongest forces in 17th- and 18th-century northeastern North America.

The League's Council of Fifty ruled on disputes and sought consensus. However, the confederacy did not speak for all five tribes, which continued to act independently and form their own war bands. Around 1678, the council began to exert more power in negotiations with the colonial governments of Pennsylvania and New York, and the Iroquois became very adroit at diplomacy, playing off the French against the British as individual tribes had earlier played the Swedes, Dutch, and English.[42]

Iroquoian-language peoples were involved in warfare and trading with nearby members of the Iroquois League.[42] The explorer Robert La Salle in the 17th century identified the Mosopelea as among the Ohio Valley peoples defeated by the Iroquois in the early 1670s.[55] The Erie and peoples of the upper Allegheny valley declined earlier during the Beaver Wars. By 1676 the power of the Susquehannock[e] was broken from the effects of three years of epidemic disease, war with the Iroquois, and frontier battles, as settlers took advantage of the weakened tribe.[42]

According to one theory of early Iroquois history, after becoming united in the League, the Iroquois invaded the Ohio River Valley in the territories that would become the eastern Ohio Country down as far as present-day Kentucky to seek additional hunting grounds. They displaced about 1,200 Siouan-speaking tribepeople of the Ohio River valley, such as the Quapaw (Akansea), Ofo (Mosopelea), and Tutelo and other closely related tribes out of the region. These tribes migrated to regions around the Mississippi River and the Piedmont regions of the east coast.[56]

Other Iroquoian-language peoples,[57] including the populous Wyandot (Huron), with related social organization and cultures, became extinct as tribes as a result of disease and war.[f] They did not join the League when invited and were much reduced after the Beaver Wars and high mortality from Eurasian infectious diseases. While the indigenous nations sometimes tried to remain neutral in the various colonial frontier wars, some also allied with Europeans, as in the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War. The Six Nations were split in their alliances between the French and British in that war.

Expansion

In Reflections in Bullough's Pond, historian Diana Muir argues that the pre-contact Iroquois were an imperialist, expansionist culture whose cultivation of the corn/beans/squash agricultural complex enabled them to support a large population. They made war primarily against neighboring Algonquian peoples. Muir uses archaeological data to argue that the Iroquois expansion onto Algonquian lands was checked by the Algonquian adoption of agriculture. This enabled them to support their own populations large enough to resist Iroquois conquest.[58] The People of the Confederacy dispute this historical interpretation, regarding the League of the Great Peace as the foundation of their heritage.[59]

The Iroquois may be the Kwedech described in the oral legends of the Mi'kmaq nation of Eastern Canada. These legends relate that the Mi'kmaq in the late pre-contact period had gradually driven their enemies – the Kwedech – westward across New Brunswick, and finally out of the Lower St. Lawrence River region. The Mi'kmaq named the last-conquered land Gespedeg or "last land", from which the French derived Gaspé. The "Kwedech" are generally considered to have been Iroquois, specifically the Mohawk; their expulsion from Gaspé by the Mi'kmaq has been estimated as occurring c. 1535–1600.[60][page needed]

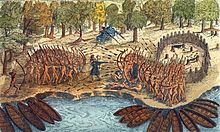

Around 1535, Jacques Cartier reported Iroquoian-speaking groups on the Gaspé peninsula and along the St. Lawrence River. Archeologists and anthropologists have defined the St. Lawrence Iroquoians as a distinct and separate group (and possibly several discrete groups), living in the villages of Hochelaga and others nearby (near present-day Montreal), which had been visited by Cartier. By 1608, when Samuel de Champlain visited the area, that part of the St. Lawrence River valley had no settlements, but was controlled by the Mohawk as a hunting ground. The fate of the Iroquoian people that Cartier encountered remains a mystery, and all that can be stated for certain is when Champlain arrived, they were gone.[61] On the Gaspé peninsula, Champlain encountered Algonquian-speaking groups. The precise identity of any of these groups is still debated. On July 29, 1609, Champlain assisted his allies in defeating a Mohawk war party by the shores of what is now called Lake Champlain, and again in June 1610, Champlain fought against the Mohawks.[62]

The Iroquois became well known in the southern colonies in the 17th century by this time. After the first English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia (1607), numerous 17th-century accounts describe a powerful people known to the Powhatan Confederacy as the Massawomeck, and to the French as the Antouhonoron. They were said to come from the north, beyond the Susquehannock territory. Historians have often identified the Massawomeck / Antouhonoron as the Haudenosaunee.

In 1649, an Iroquois war party, consisting mostly of Senecas and Mohawks, destroyed the Huron village of Wendake. In turn, this ultimately resulted in the breakup of the Huron nation. With no northern enemy remaining, the Iroquois turned their forces on the Neutral Nations on the north shore of Lakes Erie and Ontario, the Susquehannocks, their southern neighbor. Then they destroyed other Iroquoian-language tribes, including the Erie, to the west, in 1654, over competition for the fur trade.[63][page needed] Then they destroyed the Mohicans. After their victories, they reigned supreme in an area from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean; from the St. Lawrence River to the Chesapeake Bay.

Michael O. Varhola has argued their success in conquering and subduing surrounding nations had paradoxically weakened a Native response to European growth, thereby becoming victims of their own success.

The Five Nations of the League established a trading relationship with the Dutch at Fort Orange (modern Albany, New York), trading furs for European goods, an economic relationship that profoundly changed their way of life and led to much over-hunting of beavers.[64]

Between 1665 and 1670, the Iroquois established seven villages on the northern shores of Lake Ontario in present-day Ontario, collectively known as the "Iroquois du Nord" villages. The villages were all abandoned by 1701.[65]

Over the years 1670–1710, the Five Nations achieved political dominance of much of Virginia west of the Fall Line and extending to the Ohio River valley in present-day West Virginia and Kentucky. As a result of the Beaver Wars, they pushed Siouan-speaking tribes out and reserved the territory as a hunting ground by right of conquest. They finally sold to British colonists their remaining claim to the lands south of the Ohio in 1768 at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix.

Historian Pekka Hämäläinen writes of the League, "There had never been anything like the Five Nations League in North America. No other Indigenous nation or confederacy had ever reached so far, conducted such an ambitious foreign policy, or commanded such fear and respect. The Five Nations blended diplomacy, intimidation, and violence as the circumstances dictated, creating a measured instability that only they could navigate. Their guiding principle was to avoid becoming attached to any single colony, which would restrict their options and risk exposure to external manipulation."[66]

Beaver Wars

Beginning in 1609, the League engaged in the decades-long Beaver Wars against the French, their Huron allies, and other neighboring tribes, including the Petun, Erie, and Susquehannock.[64] Trying to control access to game for the lucrative fur trade, they invaded the Algonquian peoples of the Atlantic coast (the Lenape, or Delaware), the Anishinaabe of the boreal Canadian Shield region, and not infrequently the English colonies as well. During the Beaver Wars, they were said to have defeated and assimilated the Huron (1649), Petun (1650), the Neutral Nation (1651),[67][68] Erie Tribe (1657), and Susquehannock (1680).[69] The traditional view is that these wars were a way to control the lucrative fur trade to purchase European goods on which they had become dependent.[70][71][page needed] Starna questions this view.[72]

Recent scholarship has elaborated on this view, arguing that the Beaver Wars were an escalation of the Iroquoian tradition of "Mourning Wars".[73] This view suggests that the Iroquois launched large-scale attacks against neighboring tribes to avenge or replace the many dead from battles and smallpox epidemics.

In 1628, the Mohawk defeated the Mahican to gain a monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch at Fort Orange (present-day Albany), New Netherland. The Mohawk would not allow northern native peoples to trade with the Dutch.[64] By 1640, there were almost no beavers left on their lands, reducing the Iroquois to middlemen in the fur trade between Indian peoples to the west and north, and Europeans eager for the valuable thick beaver pelts.[64] In 1645, a tentative peace was forged between the Iroquois and the Huron, Algonquin, and French.

In 1646, Jesuit missionaries at Sainte-Marie among the Hurons went as envoys to the Mohawk lands to protect the precarious peace. Mohawk attitudes toward the peace soured while the Jesuits were traveling, and their warriors attacked the party en route. The missionaries were taken to Ossernenon village, Kanienkeh (Mohawk Nation) (near present-day Auriesville, New York), where the moderate Turtle and Wolf clans recommended setting them free, but angry members of the Bear clan killed Jean de Lalande and Isaac Jogues on October 18, 1646.[74] The Catholic Church has commemorated the two French priests and Jesuit lay brother René Goupil (killed September 29, 1642)[75] as among the eight North American Martyrs.

In 1649 during the Beaver Wars, the Iroquois used recently-purchased Dutch guns to attack the Huron, allies of the French. These attacks, primarily against the Huron towns of Taenhatentaron (St. Ignace[76]) and St. Louis[77] in what is now Simcoe County, Ontario, were the final battles that effectively destroyed the Huron Confederacy.[78] The Jesuit missions in Huronia on the shores of Georgian Bay were abandoned in the face of the Iroquois attacks, with the Jesuits leading the surviving Hurons east towards the French settlements on the St. Lawrence.[74] The Jesuit Relations expressed some amazement that the Five Nations had been able to dominate the area "for five hundred leagues around, although their numbers are very small".[74] From 1651 to 1652, the Iroquois attacked the Susquehannock, to their south in present-day Pennsylvania, without sustained success.

In 1653 the Onondaga Nation extended a peace invitation to New France. An expedition of Jesuits, led by Simon Le Moyne, established Sainte Marie de Ganentaa in 1656 in their territory. They were forced to abandon the mission by 1658 as hostilities resumed, possibly because of the sudden death of 500 native people from an epidemic of smallpox, a European infectious disease to which they had no immunity.

From 1658 to 1663, the Iroquois were at war with the Susquehannock and their Lenape and Province of Maryland allies. In 1663, a large Iroquois invasion force was defeated at the Susquehannock main fort. In 1663, the Iroquois were at war with the Sokoki tribe of the upper Connecticut River. Smallpox struck again, and through the effects of disease, famine, and war, the Iroquois were under threat of extinction. In 1664, an Oneida party struck at allies of the Susquehannock on Chesapeake Bay.

In 1665, three of the Five Nations made peace with the French. The following year, the Governor-General of New France, the Marquis de Tracy, sent the Carignan regiment to confront the Mohawk and Oneida.[79] The Mohawk avoided battle, but the French burned their villages, which they referred to as "castles", and their crops.[79] In 1667, the remaining two Iroquois Nations signed a peace treaty with the French and agreed to allow missionaries to visit their villages. The French Jesuit missionaries were known as the "black-robes" to the Iroquois, who began to urge that Catholic converts should relocate to the Caughnawaga, Kanienkeh outside of Montreal.[79] This treaty lasted for 17 years.

1670–1701

Around 1670, the Iroquois drove the Siouan-speaking Mannahoac tribe out of the northern Virginia Piedmont region, and began to claim ownership of the territory. In 1672, they were defeated by a war party of Susquehannock, and the Iroquois appealed to the French Governor Frontenac for support:

It would be a shame for him to allow his children to be crushed, as they saw themselves to be ... they not having the means of going to attack their fort, which was very strong, nor even of defending themselves if the others came to attack them in their villages.[80]

Some old histories state that the Iroquois defeated the Susquehannock but this is undocumented and doubtful.[81] In 1677, the Iroquois adopted the majority of the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannock into their nation.[82]

In January 1676, the Governor of New York colony, Edmund Andros, sent a letter to the chiefs of the Iroquois asking for their help in King Philip's War, as the English colonists in New England were having much difficulty fighting the Wampanoag led by Metacom. In exchange for precious guns from the English, an Iroquois war party devastated the Wampanoag in February 1676, destroying villages and food stores while taking many prisoners.[83]

By 1677, the Iroquois formed an alliance with the English through an agreement known as the Covenant Chain. By 1680, the Iroquois Confederacy was in a strong position, having eliminated the Susquehannock and the Wampanoag, taken vast numbers of captives to augment their population, and secured an alliance with the English supplying guns and ammunition.[84] Together the allies battled to a standstill the French and their allies the Hurons, traditional foes of the Confederacy. The Iroquois colonized the northern shore of Lake Ontario and sent raiding parties westward all the way to Illinois Country. The tribes of Illinois were eventually defeated, not by the Iroquois, but by the Potawatomi.

In 1679, the Susquehannock, with Iroquois help, attacked Maryland's Piscataway and Mattawoman allies.[85] Peace was not reached until 1685. During the same period, French Jesuit missionaries were active in Iroquoia, which led to a voluntary mass relocation of many Haudenosaunee to the St. Lawrence valley at Kahnawake and Kanesatake near Montreal. It was the intention of the French to use the Catholic Haudenosaunee in the St. Lawrence valley as a buffer to keep the English-allied Haudenosaunee tribes, in what is now upstate New York, away from the center of the French fur trade in Montreal. The attempts of both the English and the French to make use of their Haudenosaunee allies were foiled, as the two groups of Haudenosaunee showed a "profound reluctance to kill one another".[86] Following the move of the Catholic Iroquois to the St. Lawrence valley, historians commonly describe the Iroquois living outside of Montreal as the Canadian Iroquois, while those remaining in their historical heartland in modern upstate New York are described as the League Iroquois.[87]

In 1684, the Governor General of New France, Joseph-Antoine Le Febvre de La Barre, decided to launch a punitive expedition against the Seneca, who were attacking French and Algonquian fur traders in the Mississippi river valley, and asked for the Catholic Haudenosaunee to contribute fighting men.[88] La Barre's expedition ended in fiasco in September 1684 when influenza broke out among the French troupes de la Marine while the Canadian Iroquois warriors refused to fight, instead only engaging in battles of insults with the Seneca warriors.[89] King Louis XIV of France was not amused when he heard of La Barre's failure, which led to his replacement with Jacques-René de Brisay, Marquis de Denonville (Governor General 1685–1689), who arrived in August with orders from the Sun King to crush the Haudenosaunee confederacy and uphold the honor of France even in the wilds of North America.[89] In the same year, the Iroquois again invaded Virginia and Illinois territory and unsuccessfully attacked French outposts in the latter. Trying to reduce warfare in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, later that year the Virginia Colony agreed in a conference at Albany to recognize the Iroquois' right to use the North-South path, known as the Great Warpath, running east of the Blue Ridge, provided they did not intrude on the English settlements east of the Fall Line.

In 1687, the Marquis de Denonville set out for Fort Frontenac (modern Kingston, Ontario) with a well-organized force. In July 1687 Denonville took with him on his expedition a mixed force of troupes de la Marine, French-Canadian militiamen, and 353 Indian warriors from the Jesuit mission settlements, including 220 Haudenosaunee.[89] They met under a flag of truce with 50 hereditary sachems from the Onondaga council fire, on the north shore of Lake Ontario in what is now southern Ontario.[89] Denonville recaptured the fort for New France and seized, chained, and shipped the 50 Iroquois chiefs to Marseilles, France, to be used as galley slaves.[89] Several of the Catholic Haudenosaunee were outraged at this treachery to a diplomatic party, which led to at least 100 of them to desert to the Seneca.[90] Denonville justified enslaving the people he encountered, saying that as a "civilized European" he did not respect the customs of "savages" and would do as he liked with them. On August 13, 1687, an advance party of French soldiers walked into a Seneca ambush and were nearly killed to a man; however the Seneca fled when the main French force came up. The remaining Catholic Haudenosaunee warriors refused to pursue the retreating Seneca.[89]

Denonville ravaged the land of the Seneca, landing a French armada at Irondequoit Bay, striking straight into the seat of Seneca power, and destroying many of its villages. Fleeing before the attack, the Seneca moved farther west, east and south down the Susquehanna River. Although great damage was done to their homeland, the Senecas' military might was not appreciably weakened. The Confederacy and the Seneca developed an alliance with the English who were settling in the east. The destruction of the Seneca land infuriated the members of the Iroquois Confederacy. On August 4, 1689, they retaliated by burning down Lachine, a small town adjacent to Montreal. Fifteen hundred Iroquois warriors had been harassing Montreal defenses for many months prior to that.

They finally exhausted and defeated Denonville and his forces. His tenure was followed by the return of Frontenac for the next nine years (1689–1698). Frontenac had arranged a new strategy to weaken the Iroquois. As an act of conciliation, he located the 13 surviving sachems of the 50 originally taken and returned with them to New France in October 1689. In 1690, Frontenac destroyed Schenectady, Kanienkeh, and in 1693 burned down three other Mohawk villages and took 300 prisoners.[91]

In 1696, Frontenac decided to take the field against the Iroquois, despite being seventy-six years of age. He decided to target the Oneida and Onondaga, instead of the Mohawk who had been the favorite enemies of the French.[91] On July 6, he left Lachine at the head of a considerable force and traveled to the capital of Onondaga, where he arrived a month later. With support from the French, the Algonquian nations drove the Iroquois out of the territories north of Lake Erie and west of present-day Cleveland, Ohio, regions which they had conquered during the Beaver Wars.[82] In the meantime, the Iroquois had abandoned their villages. As pursuit was impracticable, the French army commenced its return march on August 10. Under Frontenac's leadership, the Canadian militia became increasingly adept at guerrilla warfare, taking the war into Iroquois territory and attacking a number of English settlements. The Iroquois never threatened the French colony again.[92]

During King William's War (North American part of the War of the Grand Alliance), the Iroquois were allied with the English. In July 1701, they concluded the "Nanfan Treaty", deeding the English a large tract north of the Ohio River. The Iroquois claimed to have conquered this territory 80 years earlier. France did not recognize the treaty, as it had settlements in the territory at that time and the English had virtually none. Meanwhile, the Iroquois were negotiating peace with the French; together they signed the Great Peace of Montreal that same year.

French and Indian Wars

After the 1701 peace treaty with the French, the Iroquois remained mostly neutral. During the course of the 17th century, the Iroquois had acquired a fearsome reputation among the Europeans, and it was the policy of the Six Nations to use this reputation to play off the French against the British in order to extract the maximum amount of material rewards.[93] In 1689, the English Crown provided the Six Nations goods worth £100 in exchange for help against the French, in the year 1693 the Iroquois had received goods worth £600, and in the year 1701 the Six Nations had received goods worth £800.[94]

During Queen Anne's War (North American part of the War of the Spanish Succession), they were involved in planned attacks against the French. Pieter Schuyler, mayor of Albany, arranged for three Mohawk chiefs and a Mahican chief (known incorrectly as the Four Mohawk Kings) to travel to London in 1710 to meet with Queen Anne in an effort to seal an alliance with the British. Queen Anne was so impressed by her visitors that she commissioned their portraits by court painter John Verelst. The portraits are believed to be the earliest surviving oil portraits of Aboriginal peoples taken from life.[95]

In the early 18th century, the Tuscarora gradually migrated northwards towards Pennsylvania and New York after a bloody conflict with white settlers in North and South Carolina. Due to shared linguistic and cultural similarities, the Tuscarora gradually aligned with the Iroquois and entered the confederacy as the sixth Indian nation in 1722 after being sponsored by the Oneida.[27]

The Iroquois program toward the defeated tribes favored assimilation within the 'Covenant Chain' and Great Law of Peace, over wholesale slaughter. Both the Lenni Lenape, and the Shawnee were briefly tributary to the Six Nations, while subjected Iroquoian populations emerged in the next period as the Mingo, speaking a dialect like that of the Seneca, in the Ohio region. During the War of Spanish Succession, known to Americans as "Queen Anne's War", the Iroquois remained neutral, through leaning towards the British.[91] Anglican missionaries were active with the Iroquois and devised a system of writing for them.[91]

In 1721 and 1722, Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia concluded a new Treaty at Albany with the Iroquois, renewing the Covenant Chain and agreeing to recognize the Blue Ridge as the demarcation between the Virginia Colony and the Iroquois. But, as European settlers began to move beyond the Blue Ridge and into the Shenandoah Valley in the 1730s, the Iroquois objected. Virginia officials told them that the demarcation was to prevent the Iroquois from trespassing east of the Blue Ridge, but it did not prevent English from expanding west. Tensions increased over the next decades, and the Iroquois were on the verge of going to war with the Virginia Colony. In 1743, Governor Sir William Gooch paid them the sum of 100 pounds sterling for any settled land in the Valley that was claimed by the Iroquois. The following year at the Treaty of Lancaster, the Iroquois sold Virginia all their remaining claims in the Shenandoah Valley for 200 pounds in gold.[96]

During the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years' War), the League Iroquois sided with the British against the French and their Algonquian allies, who were traditional enemies. The Iroquois hoped that aiding the British would also bring favors after the war. Few Iroquois warriors joined the campaign. By contrast, the Canadian Iroquois supported the French.

In 1711, refugees from is now southern-western Germany known as the Palatines appealed to the Iroquois clan mothers for permission to settle on their land.[97] By spring of 1713, about 150 Palatine families had leased land from the Iroquois.[98] The Iroquois taught the Palatines how to grow "the Three Sisters" as they called their staple crops of beans, corn and squash and where to find edible nuts, roots and berries.[98] In return, the Palatines taught the Iroquois how to grow wheat and oats, and how to use iron ploughs and hoes to farm.[98] As a result of the money earned from land rented to the Palatines, the Iroquois elite gave up living in longhouses and started living in European style houses, having an income equal to a middle-class English family.[98] By the middle of the 18th century, a multi-cultural world had emerged with the Iroquois living alongside German and Scots-Irish settlers.[99] The settlements of the Palatines were intermixed with the Iroquois villages.[100] In 1738, an Irishman, Sir William Johnson, who was successful as a fur trader, settled with the Iroquois.[101] Johnson who become very rich from the fur trade and land speculation, learned the languages of the Iroquois and become the main intermediary between the British and the League.[101] In 1745, Johnson was appointed the Northern superintendent of Indian Affairs, formalizing his position.[102]

On July 9, 1755, a force of British Army regulars and the Virginia militia under General Edward Braddock advancing into the Ohio river valley was almost completely destroyed by the French and their Indian allies at the Battle of the Monongahela.[102] Johnson, who had the task of enlisting the League Iroquois on the British side, led a mixed Anglo-Iroquois force to victory at Lac du St Sacrement, known to the British as Lake George.[102] In the Battle of Lake George, a group of Catholic Mohawk (from Kahnawake) and French forces ambushed a Mohawk-led British column; the Mohawk were deeply disturbed as they had created their confederacy for peace among the peoples and had not had warfare against each other. Johnson attempted to ambush a force of 1,000 French troops and 700 Canadian Iroquois under the command of Baron Dieskau, who beat off the attack and killed the old Mohawk war chief, Peter Hendricks.[102] On September 8, 1755, Diskau attacked Johnson's camp, but was repulsed with heavy losses.[102] Though the Battle of Lake George was a British victory, the heavy losses taken by the Mohawk and Oneida at the battle caused the League to declare neutrality in the war.[102] Despite Johnson's best efforts, the League Iroquois remained neutral for next several years, and a series of French victories at Oswego, Louisbourg, Fort William Henry and Fort Carillon ensured the League Iroquois would not fight on what appeared to be the losing side.[103]

In February 1756, the French learned from a spy, Oratory, an Oneida chief, that the British were stockpiling supplies at the Oneida Carrying Place, a crucial portage between Albany and Oswego to support an offensive in the spring into what is now Ontario. As the frozen waters melted south of Lake Ontario on average two weeks before the waters did north of Lake Ontario, the British would be able to move against the French bases at Fort Frontenac and Fort Niagara before the French forces in Montreal could come to their relief, which from the French perspective necessitated a preemptive strike at the Oneida Carrying Place in the winter.[104] To carry out this strike, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, the Governor-General of New France, assigned the task to Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry, an officer of the troupes de le Marine, who required and received the assistance of the Canadian Iroquois to guide him to the Oneida Carrying Place.[105] The Canadian Iroquois joined the expedition, which left Montreal on February 29, 1756 on the understanding that they would only fight against the British, not the League Iroquois, and they would not be assaulting a fort.[106]

On March 13, 1756, an Oswegatchie Indian traveler informed the expedition that the British had built two forts at the Oneida Carrying Place, which caused the majority of the Canadian Iroquois to want to turn back, as they argued the risks of assaulting a fort would mean too many casualties, and many did in fact abandon the expedition.[107] On March 26, 1756, Léry's force of troupes de le Marine and French-Canadian militiamen, who had not eaten for two days, received much needed food when the Canadian Iroquois ambushed a British wagon train bringing supplies to Fort William and Fort Bull.[108] As far as the Canadian Iroquois were concerned, the raid was a success as they captured 9 wagons full of supplies and took 10 prisoners without losing a man, and for them, engaging in a frontal attack against the two wooden forts as Léry wanted to do was irrational.[109] The Canadian Iroquois informed Léry "if I absolutely wanted to die, I was the master of the French, but they were not going to follow me".[110] In the end, about 30 Canadian Iroquois reluctantly joined Léry's attack on Fort Bull on the morning of March 27, 1756, when the French and their Indian allies stormed the fort, finally smashing their way in through the main gate with a battering ram at noon.[111] Of the 63 people in Fort Bull, half of whom were civilians, only 3 soldiers, one carpenter and one woman survived the Battle of Fort Bull as Léry reported "I could not restrain the ardor of the soldiers and the Canadians. They killed everyone they encountered".[112] Afterwards, the French destroyed all of the British supplies and Fort Bull itself, which secured the western flank of New France. On the same day, the main force of the Canadian Iroquois ambushed a relief force from Fort William coming to the aid of Fort Bull, and did not slaughter their prisoners as the French did at Fort Bull; for the Iroquois, prisoners were very valuable as they increased the size of the tribe.[113]

The crucial difference between the European and First Nations way of war was that Europe had millions of people, which meant that British and French generals were willing to see thousands of their own men die in battle in order to secure victory as their losses could always be made good; by contrast, the Iroquois had a considerably smaller population, and could not afford heavy losses, which could cripple a community. The Iroquois custom of "Mourning wars" to take captives who would become Iroquois reflected the continual need for more people in the Iroquois communities. Iroquois warriors were brave, but would only fight to the death if necessary, usually to protect their women and children; otherwise, the crucial concern for Iroquois chiefs was always to save manpower.[114] The Canadian historian D. Peter MacLeod wrote that the Iroquois way of war was based on their hunting philosophy, where a successful hunter would bring down an animal efficiently without taking any losses to his hunting party, and in the same way, a successful war leader would inflict losses on the enemy without taking any losses in return.[115]

The Iroquois only entered the war on the British side again in late 1758 after the British took Louisbourg and Fort Frontenac.[103] At the Treaty of Fort Easton in October 1758, the Iroquois forced the Lenape and Shawnee who had been fighting for the French to declare neutrality.[103] In July 1759, the Iroquois helped Johnson take Fort Niagara.[103] In the ensuing campaign, the League Iroquois assisted General Jeffrey Amherst as he took various French forts by the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence valley as he advanced towards Montreal, which he took in September 1760.[103] The British historian Michael Johnson wrote the Iroquois had "played a major supporting role" in the final British victory in the Seven Years' War.[103] In 1763, Johnson left his old home of Fort Johnson for the lavish estate, which he called Johnson Hall, which become a center of social life in the region.[103] Johnson was close to two white families, the Butlers and the Croghans, and three Mohawk families, the Brants, the Hills, and the Peters.[103]

After the war, to protect their alliance, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding white settlement beyond the Appalachian Mountains. American colonists largely ignored the order, and the British had insufficient soldiers to enforce it.[116]

Faced with confrontations, the Iroquois agreed to adjust the line again in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768). Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District, had called the Iroquois nations together in a grand conference in western New York, which a total of 3,102 Indians attended.[32] They had long had good relations with Johnson, who had traded with them and learned their languages and customs. As Alan Taylor noted in his history, The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (2006), the Iroquois were creative and strategic thinkers. They chose to sell to the British Crown all their remaining claim to the lands between the Ohio and Tennessee rivers, which they did not occupy, hoping by doing so to draw off English pressure on their territories in the Province of New York.[32]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Iroquois

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.