A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Punjabi, Haryanvi, Hindi-Urdu | |

| Religion | |

| Islam, Hinduism[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Khokhar Khanzada, Gakhars, Jats, Rajputs |

Khokhar[2] are a tribe found in the Pothohar Plateau of Pakistani Punjab and the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana.[3][1] Khokhars originally followed Hinduism, although they now predominantly follow Islam in Pakistan following their large-scale conversion, while those living in India, continue to follow Hinduism.[1][4][3] Many Khokhars converted to Islam from Hinduism after coming under the influence of Baba Fariduddin Ganjshakar.[5][3][6] The Persian historian of the medieval period, Firishta, has called the then Khokhar people a "race of wild barbarians without religion and morality".[7]

History

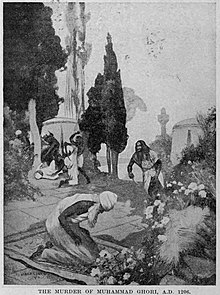

Muhammad of Ghor undertook many campaigns against the Khokhars and defeated them in his final battle fought on the bank of Jhelum and subsequently ordered a general massacre of their populace. While returning back to Ghazna, he was assassinated at Dhamiak located in the Salt Range in March 1206 by the Qarmatians whom he persecuted during his reign.[8][9] Some later acoounts attributed the assassination of Muhammad of Ghor to the Hindu Khokhars, however these later accounts are not corroborated by early Persian chroniclers who confirmed that his assassins were from the rival Ismāʿīlīyah sect of Shia Muslims.[10][11]

During his final campaign, Muhammad also took many of the Khokars as prisoners who were later forcefully converted to Islam from Hinduism.[12] During the same expedition, he also converted many other Hindu Khokhars and Buddhists who lived between Ghazna and Punjab. According to the Persian chroniclers "about three or four lakhs of infidels who wore the sacred thread were made Muslamans during this campaign".[13] The 16th century Indo-Persian historian, Ferishta states - "most of the infidels who resided between the mountains of Ghazna and Indus were converted to the true faith (Islam)".[12]

Under Delhi Sultanate

In 1240 CE, Razia, daughter of Shams-ud-din Iltutmish, and her husband, Altunia, attempted to recapture the throne from her brother, Muizuddin Bahram Shah. She is reported to have led an army composed mostly of mercenaries from the Khokhars of Punjab.[14] [15] From 1246 to 1247, Balban mounted an expedition as far as the Salt Range to eliminate the Khokhars which he saw as a threat.[16]

Although Lahore was controlled by the government in Delhi in 1251, it remained in ruins for the next twenty years, being attacked multiple times by the Mongols and their Khokhar allies.[17] Around the same time, a Mongol commander named Hulechu occupied Lahore, and forged an alliance with Khokhar chief Gul Khokhar, the erstwhile ally of Muhammad's father.[18]

In 1320, Ghazi Malik launched an attack with the use of an army of Khokhar tribesmen and killed the then Sultan of Delhi, Khusro Khan to assume power.[19][20]

The governor of Nagaur, Rajasthan under the Delhi Sultanate was Jalal Khan Khokhar. Jalal Khan Khokhar married the sister of the wife of Rana Chunda, the ruler of the emergent Marwar kingdom.[21] Rana Chunda was killed in a battle against Jalal Khokhar.[22]

According to Richard M. Eaton, Khizr Khan, the founder of the Sayyid dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate was a Khokhar chieftain.[23] He travelled to Samarkand and profited from the contacts he made with the Timurid society.[24]

Independent Chieftains

Mustafa Jasrat Khokhar (sometimes Jasrath or Dashrath)[25] was the son of Shaikha Khokhar. He became leader of the Khokhars after the death of Shaikha Khokhar. Later, he returned to Punjab. He supported Shahi Khan in the war for control of Kashmir against Ali Shah of Sayyid dynasty and was later rewarded for his victory. Later, he attempted to conquer Delhi, after the death of Khizr Khan. He succeeded only partially, while winning campaigns at Talwandi and Jullundur, he was hampered by seasonal rains in his attempt to take over Sirhind.[26]

When the Punjabi Muslim Muzaffarids declared independence of a Sultanate centered in Gujarat,[27] Nagaur came under the subah of Gujarat, and Jalal Khan acknowledged the sovereignty of the Muzaffar Shah.[28] Jalal Khan became the ruler of Nagaur.[29]

Colonial era

In reference to the British Raj's recruitment policies in the Punjab Province of colonial India, vis-à-vis the British Indian Army, Tan Tai Yong remarks:

The choice of Muslims was not merely one of physical suitability. As in the case of the Sikhs, recruiting authorities showed a clear bias in favor of the dominant landowning tribes of the region, and recruitment of Punjabi Muslims was limited to those who belonged to tribes of high social standing or reputation - the "blood proud" and once politically dominant aristocracy of the tract. Consequently, socially dominant Muslim tribes such as the Gakkhars, Janjuas and Awans, and a few Rajput tribes, concentrated in the Rawalpindi and Jhelum districts, ... accounted for more than ninety percent of Punjabi Muslim recruits.[30]

In reference to the historical residence of Khokhars at their traditional seat, the Salt Range:

The history of this region (the Salt Range) from the thirteenth century onward had been a sickening record of wars between various dominant landowning and ruling clans of Punjabi Muslims including the Janjuas, Gakhars, Thathals and Bhattis for political ascendancy.[31][32]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Singh, Kumar Suresh (2003). People of India: Jammu & Kashmir. Anthropological Survey of India. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-81-7304-118-1.

Gujars of this tract are wholly Muslims, and so are the Khokhar who have only a few Hindu families. In early stages the converted Rajputs continued with preconversion practices.

- ^ (Sadhvi.), Kanakaprabhā (1989). Amarita barasā Arāvalī meṃ. darśa Sāhitya Sagha. p. 381. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Malik, M. Mazammil Hussain (1 November 2009). "Socio-Cultural and Economic Changes among Muslims Rajputs: A Case Study of Rajouri District in J&K". Epilogue. 3 (11): 48.

Rajputs Kokhar were the domiciles of India and were originally followers of Hinduism, later on they embraced Islam and with the passage of time most of them settled near Jehlam, Pindadan Khan, Ahmed Abad and Pothar. In Rajouri District, Khokhars are residing in various villages.

- ^ Surinder Singh (30 September 2019). The Making of Medieval Panjab: Politics, Society and Culture c. 1000–c. 1500. Taylor & Francis. pp. 245–. ISBN 978-1-00-076068-2.

- ^ Rajghatta, Chidanand (28 August 2019). "View: Most Pakistanis are actually Indians". The Economic Times.

- ^ Singha, Atara (1976). Socio-cultural Impact of Islam on India. Panjab University. p. 46.

After this period, we do not hear of any Hindu Gakhars or Khokhars, for during the next two or three centuries they had all come to accept Islam.

- ^ M. A. Khan (2009). Islamic Jihad: A Legacy of Forced Conversion, Imperialism, and Slavery. iUniverse. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-1-4401-1846-3. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

The low caste Hindus of all kinds all over India--Bewaris, Marathas, Jats, Khokhars, Gonds, Bhils, Satnamis, Reddis and others--kept fighting he Muslim invaders from the beginning to the last days of Islamic domination. The Khokhar peasants (or Gukkurs)--who according to Freishtah, 'were a race of wild barbarians, without either religion or morality'--offered the strongest of resistance to Sultan Muhammad Ghauri, such as in Multan.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2007). History of Medieval India:800–1700. Orient Longman. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-250-3226-7.

He resorted to large-scale slaughter of the Khokhars and cowed them down. On his way back to Ghazni, he was killed by a Muslim fanatic belonging to a rival sect

- ^ C. E. Bosworth (1968), THE POLITICAL AND DYNASTIC HISTORY OF THE IRANIAN WORLD (A.D. 1000–1217), Cambridge University Press, p. 168, ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6,

The suppression of revolot in the Punjab occupied Mu'izz al-Din's closing months, for on the way back to Ghaza he was assasinated, allegedly by emmisaries of the Isma'ils whom he had often persecuted during his life time (602/1206)

- ^ Rānā Muḥammad Sarvar K̲h̲ān̲ (2005). The Rajputs:History, Clans, Culture, and Nobility. the University of Michigan. p. 66.

- ^

- ^ a b Wink 1991, p. 238.

- ^ Habib 1981, p. 133-134.

- ^ Syed (2004), p. 52

- ^ Bakshi (2003), p. 61

- ^ Basham & Rizvi (1987), p. 30

- ^ Chandra (2004), p. 66

- ^ Jackson (2003), p. 268

- ^ W. Haig (1958), The Cambridge History of India: Turks and Afghans, Volume 3, Cambridge University Press, pp 153-163

- ^ Mohammad Arshad (1967), An Advanced History of Muslim Rule in Indo-Pakistan, OCLC 297321674, pp 90-92

- ^ Rajvi Amar Singh (1992). Mediaeval History of Rajasthan: Western Rajasthan. the University of Michigan. p. 125.

- ^ Raghubir Sinh (1984). Rao Udaibhan Champawat ri khyat: Up to Rao Rinmal and genealogies of the Rinmalots. Indian Council of Historical Research.

- ^ Richard M. Eaton (2019). India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765. p. 117. ISBN 978-0520325128.

The career of Khizr Khan, a Punjabi chieftain belonging to the Khokar clan...

- ^ Orsini, Francesca (2015). After Timur left : culture and circulation in fifteenth-century North India. Oxford Univ. Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-19-945066-4. OCLC 913785752.

- ^ Pandey (1970), p. 223

- ^ Singh (1972), pp. 220–221

- ^ Krishna S. Dhir (2022). the Wonder that is Urdu. p. 498.

- ^ Rajasthan [district Gazetteers].: Nagaur. Printed at Government Central Press. 1962. p. 26.

- ^ Farīdī Faẓl Ullāh Luṭf Ullāh (1899). Mirati Sikandari; Or, The Mirror of Sikandar. Printed at the Education society's Press. p. XXI.

- ^ Yong (2005), p. 74

- ^ Bakshi, S. R. (1995). Advanced History of Medieval India. Anmol Publ. p. 142. ISBN 9788174880284.

- ^ Rajput Gotain

"" is not used in the content (see the help page).Bibliography

- Bakshi, S. R. (2003), Advanced History of Medieval India, 1606–1756, vol. 2, Anmol Publications, ISBN 9788174880284

- Basham, Arthur Llewellyn; Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas (1987) , The Wonder that was India, vol. 2, London: Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN 978-0-283-99458-6

- Chandra, Satish (2004), From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526), Har-Anand Publications, ISBN 9788124110645

- Habib, Mohammad (1981). Politics and Society During the Early Medieval Period: Collected Works of Professor Mohammad Habib. People's Publishing House.

- Jackson, Peter (2003), The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521543293, retrieved 18 August 2021

- Mazumder, Rajit K. (2003), The Indian army and the making of Punjab, Delhi: Permanent Black (dist. Orient Longman), ISBN 978-81-7824-059-6, retrieved 18 August 2021

- Pandey, Awadh Bihari (1970), Early medieval India (Third ed.), Central Book Depot

- Singh, Fauja (1972), History of the Punjab, vol. III, Patiala

- Singh, Nagendra Kumar (2000), International Encyclopaedia of Islamic Dynasties, Anmol Publications, ISBN 978-81-261-0403-1

- Syed, M. H. (2004), History of Delhi Sultanate, New Delhi: Anmol Publications, ISBN 978-81-261-1830-4

- Yong, Tan Tai (2005), The Garrison State: The Military, Government and Society in Colonial Punjab, 1849-1947, Sage Publications India, p. 74, ISBN 9780761933366

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.