A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Sultanate of Oman سلطنة عُمان (Arabic) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: نشيد السلام السلطاني "as-Salām as-Sultānī" "Sultanic Salutation" | |

Location of Oman (dark green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Muscat 23°35′20″N 58°24′30″E / 23.58889°N 58.40833°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[1] |

| Religion (2024) | |

| Demonym(s) | Omani |

| Government | Unitary Islamic absolute monarchy |

• Sultan | Haitham bin Tariq |

| Theyazin bin Haitham | |

| Legislature | Council of Oman |

| Council of State (Majlis al-Dawla) | |

| Consultative Assembly (Majlis al-Shura) | |

| Establishment | |

• Azd tribe migration | 130 |

• Al-Julanda | 629 |

| 751 | |

| 1154 | |

| 1507–1656 | |

| 1624 | |

| 1744 | |

| 8 January 1856 | |

• Sultanate of Oman | 9 August 1970 |

| 6 November 1996 (established); 2011 (amended); 2021 (amended)[4] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 309,500 km2 (119,500 sq mi) (70th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 4,520,471[5][6] (125th) |

• 2010 census | 2,773,479[7] |

• Density | 15/km2 (38.8/sq mi) (177th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | 30.75[9] medium |

| HDI (2022) | very high (59th) |

| Currency | Omani rial (OMR) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (GST) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +968 |

| ISO 3166 code | OM |

| Internet TLD | .om, عمان. |

Website www.oman.om | |

Oman,[b] officially the Sultanate of Oman,[c] is a country in West Asia. It is located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and overlooks the mouth of the Persian Gulf. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, while sharing maritime borders with Iran and Pakistan. The capital and largest city is Muscat. Oman has a population of nearly 4.7 million[11] and is the 124th most-populous country. The coast faces the Arabian Sea on the southeast, and the Gulf of Oman on the northeast. The Madha and Musandam exclaves are surrounded by United Arab Emirates on their land borders, with the Strait of Hormuz (which it shares with Iran) and the Gulf of Oman forming Musandam's coastal boundaries.

From the 17th century, the Omani Sultanate was an empire, vying with the Portuguese and British empires for influence in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. At its peak in the 19th century, Omani influence and control extended across the Strait of Hormuz to Iran and Pakistan, and as far south as Zanzibar.[12] In the 20th century, the sultanate came under the influence of the United Kingdom. For over 300 years, the relations built between the two empires were based on mutual benefit. The UK recognized Oman's geographical importance as a trading hub that secured British trading-lanes in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean and protected London's interests in the Indian sub-continent. Oman is an absolute monarchy led by a sultan, with power passed down through the male line. Qaboos bin Said was the Sultan from 1970 until his death on 10 January 2020.[13] Qaboos, who died childless, had named his cousin, Haitham bin Tariq, as his successor in a letter, and the ruling family confirmed him as the new Sultan of Oman.[14]

Formerly a maritime empire, Oman is the oldest continuously independent state in the Arab world.[15][16] It is a member of the United Nations, the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. It has oil reserves ranked 22nd globally.[15][17] In 2010, the United Nations Development Programme ranked Oman as the most-improved country in the world in terms of development during the preceding 40 years.[18] A portion of its economy involves tourism and trading fish, dates and other agricultural produce. The World Bank categorizes Oman as a high-income economy and as of 2023[update] Oman ranks as the 48th most peaceful country in the world according to the Global Peace Index.[19]

Etymology

The oldest written mention about Oman was found from a tomb located in the Mleiha Archeological Center in the United Arab Emirates.[20] The origin of Oman's name is thought to be several centuries older than the mention by Pliny the Elder's Omana[21] and Ptolemy's Omanon (Ὄμανον ἐμπόριον in Greek),[22] both probably the ancient Sohar.[23] The city or region is typically etymologized in Arabic from ʿāmin or ʿamūn ('settled' people, as opposed to the Bedouin).[23] Although a number of eponymous founders have been proposed (Oman bin Ibrahim al-Khalil, Oman bin Siba' bin Yaghthan bin Ibrahim, Oman bin Qahtan), others derive it from the name of a valley in Yemen at Ma'rib presumed to have been the origin of the city's founders, the Azd, a tribe migrating from Yemen.[24]

History

Prehistory and ancient history

At Aybut Al Auwal, in the Dhofar Governorate of Oman, a site was discovered in 2011 containing more than 100 surface scatters of stone tools, belonging to a regionally specific African lithic industry—the late Nubian Complex—known previously only from the northeast and Horn of Africa. Two optically stimulated luminescence age estimates place the Arabian Nubian Complex at 106,000 years old. This supports the proposition that early human populations moved from Africa into Arabia during the Late Pleistocene.[25]

In recent years surveys have uncovered Palaeolithic and Neolithic sites on the eastern coast. Main Palaeolithic sites include Saiwan-Ghunaim in the Barr al-Hikman.[26] Archaeological remains are particularly numerous for the Bronze Age Umm an-Nar and Wadi Suq periods. At the archaeological sites of Bat, Al-Janah, and Al-Ayn wheel-turned pottery, hand-made stone vessels, metals industry artifacts, and monumental architecture have been preserved.[27]

There is considerable agreement in sources that frankincense was used by traders in 1500 BCE. The Land of Frankincense, a UNESCO World Heritage site, dramatically illustrates that the incense constituted testimony to South Arabian civilizations.

During the 8th century BCE, it is believed that the Yaarub, the descendant of Qahtan, ruled the entire region of Yemen, including Oman. Wathil bin Himyar bin Abd-Shams (Saba) bin Yashjub (Yaman) bin Yarub bin Qahtan later ruled Oman.[28] It is thus believed that the Yaarubah were the first settlers in Oman from Yemen.[29]

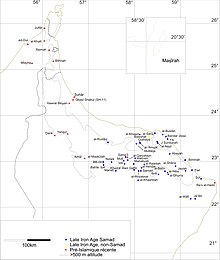

In the 1970s and 1980s, scholars like John C. Wilkinson[30] believed by virtue of oral history that in the 6th century BCE, the Achaemenids exerted control over the Omani peninsula, most likely ruling from a coastal centre such as Suhar.[31] Central Oman has its own indigenous Samad Late Iron Age cultural assemblage named eponymously from Samad al-Shan. In the northern part of the Oman Peninsula the Recent Pre-Islamic Period begins in the 3rd century BCE and extends into the 3rd century CE. Whether or not Persians brought south-eastern Arabia under their control is a moot point, since the lack of Persian archeological finds speak against this belief. Armand-Pierre Caussin de Perceval suggests that Shammir bin Wathil bin Himyar recognized the authority of Cyrus the Great over Oman in 536 BCE.[28]

Sumerian tablets referred to Oman as "Magan"[32][33] and in the Akkadian language "Makan",[34][35] a name which links Oman's ancient copper resources.[36]

Arab settlement

Over centuries tribes from western Arabia settled in Oman, making a living by fishing, farming, herding or stock breeding, and many present day Omani families trace their ancestral roots to other parts of Arabia. Arab migration to Oman started from northern-western and south-western Arabia and those who chose to settle had to compete with the indigenous population for the best arable land. When Arab tribes started to migrate to Oman, there were two distinct groups. One group, a segment of the Azd tribe migrated from Yemen in 120[37]/200 CE following the collapse of Marib Dam, while the other group migrated a few centuries before the birth of Islam from Nejd (present-day Saudi Arabia), named Nizari. Other historians believe that the Yaarubah from Qahtan which belong to an older branch, were the first settlers of Oman from Yemen, and then came the Azd.[29]

The Azd settlers in Oman are descendants of Nasr bin Azd and were later known as "the Al-Azd of Oman".[37] Seventy years after the first Azd migration, another branch of Alazdi under Malik bin Fahm, the founder of Kingdom of Tanukhites on the west of Euphrates, is believed to have settled in Oman.[37] According to Al-Kalbi, Malik bin Fahm was the first settler of Alazd.[38] He is said to have first settled in Qalhat. By this account, Malik, with an armed force of more than 6000 men and horses, fought against the Marzban, who served an ambiguously named Persian king in the battle of Salut in Oman and eventually defeated the Persian forces.[29][39][40][41] This account is, however, semi-legendary and seems to condense multiple centuries of migration and conflict as well as an amalgamation of various traditions from not only the Arab tribes but also the region's original inhabitants.[39][42][43]

In the 7th century CE, Omanis came in contact with and accepted Islam.[44][45] The conversion of Omanis to Islam is ascribed to Amr ibn al-As, who was sent by the prophet Muhammad during the Expedition of Zaid ibn Haritha (Hisma). Amer was dispatched to meet with Jaifer and Abd, the sons of Julanda who ruled Oman. They appear to have readily embraced Islam.[46]

Imamate of Oman

Omani Azd used to travel to Basra for trade, which was a centre of Islam, during the Umayyad empire. Omani Azd were granted a section of Basra, where they could settle and attend to their needs. Many of the Omani Azd who settled in Basra became wealthy merchants and, under their leader Muhallab bin Abi Sufrah, started to expand their influence of power eastwards towards Khorasan. Ibadhi Islam originated in Basra through its founder, Abdullah ibn Ibadh, around the year 650 CE; the Omani Azd in Iraq would subsequently adopt this as their predominant faith. Later, Al-hajjaj, the governor of Iraq, came into conflict with the Ibadhis, which forced them back to Oman. Among those who returned was the scholar Jaber bin Zaid. His return (and the return of many other scholars) greatly enhanced the Ibadhi movement in Oman.[47] Alhajjaj also made an attempt to subjugate Oman, then ruled by Suleiman and Said (the sons of Abbad bin Julanda). Alhajjaj dispatched Mujjaah bin Shiwah, who was confronted by Said bin Abbad. This confrontation devastated Said's army, after which he and his forces retreated to the Jebel Akhdar (mountains). Mujjaah and his forces went after Said, successfully flushing them out from hiding in Wadi Mastall. Mujjaah later moved towards the coast, where he confronted Suleiman bin Abbad. The battle was won by Suleiman's forces. Alhajjaj, however, sent another force (under Abdulrahman bin Suleiman); he eventually won the war, taking over the governance of Oman.[48][49][50]

The first elective Imamate of Oman is believed to have been established shortly after the fall of the Umayyad Dynasty in 750/755 CE, when Janaħ bin ʕibadah Alħinnawi was elected.[47][51] Other scholars claim that Janaħ bin Ibadah served as a Wāli (governor) under the Umayyad dynasty (and later ratified the Imamate), and that Julanda bin Masud was the first elected Imam of Oman, in 751 CE.[52][53] The first Imamate reached its peak power in the ninth century CE.[47] The Imamate established a maritime empire whose fleet controlled the Gulf, during the time when trade with the Abbasid Dynasty, the Far East, and Africa flourished.[54] The authority of the Imams started to decline due to power struggles, the constant interventions of Abbasid, and the rise of the Seljuk Empire.[55][52]

Nabhani dynasty

During the 11th and 12th centuries, the Omani coast was in the sphere of influence of the Seljuk Empire. They were expelled in 1154, when the Nabhani dynasty came to power.[55] The Nabhanis ruled as muluk, or kings, while the Imams were reduced to largely symbolic significance. The capital of the dynasty was Bahla.[56] The Banu Nabhan controlled the trade in frankincense on the overland route via Sohar to the Yabrin oasis, and then north to Bahrain, Baghdad and Damascus.[57] The mango-tree was introduced to Oman during the time of Nabhani dynasty, by ElFellah bin Muhsin.[29][58] The Nabhani dynasty started to deteriorate in 1507 when Portuguese colonisers captured the coastal city of Muscat, and gradually extended their control along the coast up to Sohar in the north and down to Sur in the southeast.[59] Other historians argue that the Nabhani dynasty ended earlier in 1435 CE when conflicts between the dynasty and Alhinawis arose, which led to the restoration of the elective Imamate.[29]

Portuguese era

A decade after Vasco da Gama successeded in his voyage around the Cape of Good Hope and to India in 1497–1498, the Portuguese arrived in Oman and occupied Muscat for a 143-year period, from 1507 to 1650. In need of an outpost to protect their sea lanes, the Portuguese built up and fortified the city. Remnants of Portuguese architectural style still exist. Later, several more Omani cities were colonized in the early 16th century by the Portuguese, to control the entrances of the Persian Gulf and trade in the region as part of a web of fortresses in the region, from Basra to Hormuz Island.

However, in 1552 an Ottoman fleet briefly captured the fort in Muscat, during their fight for control of the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, but soon departed after destroying the surroundings of the fortress.[60]

Later in the 17th century, using its bases in Oman, Portugal engaged in the largest naval battle ever fought in the Persian Gulf. The Portuguese force fought against a combined armada of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and English East India Company supported by the Safavid empire. The result of the battle was a draw but it resulted in the loss of Portuguese influence in the Gulf.[61]

Yaruba dynasty (1624–1744)

The Ottoman Empire temporarily captured Muscat from the Portuguese again in 1581 and held it until 1588. During the 17th century, the Omanis were reunited by the Yaruba Imams. Nasir bin Murshid became the first Yaarubah Imam in 1624, when he was elected in Rustaq.[63] Imam Nasir and his successor succeeded in the 1650s in expelling the Portuguese from their coastal domains in Oman.[47] The Omanis over time established a maritime empire that pursued the Portuguese and expelled them from all their possessions in East Africa, which were then incorporated into the Omani domains. To capture Zanzibar Saif bin Sultan, the Imam of Oman, pressed down the Swahili Coast. A major obstacle to his progress was Fort Jesus, housing the garrison of a Portuguese settlement at Mombasa. After a two-year siege, the fort fell to Imam Saif bin Sultan in 1698. Saif bin Sultan occupied Bahrain in 1700. The rivalry within the house of Yaruba over power after the death of Imam Sultan in 1718 weakened the dynasty. With the power of the Yaruba Dynasty dwindling, Imam Saif bin Sultan II eventually asked for help against his rivals from Nader Shah of Persia. A Persian force arrived in March 1737 to aid Saif. From their base at Julfar, the Persian forces eventually rebelled against the Yaruba in 1743. The Persian empire then tried to take possession of the coast of Oman until 1747.[47][64]

18th and 19th centuries

After the Omanis expelled the Persians, Ahmed bin Sa'id Albusaidi became the elected Imam of Oman in 1749, with Rustaq serving as the capital. Since the revival of the Imamate with the Yaruba dynasty, the Omanis continued with the elective system but, provided that the person is deemed qualified, gave preference to a member of the ruling family.[65] Following Imam Ahmed's death in 1783, his son, Said bin Ahmed became the elected Imam. His son, Seyyid Hamed bin Said, overthrew the representative of his father the Imam in Muscat and obtained the possession of Muscat fortress. Hamed ruled as "Seyyid". Afterwards, Seyyid Sultan bin Ahmed, the uncle of Seyyid Hamed, took over power. Seyyid Said bin Sultan succeeded Sultan bin Ahmed.[66][67] During the entire 19th century, in addition to Imam Said bin Ahmed who retained the title until he died in 1803, Azzan bin Qais was the only elected Imam of Oman. His rule started in 1868. However, the British refused to accept Imam Azzan as a ruler, as he was viewed as inimical to their interests. This view played an instrumental role in supporting the deposition of Imam Azzan in 1871 by his cousin, Sayyid Turki, a son of the late Sayyid Said bin Sultan, and brother of Sultan Barghash of Zanzibar, who Britain deemed to be more acceptable.[68]

Oman's Imam Sultan, defeated ruler of Muscat, was granted sovereignty over Gwadar, an area of modern-day Pakistan.[note 1][69]

British de facto colonisation

The British empire was keen to dominate southeast Arabia to stifle the growing power of other European states and to curb the Omani maritime power that grew during the 17th century.[70][54] The British empire over time, starting from the late 18th century, began to establish a series of treaties with the sultans with the objective of advancing British political and economic interest in Muscat, while granting the sultans military protection.[54][70] In 1798, the first treaty between the British East India Company and the Albusaidi dynasty was signed by Sayyid Sultan bin Ahmed. The treaty aimed to block commercial competition of the French and the Dutch as well as obtain a concession to build a British factory at Bandar Abbas.[71][47][72] A second treaty was signed in 1800, which stipulated that a British representative shall reside at the port of Muscat and manage all external affairs with other states.[72] As the Omani Empire weakened, the British influence over Muscat grew throughout the nineteenth century.[62]

In 1854, a deed of cession of the Omani Kuria Muria islands to Britain was signed by the sultan of Muscat and the British government.[74] The British government achieved predominating control over Muscat, which, for the most part, impeded competition from other nations.[75] Between 1862 and 1892, the Political Residents, Lewis Pelly and Edward Ross, played an instrumental role in securing British supremacy over the Persian Gulf and Muscat by a system of indirect governance.[68] By the end of the 19th century, and with the loss of its African dominions and its revenues, British influence increased to the point that the sultans became heavily dependent on British loans and signed declarations to consult the British government on all important matters.[70][76][77][78] The Sultanate thus came de facto under the British sphere.[77][79]

Zanzibar was a valuable property as the main slave market of the Swahili Coast as well as being a major producer of cloves, and became an increasingly important part of the Omani empire, a fact reflected by the decision of the Sayyid Sa'id bin Sultan, to make it the capital of the empire in 1837. In 1856, under British arbitration, Zanzibar and Muscat became two different sultanates.[80]

Treaty of Seeb

The Hajar Mountains, of which the Jebel Akhdar is a part, separate the country into two distinct regions: the interior, and the coastal area dominated by the capital, Muscat.[citation needed] The British imperial development over Muscat and Oman during the 19th century led to the renewed revival of the cause of the Imamate in the interior of Oman, which has appeared in cycles for more than 1,200 years in Oman.[54] The British Political Agent, who resided in Muscat, owed the alienation of the interior of Oman to the vast influence of the British government over Muscat, which he described as being completely self-interested and without any regard to the social and political conditions of the locals.[81] In 1913, Imam Salim Alkharusi instigated an anti-Muscat rebellion that lasted until 1920 when the Sultanate established peace with the Imamate by signing the Treaty of Seeb. The treaty was brokered by Britain, which had no economic interest in the interior of Oman during that point of time. The treaty granted autonomous rule to the Imamate in the interior of Oman and recognized the sovereignty of the coast of Oman, the Sultanate of Muscat.[70][82][83][84] In 1920, Imam Salim Alkharusi died and Muhammad Alkhalili was elected.[47]

On 10 January 1923, an agreement between the Sultanate and the British government was signed in which the Sultanate had to consult with the British political agent residing in Muscat and obtain the approval of the High Government of India to extract oil in the Sultanate.[85] On 31 July 1928, the Red Line Agreement was signed between Anglo-Persian Company (later renamed British Petroleum), Royal Dutch/Shell, Compagnie Française des Pétroles (later renamed Total), Near East Development Corporation (later renamed ExxonMobil) and Calouste Gulbenkian (an Armenian businessman) to collectively produce oil in the post-Ottoman Empire region, which included the Arabian peninsula, with each of the four major companies holding 23.75 percent of the shares while Calouste Gulbenkian held the remaining 5 percent shares. The agreement stipulated that none of the signatories was allowed to pursue the establishment of oil concessions within the agreed on area without including all other stakeholders. In 1929, the members of the agreement established Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC).[86] On 13 November 1931, Sultan Taimur bin Faisal abdicated.[87]

Reign of Sultan Said (1932–1970)

Said bin Taimur became the sultan of Muscat officially on 10 February 1932. The rule of sultan Said bin Taimur, a very complex character, was backed by the British government, and has been characterised as being feudal, reactionary and isolationist.[84][54][77][88] The British government maintained vast administrative control over the Sultanate as the defence secretary and chief of intelligence, chief adviser to the sultan and all ministers except for two were British.[77][89] In 1937, an agreement between the sultan and Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), a consortium of oil companies that was 23.75% British owned, was signed to grant oil concessions to IPC. After failing to discover oil in the Sultanate, IPC was intensely interested in some promising geological formations near Fahud, an area located within the Imamate. IPC offered financial support to the sultan to raise an armed force against any potential resistance by the Imamate.[90][91]

In a 1951 treaty covering commerce, oil reserves and navigation, the United Kingdom recognized the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman as a fully independent state.

In 1955, the exclave coastal Makran strip acceded to Pakistan and was made a district of its Balochistan province, while Gwadar remained in Oman. On 8 September 1958, Pakistan purchased the Gwadar enclave from Oman for US$3 million.[note 2][92] Gwadar then became a tehsil in the Makran district.

Jebel Akhdar War

Sultan Said bin Taimur expressed his interest in occupying the Imamate right after the death of Imam Alkhalili, thus taking advantage of any potential instability that might occur within the Imamate when elections were due, to the British government.[93] The British political agent in Muscat believed that the only method of gaining access to the oil reserves in the interior was by assisting the sultan in taking over the Imamate.[94] In 1946, the British government offered arms and ammunition, auxiliary supplies and officers to prepare the sultan to attack the interior of Oman.[95] In May 1954, Imam Alkhalili died and Ghalib Alhinai was elected Imam.[96] Relations between the Sultan Said bin Taimur, and Imam Ghalib Alhinai frayed over their dispute about oil concessions.

In December 1955, Sultan Said bin Taimur sent troops of the Muscat and Oman Field Force to occupy the main centres in Oman, including Nizwa, the capital of the Imamate of Oman, and Ibri.[82][97] The Omanis in the interior led by Imam Ghalib Alhinai, Talib Alhinai, the brother of the Imam and the Wali (governor) of Rustaq, and Suleiman bin Hamyar, who was the Wali (governor) of Jebel Akhdar, defended the Imamate in the Jebel Akhdar War against British-backed attacks by the Sultanate. In July 1957, the Sultan's forces were withdrawing, but they were repeatedly ambushed, sustaining heavy casualties.[82] Sultan Said, however, with the intervention of British infantry (two companies of the Cameronians), armoured car detachments from the British Army and RAF aircraft, was able to suppress the rebellion.[98] The Imamate's forces retreated to the inaccessible Jebel Akhdar.[98][90]

Colonel David Smiley, who had been seconded to organise the Sultan's Armed Forces, managed to isolate the mountain in autumn 1958 and found a route to the plateau from Wadi Bani Kharus.[99] On 4 August 1957, the British Foreign Secretary gave the approval to carry out air strikes without prior warning to the locals residing in the interior of Oman.[88] Between July and December 1958, the British RAF made 1,635 raids, dropping 1,094 tons and firing 900 rockets at the interior of Oman targeting insurgents, mountain top villages, water channels and crops.[77][88] On 27 January 1959, the Sultanate's forces occupied the mountain in a surprise operation.[99] Imam Ghalib, his brother Talib and Sulaiman managed to escape to Saudi Arabia, where the Imamate's cause was promoted until the 1970s.[99] The exiled partisans of the now abolished Imamate of Oman presented the case of Oman to the Arab League and the United Nations.[100][101] On 11 December 1963, the UN General Assembly decided to establish an Ad-Hoc Committee on Oman to study the 'Question of Oman' and report back to the General Assembly.[102] The UN General Assembly adopted the 'Question of Oman' resolution in 1965, 1966 and again in 1967 that called upon the British government to cease all repressive action against the locals, end British control over Oman and reaffirmed the inalienable right of the Omani people to self-determination and independence.[103][104][79][105][106][107]

Dhofar War

In the Dhofar War, which began in 1963, pro-Soviet forces were pitted against government troops. As the rebellion threatened the Sultan's control of Dhofar, Sultan Said bin Taimur was deposed in a bloodless coup in 1970 by his son Qaboos bin Said with British support. Qaboos expanded the Sultan of Oman's Armed Forces, modernized the state's administration and introduced social reforms. The uprising was finally put down in 1976 with the help of forces from Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan and Britain.

Modern history (1970–2020)

After deposing his father in 1970, Sultan Qaboos opened up the country, removed "Muscat and" from the country's name, embarked on economic reforms, and followed a policy of modernisation marked by increased spending on health, education and welfare.[108] Saudi Arabia invested in the development of the Omani education system, sending Saudi teachers on its own expense.[109][110] Slavery, once a cornerstone of the country's trade and development, was outlawed in 1970.[111]

In 1971, Oman joined the United Nations, as did Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

In 1981, Oman became a founding member of the six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council. Political reforms were eventually introduced. The country adopted its present national flag in 1995, resembling the previous flag but with a thicker stripe. In 1997, a royal decree was issued granting women the right to vote, and stand for election to the Majlis al-Shura, the Consultative Assembly of Oman. Two women were duly elected to the body. In 2002, voting rights were extended to all citizens over the age of 21, and the first elections to the Consultative Assembly under the new rules were held in 2003. In 2004, the Sultan appointed Oman's first female minister with portfolio, Sheikha Aisha bint Khalfan bin Jameel al-Sayabiyah, to the post of National Authority for Industrial Craftsmanship.[112] Despite these changes, there was little change to the actual political makeup of the government. The Sultan continued to rule by decree. Nearly 100 suspected Islamists were arrested in 2005 and 31 people were convicted of trying to overthrow the government. They were ultimately pardoned in June of the same year.[15]

Inspired by the Arab Spring uprisings that were taking place throughout the region, protests occurred in Oman during the early months of 2011. While they did not call for the ousting of the regime, demonstrators demanded political reforms, improved living conditions and the creation of more jobs. They were dispersed by riot police in February 2011. Sultan Qaboos reacted by promising jobs and benefits. In October 2011, elections were held to the Consultative Assembly, to which Sultan Qaboos promised greater powers. The following year, the government began a crackdown on internet criticism. In September 2012, trials began of 'activists' accused of posting "abusive and provocative" criticism of the government online. Six were given jail terms.[113]

Qaboos, the Arab world's longest-serving ruler, died on 10 January 2020.[114] Leaving no heir on succession, on 11 January 2020 Qaboos was succeeded by his first cousin Haitham bin Tariq.[115]

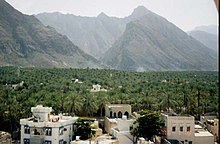

Geography

Oman lies between latitudes 16th parallel north and 28th parallel north, and longitudes 52nd meridian east and 60th meridian east. A gravel desert plain covers most of central Oman, with mountain ranges along the north (Hajar Mountains) and southeast coast (Dhofar Mountains),[116][117] where the country's main cities are located: the capital city Muscat, Sohar and Sur in the north, and Salalah in the south and Musandam. Oman's climate is hot and dry in the interior and humid along the coast.

The peninsula of Musandam (Musandem), strategically located on the Strait of Hormuz, is an exclave separated from the rest of Oman by the United Arab Emirates.[118]

Madha, another exclave, is an enclave within UAE territory located halfway between the Musandam Peninsula and the main body of Oman.[118] Madha, part of the Musandam governorate, covers approximately 75 square kilometres (29 sq mi). Madha's boundary was settled in 1969, with the north-east corner of Madha barely 10 metres (33 ft) from the Fujairah road. Within the Madha exclave is a UAE enclave called Nahwa, belonging to the Emirate of Sharjah, situated about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) west of the town of New Madha, and consisting of about forty houses with a clinic and telephone exchange.[119]

The central desert of Oman is a source of meteorites for scientific analysis.[120]

Climate

Like the rest of the Persian Gulf, Oman generally has one of the hottest climates in the world—with summer temperatures in Muscat and northern Oman averaging 30 to 40 °C (86.0 to 104.0 °F).[121] Oman receives little rainfall, with annual rainfall in Muscat averaging 100 mm (3.9 in), occurring mostly in January. In the south, the Dhofar Mountains area near Salalah has a tropical-like climate and receives seasonal rainfall from late June to late September as a result of monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean, leaving the summer air saturated with cool moisture and heavy fog.[122] Summer temperatures in Salalah range from 20 to 30 °C (68.0 to 86.0 °F)—relatively cool compared to northern Oman.[123]

The mountain areas receive more rainfall, and annual rainfall on the higher parts of the Jabal Akhdar probably exceeds 400 millimetres (16 in).[124] Low temperatures in the mountainous areas leads to snow cover once every few years.[125] Some parts of the coast, particularly near the island of Masirah, sometimes receive no rain at all within the course of a year. The climate is generally very hot, with temperatures reaching around 54 °C (129.2 °F) (peak) in the hot season, from May to September.[126]

On 26 June 2018 the city of Qurayyat set the record for highest minimum temperature in a 24-hour period, 42.6°C (108.7°F).[127]

In terms of climate action, major challenges remain to be solved, per the United Nations Sustainable Development 2019 index. The CO2 emissions from energy (tCO2/capita) and CO2 emissions embodied in fossil fuel exports (kg per capita) rates are very high, while imported CO2 emissions (tCO2/capita) and people affected by climate-related disasters (per 100,000 people) rates are low.[128]

Biodiversity

Desert shrub and desert grass, common to southern Arabia, are found in Oman, but vegetation is sparse in the interior plateau, which is largely gravel desert. The greater monsoon rainfall in Dhofar and the mountains makes the growth there more luxuriant during summer; coconut palms grow plentifully on the coastal plains of Dhofar and frankincense is produced in the hills, with abundant oleander and varieties of acacia. The Hajar Mountains are a distinct ecoregion, the highest points in eastern Arabia with wildlife including the Arabian tahr.

Indigenous mammals include the leopard, hyena, fox, wolf, hare, oryx and ibex. Birds include the vulture, eagle, stork, bustard, Arabian partridge, bee eater, falcon and sunbird. In 2001, Oman had nine endangered species of mammals, five endangered types of birds,[129] and nineteen threatened plant species. Decrees have been passed to protect endangered species, including the Arabian leopard, Arabian oryx, mountain gazelle, goitered gazelle, Arabian tahr, green sea turtle, hawksbill turtle and olive ridley turtle. However, the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary is the first site ever to be deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List, following the government's 2007 decision to reduce the site's area by 90% to clear the way for oil prospectors.[130]

Local and national entities have noted unethical treatment of animals in Oman. In particular, stray dogs (and to a lesser extent, stray cats) are often the victims of torture, abuse or neglect.[131] The only approved method of decreasing the stray dog population is shooting by police officers. The Oman government has refused to implement a spay and neuter programme or create any animal shelters in the country. Cats, while seen as more acceptable than dogs, are viewed as pests and frequently die of starvation or illness.[132][133]

In recent years, Oman has become one of the newer hot spots for whale watching, highlighting the critically endangered Arabian humpback whale, sperm whales and pygmy blue whales.[134]

Politics

Oman is a unitary state and an absolute monarchy,[135] in which all legislative, executive and judiciary power ultimately rests in the hands of the hereditary Sultan. Consequently, Freedom House has routinely rated the country "Not Free".[136]

The sultan is the head of state and directly controls the foreign affairs and defence portfolios.[137] He has absolute power and issues laws by decree.[138][139]

Legal system

Oman is an absolute monarchy, with the Sultan's word having the force of law. The judiciary branch is subordinate to the Sultan. According to Oman's constitution, Sharia law is one of the sources of legislation. Sharia court departments within the civil court system are responsible for family-law matters, such as divorce and inheritance.

While ultimate power is concentrated in the Sultan[13] and Oman does not have an official separation of powers,[13] the late Sultan Qaboos declined to grant the full title Minister of Defence, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Finance to the ministers exercising those responsibilities, preferring to keep them within the Royal Domain. The current Sultan Haitham has granted the ministers responsible of those portfolios the full titles, whilst elevating the defense portfolio to that of a deputy prime minister.[13] Since 1970 all legislation has been promulgated through royal decrees, including the 1996 Basic Law.[13] The Sultan appoints the ministers, the judges, and can grant pardons and commute sentences.[13] The Sultan's authority is inviolable and the Sultan expects total subordination to his will.[13]

The administration of justice is highly personalized, with limited due process protections, especially in political and security-related cases.[140] The Basic Statute of the State[141] is supposedly the cornerstone of the Omani legal system and it operates as a constitution for the country. The Basic Statute was issued in 1996 and thus far has only been amended twice: in 2011,[142] in response to protests; and in 2021, to create the position of Crown Prince of Oman.

Though Oman's legal code theoretically protects civil liberties and personal freedoms, both are regularly ignored by the regime.[13] Women and children face legal discrimination in many areas.[13] Women are excluded from certain state benefits, such as housing loans, and are refused equal rights under the personal status law.[13] Women also experience restrictions on their self-determination in respect to health and reproductive rights.[13]

The Omani legislature is the bicameral Council of Oman, consisting of an upper chamber, the Council of State (Majlis ad-Dawlah) and a lower chamber, the Consultative Assembly (Majlis al-Shura).[143] Political parties are banned, as are any affiliations based on religion.[139] The upper chamber has 71 members, appointed by the Sultan from among prominent Omanis; it has only advisory powers.[144] The 84 members of the Consultative Assembly are elected by universal suffrage to serve four-year terms.[144] The members are appointed for three-year terms, which may be renewed once.[143] The last elections were held on 29 October 2023, and the next is due in October 2027. Oman's national anthem, As-Salam as-Sultani is dedicated to former Sultan Qaboos.

Foreign policy

Since 1970, Oman has pursued a moderate foreign policy, and has expanded its diplomatic relations dramatically. Oman is among the very few Arab countries that have maintained friendly ties with Iran.[145][146] Yusuf bin Alawi bin Abdullah is the Sultanate's Minister Responsible for Foreign Affairs.

Oman allowed the British Royal Navy and Indian Navy access to the port facilities of Al Duqm Port & Drydock.[147]

Military

SIPRI's estimation of Oman's military and security expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 2020 was 11 percent, making it the world's highest rate in that year, higher than Saudi Arabia (8.4 percent).[148] Oman's on-average military spending as a percentage of GDP between 2016 and 2018 was around 10 percent, while the world's average during the same period was 2.2 percent.[149]

Oman's military manpower totalled 44,100 in 2006, including 25,000 men in the army, 4,200 sailors in the navy, and an air force with 4,100 personnel. The Royal Household maintained 5,000 Guards, 1,000 in Special Forces, 150 sailors in the Royal Yacht fleet, and 250 pilots and ground personnel in the Royal Flight squadrons. Oman also maintains a modestly sized paramilitary force of 4,400 men.[150]

The Royal Army of Oman had 25,000 active personnel in 2006, plus a small contingent of Royal Household troops. Despite a comparative large military spending, it has been relatively slow to modernise its forces. Oman has a relatively limited number of tanks, including 6 M60A1, 73 M60A3 and 38 Challenger 2 main battle tanks, as well as 37 aging Scorpion light tanks.[150]

The Royal Air Force of Oman has approximately 4,100 men, with 36 combat aircraft and no armed helicopters. Combat aircraft include 20 aging Jaguars, 12 Hawk Mk 203s, 4 Hawk Mk 103s and 12 PC-9 turboprop trainers with a limited combat capability. It has one squadron of 12 F-16C/D aircraft. Oman also has 4 A202-18 Bravos and 8 MFI-17B Mushshaqs.[150]

The Royal Navy of Oman had 4,200 men in 2000, and is headquartered at Seeb. It has bases at Ahwi, Ghanam Island, Mussandam and Salalah. In 2006, Oman had ten surface combat vessels. These included two 1,450-ton Qahir class corvettes, and eight ocean-going patrol boats. The Omani Navy had one 2,500-ton Nasr al Bahr class LSL (240 troops, 7 tanks) with a helicopter deck. Oman also had at least four landing craft.[150] Oman ordered three Khareef class corvettes from the VT Group for £400 million in 2007. They were built at Portsmouth.[151] In 2010 Oman spent US$4.074 billion on military expenditures, 8.5% of the gross domestic product.[152] The sultanate has a long history of association with the British military and defence industry.[153] According to SIPRI, Oman was the 23rd largest arms importer from 2012 to 2016.[154]

Human rights

Torture methods in use in Oman include mock execution, beating, hooding, solitary confinement, subjection to extremes of temperature and to constant noise, abuse and humiliation.[155][156] There have been numerous reports of torture and other inhumane forms of punishment perpetrated by Omani security forces on protesters and detainees.[157] Several prisoners detained in 2012 complained of sleep deprivation, extreme temperatures and solitary confinement.[158] Homosexuality is criminalised within Oman.[159]

The Omani government decides who can or cannot be a journalist and this permission can be withdrawn at any time.[161] Censorship and self-censorship are a constant factor.[161] Omanis have limited access to political information through the media.[162] Access to news and information can be problematic: journalists have to be content with news compiled by the official news agency on some issues.[161] Through a decree by the Sultan, the government has now extended its control over the media to blogs and other websites.[161] Omanis cannot hold a public meeting without the government's approval.[161] Omanis who want to set up a non-governmental organisation of any kind need a licence.[161] The Omani government does not permit the formation of independent civil society associations.[157] Human Rights Watch issued in 2016, that an Omani court sentenced three journalists to prison and ordered the permanent closure of their newspaper, over an article that alleged corruption in the judiciary.[163]

Omani law prohibits criticism of the Sultan and government in any form or medium.[161] Oman's police do not need search warrants to enter people's homes.[161] The law does not provide citizens with the right to change their government.[161] The Sultan retains ultimate authority on all foreign and domestic issues.[161] Government officials are not subject to financial disclosure laws.[161] Criticism of government figures and politically objectionable views have been suppressed.[161] Publication of books is limited and the government restricts their importation and distribution, as with other media products.[161]

Until 2023, Omani citizens needed government permission to marry foreigners.[158] In April 2023 the law was changed by a royal decree, allowing Omani citizens to marry foreigners without government permission.[164] According to HRW, women in Oman face discrimination.[160]

The plight of domestic workers in Oman is a taboo subject.[165][166] In 2011, the Philippines government determined that out of all the countries in the Middle East, only Oman and Israel qualify as safe for Filipino migrants.[167][166] Migrant workers remained insufficiently protected against exploitation.[168]

Administrative divisions

The Sultanate is administratively divided into eleven governorates. Governorates are, in turn, divided into 60 wilayats.[169][170]

- Ad Dakhiliyah

- Ad Dhahirah

- Al Batinah North

- Al Batinah South

- Al Buraimi

- Al Wusta

- Ash Sharqiyah North

- Ash Sharqiyah South

- Dhofar

- Muscat

- Musandam

Economyedit

Oman's Basic Statute of the State expresses in Article 11 that the "national economy is based on justice and the principles of a free economy".[171] By regional standards, Oman has a relatively diversified economy, but remains dependent on oil exports. In terms of monetary value, mineral fuels accounted for 82.2 percent of total product exports in 2018.[172] Tourism is the fastest-growing industry in Oman. Other sources of income, agriculture and industry, are small in comparison and account for less than 1% of the country's exports, but diversification is seen as a priority by the government. Agriculture, often subsistence in its character, produces dates, limes, grains and vegetables, but with less than 1% of the country under cultivation, Oman is likely to remain a net importer of food.

Oman's socio-economic structure is described as being hyper-centralized rentier welfare state.[173] The largest 10 percent of corporations in Oman are the employers of almost 80 percent of Omani nationals in the private sector. Half of the private sector jobs are classified as elementary. One third of employed Omanis are in the private sector, while the remaining majority are in the public sector.[174] A hyper-centralized structure produces a monopoly-like economy, which hinders having a healthy competitive environment between businesses.[173]

Since a slump in oil prices in 1998, Oman has made active plans to diversify its economy and is placing a greater emphasis on other areas of industry, namely tourism and infrastructure. Oman had a 2020 Vision to diversify the economy established in 1995, which targeted a decrease in oil's share to less than 10 percent of GDP by 2020, but it was rendered obsolete in 2011. Oman then established 2040 Vision.[173] A free-trade agreement with the United States took effect 1 January 2009, eliminated tariff barriers on all consumer and industrial products, and also provided strong protections for foreign businesses investing in Oman.[175] Tourism, another source of Oman's revenue, is on the rise.[176]

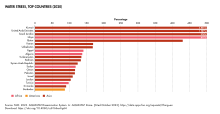

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Oman by country as of 2017[177]

Oman's foreign workers send an estimated US$10 billion annually to their home states in Asia and Africa, more than half of them earning a monthly wage of less than US$400.[178] The largest foreign community is from the Indian states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat and the Punjab,[179] representing more than half of entire workforce in Oman. Salaries for overseas workers are known to be less than for Omani nationals, though still from two to five times higher than for the equivalent job in India.[178]

In terms of foreign direct investment (FDI), total investments in 2017 exceeded US$24 billion. The highest share of FDI went to the oil and gas sector, which represented around US$13billion (54.2 percent), followed by financial intermediation, which represented US$3.66 billion (15.3 percent). FDI is dominated by the United Kingdom with an estimated value of US$11.56billion (48 percent), followed by the UAE US$2.6 billion (10.8 percent), followed by Kuwait US$1.1 billion (4.6 percent).[177]

Oman in 2018 had a budget deficit of 32 percent of total revenue and a government debt to GDP of 47.5 percent.[180][181] Oman's military spending to GDP between 2016 and 2018 averaged 10 percent, while the world's average during the same period was 2.2 percent.[182] Oman's health spending to GDP between 2015 and 2016 averaged 4.3 percent, while the world's average during the same period was 10 percent.[183] Oman's research and development spending between 2016 and 2017 averaged 0.24 percent, which is significantly lower than the world's average (2.2 percent) during the same period.[184] Oman's government spending on education to GDP in 2016 was 6.11 percent, while the world's average was 4.8 percent (2015).[185]

| Type | Spending (% of GDP)[186][187][188][189] |

|---|---|

| Military spending | 13.73

|

| Education spending | 6.11

|

| Health spending | 4.30

|

| Research & Development spending | 0.26

|