A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Operation Storm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence, Bosnian War and the Inter-Bosnian Muslim War | |||||||||

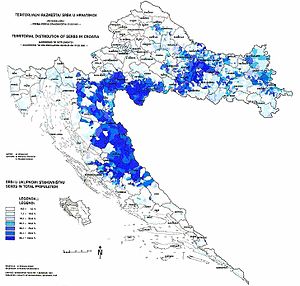

Map of Operation Storm Forces: Croatia RSK Bosnia and Herzegovina | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

174–211 killed 1,100–1,430 wounded 3 captured |

560 killed 4,000 POWs | ||||||||

|

Serb civilian deaths: 214 (Croatian claim) – 1,192 (Serb claim) Croat civilian deaths: 42 Refugees: 150,000–200,000 Serbs from the former RSK 21,000 Bosniaks from the former APWB 22,000 Bosniaks and Croats from the RS Other: 4 UN peacekeepers killed and 16 wounded | |||||||||

Operation Storm (Serbo-Croatian: Operacija Oluja / Операција Олуја) was the last major battle of the Croatian War of Independence and a major factor in the outcome of the Bosnian War. It was a decisive victory for the Croatian Army (HV), which attacked across a 630-kilometre (390 mi) front against the self-declared proto-state Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), and a strategic victory for the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). The HV was supported by the Croatian special police advancing from the Velebit Mountain, and the ARBiH located in the Bihać pocket, in the Army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina's (ARSK) rear. The battle, launched to restore Croatian control of 10,400 square kilometres (4,000 square miles) of territory, representing 18.4% of the territory it claimed, and Bosniak control of Western Bosnia, was the largest European land battle since World War II. Operation Storm commenced at dawn on 4 August 1995 and was declared complete on the evening of 7 August, despite significant mopping-up operations against pockets of resistance lasting until 14 August.

Operation Storm was a strategic victory in the Bosnian War, effectively ending the siege of Bihać and placing the HV, Croatian Defence Council (HVO) and the ARBiH in a position to change the military balance of power in Bosnia and Herzegovina through the subsequent Operation Mistral 2. The operation built on HV and HVO advances made during Operation Summer '95, when strategic positions allowing the rapid capture of the RSK capital Knin were gained, and on the continued arming and training of the HV since the beginning of the Croatian War of Independence, when the RSK was created during the Serb Log Revolution and Yugoslav People's Army intervention. The operation itself followed an unsuccessful United Nations (UN) peacekeeping mission and diplomatic efforts to settle the conflict.

The HV's and ARBiH's strategic success was a result of a series of improvements to the armies themselves, and crucial breakthroughs made in the ARSK positions that were subsequently exploited by the HV and the ARBiH. The attack was not immediately successful at all points, but seizing key positions led to the collapse of the ARSK command structure and overall defensive capability. The HV capture of Bosansko Grahovo, just before the operation, and the special police's advance to Gračac, made it nearly impossible to defend Knin. In Lika, two guard brigades quickly cut the ARSK-held area which lacked tactical depth and mobile reserve forces, and they isolated pockets of resistance, positioned a mobile force for a decisive northward thrust into the Karlovac Corps area of responsibility (AOR), and pushed ARSK towards Banovina. The defeat of the ARSK at Glina and Petrinja, after a tough defensive, defeated the ARSK Banija Corps as well since its reserve was pinned down by the ARBiH. The RSK relied on the Republika Srpska and Yugoslav militaries as its strategic reserve, but they did not intervene in the battle. The United States also played a role in the operation by directing Croatia to a military consultancy firm, Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI), that signed a Pentagon licensed contract to advise, train and provide intelligence to the Croatian army.

The HV and the special police suffered 174–211 killed or missing, while the ARSK had 560 soldiers killed. Four UN peacekeepers were also killed. The HV captured 4,000 prisoners of war. The number of Serb civilian deaths is disputed—Croatia claims that 214 were killed, while Serbian sources cite 1,192 civilians killed or missing. The Croatian population had been years prior subjected to ethnic cleansing in the areas held by ARSK by rebel Serb forces, with an estimated 170,000–250,000 expelled and hundreds killed. During and after the offensive, around 150,000–200,000 Serbs of the area formerly held by the ARSK had fled and a variety of crimes were committed against the remaining civilians there by Croatian forces.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) later tried three Croatian generals charged with war crimes and partaking in a joint criminal enterprise designed to force the Serb population out of Croatia, although all three were ultimately acquitted and the tribunal refuted charges of a criminal enterprise. The ICTY concluded that Operation Storm was not aimed at ethnic persecution, as civilians had not been deliberately targeted. The ICTY stated that Croatian Army and Special Police committed a large number of crimes against the Serb population after the artillery assault, but that the state and military leadership was not responsible for their creation and organizing and that Croatia did not have the specific intent of displacing the country's Serb minority. However, Croatia adopted discriminatory measures to make it increasingly difficult for Serbs to return. Human Rights Watch reported that the vast majority of the abuses during the operation were committed by Croatian forces and that the abuses continued on a large scale for months afterwards, which included summary executions of Serb civilians and destruction of Serb property. In 2010, Serbia sued Croatia before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), claiming that the offensive constituted a genocide. In 2015, the court ruled that the offensive was not genocidal and affirmed the ICTY's previous findings.

Background

In August 1990, an insurgency known as the Log Revolution took place in Croatia centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around the city of Knin,[4] as well as in parts of the Lika, Kordun, and Banovina regions, and settlements in eastern Croatia with significant Serb populations.[5] The areas were subsequently formed into an internationally unrecognised proto-state, the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK), and after it declared its intention to secede from Croatia and join the Republic of Serbia, the Government of the Republic of Croatia declared the RSK a rebellion.[6]

The conflict escalated by March 1991, resulting in the Croatian War of Independence.[7] In June 1991, Croatia declared its independence as Yugoslavia disintegrated.[8] A three-month moratorium on Croatia's and the RSK's declarations followed,[9] after which the decision came into effect on 8 October.[10] During this period, the RSK initiated a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Croat civilians. In 1991, 84,000 Croats fled Serbian-held territory.[11] Most non-Serbs were expelled by early 1993. Hundreds of Croats were murdered and the total number of Croats and other non-Serbs who were expelled range from 170,000 according to the ICTY[12] and up to a quarter of a million people according to Human Rights Watch.[13] By November 1993, fewer than 400 ethnic Croats remained in the United Nations-protected area known as Sector South,[14] while a further 1,500 – 2,000 remained in Sector North.[15]

Croatian forces also engaged in ethnic cleansing against Serbs in eastern and western Slavonia and parts of the Krajina region, though on a more restricted scale and Serb victims numbered less than Croat victims of Serb forces.[16] In 1991, 70,000 Serbs were displaced from Croatian territory.[11] By October 1993, the UNHCR estimated that there was a total of 247,000 Croatian and other non-Serbian displaced persons coming from areas under the control of RSK and 254,000 Serbian displaced persons and refugees from the rest of Croatia, an estimated 87,000 of whom were inhabitants of the United Nations Protected Areas (UNPA's).[17]

During this time, Serbs living in Croatian towns, especially those near the front lines, were subjected to various forms of discrimination from being fired from jobs to having bombs planted under their cars or houses.[18] The UNHCR reported that in the Serb-controlled portions of the UNPA's, human rights abuses against Croats and non-Serbs were persistent. Some of the Krajina Serb "authorities" continued to be among the most egregious perpetrators of human rights abuses against the residual non-Serb population, as well as Serbs not in agreement with nationalistic policy. Human rights violations included killings, disappearances, beatings, harassment, forced resettlement, or exile, designed to ensure Serbian dominance of the areas.[17] In 1993, the UNHCR also reported a continued series of abuse against Serbs in Croatian government-held areas which included killings, disappearances, physical abuse, illegal detention, harassment and destruction of property.[17]

As the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) increasingly supported the RSK and the Croatian Police proved unable to cope with the situation, the Croatian National Guard (ZNG) was formed in May 1991. The ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (HV) in November.[19]

The establishment of the military of Croatia was hampered by a UN arms embargo introduced in September.[20] The final months of 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the war, culminating in the Battle of the Barracks,[21] the Siege of Dubrovnik,[22] and the Battle of Vukovar.[23]

In January 1992, an agreement to implement the Vance plan designed to stop the fighting was made by representatives of Croatia, the JNA and the UN.[24]

Ending the series of unsuccessful ceasefires, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed to Croatia to supervise and maintain the agreement.[25] A stalemate developed as the conflict evolved into static trench warfare, and the JNA soon retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a new conflict was anticipated.[24] Serbia continued to support the RSK,[26] but a series of HV advances restored small areas to Croatian control as the siege of Dubrovnik ended,[27] and Operation Maslenica resulted in minor tactical gains.[28]

In response to the HV successes, the Army of the Republic of Serb Krajina (ARSK) intermittently attacked a number of Croat towns and villages with artillery and missiles.[5][29][30]

As the JNA disengaged in Croatia, its personnel prepared to set up a new Bosnian Serb army, as Bosnian Serbs declared the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992, ahead of a 29 February – 1 March 1992 referendum on the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The referendum was later cited as a pretext for the Bosnian War.[31] Bosnian Serbs set up barricades in the capital, Sarajevo, and elsewhere on 1 March, and the next day the first fatalities of the war were recorded in Sarajevo and Doboj. In the final days of March, the Bosnian Serb army started shelling Bosanski Brod,[32] and on 4 April, Sarajevo was attacked.[33] By the end of the year, the Bosnian Serb army—renamed the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) after the Republika Srpska state was proclaimed—controlled about 70% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[34] That proportion would not change significantly over the next two years.[35] Although the war originally pitted Bosnian Serbs against non-Serbs in the country, it evolved into a three-sided conflict by the end of the year, as the Croat–Bosniak War started.[36] The RSK was supported to a limited extent by the Republika Srpska, which launched occasional air raids from Banja Luka and bombarded several cities in Croatia.[37][38]

Prelude

In November 1994, the Siege of Bihać, a theatre of operations in the Bosnian War, entered a critical stage as the VRS and the ARSK came close to capturing the town of Bihać from the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH). It was a strategic area and,[39] since June 1993, Bihać had been one of six United Nations Safe Areas established in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[40]

The Clinton administration felt that its capture by Serb forces would intensify the war and lead to a humanitarian disaster greater than any other in the conflict to that point. Amongst the United States, France and the United Kingdom, division existed regarding how to protect the area.[39][41] The US called for airstrikes against the VRS, but the French and the British opposed them citing safety concerns and a desire to maintain the neutrality of French and British troops deployed as a part of the UNPROFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In turn, the US was unwilling to commit ground troops.[42]

On the other hand, the Europeans recognized that the US was free to propose military confrontation with the Serbs while relying on the European powers to block any such move,[43] since French President François Mitterrand discouraged any military intervention, greatly aiding the Serb war effort.[44] The French stance reversed after Jacques Chirac was elected president of France in May 1995,[45] pressuring the British to adopt a more aggressive approach as well.[46]

Denying Bihać to the Serbs was strategically important to Croatia,[47] and General Janko Bobetko, the Chief of the Croatian General Staff, considered the potential fall of Bihać to represent an end to Croatia's war effort.[48]

In March 1994, the Washington Agreement was signed,[48] ending the Croat–Bosniak War, and providing Croatia with US military advisors from Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI).[49][50] The US involvement reflected a new military strategy endorsed by Bill Clinton in February 1993.[51]

As the UN arms embargo was still in place, MPRI was hired ostensibly to prepare the HV for participation in the NATO Partnership for Peace programme. MPRI trained HV officers and personnel for 14 weeks from January to April 1995. It has also been speculated in several sources,[49] including an article in The New York Times by Leslie Wayne and in various Serbian media reports,[52][53] that MPRI may also have provided doctrinal advice, scenario planning and US government satellite intelligence to Croatia,[49] although MPRI,[54] American and Croatian officials denied such claims.[55][56] In November 1994, the United States unilaterally ended the arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina,[57] in effect allowing the HV to supply itself as arms shipments flowed through Croatia.[58]

The Washington Agreement also resulted in a series of meetings between Croatian and US government and military officials in Zagreb and Washington, D.C. On 29 November 1994, the Croatian representatives proposed to attack Serb-held territory from Livno in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in order to draw away part of the force besieging Bihać and to prevent the town's capture by the Serbs. As the US officials gave no response to the proposal, the Croatian General Staff ordered Operation Winter '94 the same day, to be carried out by the HV and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO)—the main military force of Herzeg-Bosnia. In addition to contributing to the defence of Bihać, the attack shifted the HV's and HVO's line of contact closer to the RSK's supply routes.[48]

In 1994, the United States, Russia, the European Union (EU) and the UN sought to replace the Vance plan, which brought in the UNPROFOR. They formulated the Z-4 Plan giving Serb-majority areas in Croatia substantial autonomy.[59]

After numerous and frequently uncoordinated changes to the proposed plan, including leaking of its draft elements to the press in October, the Z-4 Plan was presented on 30 January 1995. Neither Croatia nor the RSK liked the plan. Croatia was concerned that the RSK might accept it, but Tuđman realised that Milošević, who would ultimately make the decision for the RSK,[60] would not accept the plan for fear that it would set a precedent for a political settlement in Kosovo—allowing Croatia to accept the plan with little possibility for it to be implemented.[59] The RSK refused to receive, let alone accept, the plan.[61]

In December 1994, Croatia and the RSK made an economic agreement to restore road and rail links, water and gas supplies, and use of a part of the Adria oil pipeline. Even though some of the agreement was never implemented,[62] a section of the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway passing through RSK territory near Okučani and the pipeline were both opened. Following a deadly incident that occurred in late April 1995 on the recently opened motorway,[63] Croatia reclaimed all of the RSK's territory in western Slavonia during Operation Flash,[64] taking full control of the territory by 4 May, three days after the battle began. In response, the ARSK attacked Zagreb using M-87 Orkan missiles with cluster munitions.[65] Subsequently, Milošević sent a senior Yugoslav Army officer to command the ARSK, along with arms, field officers and thousands of Serbs born in the RSK area who had been forcibly conscripted by the ARSK.[66]

On 17 July, the ARSK and the VRS started a fresh effort to capture Bihać by expanding on gains made during Operation Spider. The move provided the HV with a chance to extend their territorial gains from Operation Winter '94 by advancing from the Livno valley. On 22 July, Tuđman and Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović signed the Split Agreement for mutual defence, permitting the large-scale deployment of the HV in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The HV and HVO responded quickly through Operation Summer '95 (Croatian: Ljeto '95), capturing Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoč on 28–29 July.[67] The attack drew some ARSK units away from Bihać,[67][68] but not as many as expected. However, it put the HV in an excellent position,[69] as it isolated Knin from the Republika Srpska, as well as Yugoslavia.[70]

In late July and early August, there were two more attempts at resurrecting the Z-4 Plan and the 1994 economic agreement. Talks proposed on 28 July were ignored by the RSK, and last-ditch talks were held in Geneva on 3 August. These quickly broke down as Croatia and the RSK rejected a compromise proposed by Thorvald Stoltenberg, a Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General, essentially calling for further negotiations at a later date. In addition, the RSK dismissed a set of Croatian demands, including to disarm, and failed to endorse the Z-4 Plan once again. The talks were used by Croatia to prepare diplomatic ground for the imminent Operation Storm,[71] whose planning was completed during the Brijuni Islands meeting between Tuđman and military commanders on 31 July.[72]

The HV initiated large-scale mobilization in late July, soon after General Zvonimir Červenko became its new Chief of General Staff on 15 July.[73] In 2005, the Croatian weekly magazine Nacional reported that the U.S. had been actively involved in the preparation, monitoring and initiation of Operation Storm, that the green light from President Clinton was passed on by the US military attache in Zagreb, and the operations were transmitted in real time to Pentagon.[74]

Order of battle

HV, ARSK

In Bosnia and Herzegovina:

HV/HVO, VRS/ARSK, ARBiH/HVO, APWB

The HV operational plan was set out in four separate parts, designated Storm-1 through 4, which were allocated to various corps based upon their individual areas of responsibility (AORs). Each plan was scheduled to take between four and five days.[73] The forces that the HV allocated to attack the RSK were organised into five army corps: Split, Gospić, Karlovac, Zagreb and Bjelovar Corps.[75] A sixth zone was assigned to the Croatian special police inside the Split Corps AOR,[76] near the boundary with the Gospić Corps.[77] The HV Split Corps, located in the far south of the theatre of operations and commanded by Lieutenant General Ante Gotovina, was assigned the Storm-4 plan, which was the primary component of Operation Storm.[76] The Split Corps issued orders for the battle using the name Kozjak-95 instead, which was not an unusual practice.[78] The 30,000-strong Split Corps was opposed by the 10,000-strong ARSK 7th North Dalmatia Corps,[76] headquartered in Knin and commanded by Major General Slobodan Kovačević.[77] The 3,100-strong special police, deployed to the Velebit Mountain on the left flank of the Split Corps, were directly subordinated to the HV General Staff commanded by the Lieutenant General Mladen Markač.[79]

The 25,000-strong HV Gospić Corps was assigned the Storm-3 component of the operation,[80] to the left of the special police zone. It was commanded by Brigadier Mirko Norac, and opposed by the ARSK 15th Lika Corps, headquartered in Korenica and commanded by Major General Stevan Ševo.[81] The Lika Corps, consisting of about 6,000 troops, was sandwiched between the HV Gospić Corps and the ARBiH in the Bihać pocket in ARSK rear, forming a wide but a very shallow area. The ARBiH 5th Corps deployed about 2,000 troops in the zone. The Gospić Corps, assigned a 150-kilometre (93 mi) section of the front, was tasked with cutting the RSK in half and linking up with the ARBiH, while the ARBiH was tasked with pinning down ARSK forces that were in contact with the Bihać pocket.[80]

The HV Karlovac Corps, commanded by Major General Miljenko Crnjac, on the left flank of the Gospić Corps, covered the area extending from Ogulin to Karlovac, including Kordun,[82] and executed the Storm-2 plan. The corps was composed of 15,000 troops and was tasked with pinning down the ARSK forces in the area to protect the flanks of the Zagreb and Gospić Corps.[83] It had a forward command post in Ogulin and was opposed by the ARSK 21st Kordun Corps headquartered at Petrova Gora,[82] consisting of 4,000 troops in the AOR (one of its brigades was facing the Zagreb Corps).[83] Initially, the 21st Kordun Corps was commanded by Colonel Veljko Bosanac, but he was replaced by Colonel Čedo Bulat during the evening of 5 August. In addition, the bulk of the ARSK Special Units Corps was present in the area, commanded by Major General Milorad Stupar.[82] ARSK Special Units Corps was 5,000-strong, largely facing the Bihać pocket at the onset of Operation Storm. The ARSK armour and artillery in the AOR outnumbered that of the HV.[83]

The HV Zagreb Corps, assigned the Storm-1 plan, initially commanded by Major General Ivan Basarac, on the left flank of the Karlovac Corps, was deployed on three main axes of attack—towards Glina, Petrinja and Hrvatska Kostajnica. It was opposed by the ARSK 39th Banija Corps, headquartered in Glina and commanded by Major General Slobodan Tarbuk.[84] The Zagreb Corps was tasked with bypassing Petrinja to neutralize ARSK artillery and missiles potentially targeting Croatian cities, making a secondary thrust from Sunja towards Hrvatska Kostajnica. Their secondary mission was compromised when a battalion of the special police and the 81st Guards Battalion planned to spearhead the advance were deployed elsewhere forcing modifications to the plan. The Zagreb Corps was composed of 30,000 troops, while the ARSK had 9,000 facing them and about 1,000 ARBiH troops in the Bihać pocket to their rear. At the start of Operation Storm, about 3,500 ARSK troops were in contact with the ARBiH.[85] HV Bjelovar Corps, on the left flank of the Zagreb Corps, covering the area along the Una River, had a forward command post in Novska. The corps was commanded by Major General Luka Džanko. Opposite the Bjelovar Corps was a part of the ARSK Banija Corps. The Bjelovar Corps was included in the attack on 2 August and were therefore not issued a separate operations plan.[86]

The ARSK divided its forces in the area in two, subordinating the North Dalmatia and Lika Corps to the ARSK General Staff, and grouping the rest into the Kordun Operational Group commanded by Lieutenant Colonel General Mile Novaković. Territorially, the division corresponded to the North and South sectors of the UN protected areas.[87]

Estimates of the total number of troops deployed by the belligerents vary considerably. Croatian forces have been estimated from under 100,000 to 150,000,[64][88] but most sources put the figure at about 130,000 troops.[89][90] ARSK troop strength in the Sectors North and South was estimated by the HV prior to Operation Storm at approximately 43,000.[91] More detailed HV estimates of the manpower by individual ARSK corps indicated 34,000 soldiers,[92] while Serb sources quote 27,000 troops.[93] The discrepancy is usually reflected in literature as an estimate of about 30,000 ARSK troops.[89] The ARBiH deployed approximately 3,000 troops against the ARSK positions near Bihać.[83] In late 1994, the Fikret Abdić-led Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia (APWB)—a sliver of land northwest of Bihać between its ally RSK and the pocket—commanded 4,000–5,000 soldiers who were deployed south of Velika Kladuša against the ARBiH force.[94]

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Split Corps | 4th Guards Brigade | In the Bosansko Grahovo area |

| 7th Guards Brigade | ||

| 81st Guards Battalion | In the Glamoč area | |

| 1st Croatian Guards Brigade | A part of the 1st Croatian Guards Corps; Held in reserve in the Bosansko Grahovo area | |

| 6th Home Guard Regiment | In the Sinj area | |

| 126th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 144th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 142nd Home Guard Regiment | In the Šibenik area | |

| 15th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 113th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 2nd Battalion of the 9th Guards Brigade | In the Zadar area | |

| 112th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 7th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 134th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 10th Artillery-Rocket Regiment of the HVO | Supporting the Split Corps | |

| 14th Artillery Battalion | ||

| 20th Artillery (Howitzer) Battalion | ||

| Elements of the artillery battalion of the 5th Guards Brigade | ||

| 11th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | ||

| Gospić Corps | 138th Home Guard Regiment | In the Saborsko area |

| 133rd Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 9th Guards Brigade | Without its 2nd Battalion, in the Gospić area | |

| 118th Home Guard Regiment | In the Gospić area | |

| 111th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 12th Artillery Battalion | Supporting the Gospić Corps | |

| 1st Guards Brigade | Directly subordinated to the HV General Staff; Temporarily assigned to the Gospić Corps from 4–6 August | |

| Karlovac Corps | 104th Infantry Brigade | In the Karlovac area |

| 110th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 137th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 14th Home Guard Regiment | In the Ogulin area | |

| 143rd Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 99th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 1 battalion of the 148th Infantry Brigade | In reserve | |

| 7th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | Supporting the Karlovac Corps | |

| 13th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | ||

| 33rd Engineer Brigade | ||

| Zagreb Corps | 17th Home Guard Regiment | In the Sunja area |

| 103rd Infantry Brigade | ||

| 151st Infantry Brigade | ||

| 2nd Guards Brigade | In the Petrinja area | |

| 57th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 12th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 20th Home Guard Regiment | In the Petrinja and Glina areas | |

| 153rd Infantry Brigade | In the Glina area | |

| 202nd Artillery-Rocket Brigade | Supporting the Zagreb Corps | |

| 67th Military Police Battalion | ||

| 252nd Independent Signals Company | ||

| 502nd Mechanized NBC Warfare Company | ||

| 1 battalion of the 33rd Engineer Brigade | ||

| 31st Engineer Battalion | ||

| 36th Engineer-Pontoon Battalion | ||

| 1st Riverine Corps | ||

| 6th Artillery Battalion | ||

| 8th Howitzer Artillery Battalion (203mm) | ||

| 1 battalion of the 16th Artillery-Rocket Brigade | ||

| 5th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Battalion | ||

| 1 battalion of the 15th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Brigade | ||

| Bjelovar Corps | 125th Home Guard Regiment | In the Jasenovac area |

| 52nd Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 34th Engineer Battalion | ||

| 24th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 18th Artillery Battalion | ||

| 121st Home Guard Regiment | In the Okučani area |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| North Dalmatia Corps | 75th Motorized Brigade | Opposite the Split Corps |

| 92nd Motorized Brigade | ||

| 1st Light Brigade | ||

| 4th Light Brigade | ||

| 2nd Infantry Brigade | ||

| 3rd Infantry Brigade | ||

| 7th Mixed Artillery Regiment | ||

| 7th Mixed Antitank Artillery Regiment | ||

| 7th Light Artillery-Rocket Regiment | ||

| Special Units Corps | 2nd Guards Brigade | |

| Lika Corps | 9th Motorized Brigade | Opposite the Gospić Corps |

| 18th Infantry Brigade | ||

| 50th Infantry Brigade | ||