A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Pauline Hanson | |

|---|---|

Hanson in 2017 | |

| Leader of Pauline Hanson's One Nation | |

| Assumed office 29 November 2014[1] | |

| Deputy | Malcolm Roberts Steve Dickson (2017–19) Brian Burston (2016–18) |

| General Secretary | Rod Miles James Ashby (2014–19) Ian Nelson (2014) |

| Preceded by | Jim Savage |

| In office 11 April 1997 – 27 January 2002[1] | |

| Deputy | Brian Burston John Fischer (2000–02) |

| National Director | David Ettridge David Oldfield (1997–2000) |

| Preceded by | Party created |

| Succeeded by | John Fischer |

| Senator for Queensland | |

| Assumed office 2 July 2016 | |

| Preceded by | Glenn Lazarus |

| Leader of Pauline Hanson's United Australia Party | |

| In office 24 May 2007 – 31 March 2010 | |

| Deputy | Brian Burston |

| Preceded by | Party created |

| Succeeded by | Party dissolved |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Oxley | |

| In office 2 March 1996 – 3 October 1998 | |

| Preceded by | Les Scott |

| Succeeded by | Bernie Ripoll |

| Councillor of the City of Ipswich for Division 7[3][4] | |

| In office 3 April 1994[2] – 22 March 1995[2][5] | |

| Preceded by | Paul Pisasale |

| Succeeded by | Denise Hanly |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Pauline Lee Seccombe 27 May 1954 Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia |

| Political party | One Nation (1997–2002; 2013–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Independent (before 1996; 1996–1997; 2010–2013) Liberal (1996) Pauline's UAP (2007–2010) |

| Residence(s) | Beaudesert, Queensland, Australia |

| Education | Buranda Girls' School,[6] Coorparoo State School[7] |

| Occupation | Small business owner – Fish and chip shop (Marsden Hanson Pty Ltd) Administrative clerk (Taylors Elliotts Ltd) |

| Profession | Politician |

| Signature | |

| Website | www |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Elections as Leader |

||

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Australia |

|---|

|

Pauline Lee Hanson (née Seccombe, formerly Zagorski; born 27 May 1954) is an Australian politician who is the founder and leader of One Nation, a right-wing populist political party. Hanson has represented Queensland in the Australian Senate since the 2016 Federal Election.

Hanson ran a fish and chip shop before entering politics in 1994 as a member of Ipswich City Council in her home state. She joined the Liberal Party of Australia in 1995 and was preselected for the Division of Oxley in Brisbane at the 1996 federal election. She was disendorsed shortly before the election after making contentious comments about Aboriginal Australians, but remained listed as a Liberal on the ballot paper. Hanson won the election and took her seat as an independent, before co-founding One Nation in 1997 and becoming its only MP. She attempted to switch to the Division of Blair at the 1998 federal election but was unsuccessful. Nevertheless, her newly formed party experienced a surge in popularity at the 1998 Queensland state election, garnering the second-highest number of votes of any party in the state.

After her defeat in 1998, Hanson unsuccessfully contested the 2001 election as the leader of One Nation but was expelled from the party in 2002. A District Court jury found Hanson guilty of electoral fraud in 2003, but her convictions were later overturned by three judges on the Queensland Court of Appeal. She spent 11 weeks in jail prior to the appeal being heard.

Following her release, Hanson ran in several state and federal elections, as the leader of Pauline Hanson's United Australia Party and as an independent before rejoining One Nation in 2013 and becoming leader again the following year. She was narrowly defeated at the 2015 Queensland state election, but was elected to the Senate at the 2016 federal election, along with three other members of the party. She was re-elected at the 2022 federal election.

Early life and career

Hanson was born Pauline Lee Seccombe on 27 May 1954 in Woolloongabba, Queensland. She was the fifth of seven children (and the youngest daughter) to John Alfred "Jack" Seccombe and Hannorah Alousius Mary "Norah" Seccombe (née Webster).[8][9] She first received schooling at Buranda Girls' School, later attending Coorparoo State School in Coorparoo until she ended her education at age 15, shortly before her first marriage and pregnancy.

Jack and Norah Seccombe owned a fish and chip shop in Ipswich, Queensland, in which Hanson and her siblings worked from a young age, preparing meals and taking orders. At an older age, she assisted her parents with more administrative work in bookkeeping and sales ledgering.[10]

Hanson worked at Woolworths before working in the office administration of Taylors Elliotts Ltd, a subsidiary of Drug Houses of Australia (now Bickford's Australia), where she handled clerical bookkeeping and secretarial work. She left Taylors Elliotts during her first pregnancy.

In 1978, Hanson (then Pauline Zagorski) met Mark Hanson, a tradesman on Queensland's Gold Coast. They married in 1980 and established a construction business specialising in roof plumbing. Hanson handled the administrative components of the company, similar to her work with Taylors Elliotts, while her husband dealt with practical labour. In 1987, the couple divorced and the company was liquidated. She moved back to Ipswich and worked as a barmaid at what was then Booval Bowls Club. Hanson then bought a fish and chip shop with a new business partner Morrie Marsden. They established the holding company Marsden Hanson Pty Ltd and began operations from their recently opened fish and chip shop in Silkstone, a suburb of Ipswich. Hanson and Marsden both shared the administrative responsibilities of the company, but Hanson took on additional practical responsibilities, including buying supplies and produce for the shop and preparing the food, which was among many things that contributed to her notoriety during her first political campaign. Over time, Hanson acquired full control of the holding company, which was sold upon her election to Parliament in 1996.[11]

Political career

Entry into politics

Hanson's first election to office was in 1994, earning a seat on the Ipswich City Council, on the premise of an opposition to extra funding.[12] She held the seat for 11 months, before being removed in 1995 due to administrative changes.

In August 1995,[2] she joined the Liberal Party of Australia and in 1996 was endorsed as the Liberal candidate for the House of Representatives seat of Oxley, based on Ipswich, for the March 1996 Federal election. At the time, the seat was thought of as a Labor stronghold. The Labor incumbent, Les Scott, held it with an almost 15% two-party majority, making it the safest Labor seat in Queensland. Because of this, Hanson was initially dismissed and ignored by the media believing that she had no chance of winning the seat. However, Hanson received widespread media attention when, leading up to the election, she advocated the abolition of special government assistance for Aboriginal Australians, and she was disendorsed by the Liberal Party. Ballot papers had already been printed listing Hanson as the Liberal candidate, and the Australian Electoral Commission had closed nominations for the seat.[13] As a result, Hanson was still listed as the Liberal candidate when votes were cast, even though Liberal leader John Howard had declared she would not be allowed to sit with the Liberals if elected.[14] On election night, Hanson took a large lead on the first count and picked up enough Democrat preferences to defeat Scott on the sixth count. Her victory came amid Labor's near-meltdown in Queensland which saw it cut down to only two seats in the state. Hanson won 54 percent of the two-candidate preferred vote. Had she still been running as a Liberal, the 19.3-point swing would have been the largest two-party swing of the election.[15][unreliable source?] Since Hanson had been disendorsed, she entered parliament as an independent.[16]

Maiden speech

On 10 September 1996, Hanson gave her maiden speech to the House of Representatives, which was widely reported in the media. In her opening lines, Hanson said: "I won the seat of Oxley largely on an issue that has resulted in me being called a racist. That issue related to my comment that Aboriginals received more benefits than non-Aboriginals". Hanson then asserted that Australia was in danger of being "swamped by Asians", and that these immigrants "have their own culture and religion, form ghettos and do not assimilate". Hanson argued that "mainstream Australians" were instead subject to "a type of reverse racism ... by those who promote political correctness and those who control the various taxpayer funded 'industries' that flourish in our society servicing Aboriginals, multiculturalists and a host of other minority groups". This theme continued with the assertion that "present governments are encouraging separatism in Australia by providing opportunities, land, moneys and facilities available only to Aboriginals".

Among a series of criticisms of Aboriginal land rights, access to welfare and reconciliation, Hanson criticised the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), saying: "Anyone with a criminal record can, and does, hold a position with ATSIC". There then followed a short series of statements on family breakdown, youth unemployment, international debt, the Family Law Act, child support, and the privatisation of Qantas and other national enterprises. The speech also included an attack on immigration and multiculturalism, a call for the return of high-tariff protectionism, and criticism of economic rationalism.[17] Her speech was delivered uninterrupted by her fellow parliamentarians as it was the courtesy given to MPs delivering their maiden speeches.

Establishment of One Nation

In February 1997, Hanson, David Oldfield and David Ettridge founded the Pauline Hanson's One Nation political party.[18] Disenchanted rural voters attended her meetings in regional centres across Australia as she consolidated a support base for the new party. An opinion poll in May of that year indicated that the party was attracting the support of 9 per cent of Australian voters and that its popularity was primarily at the expense of the Liberal Party-National Party Coalition's base.[19]

Hanson's presence in the suburb of Dandenong, Victoria, to launch her party was met with demonstrations on 7 July 1997, with 3,000–5,000 people rallying outside. A silent vigil and multicultural concert was organised by the Greater Dandenong City Council in response to Hanson's presence, while a demonstration was organised by an anti-racism body. The majority of attendees were of Asian origin, where an open platform attracted leaders of the Vietnamese, Chinese, East Timorese and Sri Lankan communities. Representatives from churches, local community groups, lesbian and gay and socialist organisations also attended and addressed the crowd.[20]

In its late 1990s incarnation, One Nation called for zero net immigration, an end to multiculturalism and a revival of Australia's Anglo-Celtic cultural tradition which it says has been diminished, the abolition of native title and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), an end to special Aboriginal funding programs, opposition to Aboriginal reconciliation which the party says will create two nations, and a review of the 1967 constitutional referendum which gave the Commonwealth power to legislate for Aborigines. The party's economic position was to support protectionism and trade retaliation, increased restrictions on foreign capital and the flow of capital overseas, and a general reversal of globalisation's influence on the Australian economy. Domestically, One Nation opposed privatisation, competition policy, and the GST, while proposing a government subsidised people's bank to provide 2 per cent loans to farmers, small business, and manufacturers. On foreign policy, One Nation called for a review of Australia's United Nations membership, a repudiation of Australia's UN treaties, an end to foreign aid and to ban foreigners from owning Australian land.[21]

1998 re-election campaign

In 1999, The Australian reported that support for One Nation had fallen from 22% to 5%.[22] One Nation Senate candidate Lenny Spencer blamed the press together with party director David Oldfield for the October 1998 election defeat,[23] while the media reported the redirecting of preferences away from One Nation as the primary reason, with a lack of party unity, poor policy choices and an "inability to work with the media" also responsible.[24]

Ahead of the 1998 federal election, an electoral redistribution essentially split Oxley in half. Oxley was reconfigured as a marginal Labor seat, losing most of its more rural and exurban area while picking up the heavily pro-Labor suburb of Inala. A new seat of Blair was created in the rural area surrounding Ipswich.[25] Hanson knew her chances of holding the reconfigured Oxley were slim, especially after former Labor state premier Wayne Goss won preselection for the seat.[26] After considering whether to contest a Senate seat—which, by most accounts, she would have been heavily tipped to win—she opted to contest Blair.[25] Despite its very large notional Liberal majority (18.7 percent), most of her base was now located there.

Hanson launched her 1998 election campaign with a focus on jobs, rather than a focus on race/ethnicity or on "the people" against "the elites". Instead Hanson focused on unemployment and the need to create more jobs not through government schemes but by "cheap loans to business, by more apprenticeships, and by doing something about tariffs".[27]

Hanson won 36 percent of the primary vote,[28] slightly over 10% more than the second-place Labor candidate, Virginia Clarke. However, with all three major parties preferencing each other ahead of Hanson, Liberal candidate Cameron Thompson was able to win the seat despite finishing in third place on the first count. Thompson overtook Clarke on National preferences and defeated Hanson on Labor preferences.[28] It has been suggested by Thompson that Hanson's litigation against parodist Pauline Pantsdown was a distraction from the election which contributed to her loss.[29]

Nationally, One Nation gained 8.99 percent of the Senate vote[30] and 8.4% of the Representatives vote,[28] but only one MP was elected – Len Harris as a Senator for Queensland. Heather Hill had been elected to this position, but the High Court of Australia ruled that, although she was an Australian citizen, she was ineligible for election to sit as a Senator because she had not renounced her British citizenship.[31] The High Court found that, at least since 1986, Britain had counted as a 'foreign power' within the meaning of section 44(i) of the Constitution.[32] Hanson alleged in her 2007 autobiography Pauline Hanson: Untamed & Unashamed that a number of other politicians had dual citizenship yet this did not prevent them from holding positions in Parliament.

In 1998, Tony Abbott had established a trust fund called "Australians for Honest Politics Trust" to help bankroll civil court cases against the One Nation Party and Hanson herself.[33] John Howard denied any knowledge of the existence of such a fund.[34] Abbott was also accused of offering funds to One Nation dissident Terry Sharples to support his court battle against the party. However, Howard defended the honesty of Abbott in this matter.[35] Abbott conceded that the political threat One Nation posed to the Howard Government was "a very big factor" in his decision to pursue the legal attack, but he also said he was acting "in Australia's national interest". Howard also defended Abbott's actions saying "It's the job of the Liberal Party to politically attack other parties – there's nothing wrong with that."[36]

Time in office

Hanson gained extensive media coverage during her campaign and once she took her seat in the House. Her first speech attracted considerable attention for the views it expressed on Aboriginal benefits, welfare, immigration and multiculturalism. During her term in Parliament, Hanson spoke on social and economic issues such as the need for a fairer child support scheme and concern for the emergence of the working class poor. She also called for more accountable and effective administration of Indigenous affairs. Hanson's supporters viewed her as an ordinary person who challenged 'political correctness' as a threat to Australia's identity.

The reaction of the mainstream political parties was negative, with parliament passing a resolution (supported by all members except Graeme Campbell) condemning her views on immigration and multiculturalism. However, the Prime Minister at the time, John Howard, refused to censure Hanson or speak critically about her, acknowledging that her views were shared by many Australians,[37] commenting that he saw the expression of such views as evidence that the "pall of political correctness" had been lifted in Australia, and that Australians could now "speak a little more freely and a little more openly about what they feel".[38]

Hanson immediately labelled Howard a "strong leader" and said Australians were now free to discuss issues without "fear of being branded as a bigot or racist". Over the next few months, Hanson attracted populist anti-immigration sentiment and the attention of the Citizens' Electoral Council, the Australian League of Rights and other right-wing groups. Then-Immigration Minister Phillip Ruddock announced a tougher government line on refugee applications, and cut the family reunion intake by 10,000, despite an election promise to maintain immigration levels.[38] Various academic experts, business leaders and several state premiers attacked the justification offered by Ruddock, who had claimed that the reduction had been forced by continuing high unemployment. Various ethnic communities complained that this attack on multiculturalism was a cynical response to polls showing Hanson's rising popularity. Hanson herself claimed credit for forcing the government's hand.[19]

2001 election campaign

At the next federal election on 10 November 2001, Hanson ran for a Queensland senate seat but narrowly failed. She accounted for her declining popularity by claiming that the Liberals under John Howard had stolen her policies.[39]

"It has been widely recognised by all, including the media, that John Howard sailed home on One Nation policies. In short, if we were not around, John Howard would not have made the decisions he did."[39]

Other interrelated factors that contributed to her political decline from 1998 to 2002 include her connection with a series of advisors with whom she ultimately fell out (John Pasquarelli, David Ettridge and David Oldfield); disputes amongst her supporters; and a lawsuit over the organisational structure of One Nation.

In 2003, following her release from prison, Hanson unsuccessfully contested the New South Wales state election, running for a seat in the upper house. In January 2004, Hanson announced that she did not intend to return to politics.[40] but then stood as an independent candidate for one of Queensland's seats in the Senate in the 2004 federal election. At the time, Hanson declared, "I don't want all the hangers on. I don't want the advisers and everyone else. I want it to be this time Pauline Hanson." She was unsuccessful, receiving only 31.77% of the required quota of primary votes,[41] and did not pick up enough additional support through preferences. However, she attracted more votes than the One Nation party (4.54% compared to 3.14%)[41] and, unlike her former party, recovered her deposit from the Australian Electoral Commission and secured $150,000 of public electoral funding.[42] Hanson claimed to have been vilified over campaign funding.[43]

Hanson contested the electoral district of Beaudesert as an independent at the 2009 Queensland state election.[44] After an election campaign dominated by discussion over hoax photographs, she was placed third behind the Liberal National Party's Aidan McLindon and Labor's Brett McCreadie. There were conflicting media reports as to whether she had said she would not consider running again.[45][46]

On 23 July 2010, while at an event promoting her new career as a motivational speaker, Hanson expressed interest in returning to the political stage as a Liberal candidate if an invitation were to be offered by the leader Tony Abbott in the 2010 federal election.[47] No such offer was made.

Rattnergate scandal

In March 2011, Hanson ran as an independent candidate for the New South Wales Legislative Council in the 2011 state election,[48] but was not elected, receiving 2.41 percent of the primary statewide vote but losing on preferences.[49][50][51] Following the election, Hanson alleged that "dodgy staff" employed by the NSW Electoral Commission put 1,200 votes for her in a pile of blank ballots, and she claimed that she had a forwarded NSW Electoral Commission internal email as evidence of this.[52] Hanson then commenced legal proceedings to challenge the outcome of the election in the NSW Supreme Court, which sat as the Court of Disputed Returns.[53]

From the start of proceedings, the NSW Electoral Commissioner maintained the view that Hanson's claims lacked substance.[54] The man who alerted Hanson to the alleged emails, who identified himself as "Michael Rattner", failed to appear in court on 8 June 2011[55] "Rattner" was revealed to be Shaun Castle, a history teacher who posed as a journalist to obtain embargoed progressive poll results.[56]

"Michael Rattner" was a pun on Mickey Mouse and reports linked the pseudonym to an "anti-voter-fraud" organisation led by Amy McGrath and Alasdair Webster.[57]

After having refused to answer questions on the grounds of self-incrimination, Castle apologised to the court and was granted protection from prosecution by Justice McClellan, before being compelled to answer questions relating to the fraudulent email.[58] The judge ordered that Hanson's legal costs of more than $150,000 be paid by the State of New South Wales – a move which outraged Greens MP Jeremy Buckingham, who would have been replaced by Hanson had her challenge been successful. Questioning whether Hanson's legal action should have gone ahead at all given the nature of the evidence, Buckingham said that "This lack of judgement shows that she's unfit for public office."[59] Earlier, the judge, Justice McClellan, said Hanson had no other remedy but to take legal action after receiving the fraudulent email.[60]

Ousted from One Nation, forming a new party

At the 1999 election, One Nation politician David Oldfield was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Council, the state parliament's upper house. However, in 2000, Oldfield was expelled from One Nation for an alleged verbal dispute with Hanson. Within weeks, Oldfield had established the splinter group, One Nation NSW.

One Nation won three seats in the Western Australian Legislative Council at the 2001 state election, but the electoral success of One Nation began to deteriorate after this point because the split-away of One Nation NSW began to spark further lack of party unity, and a series of gaffes by One Nation members and candidates, particularly in Queensland.

Hanson resigned from One Nation in January 2002 and John Fischer, the State Leader from Western Australia, was elected the Federal President of One Nation.[61]

On 24 May 2007, Hanson launched Pauline's United Australia Party.[62] Under that banner, Hanson again contested one of Queensland's seats in the Senate in the 2007 federal election, when she received over 4 percent of total votes.[63] The party name invokes that of the historic United Australia Party.[64] Speaking on her return to politics, she stated: "I have had all the major political parties attack me, been kicked out of my own party and ended up in prison, but I don't give up."[65] In October 2007, Hanson launched her campaign song, entitled "Australian Way of Life", which included the line: "Welcome everyone, no matter where you come from."[66]

After an unsuccessful campaign in the 2009 Queensland state election, Hanson announced in 2010 that she planned to deregister Pauline's United Australia Party, sell her Queensland house and move to the United Kingdom.[67][68][69][70] The announcement was warmly welcomed by Nick Griffin, leader of the far-right British National Party (BNP).[71] When considering moving, Hanson said that she would not sell her house to Muslims.[72] However, following an extended holiday in Europe, Hanson said in November 2010 that she had decided not to move to Britain because it was "overrun with immigrants and refugees."[73] Hanson lives in Beaudesert, Queensland.[74]

Return as One Nation leader (2013–present)

In 2013, Hanson announced that she would stand in the 2013 federal election.[75] She rejoined the One Nation party and was a Senate candidate in New South Wales.[76] She did not win a seat, attracting 1.22% of the first preference vote.[77]

In November 2014, Hanson announced that she had returned as One Nation leader, prior to the party's announcement, following support from One Nation party members. She announced that she would contest the seat of Lockyer in the 2015 Queensland state election.[78] One Nation held the Queensland seat of Lockyer from 1998 to 2004. In February 2015, Hanson lost the seat by a narrow margin.[79][80][81][82]

First Senate term (2016–2022)

In mid-2015, Hanson announced that she would contest the Senate for Queensland at the 2016 federal election, and also announced the endorsement of several other candidates throughout Australia. She campaigned on a tour she called "Fed Up" in 2015, and spoke at a Reclaim Australia rally.[83] Hanson won a seat in the Senate at the election,[84] and One Nation won 9% of the vote in Queensland.[85] According to the rules governing the allocation of Senate seats following a double dissolution, Hanson served a full six-year term.[86] Hanson secured a spot on the National Broadband Network parliamentary committee.[87]

After being elected to the parliament, she and other One Nation senators voted with the governing Coalition on a number of welfare cuts,[88] and usually supports the government.[89]

On 17 August 2017, Hanson received criticism after wearing a burqa, which she claims "oppresses women", into the Senate. Attorney-General George Brandis got a standing ovation from Labor and Greens senators after he gave an "emotional" speech saying to Hanson: "To ridicule that community, to drive it into a corner, to mock its religious garments is an appalling thing to do."[90][91] Following the incident, polling found that 57% of Australians supported Hanson's call to ban the burka in public places, with 44% "strongly" supporting a ban.[92] In August 2017, the party's constitution was changed, for Hanson to become party President for as long as she may wish and to choose her successor, who may also continue until resignation.[93]

On 22 March 2018, Hanson announced that One Nation would back the Turnbull government's corporate tax cuts.[94][95][96] She subsequently reversed her position, citing the failure of the government to cut immigration levels and support coal-fired power.[97]

On 15 October 2018, Hanson proposed an "It's OK to be white" motion in the Australian Senate intended to acknowledge the "deplorable rise of anti-white racism and attacks on Western civilization".[98] It was supported by most senators from the governing Liberal-National Coalition, but was defeated 31–28 by opponents who called it a racist slogan from the white supremacist movement.[99][100] The following day, the motion was "recommitted", and this time rejected unanimously by senators in attendance, with its initial supporters in the Liberal-National Coalition saying they had voted for it due to an administrative error (One Nation did not attend the recommital vote).[101]

On 18 September 2019, the Liberal government announced that Hanson would co-chair the newly announced parliamentary inquiry into family law along with Kevin Andrews.[102] She proposed a parliament motion advocating opposition to the proposed Great Reset of the World Economic Forum, on the belief that it is cover for creating a New World Order. Her proposal was defeated by 37 votes to 2.[103]

In 2019, Hanson campaigned against a ban on climbing Uluru, a sacred site for local Aboriginal people.[104] Shortly before the ban came into effect, in August Channel Nine paid for Hanson's trip to Uluru and on their A Current Affair program she was shown in a controversial episode climbing the rock.[104]

Beginning in May 2019, Hanson was a regular contributor on Channel Nine's Today show.[105] She was removed from the role in July 2020 after describing people who lived in Melbourne public housing as drug addicts who couldn't speak English.[106]

Following the 2019 federal election, One Nation obtained $2.8 million in electoral expenses from the Australian Electoral Commission. Later, the Commission required One Nation to repay $165,442 as money that had not been spent or not spent for electoral purposes. In addition, it is reported: "Hanson has personally agreed to an enforceable undertaking. And the party must in future make sure all invoices are in Hanson’s name, the party’s name or the name of a party officer. And make sure that all invoices match payment receipts, credit card or bank statements."[107]

In June 2021, following media reports that the proposed national curriculum was "preoccupied with the oppression, discrimination and struggles of Indigenous Australians", the Australian Senate approved a motion tabled by Hanson calling on the federal government to reject Critical race theory CRT, despite it not being included in the curriculum.[108]

Second Senate term (2022–present)

In July 2022, the Senate opened with the Lord's Prayer and a Acknowledgement of Country, as normal. The ceremony includes the words: " recognises the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples as the traditional custodians of the Canberra meetings, and pays respects to elders past, present and emerging." Despite having sat through the ceremony many times before, this time Hanson stormed out of the chamber, yelling "No I don't, and I never will!"[109]

Hanson later stated that her opposition was to a motion that the Aboriginal flag and Torres Strait Islander flag, which are both official flags of Australia, should be raised inside the Senate chamber alongside the Australian flag.[109]

Racism allegations

Despite Hanson's repeated denials of charges of racism,[110] her views on race, immigration and Islam have been discussed widely in Australia. In her maiden speech to Parliament in 1996, Hanson appealed to economically disadvantaged white Australians by expressing dissatisfaction with government policy on indigenous affairs.[17] Following Hanson's maiden speech her views received negative coverage across Asian news media in 1996, and Deputy Prime Minister and Trade Minister Tim Fischer criticised the race "debate" initiated by Hanson, saying it was putting Australian exports and jobs at risk.[111] Other ministers and state and territory leaders followed Fischer's lead in criticising Hanson.[38]

In 1998, the resurgence of popularity of Hanson was met with disappointment in Asian media.[112] Her resignation from politics in 2002 was met with support from academics, politicians and the press across Asia.[113] In 2004, Hanson appeared on the nationally televised ABC interview show Enough Rope where her views were challenged.[10]

In September 2022, Hanson tweeted that Greens senator Mehreen Faruqi should "piss off back to Pakistan". This came after Faruqi was slammed over an "appalling" tweet about the Queen.[114] Subsequently, Faruqi decided to launch court proceedings against Hanson for "breaching section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act".[115]

Policies

Anti-immigration and anti-multiculturalism

In her maiden speech, Hanson proposed a drastic reduction in immigration with particular reference to immigrants from Asia. Hanson criticised the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC).[116] Condemning multiculturalism, One Nation has railed against government immigration and multicultural policies.[117] After Hanson was elected to Parliament in 1996, journalist Tracey Curro asked her on 60 Minutes whether she was xenophobic. Hanson replied, "Please explain?"[118] This response became a much-parodied catchphrase within Australian culture and was included in the title of the 2016 SBS documentary film Pauline Hanson: Please Explain!.

In 2006, Hanson stated that African immigrants were bringing diseases into Australia and were of "no benefit to this country whatsoever". She also stated her opposition to Muslim immigration.[119] Ten years after her maiden speech, its effects were still being discussed within a racism framework,[120] and were included in resources funded by the Queensland Government on "Combating racism in Queensland".[121] In 2007, Hanson publicly backed Kevin Andrews, then Minister for Immigration under John Howard, in his views about African migrants and crime.[122]

Islam

In 2015, Hanson claimed that Halal certification in Australia was funding terrorism.[123] After the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting, Hanson called for a ban on Muslim immigration to Australia.[124][125] The same year, Hanson announced policies including a ban on building new mosques until a royal commission into whether Islam is a religion or a political ideology has been held, and installing CCTV cameras in all existing mosques.[126] She has called for a moratorium on accepting Muslim immigrants into Australia.[127] In her 2016 maiden speech in the Senate, she said that "We are in danger of being swamped by Muslims who bear a culture and ideology that is incompatible with our own" and should "go back to where you came from", and called for banning Muslim migration.[128] The speech prompted a walkout by Senate members of the Australian Greens.[128]

After the January 2017 Melbourne car attack, Hanson repeated her stance on banning Muslims from entering Australia. In a live interview after the attack she stated "all terrorist attacks in this country have been by Muslims", on which she was corrected by a journalist.[129] In response, the Islamic Council of Victoria asked for a public apology for Hanson's statement.[130]

On 24 March 2017, after the 2017 Westminster attack, Hanson made an announcement in a video posted to social media, holding up a piece of paper with her own proposed hash tag “#Pray4MuslimBan”. “That is how you solve the problem, put a ban on it and then let’s deal with the issues here”, she said.[131]

On 22 June 2017 Hanson, moved a motion in the Australian Senate calling on the government to respond to the Halal inquiry. The motion was passed.[132][133]

On 17 August 2017, Hanson wore a burqa onto the floor of the Australian Senate in a move to rally support for a national ban of the religious attire, citing "national security" concerns.[134] The move quickly became widely condemned by Labor, the Greens and the Liberal Party.[135] In response, the Attorney-General George Brandis, who is tasked with giving advice on national security legislation, gave an "emotional" speech calling Hanson's stunt "an appalling thing to do" and advised Hanson "to be very very careful of the offense you may do to the religious sensibilities of other Australians", to which both Labor and Greens' Senators gave a standing ovation.[136][134]

Public opinion

After her election in 1996, an estimated 10,000 people marched in protest against racism in Melbourne, and other protests followed, while Anglican and Catholic church leaders warned that the controversy threatened the stability of Australia's multicultural society. Also repudiating Hanson's views on immigration and multiculturalism were Victorian Premier Jeff Kennett, the Queensland National Senator Ron Boswell, Sir Ronald Wilson and former Prime Minister Paul Keating.[137] At the 1997 annual conference of the Australian and New Zealand Communications Association (ANZCA) at La Trobe University, a paper was presented with the title "Phenomena and Epiphenomena: is Pauline Hanson racist?".[138] In 1998, social commentator Keith Suter argued that Hanson's views were better understood as an angry response to globalisation.[139] A poll in The Bulletin magazine at this time suggested that if Hanson formed a political party, it would win 18 percent of the vote. After months of silence, then-Prime Minister John Howard and Opposition Leader Kim Beazley proposed a bipartisan motion against racial discrimination and reaffirming support for a nondiscriminatory immigration policy. The motion was carried on the voices.[38]

Hanson did not relent in articulating her views and continued to address public meetings around Australia. The League of Rights offered financial and organisational support for her campaign against Asian immigration, and in December she announced she was considering forming a political party to contest the next election.[38] Alexander Downer, Minister for Foreign Affairs under John Howard, issued a media release calling on Hanson, David Oldfield and David Ettridge to distance themselves from racist slurs.[140] In 2000, the University of NSW Press published the book Race, Colour and Identity in Australia and New Zealand,[141] which identified Hanson as a central figure in the "racism debate" in Australia of the 1990s, noting that senior Australian academics such as Jon Stratton, Ghassan Hage and Andrew Jakubowicz had explored Hanson's significance in an international as well as national context.[142]

Academics, commentators and political analysts have continued to discuss Hanson's legacy and impact upon Australian politics since her rise to prominence in the 1990s and her political comeback in 2016. Milton Osborne noted that public opinion research indicated Hanson's initial support in the 1990s was not necessarily motivated by racist or anti-immigration sentiments, but instead from voters concerned about globalisation and unemployment.[143] In 2019, Hans-Georg Betz identified Hanson as among the first populist politicians to mobilize a public following by targeting "the intellectual elite" in their messages, and that in the twentyfirst century, with "today’s army of self-styled commentators and pundits summarily dismissing radical right-wing populist voters as uncouth, uneducated plebeians intellectually incapable of understanding the blessings of progressive identity politics, Hanson’s anti-elite rhetoric anno 1996 proved remarkably prescient, if rather tame".[144][145]

Personal life

Hanson lives in Beaudesert, Queensland, on a large property.[146] She purchased an investment property in Maitland, New South Wales in 2012, selling it in 2023.[147]

During her first term in political office, Hanson and her younger children were guarded by security for extended amounts of time daily. Hanson was under escort almost completely, and while her younger children were largely kept out of public exposure, they were escorted to-and-from school and on other activities. The mail received at Hanson's office was moved to another location and checked before it was re-distributed back to the office.[citation needed]

In 2006, Hanson acquired a real estate licence.[citation needed]

Relationships and children

In 1971, Hanson (then Pauline Seccombe) married Walter Zagorski, a former field representative and mining industry labourer from Poland, who had escaped war-torn Europe with his mother and arrived in Australia as refugees. He met Hanson when they both worked for the Drug Houses of Australia subsidiary Taylors Elliots Ltd. They had two children. In 1975, Hanson left Zagorski after discovering that he had been involved in several extramarital affairs. They reconciled briefly in 1977, but divorced later that year when Zagorski left Hanson for another woman.[citation needed]

In 1980, Hanson (then Pauline Zagorski) married Mark Hanson, a divorced tradesman working on the Gold Coast in Queensland. They honeymooned in South-East Asia. Mark Hanson had a daughter, Amanda (born 1977), from his previous marriage, and he later had two children with Hanson: Adam (born 1981) and Lee (born 1984). Together they established a trades and construction business, in which Hanson was in charge of the administrative and bookkeeping work, and would on occasions assist her husband on more practical work. Hanson has written about her difficult marriage, where alcohol and domestic violence impacted her family. They divorced in 1987.[148]

In 1988, Hanson began a relationship with Morrie Marsden, a businessman in Queensland. Together, they established a catering service under the holding company Marsden Hanson Pty Ltd, and operated from their fish and chips store, Marsden's Seafood, in Silkstone, Queensland. Marsden worked on Hanson's campaign for political office in the seat of Oxley in 1996, and was a member of her staff after her election. When Hanson began to receive national and international media attention for her views, Marsden left the relationship. Hanson had begun a relationship with Ipswich man Rick Gluyas in 1994. Gluyas encouraged her to run as a candidate in the 1994 Ipswich City Council election, in which he also ran. Both were elected. Hanson and Gluyas ended their relationship some time after this, with Hanson retaining the home and property they had owned jointly at Coleyville, near Ipswich.[149][150]

In 1996, Hanson began a relationship with David Oldfield. In 2000, all of Hanson's relations with Oldfield ended when he was dismissed from Pauline Hanson's One Nation.[151]

In 2005, Hanson began a relationship with Chris Callaghan, a country music singer and political activist. He wrote and composed the song "The Australian Way of Life", which was used in Hanson's 2007 campaign for the Australian Senate, under her new United Australia Party. In 2007, Hanson revealed that she and Callaghan were engaged. However, in 2008, Hanson broke off the relationship.[151]

In 2011, while campaigning for the New South Wales Legislative Council, Hanson began a relationship with property developer and real estate agent Tony Nyquist.[152][153]

Fraud conviction and reversal

A 1999 civil suit reached the Queensland Court of Appeal in 2000 involving disgruntled former One Nation member Terry Sharples and led to a finding of fraud when registering One Nation as a political party,[154] Hanson faced bankruptcy and made an appeal to supporters for donations.

On 20 August 2003, a jury in the District Court of Queensland convicted Hanson and David Ettridge of electoral fraud. Both Hanson and Ettridge were wrongly sentenced to three years imprisonment for falsely claiming that 500 members of the Pauline Hanson Support Movement were members of the political organisation Pauline Hanson's One Nation to register that organisation in Queensland as a political party and apply for electoral funding. Because the registration was found to be unlawful, Hanson's receipt of electoral funding worth $498,637 resulted in two further convictions for dishonestly obtaining property, each with three-year sentences, to run concurrently with the first. The sentence was widely criticised in the media and by some politicians as being too harsh.[155]

The prime minister, John Howard, said that it was "a very long, unconditional sentence" and Bronwyn Bishop said that Hanson was a political prisoner, comparing her conviction with Robert Mugabe's treatment of Zimbabwean opponents.[156] The sentence was widely criticised in the media as being too harsh.[155]

On 6 November 2003, delivering judgment the day after hearing the appeal, the Queensland Court of Appeal quashed all of Hanson and Ettridge's convictions. Hanson, having spent 11 weeks in jail, was immediately released along with Ettridge.[157] The court's unanimous decision was that the evidence did not support a conclusion beyond reasonable doubt that the people on the list were not members of the Pauline Hanson's One Nation party and that Hanson and Ettridge knew this when the application to register the party was submitted. Accordingly, the convictions regarding registration were quashed. The convictions regarding funding, which depended on the same facts, were also quashed.[156] This decision did not specifically follow the Sharples case, where the trial judge's finding of such fraud had not been overturned in the appeal by Hanson and Ettridge. That case was distinguished as a civil suit – in administrative law, as to the validity of the decision by Electoral Commissioner O'Shea to register the party – in which proof had been only on the balance of probabilities. Chief Justice Paul de Jersey, with whom the other two judges agreed overall, suggested that if Hanson, Ettridge and especially the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions had used better lawyers from the start, the whole matter might not have taken so long up to the appeal hearing, or might even have been avoided altogether. The Court of Appeal president, Margaret McMurdo, rebuked many politicians, including John Howard and Bronwyn Bishop MHR. Their observations, she said, demonstrated at least "a lack of understanding of the Rule of Law" and "an attempt to influence the judicial appellate process and to interfere with the independence of the judiciary for cynical political motives", although she praised other leading Coalition politicians for accepting the District Court's decision.[158]

Television appearances

In 2004, Hanson appeared in multiple television programs such as Dancing with the Stars, Enough Rope, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire and This is Your Life.[159]

In 2011, Hanson was a contestant on Celebrity Apprentice.[160]

Following her successful relaunch of Pauline Hanson's One Nation party at the 2016 federal Senate election, with four senators elected, including herself, a documentary was made by the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) entitled Pauline Hanson: Please Explain![161]

Sexual harassment allegations

On 14 February 2019, Hanson was accused of sexually harassing fellow Senator Brian Burston.[162] Burston claimed that Hanson "rubbed her fingers up my spine" in an incident that occurred in 1998, and propositioned him after he was elected in 2016.[163] In court it arose Hanson also sent a "malicious" text message to Burston's wife claiming he was infatuated with another staff member.[164] Hanson has denied the claims of sexual harassment.[165]

Published books

Soon after her election to Parliament, Hanson's book Pauline Hanson—the Truth: on Asian immigration, the Aboriginal question, the gun debate and the future of Australia was published. In it she makes claims of Aboriginal cannibalism, in particular that Aboriginal women ate their babies and tribes cannibalised their members. Hanson told the media that the reason for these claims of cannibalism was to "demonstrate the savagery of Aboriginal society".[166]

David Ettridge, the One Nation party director, said that the book's claims were intended to correct "misconceptions" about Aboriginal history. These alleged misconceptions were said to be relevant to modern-day Aboriginal welfare funding. He asserted that "the suggestion that we should be feeling some concern for modern day Aborigines for suffering in the past is balanced a bit by the alternative view of whether you can feel sympathy for people who eat their babies".[167] The book predicted that in 2050 Australia would have a lesbian president of Chinese-Indian background called Poona Li Hung who would be a cyborg.[168] In 2004, Hanson said that the book was "written by some other people who actually put my name to it" and that, while she held the copyright in the book, she was unaware that much of the material was being published under her name.[10]

In March 2007, Hanson published her autobiography, Untamed and Unashamed.[169][170]

In 2018, Hanson and Tony Abbott launched a collection of Hanson's speeches, Pauline: In Her Own Words, compiled by journalist Tom Ravlic.[171]

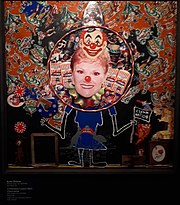

In art

Aboriginal artist Karla Dickens represented Hanson in a collage entitled "Clown Nation" which included Hanson's photograph, in a series called A Dickensian Country Show. It was shown in the 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia, an exhibition titled "Monster Theatres".[172]

References

- ^ a b "History – Pauline Hanson's One Nation". Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ a b c "The rise and fall of Pauline Hanson". 20 August 2003. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Pauline Hanson's bitter harvest". 16 September 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ "Ipswich City Council - Divisional Boundaries" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ "Councillors Of Ipswich 1860–2005 – Chronological List" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Rosemary Francis (22 April 2009). "Hanson, Pauline Lee (1954 – )". The Australian Women's Register. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ Hanson, Pauline (2007). Untamed & Unashamed. p. 34.

- ^ "Senators and Members, by Date of Birth". Parliament of Australia, Parliamentary Library. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ^ "ParlInfo – Biography for HANSON, Pauline Lee". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ a b c "ENOUGH ROPE with Andrew Denton – episode 60: Pauline Hanson (20/09/2004)". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 20 September 2004. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ Gould, Joel (24 January 2015). "Hanson back to where it all began at old fish and chip shop". The Queensland Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Tony Moore (7 July 2016). "The rise and fall and rise of Pauline Hanson". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ Green, Antony (20 March 2018). "What Happens if a Candidate Withdraws from a Contest?". ABC. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Liberal candidate Kevin Baker quits race for Charlton over lewd website Archived 31 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ABC News, 20 August 2013.

- ^ "Commonwealth Of Australia - Legislative Election Of 2 March 1996". Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Ward, Ian (December 1996), "Australian Political Chronicle: January–June 1996", Australian Journal of Politics and History, 42 (3): 402–408, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1996.tb01372.x

- ^ a b Pauline Hanson, Member for Oxley (10 September 1996). "APPROPRIATION BILL (No. 1) 1996–97 Second Reading". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives. p. 3859. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018.

- ^ "Pauline Hanson: One Nation party's resurgence after 20 years of controversy – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 11 July 2016. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ a b Ward, Ian (December 1997), "Australian Political Chronicle: January–June 1997", Australian Journal of Politics and History, 43 (3): 374

- ^ Scalmer, Sean (2001). Dissent Events: Protest, the Media, and the Political Gimmick in Australia. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-0868406510.

- ^ Kelly, Paul (2000). Paradise Divided: The Changes, the Challenges, the Choices for Australia. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. pp. 143–144. ISBN 1-86508-291-0.

- ^ Emerson, Scott (24 March 1999). "One Nation loses its heartland". The Australian. p. 6.

- ^ Penberthy, David (17 October 1998). "Outcasts asunder". The Advertiser. p. 58.

- ^ Scott, Leisa (5 October 1998). "It's my party and I'll cry if I want to / ONE NATION". The Australian. p. 3.

- ^ a b Poll Bludger review of Blair Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine for 2016 federal election

- ^ Green, Antony. 2010 election preview: Queensland Archived 19 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine. ABC News, 2010.

- ^ Goot, Murray. Pauline Hanson's One Nation: Extreme Right, Centre Party or Extreme Left? Labour History, No. 89, Nov 2005: 101–119. ISSN 0023-6942.

- ^ a b c "Federal Elections 1998 (Research Paper 9 1998–99)". Aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Bruce (January 2003). "Two Paulines, Two Nations: An Australian Case Study in the Intersection of Popular Music and Politics". Popular Music and Society. 26 (1): 53–72. doi:10.1080/0300776032000076397. S2CID 144202972.

- ^ "(Research Paper 8 1998–99)". Aph.gov.au. 27 September 2001. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Sue v Hill [1999] HCA 30, (1999) 199 CLR 462, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Constitution (Cth) s 44 Disqualification.

- ^ "Howard knew of slush fund to target Hanson". News Online. 27 August 2003. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010.

- ^ "Abbot denies lying over anti-Hanson fund". News Online. Lateline (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). 27 August 2003. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Honest Tony's too up front, says PM". The Sydney Morning Herald. 28 August 2003. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Seccombe, Mike; Murphy, Damien (28 August 2003). "Watchdog rethinks Liberal links to Abbott's slush fund". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Pauline Hanson pulls the plug as One Nation president". ABC. 14 January 2002. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Ward, Ian (August 1997), "Australian Political Chronicle: June–December 1996", Australian Journal of Politics and History, 43 (2): 216–224, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1997.tb01389.x

- ^ a b "It's porridge for Pauline". The Age. Melbourne. 20 August 2003. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Hanson rules out return to politics". The Age. Melbourne. 16 January 2004. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ a b Australian Electoral Commission (9 November 2005). "First Preferences by Candidate – Queensland". Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ "Top payout for running". The Northern Times. 15 October 2004. p. 12.

- ^ Strutt, Sam (27 December 2007). "Hanson will party on Back under a new name in new year". Herald Sun. p. 13.

- ^ Hanson election bid will have voters groaning: Bligh Archived 28 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine (ABC, 25 February 2009).

- ^ I'll quit politics, says Hanson Archived 23 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine (Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 2009).

- ^ Hanson defeated, blames hoax photos: The Advertiser Archived 25 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Pauline Hanson considering a return to politics... if Tony Abbott asks her to". News.com.au. 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Nicholls, Sean (8 March 2011). "Pauline Hanson running in NSW election". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "Hanson fails to win seat in NSW". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ "Legislative Council Results". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ "Pauline Hanson misses out on NSW seat in distribution of preferences". The Australian. 12 April 2011. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ "Hanson cries sabotage over 'hidden' votes". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ "Hanson to challenge NSW vote count". The Sydney Morning Herald. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Bennett, Adam (17 May 2011). "Commissioner backs staff in Hanson row". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Wallace, Rick (8 June 2011). "Key witness for Pauline Hanson a no-show". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Knott, Matthew (10 June 2012). "Rattnergate revelation: Hanson's mole was a fraud". crikey.com.au. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Wallace, Rick (23 June 2011). "Hanson hoaxer speaks out: and the trail leads to... Mickey Mouse". crikey.com.au. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Wallace, Rick (14 June 2011). "Pauline Hanson fraudster Shaun Castle admits deception". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Godfrey, Miles (25 June 2011). "Taxpayers hit for Hanson's failed election challenge". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012. Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Pauline_Hanson

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Australian Senate

File:Pauline Hanson 2017 05 (cropped).jpg

Pauline Hanson's One Nation

Pauline Hanson's One Nation

Malcolm Roberts (politician)

Steve Dickson

Brian Burston

James Ashby

Brian Burston

John Fischer (politician)

David Ettridge

David Oldfield (politician)

John Fischer (politician)

List of senators from Queensland

Incumbent

Glenn Lazarus

Pauline's United Australia Party

Brian Burston

Parliament of Australia

Division of Oxley

1996 Australian federal election

1998 Australian federal election

Les Scott

Bernie Ripoll

City of Ipswich

City of Ipswich

Paul Pisasale

Woolloongabba

Queensland

Pauline Hanson's One Nation

Independent (politician)

Liberal Party of Australia

Pauline's United Australia Party

Beaudesert, Queensland

Buranda, Queensland

Coorparoo State School

Small Business

Fish and chip shop

Business administration

Clerk

History of Bickford's Australia#Drug Houses of Australia (1930—1974)

File:Pauline Hanson signature.svg

File:Pauline Hanson 2017 05 (cropped).jpg

Hansonism

Electoral history of Pauline Hanson

Division of Oxley

Pauline Hanson's One Nation#Overview

One Nation NSW

City Country Alliance

New Country Party

Pauline's United Australia Party

Queensland

It's okay to be white#Australian parliament motion

1998 Australian federal election

2001 Australian federal election

2016 Australian federal election

2019 Australian federal election

2022 Australian federal election

Pauline Hanson: Please Explain!

Government of Australia

Template:Pauline Hanson sidebar

Template talk:Pauline Hanson sidebar

Special:EditPage/Template:Pauline Hanson sidebar

Category:Conservatism in Australia

Conservatism in Australia

File:Coat of Arms of Australia.svg

Agrarianism

Australian nationalism

Liberal conservatism

Cultural liberalism

Economic liberalism

One Australia

One-nation conservatism

Federalism in Australia

Free market

Free trade

Limited government

Loyalism

Monarchism

Property rights

Protectionism

Rule of law

Geoffrey Blainey

Peter Coleman

Kevin Donnelly

Owen Harries

Gerard Henderson

Gregory Melleuish

Kenneth Minogue

B. A. Santamaria

David Stove

Keith Windschuttle

James Allan (law professor)

Edmund Barton

Ian Callinan

Greg Craven (academic)

Daryl Dawson

John Finnis

David Flint

Murray Gleeson

Harry Gibbs

Kenneth Hayne

Dyson Heydon

Susan Kiefel

Allan Myers

Simon Steward (judge)

Stuart Wood (lawyer)

Piers Akerman

Janet Albrechtsen

Andrew Bolt

Peta Credlin

Rowan Dean

Frank Devine

Miranda Devine

Ray Hadley

Alan Jones (radio broadcaster)

Chris Kenny

Christian Kerr

Claire Lehmann

Padraic McGuinness

Warren Mundine

Paul Murray (presenter)

Peter van Onselen

Steve Price (broadcaster)

Lyle Shelton (lobbyist)

Amanda Vanstone

Tony Abbott

John Anderson (Australian politician)

Fraser Anning

Edmund Barton

Cory Bernardi

Neville Bonner

Matt Canavan

Joh Bjelke-Petersen

Peter Dutton

Malcolm Fraser

John Gorton

Harold Holt

John Howard

Barnaby Joyce

Bob Katter

Craig Kelly

Joseph Lyons

Robert Menzies

Scott Morrison

Warren Mundine

Campbell Newman

Clive Palmer

Dominic Perrottet

Jacinta Price

George Reid

Amanda Vanstone

Australian Christians (political party)

Democratic Labour Party (Australia, 1980)

Family First Party (2021)

Katter's Australian Party

Liberal Party of Australia

Coalition (Australia)

Liberal National Party of Queensland

Coalition (Australia)

National Party of Australia

Coalition (Australia)

Pauline Hanson's One Nation

Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party

United Australia Party (2013)

Christian Democratic Party (Australia)

Liberal Party (Australia, 1909)

Australian Conservatives

Australian Conservative Party

Fraser Anning's Conservative National Party

Family First Party

Queensland Liberal Party

National Party of Australia – Queensland

National Defence League

Nationalist Party (Australia)

Advance Australia (lobby group)

Australians for Constitutional Monarchy

Australian Christian Lobby

Coalition for Marriage (Australia)

Conservative Political Action Conference#Australia

Cormack Foundation

National Civic Council

Paul Ramsay#Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation

Australian Academy of Art

Australian National Flag Association

Old Guard (Australia)

Centre for Independent Studies

Institute of Public Affairs

Menzies Research Centre

Samuel Griffith Society

H. R. Nicholls Society

ADH TV

The Australian

Counterpoint (Radio National)

The Daily Telegraph (Sydney)

Herald Sun

News Weekly

Quadrant (magazine)

Quilette

Sky News Australia

The Argus (Melbourne)

Conservatism in New Zealand

Moderates (Liberal Party of Australia)

Centre Right (Liberal Party of Australia)

National Right (Liberal Party of Australia)

Liberal conservatism

Liberalism in Australia

Politics of Australia

Portal:Conservatism

Portal:Australia

Template:Conservatism in Australia

Template talk:Conservatism in Australia

Special:EditPage/Template:Conservatism in Australia

Pauline Hanson's One Nation

Right-wing populist

Queensland

Australian Senate

2016 Australian federal election

Fish and chip

City of Ipswich

Liberal Party of Australia

Preselection

Division of Oxley

Brisbane

1996 Australian federal election

Aboriginal Australians

Division of Blair

1998 Australian federal election

1998 Queensland state election

2001 Australian federal election

District Court of Queensland

Supreme Court of Queensland

Pauline's United Australia Party

2015 Queensland state election

2016 Australian federal election

2022 Australian federal election

Woolloongabba, Queensland

Coorparoo State School

Coorparoo, Queensland

Fish and chip shop

Ipswich, Queensland

Office administration

Bookkeeping

Sales ledger

Woolworths Supermarkets

Office administration

History of Bickford's Australia

Drug Houses of Australia

Bickford's Australia

Clerk

Bookkeeping

Secretary

Gold Coast, Queensland

Roofer

Office administration

Silkstone, Queensland

Ipswich, Queensland

Australian Parliament

City of Ipswich

Liberal Party of Australia

House of Representatives (Australia)

Division of Oxley

1996 Australian federal election

Les Scott

Aboriginal Australians

Australian Electoral Commission

John Howard

Australian Democrats

Les Scott

Australian Labor Party

Wikipedia:Reliable sources

Independent politician

Maiden speech

Land rights

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission

Family Law Act 1975

Child support

Qantas

Immigration to Australia

Multiculturalism

Protectionism

Economic rationalism

Pauline Hanson's One Nation

David Oldfield (politician)

David Ettridge

Dandenong, Victoria

City of Greater Dandenong

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission

1967 Australian referendum (Aboriginals)

The Australian

1998 Australian federal election

Redistribution (Australia)

Inala, Queensland

Division of Blair

Wayne Goss

Australian Senate

Ranked voting systems

Cameron Thompson (politician)

Pauline Pantsdown

Len Harris (politician)

Heather Hill (politician)

Section 44 of the Constitution of Australia

Tony Abbott

John Howard

Aboriginal Australians

Centrelink

Multiculturalism

Political correctness

Graeme Campbell (politician)

Censure

Political correctness

Anti-immigration

Citizens' Electoral Council

Australian League of Rights

Phillip Ruddock

File:Pauline Hanson at the Kurri Kurri Nostalgia Festival in 2011.jpg

2001 Australian federal election

Liberal Party of Australia

Updating...x

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.