A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death.[1][2] In most beliefs involving reincarnation, the soul of a human being is immortal and does not disperse after the physical body has perished. Upon death, the soul merely becomes transmigrated into a newborn baby or an animal to continue its immortality. The term transmigration means the passing of a soul from one body to another after death.

Reincarnation (punarjanma) is a central tenet of the Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism; although there are Hindu and Buddhist groups who do not believe in reincarnation, instead believing in an afterlife.[3][4][5][6] In various forms, it occurs as an esoteric belief in many streams of Judaism, certain pagan religions including Wicca, and some beliefs of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas[7] and Indigenous Australians (though most believe in an afterlife or spirit world).[8] A belief in the soul's rebirth or migration (metempsychosis) was expressed by certain ancient Greek historical figures, such as Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato.[9]

Although the majority of denominations within Abrahamic religions do not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and contemporary followers of Cathars, Alawites, Hassidics, the Druze,[10] Kabbalistics and the Rosicrucians.[11] The historical relations between these sects and the beliefs about reincarnation that were characteristic of Neoplatonism, Orphism, Hermeticism, Manichaenism, and Gnosticism of the Roman era as well as the Indian religions have been the subject of recent scholarly research.[12] In recent decades, many Europeans and North Americans have developed an interest in reincarnation,[13] and many contemporary works mention it.

Conceptual definitions

The word reincarnation derives from a Latin term that literally means 'entering the flesh again'. Reincarnation refers to the belief that an aspect of every human being (or all living beings in some cultures) continues to exist after death. This aspect may be the soul, mind, consciousness, or something transcendent which is reborn in an interconnected cycle of existence; the transmigration belief varies by culture, and is envisioned to be in the form of a newly born human being, animal, plant, spirit, or as a being in some other non-human realm of existence.[14][15][16]

An alternative term is transmigration, implying migration from one life (body) to another.[17] The term has been used by modern philosophers such as Kurt Gödel[18] and has entered the English language.

The Greek equivalent to reincarnation, metempsychosis (μετεμψύχωσις), derives from meta ('change') and empsykhoun ('to put a soul into'),[19] a term attributed to Pythagoras.[20] Another Greek term sometimes used synonymously is palingenesis, 'being born again'.[21]

Rebirth is a key concept found in major Indian religions, and discussed using various terms. Reincarnation, or Punarjanman (Sanskrit: पुनर्जन्मन्, 'rebirth, transmigration'),[22][23] is discussed in the ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, with many alternate terms such as punarāvṛtti (पुनरावृत्ति), punarājāti (पुनराजाति), punarjīvātu (पुनर्जीवातु), punarbhava (पुनर्भव), āgati-gati (आगति-गति, common in Buddhist Pali text), nibbattin (निब्बत्तिन्), upapatti (उपपत्ति), and uppajjana (उप्पज्जन).[22][24]

These religions believe that this reincarnation is cyclic and an endless Saṃsāra, unless one gains spiritual insights that ends this cycle leading to liberation.[3][25] The reincarnation concept is considered in Indian religions as a step that starts each "cycle of aimless drifting, wandering or mundane existence",[3] but one that is an opportunity to seek spiritual liberation through ethical living and a variety of meditative, yogic (marga), or other spiritual practices.[26] They consider the release from the cycle of reincarnations as the ultimate spiritual goal, and call the liberation by terms such as moksha, nirvana, mukti and kaivalya.[27][28][29] However, the Buddhist, Hindu and Jain traditions have differed, since ancient times, in their assumptions and in their details on what reincarnates, how reincarnation occurs and what leads to liberation.[30][31]

Gilgul, Gilgul neshamot, or Gilgulei Ha Neshamot (Hebrew: גלגול הנשמות) is the concept of reincarnation in Kabbalistic Judaism, found in much Yiddish literature among Ashkenazi Jews. Gilgul means 'cycle' and neshamot is 'souls'. Kabbalistic reincarnation says that humans reincarnate only to humans unless YHWH/Ein Sof/God chooses.

History

Origins

The origins of the notion of reincarnation are obscure.[32] Discussion of the subject appears in the philosophical traditions of India. The Greek Pre-Socratics discussed reincarnation, and the Celtic druids are also reported to have taught a doctrine of reincarnation.[33]

Early Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism

The concepts of the cycle of birth and death, saṁsāra, and liberation partly derive from ascetic traditions that arose in India around the middle of the first millennium BCE.[34] The first textual references to the idea of reincarnation appear in the Rigveda, Yajurveda and Upanishads of the late Vedic period (c. 1100 – c. 500 BCE), predating the Buddha and Mahavira.[35][36] Though no direct evidence of this has been found, the tribes of the Ganges valley or the Dravidian traditions of South India have been proposed as another early source of reincarnation beliefs.[37]

The idea of reincarnation, saṁsāra, did exist in the early Vedic religions.[38][39][40] The early Vedas does mention the doctrine of karma and rebirth.[25][41][42] It is in the early Upanishads, which are pre-Buddha and pre-Mahavira, where these ideas are developed and described in a general way.[43][44][45] Detailed descriptions first appear around the mid-1st millennium BCE in diverse traditions, including Buddhism, Jainism and various schools of Hindu philosophy, each of which gave unique expression to the general principle.[25]

Sangam literature[46] connotes the ancient Tamil literature and is the earliest known literature of South India. The Tamil tradition and legends link it to three literary gatherings around Madurai. According to Kamil Zvelebil, a Tamil literature and history scholar, the most acceptable range for the Sangam literature is 100 BCE to 250 CE, based on the linguistic, prosodic and quasi-historic allusions within the texts and the colophons.[47] There are several mentions of rebirth and moksha in the Purananuru.[48] The text explains Hindu rituals surrounding death such as making riceballs called pinda and cremation. The text states that good souls get a place in Indraloka where Indra welcomes them.[49]

The texts of ancient Jainism that have survived into the modern era are post-Mahavira, likely from the last centuries of the first millennium BCE, and extensively mention rebirth and karma doctrines.[50][51] The Jaina philosophy assumes that the soul (jiva in Jainism; atman in Hinduism) exists and is eternal, passing through cycles of transmigration and rebirth.[52] After death, reincarnation into a new body is asserted to be instantaneous in early Jaina texts.[51] Depending upon the accumulated karma, rebirth occurs into a higher or lower bodily form, either in heaven or hell or earthly realm.[53][54] No bodily form is permanent: everyone dies and reincarnates further. Liberation (kevalya) from reincarnation is possible, however, through removing and ending karmic accumulations to one's soul.[55] From the early stages of Jainism on, a human being was considered the highest mortal being, with the potential to achieve liberation, particularly through asceticism.[56][57][58]

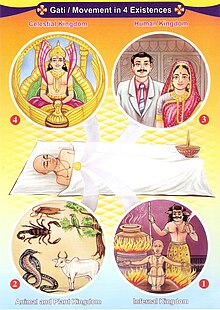

The early Buddhist texts discuss rebirth as part of the doctrine of saṃsāra. This asserts that the nature of existence is a "suffering-laden cycle of life, death, and rebirth, without beginning or end".[59][60] Also referred to as the wheel of existence (Bhavacakra), it is often mentioned in Buddhist texts with the term punarbhava (rebirth, re-becoming). Liberation from this cycle of existence, Nirvana, is the foundation and the most important purpose of Buddhism.[59][61][62] Buddhist texts also assert that an enlightened person knows his previous births, a knowledge achieved through high levels of meditative concentration.[63] Tibetan Buddhism discusses death, bardo (an intermediate state), and rebirth in texts such as the Tibetan Book of the Dead. While Nirvana is taught as the ultimate goal in the Theravadin Buddhism, and is essential to Mahayana Buddhism, the vast majority of contemporary lay Buddhists focus on accumulating good karma and acquiring merit to achieve a better reincarnation in the next life.[64][65]

In early Buddhist traditions, saṃsāra cosmology consisted of five realms through which the wheel of existence cycled.[59] This included hells (niraya), hungry ghosts (pretas), animals (tiryaka), humans (manushya), and gods (devas, heavenly).[59][60][66] In latter Buddhist traditions, this list grew to a list of six realms of rebirth, adding demigods (asuras).[59][67]

Rationale

The earliest layers of Vedic text incorporate the concept of life, followed by an afterlife in heaven and hell based on cumulative virtues (merit) or vices (demerit).[68] However, the ancient Vedic rishis challenged this idea of afterlife as simplistic, because people do not live equally moral or immoral lives. Between generally virtuous lives, some are more virtuous; while evil too has degrees, and the texts assert that it would be unfair for people, with varying degrees of virtue or vices, to end up in heaven or hell, in "either or" and disproportionate manner irrespective of how virtuous or vicious their lives were.[69][70][71] They introduced the idea of an afterlife in heaven or hell in proportion to one's merit.[72][73][74]

Comparison

Early texts of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism share the concepts and terminology related to reincarnation.[75] They also emphasize similar virtuous practices and karma as necessary for liberation and what influences future rebirths.[35][76] For example, all three discuss various virtues—sometimes grouped as Yamas and Niyamas—such as non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, non-possessiveness, compassion for all living beings, charity and many others.[77][78]

Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism disagree in their assumptions and theories about rebirth. Hinduism relies on its foundational assumption that 'soul, Self exists' (atman or attā), in contrast to Buddhist assumption that there is 'no soul, no Self' (anatta or anatman).[79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88] Hindu traditions consider soul to be the unchanging eternal essence of a living being, and what journeys across reincarnations until it attains self-knowledge.[89][90][91] Buddhism, in contrast, asserts a rebirth theory without a Self, and considers realization of non-Self or Emptiness as Nirvana (nibbana). Thus Buddhism and Hinduism have a very different view on whether a self or soul exists, which impacts the details of their respective rebirth theories.[92][93][94]

The reincarnation doctrine in Jainism differs from those in Buddhism, even though both are non-theistic Sramana traditions.[95][96] Jainism, in contrast to Buddhism, accepts the foundational assumption that soul exists (Jiva) and asserts this soul is involved in the rebirth mechanism.[97] Further, Jainism considers asceticism as an important means to spiritual liberation that ends all reincarnation, while Buddhism does not.[95][98][99]

Classical antiquity

Early Greek discussion of the concept dates to the sixth century BCE. An early Greek thinker known to have considered rebirth is Pherecydes of Syros (fl. 540 BCE).[100] His younger contemporary Pythagoras (c. 570–c. 495 BCE[101]), its first famous exponent, instituted societies for its diffusion. Some authorities believe that Pythagoras was Pherecydes' pupil, others that Pythagoras took up the idea of reincarnation from the doctrine of Orphism, a Thracian religion, or brought the teaching from India.

Plato (428/427–348/347 BCE) presented accounts of reincarnation in his works, particularly the Myth of Er, where Plato makes Socrates tell how Er, the son of Armenius, miraculously returned to life on the twelfth day after death and recounted the secrets of the other world. There are myths and theories to the same effect in other dialogues, in the Chariot allegory of the Phaedrus,[102] in the Meno,[103] Timaeus and Laws. The soul, once separated from the body, spends an indeterminate amount of time in the intelligible realm (see The Allegory of the Cave in The Republic) and then assumes another body. In the Timaeus, Plato believes that the soul moves from body to body without any distinct reward-or-punishment phase between lives, because the reincarnation is itself a punishment or reward for how a person has lived.[104]

In Phaedo, Plato has his teacher Socrates, prior to his death, state: "I am confident that there truly is such a thing as living again, and that the living spring from the dead." However, Xenophon does not mention Socrates as believing in reincarnation, and Plato may have systematized Socrates' thought with concepts he took directly from Pythagoreanism or Orphism. Recent scholars have come to see that Plato has multiple reasons for the belief in reincarnation.[105] One argument concerns the theory of reincarnation's usefulness for explaining why non-human animals exist: they are former humans, being punished for their vices; Plato gives this argument at the end of the Timaeus.[106]

Mystery cults

The Orphic religion, which taught reincarnation, about the sixth century BCE, produced a copious literature.[107][108][109] Orpheus, its legendary founder, is said to have taught that the immortal soul aspires to freedom while the body holds it prisoner. The wheel of birth revolves, the soul alternates between freedom and captivity round the wide circle of necessity. Orpheus proclaimed the need of the grace of the gods, Dionysus in particular, and of self-purification until the soul has completed the spiral ascent of destiny to live forever.

An association between Pythagorean philosophy and reincarnation was routinely accepted throughout antiquity, as Pythagoras also taught about reincarnation. However, unlike the Orphics, who considered metempsychosis a cycle of grief that could be escaped by attaining liberation from it, Pythagoras seems to postulate an eternal, neutral reincarnation where subsequent lives would not be conditioned by any action done in the previous.[110]

Later authors

In later Greek literature the doctrine is mentioned in a fragment of Menander[111] and satirized by Lucian.[112] In Roman literature it is found as early as Ennius,[113] who, in a lost passage of his Annals, told how he had seen Homer in a dream, who had assured him that the same soul which had animated both the poets had once belonged to a peacock. Persius in his satires (vi. 9) laughs at this; it is referred to also by Lucretius[114] and Horace.[115]

Virgil works the idea into his account of the Underworld in the sixth book of the Aeneid.[116] It persists down to the late classic thinkers, Plotinus and the other Neoplatonists. In the Hermetica, a Graeco-Egyptian series of writings on cosmology and spirituality attributed to Hermes Trismegistus/Thoth, the doctrine of reincarnation is central.

Celtic paganism

In the first century BCE Alexander Cornelius Polyhistor wrote:

The Pythagorean doctrine prevails among the Gauls' teaching that the souls of men are immortal, and that after a fixed number of years they will enter into another body.

Julius Caesar recorded that the druids of Gaul, Britain and Ireland had metempsychosis as one of their core doctrines:[117]

The principal point of their doctrine is that the soul does not die and that after death it passes from one body into another... the main object of all education is, in their opinion, to imbue their scholars with a firm belief in the indestructibility of the human soul, which, according to their belief, merely passes at death from one tenement to another; for by such doctrine alone, they say, which robs death of all its terrors, can the highest form of human courage be developed.

Diodorus also recorded the Gaul belief that human souls were immortal, and that after a prescribed number of years they would commence upon a new life in another body. He added that Gauls had the custom of casting letters to their deceased upon the funeral pyres, through which the dead would be able to read them.[118] Valerius Maximus also recounted they had the custom of lending sums of money to each other which would be repayable in the next world.[119] This was mentioned by Pomponius Mela, who also recorded Gauls buried or burnt with them things they would need in a next life, to the point some would jump into the funeral piles of their relatives in order to cohabit in the new life with them.[120]

Hippolytus of Rome believed the Gauls had been taught the doctrine of reincarnation by a slave of Pythagoras named Zalmoxis. Conversely, Clement of Alexandria believed Pythagoras himself had learned it from the Celts and not the opposite, claiming he had been taught by Galatian Gauls, Hindu priests and Zoroastrians.[121][122] However, author T. D. Kendrick rejected a real connection between Pythagoras and the Celtic idea reincarnation, noting their beliefs to have substantial differences, and any contact to be historically unlikely.[120] Nonetheless, he proposed the possibility of an ancient common source, also related to the Orphic religion and Thracian systems of belief.[123]

Germanic paganism

Surviving texts indicate that there was a belief in rebirth in Germanic paganism. Examples include figures from eddic poetry and sagas, potentially by way of a process of naming and/or through the family line. Scholars have discussed the implications of these attestations and proposed theories regarding belief in reincarnation among the Germanic peoples prior to Christianization and potentially to some extent in folk belief thereafter.

Judaism

The belief in reincarnation developed among Jewish mystics in the medieval world, among whom differing explanations were given of the afterlife, although with a universal belief in an immortal soul.[124] It was explicitly rejected by Saadiah Gaon.[125] Today, reincarnation is an esoteric belief within many streams of modern Judaism. Kabbalah teaches a belief in gilgul, transmigration of souls, and hence the belief in reincarnation is universal in Hasidic Judaism, which regards the Kabbalah as sacred and authoritative, and is also sometimes held as an esoteric belief within other strains of Orthodox Judaism. In Judaism, the Zohar, first published in the 13th century, discusses reincarnation at length, especially in the Torah portion "Balak." The most comprehensive kabbalistic work on reincarnation, Shaar HaGilgulim,[126][127] was written by Chaim Vital, based on the teachings of his mentor, the 16th-century kabbalist Isaac Luria, who was said to know the past lives of each person through his semi-prophetic abilities. The 18th-century Lithuanian master scholar and kabbalist, Elijah of Vilna, known as the Vilna Gaon, authored a commentary on the biblical Book of Jonah as an allegory of reincarnation.

The practice of conversion to Judaism is sometimes understood within Orthodox Judaism in terms of reincarnation. According to this school of thought in Judaism, when non-Jews are drawn to Judaism, it is because they had been Jews in a former life. Such souls may "wander among nations" through multiple lives, until they find their way back to Judaism, including through finding themselves born in a gentile family with a "lost" Jewish ancestor.[128]

There is an extensive literature of Jewish folk and traditional stories that refer to reincarnation.[129]

Christianity

Reincarnationism or biblical reincarnation is the belief that certain people are or can be reincarnations of biblical figures, such as Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary.[130] Some Christians believe that certain New Testament figures are reincarnations of Old Testament figures. For example, John the Baptist is believed by some to be a reincarnation of the prophet Elijah, and a few take this further by suggesting Jesus was the reincarnation of Elijah's disciple Elisha.[130][131] Other Christians believe the Second Coming of Jesus would be fulfilled by reincarnation. Sun Myung Moon, the founder of the Unification Church, considered himself to be the fulfillment of Jesus' return.

The Catholic Church does not believe in reincarnation, which it regards as being incompatible with death.[132] Nonetheless, the leaders of certain sects in the church have taught that they are reincarnations of Mary - for example, Marie-Paule Giguère of the Army of Mary[133][134] and Maria Franciszka of the former Mariavites.[135] The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith excommunicated the Army of Mary for teaching heresy, including reincarnationism.[136]

Gnosticism

Several Gnostic sects professed reincarnation. The Sethians and followers of Valentinus believed in it.[137] The followers of Bardaisan of Mesopotamia, a sect of the second century deemed heretical by the Catholic Church, drew upon Chaldean astrology, to which Bardaisan's son Harmonius, educated in Athens, added Greek ideas including a sort of metempsychosis. Another such teacher was Basilides (132–? CE/AD), known to us through the criticisms of Irenaeus and the work of Clement of Alexandria (see also Neoplatonism and Gnosticism and Buddhism and Gnosticism).

In the third Christian century Manichaeism spread both east and west from Babylonia, then within the Sassanid Empire, where its founder Mani lived about 216–276. Manichaean monasteries existed in Rome in 312 AD. Noting Mani's early travels to the Kushan Empire and other Buddhist influences in Manichaeism, Richard Foltz[138] attributes Mani's teaching of reincarnation to Buddhist influence. However the inter-relation of Manicheanism, Orphism, Gnosticism and neo-Platonism is far from clear.

Taoism

Taoist documents from as early as the Han Dynasty claimed that Lao Tzu appeared on earth as different persons in different times beginning in the legendary era of Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors. The (ca. third century BC) Chuang Tzu states: "Birth is not a beginning; death is not an end. There is existence without limitation; there is continuity without a starting-point. Existence without limitation is Space. Continuity without a starting point is Time. There is birth, there is death, there is issuing forth, there is entering in."[139][better source needed]

European Middle Ages

Around the 11–12th century in Europe, several reincarnationist movements were persecuted as heresies, through the establishment of the Inquisition in the Latin west. These included the Cathar, Paterene or Albigensian church of western Europe, the Paulician movement, which arose in Armenia,[140] and the Bogomils in Bulgaria.[141]

Christian sects such as the Bogomils and the Cathars, who professed reincarnation and other gnostic beliefs, were referred to as "Manichaean", and are today sometimes described by scholars as "Neo-Manichaean".[142] As there is no known Manichaean mythology or terminology in the writings of these groups there has been some dispute among historians as to whether these groups truly were descendants of Manichaeism.[143]

Renaissance and Early Modern period

While reincarnation has been a matter of faith in some communities from an early date it has also frequently been argued for on principle, as Plato does when he argues that the number of souls must be finite because souls are indestructible,[144] Benjamin Franklin held a similar view.[145] Sometimes such convictions, as in Socrates' case, arise from a more general personal faith, at other times from anecdotal evidence such as Plato makes Socrates offer in the Myth of Er.

During the Renaissance translations of Plato, the Hermetica and other works fostered new European interest in reincarnation. Marsilio Ficino[146] argued that Plato's references to reincarnation were intended allegorically, Shakespeare alluded to the doctrine of reincarnation[147] but Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake by authorities after being found guilty of heresy by the Roman Inquisition for his teachings.[148] But the Greek philosophical works remained available and, particularly in north Europe, were discussed by groups such as the Cambridge Platonists. Emanuel Swedenborg believed that we leave the physical world once, but then go through several lives in the spiritual world—a kind of hybrid of Christian tradition and the popular view of reincarnation.[149]

19th to 20th centuries

By the 19th century the philosophers Schopenhauer[151] and Nietzsche[152] could access the Indian scriptures for discussion of the doctrine of reincarnation, which recommended itself to the American Transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson and was adapted by Francis Bowen into Christian Metempsychosis.[153]

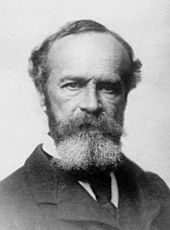

By the early 20th century, interest in reincarnation had been introduced into the nascent discipline of psychology, largely due to the influence of William James, who raised aspects of the philosophy of mind, comparative religion, the psychology of religious experience and the nature of empiricism.[154] James was influential in the founding of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) in New York City in 1885, three years after the British Society for Psychical Research (SPR) was inaugurated in London,[150] leading to systematic, critical investigation of paranormal phenomena. Famous World War II American General George Patton was a strong believer in reincarnation, believing, among other things, he was a reincarnation of the Carthaginian General Hannibal.

At this time popular awareness of the idea of reincarnation was boosted by the Theosophical Society's dissemination of systematised and universalised Indian concepts and also by the influence of magical societies like The Golden Dawn. Notable personalities like Annie Besant, W. B. Yeats and Dion Fortune made the subject almost as familiar an element of the popular culture of the west as of the east. By 1924 the subject could be satirised in popular children's books.[155] Humorist Don Marquis created a fictional cat named Mehitabel who claimed to be a reincarnation of Queen Cleopatra.[156]

Théodore Flournoy was among the first to study a claim of past-life recall in the course of his investigation of the medium Hélène Smith, published in 1900, in which he defined the possibility of cryptomnesia in such accounts.[157] Carl Gustav Jung, like Flournoy based in Switzerland, also emulated him in his thesis based on a study of cryptomnesia in psychism. Later Jung would emphasise the importance of the persistence of memory and ego in psychological study of reincarnation: "This concept of rebirth necessarily implies the continuity of personality... (that) one is able, at least potentially, to remember that one has lived through previous existences, and that these existences were one's own...."[153] Hypnosis, used in psychoanalysis for retrieving forgotten memories, was eventually tried as a means of studying the phenomenon of past life recall.

More recently, many people in the West have developed an interest in and acceptance of reincarnation.[13] Many new religious movements include reincarnation among their beliefs, e.g. modern Neopagans, Spiritism, Astara,[158] Dianetics, and Scientology. Many esoteric philosophies also include reincarnation, e.g. Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Kabbalah, and Gnostic and Esoteric Christianity such as the works of Martinus Thomsen.

Demographic survey data from 1999 to 2002 shows a significant minority of people from Europe (22%) and America (20%) believe in the existence of life before birth and after death, leading to a physical rebirth.[13][159] The belief in reincarnation is particularly high in the Baltic countries, with Lithuania having the highest figure for the whole of Europe, 44%, while the lowest figure is in East Germany, 12%.[13] A quarter of U.S. Christians, including 10% of all born again Christians, embrace the idea.[160]

Academic psychiatrist and believer in reincarnation, Ian Stevenson, reported that belief in reincarnation is held (with variations in details) by adherents of almost all major religions except Christianity and Islam. In addition, between 20 and 30 percent of persons in western countries who may be nominal Christians also believe in reincarnation.[161] One 1999 study by Walter and Waterhouse reviewed the previous data on the level of reincarnation belief and performed a set of thirty in-depth interviews in Britain among people who did not belong to a religion advocating reincarnation.[162] The authors reported that surveys have found about one fifth to one quarter of Europeans have some level of belief in reincarnation, with similar results found in the USA. In the interviewed group, the belief in the existence of this phenomenon appeared independent of their age, or the type of religion that these people belonged to, with most being Christians. The beliefs of this group also did not appear to contain any more than usual of "new age" ideas (broadly defined) and the authors interpreted their ideas on reincarnation as "one way of tackling issues of suffering", but noted that this seemed to have little effect on their private lives.

Waterhouse also published a detailed discussion of beliefs expressed in the interviews.[163] She noted that although most people "hold their belief in reincarnation quite lightly" and were unclear on the details of their ideas, personal experiences such as past-life memories and near-death experiences had influenced most believers, although only a few had direct experience of these phenomena. Waterhouse analyzed the influences of second-hand accounts of reincarnation, writing that most of the people in the survey had heard other people's accounts of past-lives from regression hypnosis and dreams and found these fascinating, feeling that there "must be something in it" if other people were having such experiences.

Other influential contemporary figures that have written on reincarnation include Alice Ann Bailey, one of the first writers to use the terms New Age and age of Aquarius, Torkom Saraydarian, an Armenian-American musician and religious author, Dolores Cannon, Atul Gawande, Michael Newton, Bruce Greyson, Raymond Moody and Unity Church founder Charles Fillmore.[164] Neale Donald Walsch, an American author of the series Conversations with God claims that he has reincarnated more than 600 times.[165] The Indian spiritual teacher Meher Baba who had significant following in the West taught that reincarnation followed from human desire and ceased once a person was freed from desire.[166]

Religions and philosophies

Buddhism

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

According to various Buddhist scriptures, Gautama Buddha believed in the existence of an afterlife in another world and in reincarnation,

Since there actually is another world (any world other than the present human one, i.e. different rebirth realms), one who holds the view 'there is no other world' has wrong view...

— Buddha, Majjhima Nikaya i.402, Apannaka Sutta, translated by Peter Harvey[167]

The Buddha also asserted that karma influences rebirth, and that the cycles of repeated births and deaths are endless.[167][168] Before the birth of Buddha, ancient Indian scholars had developed competing theories of afterlife, including the materialistic school such as Charvaka,[169] which posited that death is the end, there is no afterlife, no soul, no rebirth, no karma, and they described death to be a state where a living being is completely annihilated, dissolved.[170] Buddha rejected this theory, adopted the alternative existing theories on rebirth, criticizing the materialistic schools that denied rebirth and karma, states Damien Keown.[171] Such beliefs are inappropriate and dangerous, stated Buddha, because such annihilationism views encourage moral irresponsibility and material hedonism;[172] he tied moral responsibility to rebirth.[167][171]

The Buddha introduced the concept that there is no permanent self (soul), and this central concept in Buddhism is called anattā.[173][174][175] Major contemporary Buddhist traditions such as Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions accept the teachings of Buddha. These teachings assert there is rebirth, there is no permanent self and no irreducible ātman (soul) moving from life to another and tying these lives together, there is impermanence, that all compounded things such as living beings are aggregates dissolve at death, but every being reincarnates.[176][177][178] The rebirth cycles continue endlessly, states Buddhism, and it is a source of duhkha (suffering, pain), but this reincarnation and duhkha cycle can be stopped through nirvana. The anattā doctrine of Buddhism is a contrast to Hinduism, the latter asserting that "soul exists, it is involved in rebirth, and it is through this soul that everything is connected".[179][180][181]

Different traditions within Buddhism have offered different theories on what reincarnates and how reincarnation happens. One theory suggests that it occurs through consciousness (Sanskrit: vijñāna; Pali: samvattanika-viññana)[182][183] or stream of consciousness (Sanskrit: citta-santāna, vijñāna-srotām, or vijñāna-santāna; Pali: viññana-sotam)[184] upon death, which reincarnates into a new aggregation. This process, states this theory, is similar to the flame of a dying candle lighting up another.[185][186] The consciousness in the newly born being is neither identical to nor entirely different from that in the deceased but the two form a causal continuum or stream in this Buddhist theory. Transmigration is influenced by a being's past karma (Pali: kamma).[187][188] The root cause of rebirth, states Buddhism, is the abiding of consciousness in ignorance (Sanskrit: avidya; Pali: avijja) about the nature of reality, and when this ignorance is uprooted, rebirth ceases.[189]

Buddhist traditions also vary in their mechanistic details on rebirth. Most Theravada Buddhists assert that rebirth is immediate while the Tibetan and most Chinese and Japanese schools hold to the notion of a bardo (intermediate state) that can last up to 49 days.[190][191] The bardo rebirth concept of Tibetan Buddhism, originally developed in India but spread to Tibet and other Buddhist countries, and involves 42 peaceful deities, and 58 wrathful deities.[192] These ideas led to maps on karma and what form of rebirth one takes after death, discussed in texts such as The Tibetan Book of the Dead.[193][194] The major Buddhist traditions accept that the reincarnation of a being depends on the past karma and merit (demerit) accumulated, and that there are six realms of existence in which the rebirth may occur after each death.[195][15][64]

Within Japanese Zen, reincarnation is accepted by some, but rejected by others. A distinction can be drawn between 'folk Zen', as in the Zen practiced by devotional lay people, and 'philosophical Zen'. Folk Zen generally accepts the various supernatural elements of Buddhism such as rebirth. Philosophical Zen, however, places more emphasis on the present moment.[196][197]

Some schools conclude that karma continues to exist and adhere to the person until it works out its consequences. For the Sautrantika school, each act "perfumes" the individual or "plants a seed" that later germinates. Tibetan Buddhism stresses the state of mind at the time of death. To die with a peaceful mind will stimulate a virtuous seed and a fortunate rebirth; a disturbed mind will stimulate a non-virtuous seed and an unfortunate rebirth.[198]

Christianity

In a survey by the Pew Forum in 2009, 22% of American Christians expressed a belief in reincarnation,[199] and in a 1981 survey 31% of regular churchgoing European Catholics expressed a belief in reincarnation.[200]

Some Christian theologians interpret certain Biblical passages as referring to reincarnation. These passages include the questioning of Jesus as to whether he is Elijah, John the Baptist, Jeremiah, or another prophet (Matthew 16:13–15 and John 1:21–22) and, less clearly (while Elijah was said not to have died, but to have been taken up to heaven), John the Baptist being asked if he is not Elijah (John 1:25).[201][202][203] Geddes MacGregor, an Episcopalian priest and professor of philosophy, has made a case for the compatibility of Christian doctrine and reincarnation.[204]

Early

There is evidence[205][206] that Origen, a Church father in early Christian times, taught reincarnation in his lifetime but that when his works were translated into Latin these references were concealed. One of the epistles written by St. Jerome, "To Avitus" (Letter 124; Ad Avitum. Epistula CXXIV),[207] which asserts that Origen's On the First Principles (Latin: De Principiis; Greek: Περὶ Ἀρχῶν)[208] was mistranscribed:

About ten years ago that saintly man Pammachius sent me a copy of a certain person's rendering, or rather misrendering, of Origen's First Principles; with a request that in a Latin version I should give the true sense of the Greek and should set down the writer's words for good or for evil without bias in either direction. When I did as he wished and sent him the book, he was shocked to read it and locked it up in his desk lest being circulated it might wound the souls of many.[206]

Under the impression that Origen was a heretic like Arius, St. Jerome criticizes ideas described in On the First Principles. Further in "To Avitus" (Letter 124), St. Jerome writes about "convincing proof" that Origen teaches reincarnation in the original version of the book:

The following passage is a convincing proof that he holds the transmigration of the souls and annihilation of bodies. 'If it can be shown that an incorporeal and reasonable being has life in itself independently of the body and that it is worse off in the body than out of it; then beyond a doubt bodies are only of secondary importance and arise from time to time to meet the varying conditions of reasonable creatures. Those who require bodies are clothed with them, and contrariwise, when fallen souls have lifted themselves up to better things, their bodies are once more annihilated. They are thus ever vanishing and ever reappearing.'[206]

The original text of On First Principles has almost completely disappeared. It remains extant as De Principiis in fragments faithfully translated into Latin by St. Jerome and in "the not very reliable Latin translation of Rufinus."[208]

Reincarnation was also taught by several gnostics such as Marcion of Sinope.[209] Belief in reincarnation was rejected by Augustine of Hippo in The City of God.[210]

Druzeedit

| Part of a series on

Druze |

|---|

|

Reincarnation is a paramount tenet in the Druze faith.[211] There is an eternal duality of the body and the soul and it is impossible for the soul to exist without the body. Therefore, reincarnations occur instantly at one's death. While in the Hindu and Buddhist belief system a soul can be transmitted to any living creature, in the Druze belief system this is not possible and a human soul will only transfer to a human body. Furthermore, souls cannot be divided into different or separate parts and the number of souls existing is finite.[212]

Few Druzes are able to recall their past but, if they are able to they are called a Nateq. Typically souls who have died violent deaths in their previous incarnation will be able to recall memories. Since death is seen as a quick transient state, mourning is discouraged.[212] Unlike other Abrahamic faiths, heaven and hell are spiritual. Heaven is the ultimate happiness received when soul escapes the cycle of rebirths and reunites with the Creator, while hell is conceptualized as the bitterness of being unable to reunite with the Creator and escape from the cycle of rebirth.[213]

Hinduismedit

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

Zdroj: Wikipedia.org - čítajte viac o Reincarnationism

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. |