A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolution is a necessary precondition for transitioning from a capitalist to a socialist mode of production. Revolution is not necessarily defined as a violent insurrection; it is defined as a seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so that the state is directly controlled or abolished by the working class as opposed to the capitalist class and its interests.[1]

Revolutionary socialists believe such a state of affairs is a precondition for establishing socialism and orthodox Marxists believe it is inevitable but not predetermined. Revolutionary socialism encompasses multiple political and social movements that may define "revolution" differently from one another. These include movements based on orthodox Marxist theory such as De Leonism, impossibilism and Luxemburgism, as well as movements based on Leninism and the theory of vanguardist-led revolution such as the Stalinism, Maoism, Marxism–Leninism and Trotskyism. Revolutionary socialism also includes other Marxist, Marxist-inspired and non-Marxist movements such as those found in democratic socialism, revolutionary syndicalism, anarchism and social democracy.[2]

Revolutionary socialism is contrasted with reformist socialism, especially the reformist wing of social democracy and other evolutionary approaches to socialism. Revolutionary socialism is opposed to social movements that seek to gradually ameliorate capitalism's economic and social problems through political reform.[3]

History

Origins

This section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (September 2023) |

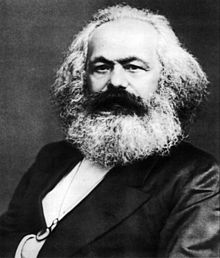

In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote:

The proletariat, the lowest stratum of our present society, cannot stir, cannot raise itself up, without the whole superincumbent strata of official society being sprung into the air. Though not in substance, yet in form, the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle. The proletariat of each country must, of course, first of all settle matters with its own bourgeoisie. In depicting the most general phases of the development of the proletariat, we traced the more or less veiled civil war, raging within existing society, up to the point where that war breaks out into open revolution, and where the violent overthrow of the bourgeoisie lays the foundation for the sway of the proletariat. The Communists fight for the attainment of the immediate aims, for the enforcement of the momentary interests of the working class; The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution.[4]

Twenty-four years after The Communist Manifesto, first published in 1848, Marx and Engels admitted that in developed countries, "labour may attain its goal by peaceful means".[5][6] Marxist scholar Adam Schaff argued that Marx, Engels, and Lenin had expressed such views "on many occasions".[7] By contrast, the Blanquist view emphasised the overthrow by force of the ruling elite in government by an active minority of revolutionaries, who then proceeded to implement socialist change, disregarding the state of readiness of society as a whole and the mass of the population in particular for revolutionary change.[citation needed]

In 1875, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) published a somewhat reformist Gotha Program, which Marx attacked in Critique of the Gotha Program, where he reiterated the need for the dictatorship of the proletariat. The reformist viewpoint was introduced into Marxist thought by Eduard Bernstein, one of the leaders of the SPD. From 1896 to 1898, Bernstein published a series of articles entitled "Probleme des Sozialismus" ("Problems of Socialism"). These articles led to a debate on revisionism in the SPD and can be seen as the origins of a reformist trend within Marxism.[citation needed]

In 1900, Rosa Luxemburg wrote Social Reform or Revolution?, a polemic against Bernstein's position. The work of reforms, Luxemburg argued, could only be carried on "in the framework of the social form created by the last revolution". In order to advance society to socialism from the capitalist 'social form', a social revolution will be necessary:

Bernstein, thundering against the conquest of political power as a theory of Blanquist violence, has the misfortune of labeling as a Blanquist error that which has always been the pivot and the motive force of human history. From the first appearance of class societies, having class struggle as the essential content of their history, the conquest of political power has been the aim of all rising classes. Here is the starting point and end of every historic period. In modern times, we see it in the struggle of the bourgeoisie against feudalism.[8][9]

In 1902, Vladimir Lenin attacked Bernstein's position in his What Is to Be Done? When Bernstein first put forward his ideas, the majority of the SPD rejected them. The 1899 congress of the SPD reaffirmed the Erfurt Program, as did the 1901 congress. The 1903 congress denounced "revisionist efforts".[citation needed]

World War I and Zimmerwald

On 4 August 1914, the SPD members of the Reichstag voted for the government's war budget, while the French and Belgian socialists publicly supported and joined their governments. The Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915, attended by Lenin and Leon Trotsky, saw the beginning of the end of the uneasy coexistence of revolutionary socialists and reformist socialists in the parties of the Second International. The conference adopted a proposal by Trotsky to avoid an immediate split with the Second International. Though initially opposed to it, Lenin voted[10] for Trotsky's resolution to avoid a split among anti-war socialists.

In December 1915 and March 1916, eighteen Social Democratic representatives, the Haase-Ledebour Group, voted against war credits and were expelled from the Social Democratic Party. Liebknecht wrote Revolutionary Socialism in Germany in 1916, arguing that this group was not a revolutionary socialist group despite their refusal to vote for war credits, further defining in his view what was meant by a revolutionary socialist.[11]

Russian Revolution and aftermath

| Part of a series on |

| Leninism |

|---|

|

Many revolutionary socialists argue that the Russian Revolution led by Vladimir Lenin follows the revolutionary socialist model of a revolutionary movement guided by a vanguard party. By contrast, the October Revolution is portrayed as a coup d'état or putsch along the lines of Blanquism.[citation needed]

Revolutionary socialists, particularly Trotskyists, argue that the Bolsheviks only seized power as the expression of the mass of workers and peasants, whose desires are brought into being by an organised force—the revolutionary party. Marxists such as Trotskyists argue that Lenin did not advocate seizing power until he felt that the majority of the population, represented in the soviets, demanded revolutionary change and no longer supported the reformist government of Alexander Kerensky established in the earlier revolution of February 1917. In the Lessons of October, Leon Trotsky wrote:

Lenin, after the experience of the reconnoiter, withdrew the slogan of the immediate overthrow of the Provisional Government. But he did not withdraw it for any set period of time, for so many weeks or months, but strictly in dependence upon how quickly the revolt of the masses against the conciliationists would grow.[12][non-primary source needed]

For these Marxists, the fact that the Bolsheviks won a majority (in alliance with the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries) in the second all-Russian congress of Soviets—democratically elected bodies—which convened at the time of the October revolution, shows that they had the popular support of the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, the vast majority of Russian society.[citation needed]

In his pamphlet Lessons of October, first published in 1924,[13][non-primary source needed] Trotsky argued that military power lay in the hands of the Bolsheviks before the October Revolution was carried out, but this power was not used against the government until the Bolsheviks gained mass support.[citation needed]

The mass of soldiers began to be led by the Bolshevik party after July 1917 and followed only the orders of the Military Revolutionary Committee under the leadership of Trotsky in October, also termed the Revolutionary Military Committee in Lenin's collected works.[14][non-primary source needed] Trotsky mobilized the Military Revolutionary Committee to seize power on the advent of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, which began on 25 October 1917.[citation needed]

The Communist International (also known as the Third International) was founded following the October Revolution. This International became widely identified with communism but also defined itself in terms of revolutionary socialism. However, in 1938 Trotskyists formed the Fourth International because they thought that the Third International turned to Marxism–Leninism—this latter International became identified with revolutionary socialism. Luxemburgism is another revolutionary socialist tradition.[citation needed]

Emerging from the Communist International but critical of the post-1924 Soviet Union, the Trotskyist tradition in Western Europe and elsewhere uses the term "revolutionary socialism". In 1932, the first issue of the first Canadian Trotskyist newspaper, The Vanguard, published an editorial entitled "Revolutionary Socialism vs Reformism".[15][non-primary source needed] Today, many Trotskyist groups advocate revolutionary socialism instead of reformism and consider themselves revolutionary socialists. The Committee for a Workers International states, "e campaign for new workers' parties and for them to adopt a socialist programme. At the same time, the CWI builds support for the ideas of revolutionary socialism".[16][non-primary source needed] In "The Case for Revolutionary Socialism", Alex Callinicos from the Socialist Workers Party in Britain argues in favour of it.[17][non-primary source needed]

Philosophy

Revolutionary socialist discourse has long debated the question of how the preordained revolution moment would originate, i.e., the extent to which revolt needs to be concertedly organized and by whom.[18] Rosa Luxemburg, in particular, was known for her theory of revolutionary spontaneity.[19][20] Critics argued that Luxemburg overstated the role of spontaneity and neglected the role of party organization.[21]

See also

References

- ^ Thompson, Carl D. (October 1903). "What Revolutionary Socialism Means". The Vanguard. Green Bay: Socialist Party of America. 2 (2): 13. Retrieved 31 August 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Kautsky, Karl (1903) . The Social Revolution. Translated by Simons, Algie Martin; Simons, May Wood. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Cox, Ronald W. (October 2019). "In Defense of Revolutionary Socialism: The Implications of Bhaskar Sunkara's 'The Socialist Manifesto'". Class, Race and Corporate Power. 7 (2). doi:10.25148/CRCP.7.2.008327. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich; Marx, Karl (1969) . The Communist Manifesto. "Chapter I. Bourgeois and Proletarians". Marx/Engels Collected Works. I. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 98–137. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Engels, Friedrich; Marx, Karl (187 September 1872). "La Liberté Speech". The Hague Congress of the International. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive. "e do not deny that there are countries like England and America, where labour may attain its goal by peaceful means."

- ^ Engels, Friedrich, Marx, Karl (1962). Karl Marx and Frederick Engels on Britain. Moscow: Foreign Languages Press.

- ^ Schaff, Adam (April–June 1973). "Marxist Theory on Revolution and Violence". Journal of the History of Ideas. University Press of Pennsylvania. 34 (2): 263–270. doi:10.2307/2708729. JSTOR 2708729. "Both Marx and Engels and, later, Lenin on many occasions referred to a peaceful revolution, that is, one attained by a class struggle, but not by violence."

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa (1986) . Social Reform or Revolution? "Chapter 8: Conquest of Political Power". London: Militant Publications. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Luxemburg, Rosa (1970). Rosa Luxemburg Speaks (2nd ed). Pathfinder. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0873481465.

- ^ Fagan, Guy (1980). Biographical Introduction to Christian Rakovsky, Selected Writings on Opposition in the USSR 1923–30 (1st ed.). London and New York: Allison & Busby and Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0850313796. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Liebknecht, Karl (1916). "Revolutionary Socialism in Germany". In Fraina, Louis C., ed. (1919). The Social Revolution in Germany. The Revolutionary Age Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1937) . Lessons of October. "Chapter Four: The April Conference". Translated by Wright, John. G. New York: Pioneer Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1937) . Lessons of October. Translated by Wright, John. G. New York: Pioneer Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon. Lessons of October. "Chapter Six: On the Eve of the October Revolution – the Aftermath". Translated by Wright, John. G. New York: Pioneer Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive. "On October 16th the Military Revolutionary Committee was created, the legal Soviet organ of insurrection."

- ^ "Revolutionary Socialism vs Reformism". The Vanguard (1). 1932. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Socialist History Project.

- ^ . Committee for a Workers International. Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 September 2007 – via the Socialist World.

- ^ Callinicos, Alex (7 December 2003). "The Case for Revolutionary Socialism". Socialist Workers Party. Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Gandio, Jason Del; Thompson, A. K. (2017-08-28). Spontaneous Combustion: The Eros Effect and Global Revolution. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-6727-6.

- ^ Talmon, Jacob L. (1991). Myth of the Nation and Vision of Revolution: Ideological Polarization in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 9781412848992.

- ^ Guérin, Daniel (2017). For a Libertarian Communism. PM Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-62963-236-0.

- ^ Nowak, Leszek; Paprzycki, Marcin (1993). Social System, Rationality and Revolution. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-5183-560-1.

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Wikipedia:Verifiability

Wikipedia:No original research#Primary, secondary and tertiary sources

Wikipedia:No original research#Primary, secondary and tertiary sources

Help:Maintenance template removal

Communist revolution

Category:Socialism

Socialism

Red flag (politics)

History of socialism

Outline of socialism

Age of Enlightenment

French Revolution

Revolutions of 1848

Socialist calculation debate

Socialist economics

Calculation in kind

Collective ownership

Cooperative

Common ownership

Critique of political economy

Economic democracy

Economic planning

Law of equal liberty#Equal liberty

Equal opportunity

Free association (Marxism and anarchism)

Left-wing market anarchism

Industrial democracy

Input–output model

Internationalism (politics)

Labor-time calculation

Labour voucher

Material balance planning

Social peer-to-peer processes#P2P economic system

Production for use

Sharing economy

Revolutionary spontaneity

Social dividend

Social ownership

Socialism in one country

Socialist mode of production

Soviet democracy

Strike action

To each according to his contribution

From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs

Vanguardism

Workers' self-management

Workplace democracy

Communalism (Bookchin)

Planned economy#Relationship with socialism

Planned economy#Decentralized planning

Inclusive Democracy

OGAS

Project Cybersyn

Soviet-type economic planning

Market socialism

Lange model

Mutualism (economic theory)

Socialist market economy

Socialist-oriented market economy

Participatory economics

Types of socialism

Socialism of the 21st century

African socialism

Arab socialism

Agrarian socialism

Anarchism

Authoritarian socialism

Blanquism

Buddhist socialism

Socialism with Chinese characteristics

Christian socialism

Communism

Democratic socialism

Democratic road to socialism

Cyber-utopianism

Ethical socialism

Eco-socialism

Evolutionary socialism

Socialist feminism

Fourierism

Free-market anarchism

Gandhian socialism

Guild socialism

Islamic socialism

Jewish left

Laissez-faire#Socialism

Liberal socialism

Libertarian socialism

Marhaenism

Market socialism

Marxism

Municipal socialism

Left-wing nationalism

Nkrumaism

Owenism

Popular socialism

Reformism

Religious socialism

Ricardian socialism

Henri de Saint-Simon#Ideas

Scientific socialism

Sewer socialism

Social democracy

State socialism

Syndicalism

Third World socialism

Utopian socialism

Yellow socialism

Labor Zionism

Gracchi

Mazdak

John Ball (priest)

Thomas More

Gerrard Winstanley

Étienne-Gabriel Morelly

Thomas Paine

Charles Hall (economist)

Sylvain Maréchal

Jacques Roux

Henri de Saint-Simon

François-Noël Babeuf

Philippe Buonarroti

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette

Jean-François Varlet

Louis Antoine de Saint-Just

Robert Owen

Charles Fourier

William Thompson (philosopher)

Thomas Hodgskin

Friedrich Wilhelm Schulz

Pierre Leroux

Constantin Pecqueur

Eugène Sue

Louis Auguste Blanqui

Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin

Théodore Dézamy

Victor Prosper Considerant

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Louis Blanc

Stephen Pearl Andrews

Alexander Herzen

Mikhail Bakunin

Karl Marx

Friedrich Engels

Alfred Russel Wallace

Pyotr Lavrov

Francesc Pi i Margall

Ferdinand Lassalle

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin

Nikolay Chernyshevsky

Leo Tolstoy

Louise Michel

William Morris

Mother Jones

Eugène Varlin

August Bebel

Anselmo Lorenzo

Sam Mainwaring

Peter Kropotkin

Edward Carpenter

Georges Sorel

Albert Parsons

Eduard Bernstein

Pablo Iglesias Posse

Lucy Parsons

Daniel De Leon

Errico Malatesta

Karl Kautsky

Oscar Wilde

Fred M. Taylor

Eugene V. Debs

Georgi Plekhanov

Francisco Ferrer

John Dewey

Enrico Barone

Émile Pouget

H. G. Wells

Constance Markievicz

W. E. B. Du Bois

Maxim Gorky

James Connolly

Emma Goldman

Mahatma Gandhi

Gustav Landauer

Alexander Berkman

Rosa Luxemburg

Karl Liebknecht

Léon Blum

Bertrand Russell

Antonie Pannekoek

Rudolf Rocker

James Larkin

Milly Witkop

Albert Einstein

Leon Trotsky

Helen Keller

R. H. Tawney

Pierre Monatte

Alexander Schapiro

Efim Yarchuk

Sylvia Pankhurst

Volin

Clement Attlee

Maria Spiridonova

Maria Nikiforova

Boris Kamkov

György Lukács

Ángel Pestaña

Karl Korsch

Karl Polanyi

Joan Peiró

Salvador Seguí

Sacco and Vanzetti

Nestor Makhno

Amadeo Bordiga

G. D. H. Cole

Yosif Gotman

Victor Serge

Aron Baron

Antonio Gramsci

Sacco and Vanzetti

Mark Mratchny

Stepan Petrichenko

Josip Broz Tito

Viktor Bilash

Fedir Shchus

Grigorii Maksimov

Sail Mohamed

Gaston Leval

Imre Nagy

Buenaventura Durruti

Antonio Soto (syndicalist)

Halyna Kuzmenko

Einar Gerhardsen

Diego Abad de Santillán

Niilo Wälläri

Dorothy Day

Herbert Marcuse

C. L. R. James

Juan García Oliver

Francisco Ascaso

Tage Erlander

Ida Mett

George Orwell

Paul Mattick

Daniel Guérin

Tommy Douglas

Federica Montseny

Jean-Paul Sartre

Léopold Sédar Senghor

Salvador Allende

Marinus van der Lubbe

Bruno Kreisky

François Mitterrand

Michel Chartrand

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Nelson Mandela

Murray Bookchin

Alexander Dubček

Howard Zinn

Cornelius Castoriadis

André Gorz

E. P. Thompson

Claude Lefort

Colin Ward

Michael Manley

Che Guevara

Noam Chomsky

Mikhail Gorbachev

Paul Avrich

Arthur Scargill

Takis Fotopoulos

Huey P. Newton

Richard D. Wolff

Tariq Ali

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva

John Holloway (sociologist)

Fred Hampton

Slavoj Žižek

Abdullah Öcalan

Jeremy Corbyn

Thomas Sankara

Cornel West

Hugo Chávez

Chris Hedges

Subcomandante Marcos

David Graeber

Yanis Varoufakis

Kohei Saito

Category:Socialist organizations

Category:International socialist organizations

Category:Socialist parties

Anarchism

Capitalism

Communist society

Criticism of capitalism

Criticism of socialism

Economic calculation problem

Economic system

French Left

Left-libertarianism

Libertarianism

List of socialist economists

Market abolitionism

Marxist philosophy

Nanosocialism

Progressivism

Socialism and LGBT rights

Socialist calculation debate

Socialist Party

Socialist state

Workers' council

Category:Socialism-related lists

Category:Socialism

Category:Socialism by country

Category:Socialists

List of socialist songs

File:Red flag II.svg

Updating...x

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.