A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Communist International | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Secretary | Georgi Dimitrov |

| Founders | |

| Founded | 2 March 1919 |

| Dissolved | 15 May 1943 |

| Preceded by | |

| Succeeded by | Cominform |

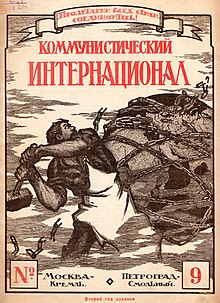

| Newspaper | Communist International |

| Youth wing | Young Communist International |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-left |

| Anthem | Kominternlied/Гимн Коминтерна |

| Part of a series on |

| Leninism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was an international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism, and which was led and controlled by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[3][4][5] The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress in 1920 to "struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the state".[6] The Comintern was preceded by the dissolution of the Second International in 1916. Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky were both honorary presidents of the Communist International.[7]

The Comintern held seven World Congresses in Moscow between 1919 and 1935. During that period, it also conducted thirteen Enlarged Plenums of its governing Executive Committee, which had much the same function as the somewhat larger and more grandiose Congresses. Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, dissolved the Comintern in 1943 to avoid antagonizing his allies in the later years of World War II, the United States and the United Kingdom. It was succeeded by the Cominform in 1947.

Organizational history

Failure of the Second International

Differences between the revolutionary and reformist wings of the workers' movement had been increasing for decades, but the outbreak of World War I was the catalyst for their separation. The Triple Alliance comprised two empires, while the Triple Entente was formed by three. Socialists had historically been anti-war and internationalist, fighting against what they perceived as militarist exploitation of the proletariat for bourgeois states. A majority of socialists voted in favor of resolutions for the Second International to call upon the international working class to resist war if it were declared.[8]

But after the beginning of World War I, many European socialist parties announced support for the war effort of their respective nations.[9] Including the British Labour Party who issued a manifesto stating, "the victory of the Germans would mean the death of democracy in Europe"[10] while making no such criticisms of the Russian Tsar. There were exceptions, such as the socialist parties of the Balkans[which?]. To Vladimir Lenin's surprise, even the Social Democratic Party of Germany voted in favor of war. After influential anti-war French Socialist Jean Jaurès was assassinated on 31 July 1914, the socialist parties hardened their support in France for their government of national unity.

Socialist parties in neutral countries mostly supported neutrality, rather than totally opposing the war. On the other hand, during the 1915 Zimmerwald Conference, Lenin, then a Swiss resident refugee, organized an opposition to the "imperialist war" as the Zimmerwald Left, publishing the pamphlet Socialism and War where he called socialists collaborating with their national governments social chauvinists, i.e. socialists in word, but nationalists in deed.[11]

The Second International divided into a revolutionary left-wing, a moderate center-wing, and a more reformist right-wing. Lenin condemned much of the center as "social pacifists" for several reasons, including their vote for war credits[clarification needed] despite publicly opposing the war. Lenin's term "social pacifist" aimed in particular at Ramsay MacDonald, leader of the Independent Labour Party in Britain, who opposed the war on grounds of pacifism but did not actively fight against it.

Discredited by its apathy towards world events, the Second International dissolved in 1916. In 1917, after the February Revolution overthrew the Romanov Dynasty, Lenin published the April Theses which openly supported revolutionary defeatism, where the Bolsheviks hoped that Russia would lose the war so that they could quickly cause a socialist insurrection.[12]

Impact of the Russian Revolution

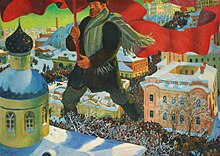

The victory of the Russian Communist Party in the Bolshevik Revolution of November 1917 was felt throughout the world and an alternative path to power to parliamentary politics was demonstrated. With much of Europe on the verge of economic and political collapse in the aftermath of the carnage of World War I, revolutionary sentiments were widespread. The Russian Bolsheviks headed by Lenin believed that unless socialist revolution swept Europe, they would be crushed by the military might of world capitalism just as the Paris Commune had been crushed by force of arms in 1871. The Bolsheviks believed that this required a new international to foment revolution in Europe and around the world.

First Period of the Comintern

During this early period (1919–1924), known as the First Period in Comintern history, with the Bolshevik Revolution under attack in the Russian Civil War and a wave of revolutions across Europe, the Comintern's priority was exporting the October Revolution. Some communist parties had secret military wings. One example is the M-Apparat of the Communist Party of Germany.

The Comintern was involved in the revolutions across Europe in this period, starting with the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. Several hundred agitators and financial aid were sent from the Soviet Union and Lenin was in regular contact with its leader Béla Kun. The next attempt was the March Action in Germany in 1921, including an attempt to dynamite the express train from Halle to Leipzig. After this failed, the Communist Party of Germany expelled its former chairman Paul Levi from the party for publicly criticising the March Action in a pamphlet,[13] which was ratified by the Executive Committee of the Communist International prior to the Third Congress.[14] A new attempt was made at the time of the Ruhr crisis in spring and then again in selected parts of Germany in the autumn of 1923. The Red Army was mobilized, ready to come to the aid of the planned insurrection. Resolute action by the German government cancelled the plans, except due to miscommunication in Hamburg, where 200–300 communists attacked police stations, but were quickly defeated. In 1924, there was a failed coup in Estonia by the Communist Party of Estonia.

Founding Congress

The Comintern was founded at a Congress held in Moscow on 2–6 March 1919.[15] It opened with a tribute to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, recently murdered by the Freikorps during the Spartacist Uprising,[16] against the backdrop of the Russian Civil War. There were 52 delegates present from 34 parties.[17] They decided to form an Executive Committee with representatives of the most important sections and that other parties joining the International would have their own representatives. The Congress decided that the executive committee would elect a five-member bureau to run the daily affairs of the International. However, such a bureau was not formed and Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Christian Rakovsky later delegated the task of managing the International to Grigory Zinoviev as the Chairman of the Executive. Zinoviev was assisted by Angelica Balabanoff, acting as the secretary of the International, Victor L. Kibaltchitch[note 1] and Vladmir Ossipovich Mazin.[19] Lenin, Trotsky, and Alexandra Kollontai presented material. The main topic of discussion was the difference between bourgeois democracy and the dictatorship of the proletariat.[20]

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

|

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. |