A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Proportion of Black Americans in each county of the fifty states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico as of the 2020 U.S. census | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 46,936,733 (2020)[1] 14.2% of the total U.S. population (2020)[1] 41,104,200 (2020) (one race)[1] 12.4% of the total U.S. population (2020)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Across the United States, especially in the South and urban areas | |

| Languages | |

| English (American English dialects, African-American English) Louisiana Creole French Gullah Creole English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Protestant (71%) including Historically Black Protestant (53%), Evangelical Protestant (14%), and Mainline Protestant (4%); significant[note 1] others include Catholic (5%), Jehovah's Witnesses (2%), Muslim (2%), and unaffiliated (18%)[2] |

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa.[3][4] The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of enslaved Africans who are from the United States.[5][6][7] While some Black immigrants or their children may also come to identify as African American, the majority of first generation immigrants do not, preferring to identify with their nation of origin.[8][9]

African Americans constitute the second largest racial group in the U.S. after White Americans, as well as the third largest ethnic group after Hispanic and Latino Americans.[10] Most African Americans are descendants of enslaved people within the boundaries of the present United States.[11][12] On average, African Americans are of West/Central African with some European descent; some also have Native American and other ancestry.[13]

According to U.S. Census Bureau data, African immigrants generally do not self-identify as African American. The overwhelming majority of African immigrants identify instead with their own respective ethnicities (~95%).[9] Immigrants from some Caribbean and Latin American nations and their descendants may or may not also self-identify with the term.[7]

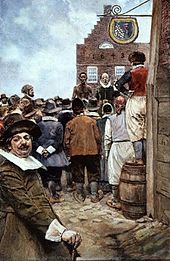

African American history began in the 16th century, with Africans from West Africa being sold to European slave traders and transported across the Atlantic to the Thirteen Colonies. After arriving in the Americas, they were sold as slaves to European colonists and put to work on plantations, particularly in the southern colonies. A few were able to achieve freedom through manumission or escape and founded independent communities before and during the American Revolution. After the United States was founded in 1783, most Black people continued to be enslaved, being most concentrated in the American South, with four million enslaved only liberated during and at the end of the Civil War in 1865.[14] During Reconstruction, they gained citizenship and the right to vote; due to the widespread policy and ideology of White supremacy, they were largely treated as second-class citizens and found themselves soon disenfranchised in the South. These circumstances changed due to participation in the military conflicts of the United States, substantial migration out of the South, the elimination of legal racial segregation, and the civil rights movement which sought political and social freedom. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first African American to be elected president of the United States.[15]

African American culture has a significant influence on worldwide culture, making numerous contributions to visual arts, literature, the English language, philosophy, politics, cuisine, sports and music. The African American contribution to popular music is so profound that virtually all American music, such as jazz, gospel, blues, disco, hip hop, R&B, soul and rock have their origins at least partially or entirely among African Americans.[16][17]

History

Colonial era

The vast majority of those who were enslaved and transported in the transatlantic slave trade were people from Central and West Africa, who had been captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids,[18] or sold by other West Africans, or by half-European "merchant princes"[19] to European slave traders, who brought them to the Americas.[20]

The first African slaves arrived via Santo Domingo to the San Miguel de Gualdape colony (most likely located in the Winyah Bay area of present-day South Carolina), founded by Spanish explorer Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón in 1526.[21] The ill-fated colony was almost immediately disrupted by a fight over leadership, during which the slaves revolted and fled the colony to seek refuge among local Native Americans. De Ayllón and many of the colonists died shortly afterward of an epidemic and the colony was abandoned. The settlers and the slaves who had not escaped returned to Haiti, whence they had come.[21]

The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free Black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a White Segovian conquistador in 1565 in St. Augustine (Spanish Florida), is the first known and recorded Christian marriage anywhere in what is now the continental United States.[22]

The first recorded Africans in English America (including most of the future United States) were "20 and odd negroes" who came to Jamestown, Virginia via Cape Comfort in August 1619 as indentured servants.[23] As many Virginian settlers began to die from harsh conditions, more and more Africans were brought to work as laborers.[24]

An indentured servant (who could be White or Black) would work for several years (usually four to seven) without wages. The status of indentured servants in early Virginia and Maryland was similar to slavery. Servants could be bought, sold, or leased and they could be physically beaten for disobedience or running away. Unlike slaves, they were freed after their term of service expired or was bought out, their children did not inherit their status, and on their release from contract they received "a year's provision of corn, double apparel, tools necessary", and a small cash payment called "freedom dues".[26] Africans could legally raise crops and cattle to purchase their freedom.[27] They raised families, married other Africans and sometimes intermarried with Native Americans or European settlers.[28]

By the 1640s and 1650s, several African families owned farms around Jamestown and some became wealthy by colonial standards and purchased indentured servants of their own. In 1640, the Virginia General Court recorded the earliest documentation of lifetime slavery when they sentenced John Punch, a Negro, to lifetime servitude under his master Hugh Gwyn for running away.[29][30]

In the Spanish Florida some Spanish married or had unions with Pensacola, Creek or African women, both slave and free, and their descendants created a mixed-race population of mestizos and mulattos. The Spanish encouraged slaves from the colony of Georgia to come to Florida as a refuge, promising freedom in exchange for conversion to Catholicism. King Charles II issued a royal proclamation freeing all slaves who fled to Spanish Florida and accepted conversion and baptism. Most went to the area around St. Augustine, but escaped slaves also reached Pensacola. St. Augustine had mustered an all-Black militia unit defending Spanish Florida as early as 1683.[31]

One of the Dutch African arrivals, Anthony Johnson, would later own one of the first Black "slaves", John Casor, resulting from the court ruling of a civil case.[32][33]

The popular conception of a race-based slave system did not fully develop until the 18th century. The Dutch West India Company introduced slavery in 1625 with the importation of eleven Black slaves into New Amsterdam (present-day New York City). All the colony's slaves, however, were freed upon its surrender to the English.[34]

Massachusetts was the first English colony to legally recognize slavery in 1641. In 1662, Virginia passed a law that children of enslaved women took the status of the mother, rather than that of the father, as under common law. This legal principle was called partus sequitur ventrum.[35][36]

By an act of 1699, the colony ordered all free Blacks deported, virtually defining as slaves all people of African descent who remained in the colony.[37] In 1670, the colonial assembly passed a law prohibiting free and baptized Blacks (and Indians) from purchasing Christians (in this act meaning White Europeans) but allowing them to buy people "of their owne nation".[38]

In the Spanish Louisiana although there was no movement toward abolition of the African slave trade, Spanish rule introduced a new law called coartación, which allowed slaves to buy their freedom, and that of others.[41] Although some did not have the money to buy their freedom, government measures on slavery allowed many free Blacks. That brought problems to the Spaniards with the French Creoles who also populated Spanish Louisiana, French creoles cited that measure as one of the system's worst elements.[42]

First established in South Carolina in 1704, groups of armed White men—slave patrols—were formed to monitor enslaved Black people.[43] Their function was to police slaves, especially fugitives. Slave owners feared that slaves might organize revolts or slave rebellions, so state militias were formed in order to provide a military command structure and discipline within the slave patrols so they could be used to detect, encounter, and crush any organized slave meetings which might lead to revolts or rebellions.[43]

The earliest African American congregations and churches were organized before 1800 in both northern and southern cities following the Great Awakening. By 1775, Africans made up 20% of the population in the American colonies, which made them the second largest ethnic group after English Americans.[44]

From the American Revolution to the Civil War

During the 1770s, Africans, both enslaved and free, helped rebellious American colonists secure their independence by defeating the British in the American Revolutionary War.[45] Blacks played a role in both sides in the American Revolution. Activists in the Patriot cause included James Armistead, Prince Whipple, and Oliver Cromwell.[46][47] Around 15,000 Black Loyalists left with the British after the war, most of them ending up as free Black people in England[48] or its colonies, such as the Black Nova Scotians and the Sierra Leone Creole people.[49][50]

In the Spanish Louisiana, Governor Bernardo de Gálvez organized Spanish free Black men into two militia companies to defend New Orleans during the American Revolution. They fought in the 1779 battle in which Spain captured Baton Rouge from the British. Gálvez also commanded them in campaigns against the British outposts in Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida. He recruited slaves for the militia by pledging to free anyone who was seriously wounded and promised to secure a low price for coartación (buy their freedom and that of others) for those who received lesser wounds. During the 1790s, Governor Francisco Luis Héctor, baron of Carondelet reinforced local fortifications and recruit even more free Black men for the militia. Carondelet doubled the number of free Black men who served, creating two more militia companies—one made up of Black members and the other of pardo (mixed race). Serving in the militia brought free Black men one step closer to equality with Whites, allowing them, for example, the right to carry arms and boosting their earning power. However, actually these privileges distanced free Black men from enslaved Blacks and encouraged them to identify with Whites.[42]

Slavery had been tacitly enshrined in the U.S. Constitution through provisions such as Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, commonly known as the 3/5 compromise. Because of Section 9, Clause 1, Congress was unable to pass an Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves until 1807.[51] Fugitive slave laws (derived from the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution—Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3) were passed by Congress in 1793 and 1850, guaranteeing the right for a slaveholder to recover an escaped slave within the U.S.[40] Slave owners, who viewed slaves as property, made it a federal crime to assist those who had escaped slavery or to interfere with their capture.[39] Slavery, which by then meant almost exclusively Black people, was the most important political issue in the Antebellum United States, leading to one crisis after another. Among these were the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Dred Scott decision, and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry.

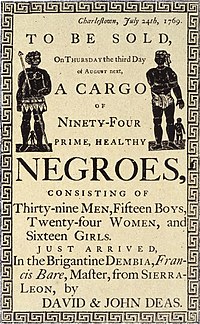

Prior to the Civil War, eight serving presidents owned slaves, a practice protected by the U.S. Constitution.[52] By 1860, there were 3.5 to 4.4 million enslaved Black people in the U.S. due to the Atlantic slave trade, and another 488,000–500,000 Blacks lived free (with legislated limits)[53] across the country.[54] With legislated limits imposed upon them in addition to "unconquerable prejudice" from Whites according to Henry Clay,[55] some Black people who were not enslaved left the U.S. for Liberia in West Africa.[53] Liberia began as a settlement of the American Colonization Society (ACS) in 1821, with the abolitionist members of the ACS believing Blacks would face better chances for freedom and equality in Africa.[53]

The slaves not only constituted a large investment, they produced America's most valuable product and export: cotton. They not only helped build the U.S. Capitol, they built the White House and other District of Columbia buildings. (See Slavery in the District of Columbia.[56]) Similar building projects existed in the slave states.

By 1815, the domestic slave trade had become a major economic activity in the United States; it lasted until the 1860s.[57] Historians estimate nearly one million in total took part in the forced migration of this new "Middle Passage." The historian Ira Berlin called this forced migration of slaves the "central event" in the life of a slave between the American Revolution and the Civil War, writing that whether slaves were directly uprooted or lived in fear that they or their families would be involuntarily moved, "the massive deportation traumatized black people."[58] Individuals lost their connection to families and clans, and many ethnic Africans lost their knowledge of varying tribal origins in Africa.[57]

The 1863 photograph of Wilson Chinn, a branded slave from Louisiana, like the one of Gordon and his scarred back, served as two early examples of how the newborn medium of photography could encapsulate the cruelty of slavery.[59]

Emigration of free Blacks to their continent of origin had been proposed since the Revolutionary war. After Haiti became independent, it tried to recruit African Americans to migrate there after it re-established trade relations with the United States. The Haitian Union was a group formed to promote relations between the countries.[60] After riots against Blacks in Cincinnati, its Black community sponsored founding of the Wilberforce Colony, an initially successful settlement of African American immigrants to Canada. The colony was one of the first such independent political entities. It lasted for a number of decades and provided a destination for about 200 Black families emigrating from a number of locations in the United States.[60]

In 1863, during the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. The proclamation declared that all slaves in Confederate-held territory were free.[61] Advancing Union troops enforced the proclamation, with Texas being the last state to be emancipated, in 1865.[62]

Slavery in Union-held Confederate territory continued, at least on paper, until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.[63] While the Naturalization Act of 1790 limited U.S. citizenship to Whites only,[64][65] the 14th Amendment (1868) gave Black people citizenship, and the 15th Amendment (1870) gave Black males the right to vote (which would still be denied to all women until 1920).[66]

Reconstruction era and Jim Crow

African Americans quickly set up congregations for themselves, as well as schools and community/civic associations, to have space away from White control or oversight. While the post-war Reconstruction era was initially a time of progress for African Americans, that period ended in 1876. By the late 1890s, Southern states enacted Jim Crow laws to enforce racial segregation and disenfranchisement.[67] Segregation, which began with slavery, continued with Jim Crow laws, with signs used to show Blacks where they could legally walk, talk, drink, rest, or eat.[68] For those places that were racially mixed, non-Whites had to wait until all White customers were dealt with.[68] Most African Americans obeyed the Jim Crow laws, to avoid racially motivated violence. To maintain self-esteem and dignity, African Americans such as Anthony Overton and Mary McLeod Bethune continued to build their own schools, churches, banks, social clubs, and other businesses.[69]

In the last decade of the 19th century, racially discriminatory laws and racial violence aimed at African Americans began to mushroom in the United States, a period often referred to as the "nadir of American race relations". These discriminatory acts included racial segregation—upheld by the United States Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896—which was legally mandated by southern states and nationwide at the local level of government, voter suppression or disenfranchisement in the southern states, denial of economic opportunity or resources nationwide, and private acts of violence and mass racial violence aimed at African Americans unhindered or encouraged by government authorities.[70]

Great migration and civil rights movement

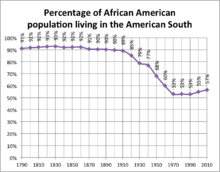

The desperate conditions of African Americans in the South sparked the Great Migration during the first half of the 20th century which led to a growing African American community in Northern and Western United States.[72] The rapid influx of Blacks disturbed the racial balance within Northern and Western cities, exacerbating hostility between both Blacks and Whites in the two regions.[73] The Red Summer of 1919 was marked by hundreds of deaths and higher casualties across the U.S. as a result of race riots that occurred in more than three dozen cities, such as the Chicago race riot of 1919 and the Omaha race riot of 1919. Overall, Blacks in Northern and Western cities experienced systemic discrimination in a plethora of aspects of life. Within employment, economic opportunities for Blacks were routed to the lowest-status and restrictive in potential mobility. At the 1900 Hampton Negro Conference, Reverend Matthew Anderson said: "...the lines along most of the avenues of wage earning are more rigidly drawn in the North than in the South."[74] Within the housing market, stronger discriminatory measures were used in correlation to the influx, resulting in a mix of "targeted violence, restrictive covenants, redlining and racial steering".[75] While many Whites defended their space with violence, intimidation, or legal tactics toward African Americans, many other Whites migrated to more racially homogeneous suburban or exurban regions, a process known as White flight.[76]

Despite discrimination, drawing cards for leaving the hopelessness in the South were the growth of African American institutions and communities in Northern cities. Institutions included Black oriented organizations (e.g., Urban League, NAACP), churches, businesses, and newspapers, as well as successes in the development in African American intellectual culture, music, and popular culture (e.g., Harlem Renaissance, Chicago Black Renaissance). The Cotton Club in Harlem was a Whites-only establishment, with Blacks (such as Duke Ellington) allowed to perform, but to a White audience.[77] Black Americans also found a new ground for political power in Northern cities, without the enforced disabilities of Jim Crow.[78][79]

By the 1950s, the civil rights movement was gaining momentum. A 1955 lynching that sparked public outrage about injustice was that of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago. Spending the summer with relatives in Money, Mississippi, Till was killed for allegedly having wolf-whistled at a White woman. Till had been badly beaten, one of his eyes was gouged out, and he was shot in the head. The visceral response to his mother's decision to have an open-casket funeral mobilized the Black community throughout the U.S.[80] Vann R. Newkirk| wrote "the trial of his killers became a pageant illuminating the tyranny of White supremacy".[80] The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted by an all-White jury.[81] One hundred days after Emmett Till's murder, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus in Alabama—indeed, Parks told Emmett's mother Mamie Till that "the photograph of Emmett's disfigured face in the casket was set in her mind when she refused to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus."[82]

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the conditions which brought it into being are credited with putting pressure on presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Johnson put his support behind passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that banned discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and labor unions, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which expanded federal authority over states to ensure Black political participation through protection of voter registration and elections.[83] By 1966, the emergence of the Black Power movement, which lasted from 1966 to 1975, expanded upon the aims of the civil rights movement to include economic and political self-sufficiency, and freedom from White authority.[84]

During the post-war period, many African Americans continued to be economically disadvantaged relative to other Americans. Average Black income stood at 54 percent of that of White workers in 1947, and 55 percent in 1962. In 1959, median family income for Whites was $5,600, compared with $2,900 for non-White families. In 1965, 43 percent of all Black families fell into the poverty bracket, earning under $3,000 a year. The Sixties saw improvements in the social and economic conditions of many Black Americans.[85]

From 1965 to 1969, Black family income rose from 54 to 60 percent of White family income. In 1968, 23 percent of Black families earned under $3,000 a year, compared with 41 percent in 1960. In 1965, 19 percent of Black Americans had incomes equal to the national median, a proportion that rose to 27 percent by 1967. In 1960, the median level of education for Blacks had been 10.8 years, and by the late Sixties the figure rose to 12.2 years, half a year behind the median for Whites.[85]

Post–civil rights era

Politically and economically, African Americans have made substantial strides during the post–civil rights era. In 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the first African American Supreme Court Justice. In 1968, Shirley Chisholm became the first Black woman elected to the U.S. Congress. In 1989, Douglas Wilder became the first African American elected governor in U.S. history. Clarence Thomas succeeded Marshall to become the second African American Supreme Court Justice in 1991. In 1992, Carol Moseley-Braun of Illinois became the first African American woman elected to the U.S. Senate. There were 8,936 Black officeholders in the United States in 2000, showing a net increase of 7,467 since 1970. In 2001, there were 484 Black mayors.[86]

In 2005, the number of Africans immigrating to the United States, in a single year, surpassed the peak number who were involuntarily brought to the United States during the Atlantic Slave Trade.[87] On November 4, 2008, Democratic Senator Barack Obama defeated Republican Senator John McCain to become the first African American to be elected president. At least 95 percent of African American voters voted for Obama.[88][89] He also received overwhelming support from young and educated Whites, a majority of Asians,[90] and Hispanics,[90] picking up a number of new states in the Democratic electoral column.[88][89] Obama lost the overall White vote, although he won a larger proportion of White votes than any previous nonincumbent Democratic presidential candidate since Jimmy Carter.[91] Obama was reelected for a second and final term, by a similar margin on November 6, 2012.[92] In 2021, Kamala Harris became the first woman, the first African American, and the first Asian American to serve as Vice President of the United States.[93]

Demographics

In 1790, when the first U.S. Census was taken, Africans (including slaves and free people) numbered about 760,000—about 19.3% of the population. In 1860, at the start of the Civil War, the African American population had increased to 4.4 million, but the percentage rate dropped to 14% of the overall population of the country. The vast majority were slaves, with only 488,000 counted as "freemen". By 1900, the Black population had doubled and reached 8.8 million.[94]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=African-Americans

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.