A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Its current readable prose size is 106 kilobytes. (June 2022) |

Paul[a] (previously called Saul of Tarsus;[b] c. 5 – c. 64/65 AD), commonly known as Paul the Apostle[7] and Saint Paul,[8] was a Christian apostle and missionary who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world.[9] Generally regarded as one of the most important figures of the Apostolic Age,[8][10] he founded several Christian communities in Asia Minor and Europe from the mid-40s to the mid-50s AD.[11]

According to the New Testament book Acts of the Apostles, Paul lived as a Pharisee.[12] He participated in the persecution of early disciples of Jesus, possibly Hellenised diaspora Jews converted to Christianity,[13] in the area of Jerusalem, prior to his conversion.[note 1] Some time after having approved of the execution of Stephen,[14] Paul was traveling on the road to Damascus so that he might find any Christians there and bring them "bound to Jerusalem" (ESV).[15] At midday, a light brighter than the sun shone around both him and those with him, causing all to fall to the ground, with the risen Christ verbally addressing Paul regarding his persecution.[16][17] Having been made blind,[18] along with being commanded to enter the city, his sight was restored three days later by Ananias of Damascus. After these events, Paul was baptized, beginning immediately to proclaim that Jesus of Nazareth was the Jewish messiah and the Son of God.[19] Approximately half of the content in the book of Acts details the life and works of Paul.

Fourteen of the 27 books in the New Testament have traditionally been attributed to Paul.[20] Seven of the Pauline epistles are undisputed by scholars as being authentic, with varying degrees of argument about the remainder. Pauline authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews is not asserted in the Epistle itself and was already doubted in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.[note 2] It was almost unquestioningly accepted from the 5th to the 16th centuries that Paul was the author of Hebrews,[22] but that view is now almost universally rejected by scholars.[22][23] The other six are believed by some scholars to have come from followers writing in his name, using material from Paul's surviving letters and letters written by him that no longer survive.[9][8][note 3] Other scholars argue that the idea of a pseudonymous author for the disputed epistles raises many problems.[25]

Today, Paul's epistles continue to be vital roots of the theology, worship and pastoral life in the Latin and Protestant traditions of the West, as well as the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox traditions of the East.[26] Paul's influence on Christian thought and practice has been characterized as being as "profound as it is pervasive", among that of many other apostles and missionaries involved in the spread of the Christian faith.[9]

Names

Paul's Jewish name was "Saul" (Hebrew: שָׁאוּל, Modern: Sha'ûl, Tiberian: Šā'ûl), perhaps after the biblical King Saul, the first king of Israel and like Paul a member of the Tribe of Benjamin; the Latin name Paul, meaning small, was not a result of his conversion as it is commonly believed but a second name for use in communicating with a Greco-Roman audience.[27][28]

According to the Acts of the Apostles, he was a Roman citizen.[29] As such, he bore the Latin name "Paul" – in Latin Paulus and in biblical Greek Παῦλος (Paulos).[30][31] It was typical for the Jews of that time to have two names: one Hebrew, the other Latin or Greek.[32][33][34]

Jesus called him "Saul, Saul"[35] in "the Hebrew tongue" in the Acts of the Apostles, when he had the vision which led to his conversion on the road to Damascus.[36] Later, in a vision to Ananias of Damascus, "the Lord" referred to him as "Saul, of Tarsus".[37] When Ananias came to restore his sight, he called him "Brother Saul".[38]

In Acts 13:9, Saul is called "Paul" for the first time on the island of Cyprus – much later than the time of his conversion.[39] The author of Luke–Acts indicates that the names were interchangeable: "Saul, who also is called Paul." He refers to him as Paul through the remainder of Acts. This was apparently Paul's preference since he is called Paul in all other Bible books where he is mentioned, including those that he authored. Adopting his Roman name was typical of Paul's missionary style. His method was to put people at their ease and to approach them with his message in a language and style to which they could relate, as in 1 Corinthians 9:19–23.[40][41][42]

Sources

Information about Paul is derived mainly from the Acts of the Apostles and Pauline epistles.[43] The authenticity of Acts of the Apostles is sometimes questioned since it contradicts Paul's epistles on multiple accounts, in particular concerning the frequency of Paul's visits to the church in Jerusalem.[44] Sources outside the New Testament include the First Epistle of Clement attributed to Clement of Rome (died 99). Paul has scant mention in Ignatius of Antioch's epistles the Romans and to the Ephesians, dating to the early 2nd-century.[45] He is mentioned in Polycarp's epistle to the Philippians, dating to the first half of the 2nd century. The Historia Ecclesiae ('Church History') by Eusebius (died 339) contains a few pages on Paul's life. The apocryphal Acts narrating the life of Paul (Acts of Paul, Acts of Paul and Thecla, Acts of Peter and Paul), the apocryphal epistles attributed to him (the Latin Epistle to the Laodiceans, the Third Epistle to the Corinthians, and the Correspondence of Paul and Seneca) and some apocalyptic texts attributed to him (Apocalypse of Paul and Coptic Apocalypse of Paul). These writings are all late, dating from the 2nd to the 4th century.

Biography

Early life

The two main sources of information that give access to the earliest segments of Paul's career are the Acts of the Apostles and the autobiographical elements of Paul's letters to the early Christian communities.[43] The Pauline epistles contain little information about Paul's pre-conversion past.[46] Paul was likely born between the years of 5 BC and 5 AD.[47] The Acts of the Apostles indicates that Paul was a Roman citizen by birth, but Helmut Koester takes issue with the evidence presented by the text.[48][49]

He was from a devout Jewish family[50] based in the city of Tarsus.[27] One of the larger centers of trade on the Mediterranean coast and renowned for its university, Tarsus had been among the most influential cities in Asia Minor since the time of Alexander the Great, who died in 323 BC.[50]

Paul referred to himself as being "of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of the Hebrews; as touching the law, a Pharisee".[51][52] The Bible reveals very little about Paul's family. Acts quotes Paul referring to his family by saying he was "a Pharisee, born of Pharisees".[53][54] Paul's nephew, his sister's son, is mentioned in Acts 23:16.[55] In Romans 16:7, he states that his relatives, Andronicus and Junia, were Christians before he was and were prominent among the Apostles.[56]

The family had a history of religious piety.[57][note 4] Apparently, the family lineage had been very attached to Pharisaic traditions and observances for generations.[58] Acts says that he was an artisan involved in the leather crafting or tent-making profession.[59][60] This was to become an initial connection with Priscilla and Aquila, with whom he would partner in tentmaking[61] and later become very important teammates as fellow missionaries.[62]

While he was still fairly young, he was sent to Jerusalem to receive his education at the school of Gamaliel,[63][52] one of the most noted teachers of Jewish law in history. Although modern scholarship agrees that Paul was educated under the supervision of Gamaliel in Jerusalem,[52] he was not preparing to become a scholar of Jewish law, and probably never had any contact with the Hillelite school.[52] Some of his family may have resided in Jerusalem since later the son of one of his sisters saved his life there.[64][27] Nothing more is known of his biography until he takes an active part in the martyrdom of Stephen,[65] a Hellenised diaspora Jew.[66]

Although it is known (from his biography and from Acts) that Paul could and did speak Aramaic (then known as "Hebrew"),[27] modern scholarship suggests that Koine Greek was his first language.[67] In his letters, Paul drew heavily on his knowledge of Stoic philosophy, using Stoic terms and metaphors to assist his new Gentile converts in their understanding of the Gospel and to explain his Christology.[68][69]

Persecutor of early Christians

Paul says that prior to his conversion,[70] he persecuted early Christians "beyond measure", more specifically Hellenised diaspora Jewish members who had returned to the area of Jerusalem.[71][note 1] According to James Dunn, the Jerusalem community consisted of "Hebrews", Jews speaking both Aramaic and Greek, and "Hellenists", Jews speaking only Greek, possibly diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem.[73] Paul's initial persecution of Christians probably was directed against these Greek-speaking "Hellenists" due to their anti-Temple attitude.[74] Within the early Jewish Christian community, this also set them apart from the "Hebrews" and their continuing participation in the Temple cult.[74]

Conversion

Paul's conversion can be dated to 31–36 AD[75][76][77] by his reference to it in one of his letters. In Galatians 1:16, Paul writes that God "was pleased to reveal his son to me."[78] In 1 Corinthians 15:8, as he lists the order in which Jesus appeared to his disciples after his resurrection, Paul writes, "last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also."[79]

According to the account in the Acts of the Apostles, it took place on the road to Damascus, where he reported having experienced a vision of the ascended Jesus. The account says that "He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, 'Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?' He asked, 'Who are you, Lord?' The reply came, 'I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting'."[80]

According to the account in Acts 9:1–22, he was blinded for three days and had to be led into Damascus by the hand.[81] During these three days, Saul took no food or water and spent his time in prayer to God. When Ananias of Damascus arrived, he laid his hands on him and said: "Brother Saul, the Lord, Jesus, that appeared unto thee in the way as thou camest, hath sent me, that thou mightest receive thy sight, and be filled with the Holy Ghost."[82] His sight was restored, he got up and was baptized.[83] This story occurs only in Acts, not in the Pauline epistles.[84]

The author of the Acts of the Apostles may have learned of Paul's conversion from the church in Jerusalem, or from the church in Antioch, or possibly from Paul himself.[85]

According to Timo Eskola, early Christian theology and discourse was influenced by the Jewish Merkabah tradition.[86] Similarly, Alan Segal and Daniel Boyarin regard Paul's accounts of his conversion experience and his ascent to the heavens (in 2 Corinthians 12) as the earliest first-person accounts that are extant of a Merkabah mystic in Jewish or Christian literature. Conversely, Timothy Churchill has argued that Paul's Damascus road encounter does not fit the pattern of Merkabah.[87]

Post-conversion

According to Acts:

And immediately he proclaimed Jesus in the synagogues, saying, "He is the Son of God." And all who heard him were amazed and said, "Is not this the man who made havoc in Jerusalem of those who called upon this name? And has he not come here for this purpose, to bring them bound before the chief priests?" But Saul increased all the more in strength, and confounded the Jews who lived in Damascus by proving that Jesus was the Christ.

— Acts 9:20–22[88]

Early ministry

After his conversion, Paul went to Damascus, where Acts 9 states he was healed of his blindness and baptized by Ananias of Damascus.[89] Paul says that it was in Damascus that he barely escaped death.[90] Paul also says that he then went first to Arabia, and then came back to Damascus.[91][92] Paul's trip to Arabia is not mentioned anywhere else in the Bible, and some suppose he actually traveled to Mount Sinai for meditations in the desert.[93][94] He describes in Galatians how three years after his conversion he went to Jerusalem. There he met James and stayed with Simon Peter for 15 days.[95] Paul located Mount Sinai in Arabia in Galatians 4:24–25.[96]

Paul asserted that he received the Gospel not from man, but directly by "the revelation of Jesus Christ".[97] He claimed almost total independence from the Jerusalem community[98] (possibly in the Cenacle), but agreed with it on the nature and content of the gospel.[99] He appeared eager to bring material support to Jerusalem from the various growing Gentile churches that he started. In his writings, Paul used the persecutions he endured to avow proximity and union with Jesus and as a validation of his teaching.

Paul's narrative in Galatians states that 14 years after his conversion he went again to Jerusalem.[100] It is not known what happened during this time, but both Acts and Galatians provide some details.[101] Though a view is held that Paul spent 14 years studying the scriptures and growing in the faith. At the end of this time, Barnabas went to find Paul and brought him to Antioch.[102][103] The Christian community at Antioch had been established by Hellenised diaspora Jews living in Jerusalem, who played an important role in reaching a Gentile, Greek audience, notably at Antioch, which had a large Jewish community and significant numbers of Gentile "God-fearers."[104] From Antioch the mission to the Gentiles started, which would fundamentally change the character of the early Christian movement, eventually turning it into a new, Gentile religion.[105]

When a famine occurred in Judea, around 45–46,[106] Paul and Barnabas journeyed to Jerusalem to deliver financial support from the Antioch community.[107] According to Acts, Antioch had become an alternative center for Christians following the dispersion of the believers after the death of Stephen. It was in Antioch that the followers of Jesus were first called "Christians".[108]

First missionary journey

The author of Acts arranges Paul's travels into three separate journeys. The first journey,[109] for which Paul and Barnabas were commissioned by the Antioch community,[110] and led initially by Barnabas,[note 5] took Barnabas and Paul from Antioch to Cyprus then into southern Asia Minor, and finally returning to Antioch. In Cyprus, Paul rebukes and blinds Elymas the magician[111] who was criticizing their teachings.

They sailed to Perga in Pamphylia. John Mark left them and returned to Jerusalem. Paul and Barnabas went on to Pisidian Antioch. On Sabbath they went to the synagogue. The leaders invited them to speak. Paul reviewed Israelite history from life in Egypt to King David. He introduced Jesus as a descendant of David brought to Israel by God. He said that his team came to town to bring the message of salvation. He recounted the story of Jesus' death and resurrection. He quoted from the Septuagint[112] to assert that Jesus was the promised Christos who brought them forgiveness for their sins. Both the Jews and the "God-fearing" Gentiles invited them to talk more next Sabbath. At that time almost the whole city gathered. This upset some influential Jews who spoke against them. Paul used the occasion to announce a change in his mission which from then on would be to the Gentiles.[113]

Antioch served as a major Christian home base for Paul's early missionary activities,[4] and he remained there for "a long time with the disciples"[114] at the conclusion of his first journey. The exact duration of Paul's stay in Antioch is unknown, with estimates ranging from nine months to as long as eight years.[115]

In Raymond Brown's An Introduction to the New Testament (1997), a chronology of events in Paul's life is presented, illustrated from later 20th-century writings of biblical scholars.[116] The first missionary journey of Paul is assigned a "traditional" (and majority) dating of 46–49 AD, compared to a "revisionist" (and minority) dating of after 37 AD.[117]

Council of Jerusalem

A vital meeting between Paul and the Jerusalem church took place in the year 49 AD by "traditional" (and majority) dating, compared to a "revisionist" (and minority) dating of 47/51 AD.[118] The meeting is described in Acts 15:2[119] and usually seen as the same event mentioned by Paul in Galatians 2:1.[120][46] The key question raised was whether Gentile converts needed to be circumcised.[121][122] At this meeting, Paul states in his letter to the Galatians, Peter, James, and John accepted Paul's mission to the Gentiles.

The Jerusalem meetings are mentioned in Acts, and also in Paul's letters.[123] For example, the Jerusalem visit for famine relief[124] apparently corresponds to the "first visit" (to Peter and James only).[125][123] F. F. Bruce suggested that the "fourteen years" could be from Paul's conversion rather than from his first visit to Jerusalem.[126]

Incident at Antioch

Despite the agreement achieved at the Council of Jerusalem, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter in a dispute sometimes called the "Incident at Antioch", over Peter's reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians in Antioch because they did not strictly adhere to Jewish customs.[121]

Writing later of the incident, Paul recounts, "I opposed to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong", and says he told Peter, "You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?"[127] Paul also mentions that even Barnabas, his traveling companion and fellow apostle until that time, sided with Peter.[121]

The outcome of the incident remains uncertain. The Catholic Encyclopedia suggests that Paul won the argument, because "Paul's account of the incident leaves no doubt that Peter saw the justice of the rebuke".[121] However, Paul himself never mentions a victory, and L. Michael White's From Jesus to Christianity draws the opposite conclusion: "The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as persona non grata, never again to return".[128]

The primary source account of the Incident at Antioch is Paul's letter to the Galatians.[127]

Second missionary journey

Paul left for his second missionary journey from Jerusalem, in late Autumn 49 AD,[131] after the meeting of the Council of Jerusalem where the circumcision question was debated. On their trip around the Mediterranean Sea, Paul and his companion Barnabas stopped in Antioch where they had a sharp argument about taking John Mark with them on their trips. The Acts of the Apostles said that John Mark had left them in a previous trip and gone home. Unable to resolve the dispute, Paul and Barnabas decided to separate; Barnabas took John Mark with him, while Silas joined Paul.

Paul and Silas initially visited Tarsus (Paul's birthplace), Derbe and Lystra. In Lystra, they met Timothy, a disciple who was spoken well of, and decided to take him with them. Paul and his companions, Silas and Timothy, had plans to journey to the southwest portion of Asia Minor to preach the gospel but during the night, Paul had a vision of a man of Macedonia standing and begging him to go to Macedonia to help them. After seeing the vision, Paul and his companions left for Macedonia to preach the gospel to them.[132] The Church kept growing, adding believers, and strengthening in faith daily.[133]

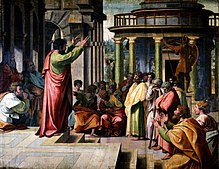

In Philippi, Paul cast a spirit of divination out of a servant girl, whose masters were then unhappy about the loss of income her soothsaying provided.[134] They seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace before the authorities and Paul and Silas were put in jail. After a miraculous earthquake, the gates of the prison fell apart and Paul and Silas could have escaped but remained; this event led to the conversion of the jailor.[135] They continued traveling, going by Berea and then to Athens, where Paul preached to the Jews and God-fearing Greeks in the synagogue and to the Greek intellectuals in the Areopagus. Paul continued from Athens to Corinth.

Interval in Corinth

Around 50–52 AD, Paul spent 18 months in Corinth. The reference in Acts to Proconsul Gallio helps ascertain this date (cf. Gallio Inscription).[46] In Corinth, Paul met Priscilla and Aquila,[136] who became faithful believers and helped Paul through his other missionary journeys. The couple followed Paul and his companions to Ephesus, and stayed there to start one of the strongest and most faithful churches at that time.[137]

In 52, departing from Corinth, Paul stopped at the nearby village of Cenchreae to have his hair cut off, because of a vow he had earlier taken.[138] It is possible this was to be a final haircut prior to fulfilling his vow to become a Nazirite for a defined period of time.[139] With Priscilla and Aquila, the missionaries then sailed to Ephesus[140] and then Paul alone went on to Caesarea to greet the Church there. He then traveled north to Antioch, where he stayed for some time (Ancient Greek: ποιησας χρονον, "perhaps about a year"), before leaving again on a third missionary journey.[citation needed] Some New Testament texts[note 6] suggest that he also visited Jerusalem during this period for one of the Jewish feasts, possibly Pentecost.[141] Textual critic Henry Alford and others consider the reference to a Jerusalem visit to be genuine[142] and it accords with Acts 21:29,[143] according to which Paul and Trophimus the Ephesian had previously been seen in Jerusalem.

Third missionary journey

According to Acts, Paul began his third missionary journey by traveling all around the region of Galatia and Phrygia to strengthen, teach and rebuke the believers. Paul then traveled to Ephesus, an important center of early Christianity, and stayed there for almost three years, probably working there as a tentmaker,[145] as he had done when he stayed in Corinth. He is claimed to have performed numerous miracles, healing people and casting out demons, and he apparently organized missionary activity in other regions.[46] Paul left Ephesus after an attack from a local silversmith resulted in a pro-Artemis riot involving most of the city.[46] During his stay in Ephesus, Paul wrote four letters to the church in Corinth.[146] The Jerusalem Bible suggests that the letter to the church in Philippi was also written from Ephesus.[147]

Paul went through Macedonia into Achaea[148] and stayed in Greece, probably Corinth, for three months[148] during 56–57 AD.[46] Commentators generally agree that Paul dictated his Epistle to the Romans during this period.[149] He then made ready to continue on to Syria, but he changed his plans and traveled back through Macedonia because of some Jews who had made a plot against him. In Romans 15:19,[150] Paul wrote that he visited Illyricum, but he may have meant what would now be called Illyria Graeca,[151] which was at that time a division of the Roman province of Macedonia.[152] On their way back to Jerusalem, Paul and his companions visited other cities such as Philippi, Troas, Miletus, Rhodes, and Tyre. Paul finished his trip with a stop in Caesarea, where he and his companions stayed with Philip the Evangelist before finally arriving at Jerusalem.[153]

Journey from Rome to Spain

Among the writings of the early Christians, Pope Clement I said that Paul was "Herald (of the Gospel of Christ) in the West", and that "he had gone to the extremity of the west".[154] John Chrysostom indicated that Paul preached in Spain: "For after he had been in Rome, he returned to Spain, but whether he came thence again into these parts, we know not".[155] Cyril of Jerusalem said that Paul, "fully preached the Gospel, and instructed even imperial Rome, and carried the earnestness of his preaching as far as Spain, undergoing conflicts innumerable, and performing Signs and wonders".[156] The Muratorian fragment mentions "the departure of Paul from the city (39) when he journeyed to Spain".[157]

Visits to Jerusalem in Acts and the epistles

This table is adapted from White, From Jesus to Christianity.[123] Note that the matching of Paul's travels in the Acts and the travels in his Epistles is done for the reader's convenience and is not approved of by all scholars.

| Acts | Epistles |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last visit to Jerusalem and arrest

In 57 AD, upon completion of his third missionary journey, Paul arrived in Jerusalem for his fifth and final visit with a collection of money for the local community. The Acts of the Apostles reports that he initially was warmly received. However, Acts goes on to recount how Paul was warned by James and the elders that he was gaining a reputation for being against the Law, saying "they have been told about you that you teach all the Jews living among the Gentiles to forsake Moses, and that you tell them not to circumcise their children or observe the customs."[170] Paul underwent a purification ritual so that "all will know that there is nothing in what they have been told about you, but that you yourself observe and guard the law."[171]

When the seven days of the purification ritual were almost completed, some "Jews from Asia" (most likely from Roman Asia) accused Paul of defiling the temple by bringing gentiles into it. He was seized and dragged out of the temple by an angry mob. When the tribune heard of the uproar, he and some centurions and soldiers rushed to the area. Unable to determine his identity and the cause of the uproar, they placed him in chains.[172] He was about to be taken into the barracks when he asked to speak to the people. He was given permission by the Romans and proceeded to tell his story. After a while, the crowd responded. "Up to this point they listened to him, but then they shouted, 'Away with such a fellow from the earth! For he should not be allowed to live.'"[173] The tribune ordered that Paul be brought into the barracks and questioned by flogging. Paul asserted his Roman citizenship, which would prevent his flogging. The tribune "wanted to find out what Paul was being accused of by the Jews, the next day he released him and ordered the chief priests and the entire council to meet".[174] Paul spoke before the council and caused a disagreement between the Pharisees and the Sadducees. When this threatened to turn violent, the tribune ordered his soldiers to take Paul by force and return him to the barracks.[175]

The next morning, forty Jews "bound themselves by an oath neither to eat nor drink until they had killed Paul",[176] but the son of Paul's sister heard of the plot and notified Paul, who notified the tribune that the conspiracists were going to ambush him. The tribune ordered two centurions to "Get ready to leave by nine o'clock tonight for Caesarea with two hundred soldiers, seventy horsemen, and two hundred spearmen. Also provide mounts for Paul to ride, and take him safely to Felix the governor."[177]

Paul was taken to Caesarea, where the governor ordered that he be kept under guard in Herod's headquarters. "Five days later the high priest Ananias came down with some elders and an attorney, a certain Tertullus, and they reported their case against Paul to the governor."[178] Both Paul and the Jewish authorities gave a statement "But Felix, who was rather well informed about the Way, adjourned the hearing with the comment, "When Lysias the tribune comes down, I will decide your case."[179]

Marcus Antonius Felix then ordered the centurion to keep Paul in custody, but to "let him have some liberty and not to prevent any of his friends from taking care of his needs."[180] He was held there for two years by Felix, until a new governor, Porcius Festus, was appointed. The "chief priests and the leaders of the Jews" requested that Festus return Paul to Jerusalem. After Festus had stayed in Jerusalem "not more than eight or ten days, he went down to Caesarea; the next day he took his seat on the tribunal and ordered Paul to be brought." When Festus suggested that he be sent back to Jerusalem for further trial, Paul exercised his right as a Roman citizen to "appeal unto Caesar".[46] Finally, Paul and his companions sailed for Rome where Paul was to stand trial for his alleged crimes.[181]

Acts recounts that on the way to Rome for his appeal as a Roman citizen to Caesar, Paul was shipwrecked on "Melita" (Malta),[182] where the islanders showed him "unusual kindness" and where he was met by Publius.[183] From Malta, he travelled to Rome via Syracuse, Rhegium and Puteoli.[184]

Two years in Rome

Paul finally arrived in Rome around 60 AD, where he spent another two years under house arrest.[181] The narrative of Acts ends with Paul preaching in Rome for two years from his rented home while awaiting trial.[185]

Irenaeus wrote in the 2nd century that Peter and Paul had been the founders of the church in Rome and had appointed Linus as succeeding bishop.[186] However, Paul was not a bishop of Rome, nor did he bring Christianity to Rome since there were already Christians in Rome when he arrived there;[187] Paul also wrote his letter to the church at Rome before he had visited Rome.[188] Paul only played a supporting part in the life of the church in Rome.[189]

Death

The date of Paul's death is believed to have occurred after the Great Fire of Rome in July 64 AD, but before the last year of Nero's reign, in 68 AD.[2]

The Second Epistle to Timothy states that Paul was arrested in Troad[190] and brought back to Rome, where he was imprisoned and put on trial; the Epistle was traditionally ascribed to Paul, but today many scholars considered it to be pseudepigrapha, perhaps written by one of Paul's disciples.[191] Pope Clement I writes in his Epistle to the Corinthians that after Paul "had borne his testimony before the rulers", he "departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance."[192] Ignatius of Antioch writes in his Epistle to the Ephesians that Paul was martyred, without giving any further information.[193] Paul's supposed execution is not mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles.[46]

Eusebius states that Paul was killed during the Neronian Persecution[194] and, quoting from Dionysius of Corinth, argues that Peter and Paul were martyred "at the same time".[195] Tertullian writes that Paul was beheaded like John the Baptist,[196] a detail also contained in Lactantius,[197]Jerome,[198] John Chrysostom[199] and Sulpicius Severus.[200][full citation needed]

A legend later developed that his martyrdom occurred at the Aquae Salviae, on the Via Laurentina. According to this legend, after Paul was decapitated, his severed head rebounded three times, giving rise to a source of water each time that it touched the ground, which is how the place earned the name "San Paolo alle Tre Fontane" ("St Paul at the Three Fountains").[201][202] The apocryphal Acts of Paul also describe the martyrdom and the burial of Paul, but their narrative is highly fanciful and largely unhistorical.[203]

Remains

According to the Liber Pontificalis, Paul's body was buried outside the walls of Rome, at the second mile on the Via Ostiensis, on the estate owned by a Christian woman named Lucina.[204] It was here, in the fourth century, that the Emperor Constantine the Great built a first church. Then, between the fourth and fifth centuries, it was considerably enlarged by the Emperors Valentinian I, Valentinian II, Theodosius I, and Arcadius. The present-day Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls was built there in the early 19th century.[201]

Caius in his Disputation Against Proclus (198 AD) mentions this of the places in which the remains of the apostles Peter and Paul were deposited: "I can point out the trophies of the apostles. For if you are willing to go to the Vatican or to the Ostian Way, you will find the trophies of those who founded this Church".[205]

Jerome in his De Viris Illustribus (392 AD) writing on Paul's biography, mentions that "Paul was buried in the Ostian Way at Rome".[206]

In 2002, an 8-foot (2.4 m)-long marble sarcophagus, inscribed with the words "PAULO APOSTOLO MART" ("Paul apostle martyr") was discovered during excavations around the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls on the Via Ostiensis. Vatican archaeologists declared this to be the tomb of Paul the Apostle in 2005.[citation needed] In June 2009, Pope Benedict XVI announced excavation results concerning the tomb. The sarcophagus was not opened but was examined by means of a probe, which revealed pieces of incense, purple and blue linen, and small bone fragments. The bone was radiocarbon-dated to the 1st or 2nd century. According to the Vatican, these findings support the conclusion that the tomb is Paul's.[207][208]

Church tradition

Various Christian writers have suggested more details about Paul's life.

1 Clement, a letter written by the Roman bishop Clement of Rome around the year 90, reports this about Paul:

By reason of jealousy and strife Paul by his example pointed out the prize of patient endurance. After that he had been seven times in bonds, had been driven into exile, had been stoned, had preached in the East and in the West, he won the noble renown which was the reward of his faith, having taught righteousness unto the whole world and having reached the farthest bounds of the West; and when he had borne his testimony before the rulers, so he departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance.

— Lightfoot 1890, p. 274, The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians, 5:5–6

Commenting on this passage, Raymond Brown writes that while it "does not explicitly say" that Paul was martyred in Rome, "such a martyrdom is the most reasonable interpretation".[209] Eusebius of Caesarea, who wrote in the 4th century, states that Paul was beheaded in the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero.[205] This event has been dated either to the year 64 AD, when Rome was devastated by a fire, or a few years later, to 67 AD. According to one tradition, the church of San Paolo alle Tre Fontane marks the place of Paul's execution. A Roman Catholic liturgical solemnity of Peter and Paul, celebrated on 29 June, commemorates his martyrdom, and reflects a tradition (preserved by Eusebius) that Peter and Paul were martyred at the same time.[205] The Roman liturgical calendar for the following day now remembers all Christians martyred in these early persecutions; formerly, 30 June was the feast day for St. Paul.[210] Persons or religious orders with a special affinity for St. Paul can still celebrate their patron on 30 June.

The apocryphal Acts of Paul and the apocryphal Acts of Peter suggest that Paul survived Rome and traveled further west. Some think that Paul could have revisited Greece and Asia Minor after his trip to Spain, and might then have been arrested in Troas, and taken to Rome and executed.[211][note 4] A tradition holds that Paul was interred with Saint Peter ad Catacumbas by the via Appia until moved to what is now the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History, writes that Pope Vitalian in 665 gave Paul's relics (including a cross made from his prison chains) from the crypts of Lucina to King Oswy of Northumbria, northern Britain. The skull of Saint Paul is claimed to reside in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran since at least the ninth century, alongside the skull of Saint Peter.[212]

The Feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul is celebrated on 25 January.[213]

Paul is remembered (with Peter) in the Church of England with a Festival on 29 June.[214] Paul is considered the patron saint of London.

Physical appearance

The New Testament offers little if any information about the physical appearance of Paul, but several descriptions can be found in apocryphal texts. In the Acts of Paul[215] he is described as "A man of small stature, with a bald head and crooked legs, in a good state of body, with eyebrows meeting and nose somewhat hooked".[216] In the Latin version of the Acts of Paul and Thecla it is added that he had a red, florid face.

In The History of the Contending of Saint Paul, his countenance is described as "ruddy with the ruddiness of the skin of the pomegranate".[217] The Acts of Saint Peter confirms that Paul had a bald and shining head, with red hair.[218] As summarised by Barnes,[219] Chrysostom records that Paul's stature was low, his body crooked and his head bald. Lucian, in his Philopatris, describes Paul as "corpore erat parvo, contracto, incurvo, tricubitali" ("he was small, contracted, crooked, of three cubits, or four feet six").[32]

Nicephorus claims that Paul was a little man, crooked, and almost bent like a bow, with a pale countenance, long and wrinkled, and a bald head. Pseudo-Chrysostom echoes Lucian's height of Paul, referring to him as "the man of three cubits".[32]

Writings

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|