A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Ruhollah Khomeini | |

|---|---|

| روحالله خمینی | |

Official portrait, 1981 | |

| 1st Supreme Leader of Iran | |

| In office 3 December 1979 – 3 June 1989 | |

| President |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Deputy | Hussein-Ali Montazeri (1985–1989) |

| Preceded by | Position established (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as Shah of Iran) |

| Succeeded by | Ali Khamenei |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ruhollah Mostafavi Musavi 17 May 1900 or 24 September 1902[a] Khomeyn, Sublime State of Persia |

| Died | 3 June 1989 (aged 86 or 89) Tehran, Iran |

| Resting place | Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Spouse | |

| Relations | Khomeini family |

| Children | 7, including Mostafa, Zahra, Farideh, and Ahmad |

| Education | Qom Seminary |

| Signature |  |

| Website | imam-khomeini |

| Personal | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Twelver Shiʿa[1][2][3] |

| Creed | Usuli |

| Notable idea(s) | New advance of Guardianship |

| Notable work(s) | |

| Muslim leader | |

| Teacher | Seyyed Hossein Borujerdi |

| Styles of Ruhollah Khomeini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Eminent marji' al-taqlid, Ayatullah al-Uzma Imam Khumayni[4] |

| Spoken style | Imam Khomeini[5] |

| Religious style | Ayatullah al-Uzma Ruhollah Khomeini[5] |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Ayatollah Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini[b] (17 May 1900 or 24 September 1902[a] – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian Islamic revolutionary, politician, and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the main leader of the Iranian Revolution, which overthrew Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and ended the Iranian monarchy.

Born in Khomeyn, in what is now Iran's Markazi province, his father was murdered in 1903 when Khomeini was two years old. He began studying the Quran and Arabic from a young age and was assisted in his religious studies by his relatives, including his mother's cousin and older brother. Khomeini was a high ranking cleric in Twelver Shi'ism, an ayatollah, a marja' ("source of emulation"), a Mujtahid or faqīh (an expert in sharia), and author of more than 40 books. His opposition to the White Revolution resulted in his state-sponsored expulsion to Bursa in 1964. Nearly a year later, he moved to Najaf, where speeches he gave outlining his religiopolitical theory of Guardianship of the Jurist were compiled into Islamic Government.

He was Time magazine's Man of the Year in 1979 for his international influence, and Khomeini has been described as the "virtual face of Shia Islam in Western popular culture", where he was known for his support of the hostage takers during the Iran hostage crisis, his fatwa calling for the murder of British Indian novelist Salman Rushdie, and for referring to the United States as the "Great Satan" and the Soviet Union as the "Lesser Satan". Following the revolution, Khomeini became the country's first supreme leader, a position created in the constitution of the Islamic Republic as the highest-ranking political and religious authority of the nation, which he held until his death. Most of his period in power was taken up by the Iran–Iraq War of 1980–1988. He was succeeded by Ali Khamenei on 4 June 1989.

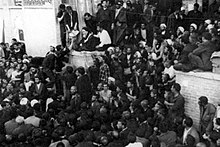

The subject of a pervasive cult of personality, Khomeini is officially known as Imam Khomeini inside Iran and by his supporters internationally. His funeral was attended by up to 10 million people, or 1/6 of Iran's population, the largest funeral at the time and one of the largest human gatherings in history. In Iran, his gold-domed tomb in Tehran's Behesht-e Zahrāʾ cemetery has become a shrine for his adherents, and he is legally considered "inviolable", with Iranians regularly punished for insulting him. His supporters view him as a champion of Islamic revival, anti-racism and anti-imperialism. Critics accuse him of human rights violations (including his ordering of attacks against demonstrators, and execution of thousands of political prisoners, war criminals and prisoners of the Iran–Iraq War), as well as for using child soldiers extensively during the Iran–Iraq War for human wave attacks—estimates are as high as 100,000 for the number of children killed.

Early years

Background

Ruhollah Khomeini came from a lineage of small land owners, clerics, and merchants.[6] His ancestors migrated towards the end of the 18th century from their original home in Nishapur, Khorasan province in northeastern Iran for a short stay to the Kingdom of Awadh, a region in the modern state of Uttar Pradesh, India, whose rulers were Twelver Shia Muslims of Persian origin.[7][8][9] During their rule they extensively invited, and received, a steady stream of Persian scholars, poets, jurists, architects, and painters.[10] The family eventually settled in the small town of Kintoor, near Lucknow, the capital of Awadh.[11][12][13][14] Ayatollah Khomeini's paternal grandfather, Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi, was born in Kintoor.[12][14] He left Lucknow in 1830, on a pilgrimage to the tomb of Ali in Najaf, Ottoman Iraq (now Iraq) and never returned.[11][14] According to Moin, this migration was to escape from the spread of British power in India.[15] In 1834 Seyyed Ahmad Musavi Hindi visited Persia, and in 1839 he settled in Khomein.[12] Although he stayed and settled in Iran, he continued to be known as Hindi, indicating his stay in India, and Ruhollah Khomeini even used Hindi as a pen name in some of his ghazals.[11] Khomeini's grandfather, Mirza Ahmad Mojtahed-e Khonsari was the cleric issuing a fatwa to forbid usage of tobacco during the Tobacco Protest.[16][17]

Childhood

According to his birth certificate, Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, whose first name means "spirit of Allah", was born on 17 May 1900 in Khomeyn, Markazi Province although his brother Mortaza (later known as Ayatollah Pasandideh) gives his birth date of 24 September 1902, the birth anniversary of Muhammad's daughter, Fatima.[18][19] He was raised by his mother, Agha Khanum, and his aunt, Sahebeth, following the murder of his father, Mustafa Musawi, over two years after his birth in 1903.[20]

Ruhollah began to study the Qur'an and elementary Persian at the age of six.[21] The following year, he began to attend a local school, where he learned religion, noheh khani (lamentation recital), and other traditional subjects.[15] Throughout his childhood, he continued his religious education with the assistance of his relatives, including his mother's cousin, Ja'far,[15] and his elder brother, Morteza Pasandideh.[22]

Education and lecturing

After the First World War, arrangements were made for him to study at the Islamic seminary in Isfahan, but he was attracted instead to the seminary in Arak. He was placed under the leadership of Ayatollah Abdolkarim Haeri Yazdi.[23] In 1920, Khomeini moved to Arak and commenced his studies.[24] The following year, Ayatollah Haeri Yazdi transferred to the Islamic seminary in the holy city of Qom, southwest of Tehran, and invited his students to follow. Khomeini accepted the invitation, moved,[22] and took up residence at the Dar al-Shafa school in Qom.[25] Khomeini's studies included Islamic law (sharia) and jurisprudence (fiqh),[21] but by that time, Khomeini had also acquired an interest in poetry and philosophy (irfan). So, upon arriving in Qom, Khomeini sought the guidance of Mirza Ali Akbar Yazdi, a scholar of philosophy and mysticism. Yazdi died in 1924, but Khomeini continued to pursue his interest in philosophy with two other teachers, Javad Aqa Maleki Tabrizi and Rafi'i Qazvini.[26][27] However, perhaps Khomeini's biggest influences were another teacher, Mirza Muhammad 'Ali Shahabadi,[28] and a variety of historic Sufi mystics, including Mulla Sadra and Ibn Arabi.[27]

Khomeini studied ancient Greek philosophy and was influenced by both the philosophy of Aristotle, whom he regarded as the founder of logic,[29] and Plato, whose views "in the field of divinity" he regarded as "grave and solid".[30] Among Islamic philosophers, Khomeini was mainly influenced by Avicenna and Mulla Sadra.[29]

Apart from philosophy, Khomeini was interested in literature and poetry. His poetry collection was released after his death. Beginning in his adolescent years, Khomeini composed mystic, political and social poetry. His poetry works were published in three collections: The Confidant, The Decanter of Love and Turning Point, and Divan.[31] His knowledge of poetry is further attested by the modern poet Nader Naderpour (1929–2000), who "had spent many hours exchanging poems with Khomeini in the early 1960s". Naderpour remembered: "For four hours we recited poetry. Every single line I recited from any poet, he recited the next."[32]

Ruhollah Khomeini was a lecturer at Najaf and Qom seminaries for decades before he was known on the political scene. He soon became a leading scholar of Shia Islam.[33] He taught political philosophy,[34] Islamic history and ethics. Several of his students – for example, Morteza Motahhari – later became leading Islamic philosophers and also marja'. As a scholar and teacher, Khomeini produced numerous writings on Islamic philosophy, law, and ethics.[35] He showed an exceptional interest in subjects like philosophy and mysticism that not only were usually absent from the curriculum of seminaries but were often an object of hostility and suspicion.[36]

Inaugurating his teaching career at the age of 27 by giving private lessons on irfan and Mulla Sadra to a private circle, around the same time, in 1928, he also released his first publication, Sharh Du'a al-Sahar (Commentary on the Du'a al-Baha), "a detailed commentary, in Arabic, on the prayer recited before dawn during Ramadan by Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq", followed, some years later, by Sirr al-Salat (Secret of the Prayer), where "the symbolic dimensions and inner meaning of every part of the prayer, from the ablution that precedes it to the salam that concludes it, are expounded in a rich, complex, and eloquent language that owes much to the concepts and terminology of Ibn 'Arabi. As Sayyid Fihri, the editor and translator of Sirr al-Salat, has remarked, the work is addressed only to the foremost among the spiritual elite (akhass-i khavass) and establishes its author as one of their number."[37] The second book has been translated by Sayyid Amjad Hussain Shah Naqavi and released by Brill in 2015, under the title "The Mystery of Prayer: The Ascension of the Wayfarers and the Prayer of the Gnostics Archived 6 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine".

Political aspects

His seminary teaching often focused on the importance of religion to practical social and political issues of the day, and he worked against secularism in the 1940s. His first political book, Kashf al-Asrar (Uncovering of Secrets)[38][39] published in 1942, was a point-by-point refutation of Asrar-e Hezar Sale (Secrets of a Thousand Years), a tract written by a disciple of Iran's leading anti-clerical historian, Ahmad Kasravi,[40] as well as a condemnation of innovations such as international time zones,[c][non-primary source needed] and the banning of hijab by Reza Shah. In addition, he went from Qom to Tehran to listen to Ayatullah Hasan Mudarris, the leader of the opposition majority in Iran's parliament during the 1920s. Khomeini became a marja' in 1963, following the death of Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Husayn Borujerdi.

Khomeini also valued the ideals of Islamists such as Sheikh Fazlollah Noori and Abol-Ghasem Kashani. Khomeini saw Fazlollah Nuri as a "heroic figure", and his own objections to constitutionalism and a secular government derived from Nuri's objections to the 1907 constitution.[41][42][43]

Early political activity

Background

In the late 19th century, the clergy had shown themselves to be a powerful political force in Iran initiating the Tobacco Protest against a concession to a foreign (British) interest.[44]

At the age of 61, Khomeini found the arena of leadership open following the deaths of Ayatollah Sayyed Husayn Borujerdi (1961), the leading, although quiescent, Shi'ah religious leader; and Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani (1962), an activist cleric. The clerical class had been on the defensive ever since the 1920s when the secular, anti-clerical modernizer Reza Shah Pahlavi rose to power. Reza's son Mohammad Reza Shah instituted the White Revolution, which was a further challenge to the Ulama.[45]

Opposition to the White Revolution

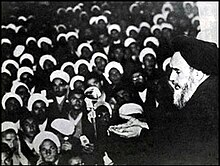

In January 1963, the Shah announced the White Revolution, a six-point programme of reform calling for land reform, nationalization of the forests, the sale of state-owned enterprises to private interests, electoral changes to enfranchise women and allow non-Muslims to hold office, profit-sharing in industry, and a literacy campaign in the nation's schools. Some of these initiatives were regarded as dangerous, especially by the powerful and privileged Shi'a ulama (religious scholars), and as Westernizing trends by traditionalists. Khomeini viewed them as "an attack on Islam".[46] Ayatollah Khomeini summoned a meeting of the other senior marjas of Qom and persuaded them to decree a boycott of the referendum on the White Revolution. On 22 January 1963, Khomeini issued a strongly worded declaration denouncing both the Shah and his reform plan. Two days later, the Shah took an armored column to Qom, and delivered a speech harshly attacking the ulama as a class.

Khomeini continued his denunciation of the Shah's programmes, issuing a manifesto that bore the signatures of eight other senior Shia religious scholars. Khomeini's manifesto argued that the Shah had violated the constitution in various ways, he condemned the spread of moral corruption in the country, and accused the Shah of submission to the United States and Israel. He also decreed that the Nowruz celebrations for the Iranian year 1342 (which fell on 21 March 1963) be canceled as a sign of protest against government policies.

On the afternoon of 'Ashura (3 June 1963), Khomeini delivered a speech at the Feyziyeh madrasah drawing parallels between the Caliph Yazid, who is perceived as a 'tyrant' by Shias, and the Shah, denouncing the Shah as a "wretched, miserable man," and warning him that if he did not change his ways the day would come when the people would offer up thanks for his departure from the country.

On 5 June 1963 (15 of Khordad) at 3:00 am, two days after this public denunciation of the Shah, Khomeini was detained in Qom and transferred to Tehran.[47] Following this action, there were three days of major riots throughout Iran and the deaths of some 400 people. That event is now referred to as the Movement of 15 Khordad.[48] Khomeini remained under house arrest until August.[49][50]

Opposition to capitulation

On 26 October 1964, Khomeini denounced both the Shah and the United States. This time it was in response to the "capitulations" or diplomatic immunity granted by the Shah to American military personnel in Iran.[51][52] What Khomeini labeled a capitulation law, was in fact a "status-of-forces agreement", stipulating that U.S. servicemen facing criminal charges stemming from a deployment in Iran, were to be tried before a U.S. court martial, not an Iranian court. Khomeini was arrested in November 1964 and held for half a year. Upon his release, Khomeini was brought before Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansur, who tried to convince him to apologize for his harsh rhetoric and going forward, cease his opposition to the Shah and his government. When Khomeini refused, Mansur slapped him in the face in a fit of rage. Two months later, Mansur was assassinated on his way to parliament. Four members of the Fadayan-e Islam, a Shia militia sympathetic to Khomeini, were later executed for the murder.[53]

Life in exile

Khomeini spent more than 14 years in exile, mostly in the holy Iraqi city of Najaf. Initially, he was sent to Turkey on 4 November 1964 where he stayed in Bursa in the home of Colonel Ali Cetiner of the Turkish Military Intelligence.[54] In October 1965, after less than a year, he was allowed to move to Najaf, Iraq, where he stayed until 1978, when he was expelled[55] by then-Vice President Saddam Hussein. By this time discontent with the Shah was becoming intense and Khomeini visited Neauphle-le-Château, a suburb of Paris, France, on a tourist visa on 6 October 1978.[35][56][57]

By the late 1960s, Khomeini was a marja-e taqlid (model for imitation) for "hundreds of thousands" of Shia, one of six or so models in the Shia world.[58] While in the 1940s Khomeini accepted the idea of a limited monarchy under the Persian Constitution of 1906 – as evidenced by his book Kashf al-Asrar – by the 1970s he had rejected the idea. In early 1970, Khomeini gave a series of lectures in Najaf on Islamic government, later published as a book titled variously Islamic Government or Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist (Hokumat-e Islami: Velayat-e faqih). This principle, though not known to the wider public before the revolution,[59][60] was appended to the new Iranian constitution after the revolution.[61][62]

- Velayat-e faqih

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.