A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Hypnosis | |

|---|---|

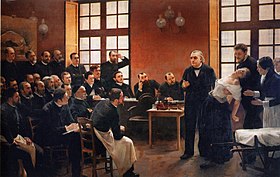

Jean-Martin Charcot demonstrating hypnosis on a "hysterical" Salpêtrière patient, "Blanche" (Marie Wittman), who is supported by Joseph Babiński[1] | |

| MeSH | D006990 |

| Hypnosis |

|---|

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI),[2] reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.[3]

There are competing theories explaining hypnosis and related phenomena. Altered state theories see hypnosis as an altered state of mind or trance, marked by a level of awareness different from the ordinary state of consciousness.[4][5] In contrast, non-state theories see hypnosis as, variously, a type of placebo effect,[6][7] a redefinition of an interaction with a therapist[8] or a form of imaginative role enactment.[9][10][11]

During hypnosis, a person is said to have heightened focus and concentration[12][13] and an increased response to suggestions.[14] Hypnosis usually begins with a hypnotic induction involving a series of preliminary instructions and suggestions. The use of hypnosis for therapeutic purposes is referred to as "hypnotherapy[15]", while its use as a form of entertainment for an audience is known as "stage hypnosis", a form of mentalism.

Hypnosis-based therapies for the management of irritable bowel syndrome and menopause are supported by evidence.[16][17][18][19] Use of hypnosis for treatment of other problems has produced mixed results, such as with smoking cessation.[20][21][22] The use of hypnosis as a form of therapy to retrieve and integrate early trauma is controversial within the scientific mainstream. Research indicates that hypnotising an individual may aid the formation of false memories,[23][24] and that hypnosis "does not help people recall events more accurately".[25] Medical hypnosis is often considered pseudoscience or quackery.[26]

Etymology

The words hypnosis and hypnotism both derive from the term neuro-hypnotism (nervous sleep), all of which were coined by Étienne Félix d'Henin de Cuvillers in the 1820s. The term hypnosis is derived from the ancient Greek ὑπνος hypnos, "sleep", and the suffix -ωσις -osis, or from ὑπνόω hypnoō, "put to sleep" (stem of aorist hypnōs-) and the suffix -is.[27][28] These words were popularised in English by the Scottish surgeon James Braid (to whom they are sometimes wrongly attributed) around 1841. Braid based his practice on that developed by Franz Mesmer and his followers (which was called "Mesmerism" or "animal magnetism"), but differed in his theory as to how the procedure worked.

History

Precursors

People have been entering into hypnotic-type trances for thousands of years. In many cultures and religions, it was regarded as a form of meditation. The earliest record of a description of a hypnotic state can be found in the writings of Avicenna, a Persian physician who wrote about "trance" in 1027.[2] Modern-day hypnosis started in the late 18th century and was made popular by Franz Mesmer, a German physician who became known as the father of "modern hypnotism". Hypnosis was known at the time as "Mesmerism" being named after Mesmer.

Mesmer held the opinion that hypnosis was a sort of mystical force that flows from the hypnotist to the person being hypnotised, but his theory was dismissed by critics who asserted that there is no magical element to hypnotism.

Abbé Faria, a Luso-Goan Catholic monk, was one of the pioneers of the scientific study of hypnotism, following on from the work of Franz Mesmer. Unlike Mesmer, who claimed that hypnosis was mediated by "animal magnetism", Faria believed that it worked purely by the power of suggestion.[29][30]

Before long, hypnotism started finding its way into the world of modern medicine. The use of hypnotism in the medical field was made popular by surgeons and physicians like Elliotson and James Esdaile and researchers like James Braid who helped to reveal the biological and physical benefits of hypnotism.[31][self-published source] According to his writings, Braid began to hear reports concerning various Oriental meditative practices soon after the release of his first publication on hypnotism, Neurypnology (1843). He first discussed some of these oriental practices in a series of articles entitled Magic, Mesmerism, Hypnotism, etc., Historically & Physiologically Considered. He drew analogies between his own practice of hypnotism and various forms of Hindu yoga meditation and other ancient spiritual practices, especially those involving voluntary burial and apparent human hibernation. Braid's interest in these practices stems from his studies of the Dabistān-i Mazāhib, the "School of Religions", an ancient Persian text describing a wide variety of Oriental religious rituals, beliefs, and practices.

Last May , a gentleman residing in Edinburgh, personally unknown to me, who had long resided in India, favored me with a letter expressing his approbation of the views which I had published on the nature and causes of hypnotic and mesmeric phenomena. In corroboration of my views, he referred to what he had previously witnessed in oriental regions, and recommended me to look into the Dabistan, a book lately published, for additional proof to the same effect. On much recommendation I immediately sent for a copy of the Dabistan, in which I found many statements corroborative of the fact, that the eastern saints are all self-hypnotisers, adopting means essentially the same as those which I had recommended for similar purposes.[32]

Although he rejected the transcendental/metaphysical interpretation given to these phenomena outright, Braid accepted that these accounts of Oriental practices supported his view that the effects of hypnotism could be produced in solitude, without the presence of any other person (as he had already proved to his own satisfaction with the experiments he had conducted in November 1841), and he saw correlations between many of the "metaphysical" Oriental practices and his own "rational" neuro-hypnotism, and totally rejected all of the fluid theories and magnetic practices of the mesmerists. As he later wrote:

In as much as patients can throw themselves into the nervous sleep, and manifest all the usual phenomena of Mesmerism, through their own unaided efforts, as I have so repeatedly proved by causing them to maintain a steady fixed gaze at any point, concentrating their whole mental energies on the idea of the object looked at; or that the same may arise by the patient looking at the point of his own finger, or as the Magi of Persia and Yogi of India have practised for the last 2,400 years, for religious purposes, throwing themselves into their ecstatic trances by each maintaining a steady fixed gaze at the tip of his own nose; it is obvious that there is no need for an exoteric influence to produce the phenomena of Mesmerism. ... The great object in all these processes is to induce a habit of abstraction or concentration of attention, in which the subject is entirely absorbed with one idea, or train of ideas, whilst he is unconscious of, or indifferently conscious to, every other object, purpose, or action.[33]

Avicenna

Avicenna (980–1037), a Persian physician, documented the characteristics of the "trance" (hypnotic trance) state in 1027. At that time, hypnosis as a medical treatment was seldom used; the German doctor Franz Mesmer reintroduced it in the 18th century.[34]

Franz Mesmer

Franz Mesmer (1734–1815) believed that there is a magnetic force or "fluid" called "animal magnetism" within the universe that influences the health of the human body. He experimented with magnets to affect this field in order to produce healing. By around 1774, he had concluded that the same effect could be created by passing the hands in front of the subject's body, later referred to as making "Mesmeric passes".[35]

In 1784, at the request of King Louis XVI, two Royal Commissions on Animal Magnetism were specifically charged with (separately) investigating the claims made by one Charles d'Eslon (1750–1786), a disaffected student of Mesmer, for the existence of a substantial (rather than metaphorical, as Mesmer supposed) "animal magnetism", 'le magnétisme animal', and of a similarly physical "magnetic fluid", 'le fluide magnétique'. Among the investigators were the scientist, Antoine Lavoisier, an expert in electricity and terrestrial magnetism, Benjamin Franklin, and an expert in pain control, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin.

The Commissioners investigated the practices of d'Eslon, and, although they accepted, without question, that Mesmer's "cures" were, indeed, "cures", they did not investigate whether (or not) Mesmer was the agent of those "cures". Significantly, in their investigations of d'Eslon's procedures, they conducted an expansive series of randomized controlled trials, the experimental protocols of which were designed by Lavoisier, including the application of both "sham" and "genuine" procedures and, significantly, the first use of "blindfolding" of both the investigators and their subjects.

From their investigations, both Commissions concluded that there was no evidence of any kind to support d'Eslon's claim for the substantial physical existence of either his supposed "animal magnetism" or his supposed "magnetic fluid", and, in the process, they determined that all of the effects they had observed could be directly attributed to a physiological (rather than metaphysical) agency—namely, that all of the experimentally observed phenomena could be directly attributed to "contact", "imagination", and/or "imitation".

Eventually, Mesmer left Paris and went back to Vienna to practise mesmerism.

James Braid

Following the French committee's findings, Dugald Stewart, an influential academic philosopher of the "Scottish School of Common Sense", encouraged physicians in his Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind (1818)[37] to salvage elements of Mesmerism by replacing the supernatural theory of "animal magnetism" with a new interpretation based upon "common sense" laws of physiology and psychology. Braid quotes the following passage from Stewart:[38]

It appears to me, that the general conclusions established by Mesmer's practice, with respect to the physical effects of the principle of imagination (more particularly in cases where they co-operated together), are incomparably more curious than if he had actually demonstrated the existence of his boasted science : nor can I see any good reason why a physician, who admits the efficacy of the moral agents employed by Mesmer, should, in the exercise of his profession, scruple to copy whatever processes are necessary for subjecting them to his command, any more than that he should hesitate about employing a new physical agent, such as electricity or galvanism.[37]

In Braid's day, the Scottish School of Common Sense provided the dominant theories of academic psychology, and Braid refers to other philosophers within this tradition throughout his writings. Braid therefore revised the theory and practice of mesmerism and developed his own method of hypnotism as a more rational and common sense alternative.

It may here be requisite for me to explain, that by the term Hypnotism, or Nervous Sleep, which frequently occurs in the following pages, I mean a peculiar condition of the nervous system, into which it may be thrown by artificial contrivance, and which differs, in several respects, from common sleep or the waking condition. I do not allege that this condition is induced through the transmission of a magnetic or occult influence from my body into that of my patients; nor do I profess, by my processes, to produce the higher phenomena of the Mesmerists. My pretensions are of a much more humble character, and are all consistent with generally admitted principles in physiological and psychological science. Hypnotism might therefore not inaptly be designated, Rational Mesmerism, in contra-distinction to the Transcendental Mesmerism of the Mesmerists.[39]

as discussed in his Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind[40]

Despite briefly toying with the name "rational mesmerism" — in "contra-distinction" to the entirely different "transcendental mesmerism" of the mesmerists[41] — and, eventually, deciding that psycho-physiology was a far more appropriate, and far more usefully descriptive name than hypnotism,[42] Braid ultimately chose to emphasise the unique aspects of his approach, firmly based upon the "dominant idea" theories of his Edinburgh University teacher, the philosopher Thomas Brown, M.D.,[43][44] carrying out informal experiments throughout his career — in order to refute theories and practices that invoked (supposed) supernatural forces — that demonstrated the role of ordinary physiological and psychological processes, such as suggestion and focused attention in producing the observed effects.

Braid worked very closely with his friend and ally the eminent physiologist Professor William Benjamin Carpenter, an early neuro-psychologist who introduced the "ideo-motor reflex" theory of suggestion. Carpenter had observed instances of expectation and imagination apparently influencing involuntary muscle movement. A classic example of the ideo-motor principle in action is the so-called "Chevreul pendulum" (named after Michel Eugène Chevreul). Chevreul claimed that divinatory pendulae were made to swing by unconscious muscle movements brought about by focused concentration alone.

Braid soon assimilated Carpenter's observations into his own theory, realising that the effect of focusing attention was to enhance the ideo-motor reflex response. Braid extended Carpenter's theory to encompass the influence of the mind upon the body more generally, beyond the muscular system, and therefore referred to the "ideo-dynamic" response and coined the term "psycho-physiology" to refer to the study of general mind/body interaction.

In his later works, Braid reserved the term "hypnotism" for cases in which subjects entered a state of amnesia resembling sleep. For other cases, he spoke of a "mono-ideodynamic" principle to emphasise that the eye-fixation induction technique worked by narrowing the subject's attention to a single idea or train of thought ("monoideism"), which amplified the effect of the consequent "dominant idea" upon the subject's body by means of the ideo-dynamic principle.[45]

Hysteria vs. suggestion

For several decades, Braid's work became more influential abroad than in his own country, except for a handful of followers, most notably Dr. John Milne Bramwell. The eminent neurologist Dr. George Miller Beard took Braid's theories to America. Meanwhile, his works were translated into German by William Thierry Preyer, Professor of Physiology at Jena University. The psychiatrist Albert Moll subsequently continued German research, publishing Hypnotism in 1889. France became the focal point for the study of Braid's ideas after the eminent neurologist Dr. Étienne Eugène Azam translated Braid's last manuscript (On Hypnotism, 1860) into French and presented Braid's research to the French Academy of Sciences. At the request of Azam, Paul Broca, and others, the French Academy of Science, which had investigated Mesmerism in 1784, examined Braid's writings shortly after his death.[46]

Azam's enthusiasm for hypnotism influenced Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault, a country doctor. Hippolyte Bernheim discovered Liébeault's enormously popular group hypnotherapy clinic and subsequently became an influential hypnotist. The study of hypnotism subsequently revolved around the fierce debate between Bernheim and Jean-Martin Charcot, the two most influential figures in late 19th-century hypnotism.

Charcot operated a clinic at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital (thus, known as the "Paris School" or the "Salpêtrière School"), while Bernheim had a clinic in Nancy (known as the "Nancy School"). Charcot, who was influenced more by the Mesmerists, argued that hypnotism was an abnormal state of nervous functioning found only in certain hysterical women. He claimed that it manifested in a series of physical reactions that could be divided into distinct stages. Bernheim argued that anyone could be hypnotised, that it was an extension of normal psychological functioning, and that its effects were due to suggestion. After decades of debate, Bernheim's view dominated. Charcot's theory is now just a historical curiosity.[47]

Pierre Janet

Pierre Janet (1859–1947) reported studies on a hypnotic subject in 1882. Charcot subsequently appointed him director of the psychological laboratory at the Salpêtrière in 1889, after Janet had completed his PhD, which dealt with psychological automatism. In 1898, Janet was appointed psychology lecturer at the Sorbonne, and in 1902 he became chair of experimental and comparative psychology at the Collège de France.[48] Janet reconciled elements of his views with those of Bernheim and his followers, developing his own sophisticated hypnotic psychotherapy based upon the concept of psychological dissociation, which, at the turn of the century, rivalled Freud's attempt to provide a more comprehensive theory of psychotherapy.

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the founder of psychoanalysis, studied hypnotism at the Paris School and briefly visited the Nancy School.

At first, Freud was an enthusiastic proponent of hypnotherapy. He "initially hypnotised patients and pressed on their foreheads to help them concentrate while attempting to recover (supposedly) repressed memories",[49] and he soon began to emphasise hypnotic regression and ab reaction (catharsis) as therapeutic methods. He wrote a favorable encyclopedia article on hypnotism, translated one of Bernheim's works into German, and published an influential series of case studies with his colleague Joseph Breuer entitled Studies on Hysteria (1895). This became the founding text of the subsequent tradition known as "hypno-analysis" or "regression hypnotherapy".

However, Freud gradually abandoned hypnotism in favour of psychoanalysis, emphasising free association and interpretation of the unconscious. Struggling with the great expense of time that psychoanalysis required, Freud later suggested that it might be combined with hypnotic suggestion to hasten the outcome of treatment, but that this would probably weaken the outcome: "It is very probable, too, that the application of our therapy to numbers will compel us to alloy the pure gold of analysis plentifully with the copper of direct suggestion."[50]

Only a handful of Freud's followers, however, were sufficiently qualified in hypnosis to attempt the synthesis. Their work had a limited influence on the hypno-therapeutic approaches now known variously as "hypnotic regression", "hypnotic progression", and "hypnoanalysis".

Émile Coué

Émile Coué (1857–1926) assisted Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault for around two years at Nancy. After practising for several months employing the "hypnosis" of Liébeault and Bernheim's Nancy School, he abandoned their approach altogether. Later, Coué developed a new approach (c.1901) based on Braid-style "hypnotism", direct hypnotic suggestion, and ego-strengthening which eventually became known as La méthode Coué.[51] According to Charles Baudouin, Coué founded what became known as the New Nancy School, a loose collaboration of practitioners who taught and promoted his views.[52][53] Coué's method did not emphasise "sleep" or deep relaxation, but instead focused upon autosuggestion involving a specific series of suggestion tests. Although Coué argued that he was no longer using hypnosis, followers such as Charles Baudouin viewed his approach as a form of light self-hypnosis. Coué's method became a renowned self-help and psychotherapy technique, which contrasted with psychoanalysis and prefigured self-hypnosis and cognitive therapy.

Clark L. Hull

The next major development came from behavioural psychology in American university research. Clark L. Hull (1884–1952), an eminent American psychologist, published the first major compilation of laboratory studies on hypnosis, Hypnosis & Suggestibility (1933), in which he proved that hypnosis and sleep had nothing in common. Hull published many quantitative findings from hypnosis and suggestion experiments and encouraged research by mainstream psychologists. Hull's behavioural psychology interpretation of hypnosis, emphasising conditioned reflexes, rivalled the Freudian psycho-dynamic interpretation which emphasised unconscious transference.

Dave Elman

Although Dave Elman (1900–1967) was a noted radio host, comedian, and songwriter, he also made a name as a hypnotist. He led many courses for physicians, and in 1964 wrote the book Findings in Hypnosis, later to be retitled Hypnotherapy (published by Westwood Publishing). Perhaps the most well-known aspect of Elman's legacy is his method of induction, which was originally fashioned for speed work and later adapted for the use of medical professionals.

Milton Erickson

Milton Erickson (1901–1980), the founding president of the American Society for Clinical Hypnosis and a fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Psychopathological Association, was one of the most influential post-war hypnotherapists. He wrote several books and journal articles on the subject. During the 1960s, Erickson popularised a new branch of hypnotherapy, known as Ericksonian therapy, characterised primarily by indirect suggestion, "metaphor" (actually analogies), confusion techniques, and double binds in place of formal hypnotic inductions. However, the difference between Erickson's methods and traditional hypnotism led contemporaries such as André Weitzenhoffer to question whether he was practising "hypnosis" at all, and his approach remains in question.

Erickson had no hesitation in presenting any suggested effect as being "hypnosis", whether or not the subject was in a hypnotic state. In fact, he was not hesitant in passing off behaviour that was dubiously hypnotic as being hypnotic.[54]

But during numerous witnessed and recorded encounters in clinical, experimental, and academic settings Erickson was able to evoke examples of classic hypnotic phenomena such as positive and negative hallucinations, anesthesia, analgesia (in childbirth and even terminal cancer patients), catalepsy, regression to provable events in subjects' early lives and even into infantile reflexology. Erickson stated in his own writings that there was no correlation between hypnotic depth and therapeutic success and that the quality of the applied psychotherapy outweighed the need for deep hypnosis in many cases. Hypnotic depth was to be pursued for research purposes.[55]

Cognitive-behavioural

In the latter half of the 20th century, two factors contributed to the development of the cognitive-behavioural approach to hypnosis:

- Cognitive and behavioural theories of the nature of hypnosis (influenced by the theories of Sarbin[56] and Barber[57]) became increasingly influential.

- The therapeutic practices of hypnotherapy and various forms of cognitive behavioural therapy overlapped and influenced each other.[58][59]

Although cognitive-behavioural theories of hypnosis must be distinguished from cognitive-behavioural approaches to hypnotherapy, they share similar concepts, terminology, and assumptions and have been integrated by influential researchers and clinicians such as Irving Kirsch, Steven Jay Lynn, and others.[60]

At the outset of cognitive behavioural therapy during the 1950s, hypnosis was used by early behaviour therapists such as Joseph Wolpe[61] and also by early cognitive therapists such as Albert Ellis.[62] Barber, Spanos, and Chaves introduced the term "cognitive-behavioural" to describe their "nonstate" theory of hypnosis in Hypnosis, imagination, and human potentialities.[57] However, Clark L. Hull had introduced a behavioural psychology as far back as 1933, which in turn was preceded by Ivan Pavlov.[63] Indeed, the earliest theories and practices of hypnotism, even those of Braid, resemble the cognitive-behavioural orientation in some respects.[59][64]

Definition

A person in a state of hypnosis has focused attention, and has increased suggestibility.[65]

The hypnotized individual appears to heed only the communications of the hypnotist and typically responds in an uncritical, automatic fashion while ignoring all aspects of the environment other than those pointed out by the hypnotist. In a hypnotic state an individual tends to see, feel, smell, and otherwise perceive in accordance with the hypnotist's suggestions, even though these suggestions may be in apparent contradiction to the actual stimuli present in the environment. The effects of hypnosis are not limited to sensory change; even the subject's memory and awareness of self may be altered by suggestion, and the effects of the suggestions may be extended (post-hypnotically) into the subject's subsequent waking activity.[66]

It could be said that hypnotic suggestion is explicitly intended to make use of the placebo effect. For example, in 1994, Irving Kirsch characterized hypnosis as a "non-deceptive placebo", i.e., a method that openly makes use of suggestion and employs methods to amplify its effects.[6][7]

A definition of hypnosis, derived from academic psychology, was provided in 2005, when the Society for Psychological Hypnosis, Division 30 of the American Psychological Association (APA), published the following formal definition:

Hypnosis typically involves an introduction to the procedure during which the subject is told that suggestions for imaginative experiences will be presented. The hypnotic induction is an extended initial suggestion for using one's imagination, and may contain further elaborations of the introduction. A hypnotic procedure is used to encourage and evaluate responses to suggestions. When using hypnosis, one person (the subject) is guided by another (the hypnotist) to respond to suggestions for changes in subjective experience, alterations in perception,[67][68] sensation,[69] emotion, thought or behavior. Persons can also learn self-hypnosis, which is the act of administering hypnotic procedures on one's own. If the subject responds to hypnotic suggestions, it is generally inferred that hypnosis has been induced. Many believe that hypnotic responses and experiences are characteristic of a hypnotic state. While some think that it is not necessary to use the word "hypnosis" as part of the hypnotic induction, others view it as essential.[70]

Michael Nash provides a list of eight definitions of hypnosis by different authors, in addition to his own view that hypnosis is "a special case of psychological regression":

- Janet, near the turn of the century, and more recently Ernest Hilgard ..., have defined hypnosis in terms of dissociation.

- Social psychologists Sarbin and Coe ... have described hypnosis in terms of role theory. Hypnosis is a role that people play; they act "as if" they were hypnotised.

- T. X. Barber ... defined hypnosis in terms of nonhypnotic behavioural parameters, such as task motivation and the act of labeling the situation as hypnosis.

- In his early writings, Weitzenhoffer ... conceptualised hypnosis as a state of enhanced suggestibility. Most recently ... he has defined hypnotism as "a form of influence by one person exerted on another through the medium or agency of suggestion."

- Psychoanalysts Gill and Brenman ... described hypnosis by using the psychoanalytic concept of "regression in the service of the ego".

- Edmonston ... has assessed hypnosis as being merely a state of relaxation.

- Spiegel and Spiegel... have implied that hypnosis is a biological capacity.[71]

- Erickson ... is considered the leading exponent of the position that hypnosis is a special, inner-directed, altered state of functioning.[71]

Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell (the originators of the human givens approach) define hypnosis as "any artificial way of accessing the REM state, the same brain state in which dreaming occurs" and suggest that this definition, when properly understood, resolves "many of the mysteries and controversies surrounding hypnosis".[72] They see the REM state as being vitally important for life itself, for programming in our instinctive knowledge initially (after Dement[73] and Jouvet[74]) and then for adding to this throughout life. They attempt to explain this by asserting that, in a sense, all learning is post-hypnotic, which they say explains why the number of ways people can be put into a hypnotic state are so varied: according to them, anything that focuses a person's attention, inward or outward, puts them into a trance.[75]

Induction

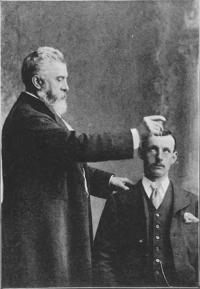

Hypnosis is normally preceded by a "hypnotic induction" technique. Traditionally, this was interpreted as a method of putting the subject into a "hypnotic trance"; however, subsequent "nonstate" theorists have viewed it differently, seeing it as a means of heightening client expectation, defining their role, focusing attention, etc. The induction techniques and methods are dependent on the depth of hypnotic trance level and for each stage of trance, the number of which in some sources ranges from 30 stages to 50 stages, there are different types of inductions.[76] There are several different induction techniques. One of the most influential methods was Braid's "eye-fixation" technique, also known as "Braidism". Many variations of the eye-fixation approach exist, including the induction used in the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS), the most widely used research tool in the field of hypnotism.[77] Braid's original description of his induction is as follows:

Take any bright object (e.g. a lancet case) between the thumb and fore and middle fingers of the left hand; hold it from about eight to fifteen inches from the eyes, at such position above the forehead as may be necessary to produce the greatest possible strain upon the eyes and eyelids, and enable the patient to maintain a steady fixed stare at the object.

The patient must be made to understand that he is to keep the eyes steadily fixed on the object, and the mind riveted on the idea of that one object. It will be observed, that owing to the consensual adjustment of the eyes, the pupils will be at first contracted: They will shortly begin to dilate, and, after they have done so to a considerable extent, and have assumed a wavy motion, if the fore and middle fingers of the right hand, extended and a little separated, are carried from the object toward the eyes, most probably the eyelids will close involuntarily, with a vibratory motion. If this is not the case, or the patient allows the eyeballs to move, desire him to begin anew, giving him to understand that he is to allow the eyelids to close when the fingers are again carried towards the eyes, but that the eyeballs must be kept fixed, in the same position, and the mind riveted to the one idea of the object held above the eyes. In general, it will be found, that the eyelids close with a vibratory motion, or become spasmodically closed.[78]

Braid later acknowledged that the hypnotic induction technique was not necessary in every case, and subsequent researchers have generally found that on average it contributes less than previously expected to the effect of hypnotic suggestions.[57] Variations and alternatives to the original hypnotic induction techniques were subsequently developed. However, this method is still considered authoritative.[citation needed] In 1941, Robert White wrote: "It can be safely stated that nine out of ten hypnotic techniques call for reclining posture, muscular relaxation, and optical fixation followed by eye closure."[79]

Suggestionedit

When James Braid first described hypnotism, he did not use the term "suggestion" but referred instead to the act of focusing the conscious mind of the subject upon a single dominant idea. Braid's main therapeutic strategy involved stimulating or reducing physiological functioning in different regions of the body. In his later works, however, Braid placed increasing emphasis upon the use of a variety of different verbal and non-verbal forms of suggestion, including the use of "waking suggestion" and self-hypnosis. Subsequently, Hippolyte Bernheim shifted the emphasis from the physical state of hypnosis on to the psychological process of verbal suggestion:

I define hypnotism as the induction of a peculiar psychical i.e., mental condition which increases the susceptibility to suggestion. Often, it is true, the hypnotic sleep that may be induced facilitates suggestion, but it is not the necessary preliminary. It is suggestion that rules hypnotism.[80]

Bernheim's conception of the primacy of verbal suggestion in hypnotism dominated the subject throughout the 20th century, leading some authorities to declare him the father of modern hypnotism.[81]

Contemporary hypnotism uses a variety of suggestion forms including direct verbal suggestions, "indirect" verbal suggestions such as requests or insinuations, metaphors and other rhetorical figures of speech, and non-verbal suggestion in the form of mental imagery, voice tonality, and physical manipulation. A distinction is commonly made between suggestions delivered "permissively" and those delivered in a more "authoritarian" manner. Harvard hypnotherapist Deirdre Barrett writes that most modern research suggestions are designed to bring about immediate responses, whereas hypnotherapeutic suggestions are usually post-hypnotic ones that are intended to trigger responses affecting behaviour for periods ranging from days to a lifetime in duration. The hypnotherapeutic ones are often repeated in multiple sessions before they achieve peak effectiveness.[82]

Conscious and unconscious mindedit

Some hypnotists view suggestion as a form of communication that is directed primarily to the subject's conscious mind,[83] whereas others view it as a means of communicating with the "unconscious" or "subconscious" mind.[83][84] These concepts were introduced into hypnotism at the end of the 19th century by Sigmund Freud and Pierre Janet. Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theory describes conscious thoughts as being at the surface of the mind and unconscious processes as being deeper in the mind.[85] Braid, Bernheim, and other Victorian pioneers of hypnotism did not refer to the unconscious mind but saw hypnotic suggestions as being addressed to the subject's conscious mind. Indeed, Braid actually defines hypnotism as focused (conscious) attention upon a dominant idea (or suggestion). Different views regarding the nature of the mind have led to different conceptions of suggestion. Hypnotists who believe that responses are mediated primarily by an "unconscious mind", like Milton Erickson, make use of indirect suggestions such as metaphors or stories whose intended meaning may be concealed from the subject's conscious mind. The concept of subliminal suggestion depends upon this view of the mind. By contrast, hypnotists who believe that responses to suggestion are primarily mediated by the conscious mind, such as Theodore Barber and Nicholas Spanos, have tended to make more use of direct verbal suggestions and instructions.[86]

Ideo-dynamic reflexedit

The first neuropsychological theory of hypnotic suggestion was introduced early by James Braid who adopted his friend and colleague William Carpenter's theory of the ideo-motor reflex response to account for the phenomenon of hypnotism. Carpenter had observed from close examination of everyday experience that, under certain circumstances, the mere idea of a muscular movement could be sufficient to produce a reflexive, or automatic, contraction or movement of the muscles involved, albeit in a very small degree. Braid extended Carpenter's theory to encompass the observation that a wide variety of bodily responses besides muscular movement can be thus affected, for example, the idea of sucking a lemon can automatically stimulate salivation, a secretory response. Braid, therefore, adopted the term "ideo-dynamic", meaning "by the power of an idea", to explain a broad range of "psycho-physiological" (mind–body) phenomena. Braid coined the term "mono-ideodynamic" to refer to the theory that hypnotism operates by concentrating attention on a single idea in order to amplify the ideo-dynamic reflex response. Variations of the basic ideo-motor, or ideo-dynamic, theory of suggestion have continued to exercise considerable influence over subsequent theories of hypnosis, including those of Clark L. Hull, Hans Eysenck, and Ernest Rossi.[83] In Victorian psychology the word "idea" encompasses any mental representation, including mental imagery, memories, etc.

Susceptibilityedit

Braid made a rough distinction between different stages of hypnosis, which he termed the first and second conscious stage of hypnotism;[87] he later replaced this with a distinction between "sub-hypnotic", "full hypnotic", and "hypnotic coma" stages.[87] Jean-Martin Charcot made a similar distinction between stages which he named somnambulism, lethargy, and catalepsy. However, Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault and Hippolyte Bernheim introduced more complex hypnotic "depth" scales based on a combination of behavioural, physiological, and subjective responses, some of which were due to direct suggestion and some of which were not. In the first few decades of the 20th century, these early clinical "depth" scales were superseded by more sophisticated "hypnotic susceptibility" scales based on experimental research. The most influential were the Davis–Husband and Friedlander–Sarbin scales developed in the 1930s. André Weitzenhoffer and Ernest R. Hilgard developed the Stanford Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility in 1959, consisting of 12 suggestion test items following a standardised hypnotic eye-fixation induction script, and this has become one of the most widely referenced research tools in the field of hypnosis. Soon after, in 1962, Ronald Shor and Emily Carota Orne developed a similar group scale called the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility (HGSHS).

Whereas the older "depth scales" tried to infer the level of "hypnotic trance" from supposed observable signs such as spontaneous amnesia, most subsequent scales have measured the degree of observed or self-evaluated responsiveness to specific suggestion tests such as direct suggestions of arm rigidity (catalepsy). The Stanford, Harvard, HIP, and most other susceptibility scales convert numbers into an assessment of a person's susceptibility as "high", "medium", or "low". Approximately 80% of the population are medium, 10% are high, and 10% are low. There is some controversy as to whether this is distributed on a "normal" bell-shaped curve or whether it is bi-modal with a small "blip" of people at the high end.[88] Hypnotisability scores are highly stable over a person's lifetime. Research by Deirdre Barrett has found that there are two distinct types of highly susceptible subjects, which she terms fantasisers and dissociaters. Fantasisers score high on absorption scales, find it easy to block out real-world stimuli without hypnosis, spend much time daydreaming, report imaginary companions as a child, and grew up with parents who encouraged imaginary play. Dissociaters often have a history of childhood abuse or other trauma, learned to escape into numbness, and to forget unpleasant events. Their association to "daydreaming" was often going blank rather than creating vividly recalled fantasies. Both score equally high on formal scales of hypnotic susceptibility.[89][90][91]

Individuals with dissociative identity disorder have the highest hypnotisability of any clinical group, followed by those with post-traumatic stress disorder.[92]

Applicationsedit

There are numerous applications for hypnosis across multiple fields of interest, including medical/psychotherapeutic uses, military uses, self-improvement, and entertainment. The American Medical Association currently has no official stance on the medical use of hypnosis.

Hypnosis has been used as a supplemental approach to cognitive behavioral therapy since as early as 1949. Hypnosis was defined in relation to classical conditioning; where the words of the therapist were the stimuli and the hypnosis would be the conditioned response. Some traditional cognitive behavioral therapy methods were based in classical conditioning. It would include inducing a relaxed state and introducing a feared stimulus. One way of inducing the relaxed state was through hypnosis.[93]

Hypnotism has also been used in forensics, sports, education, physical therapy, and rehabilitation.[94] Hypnotism has also been employed by artists for creative purposes, most notably the surrealist circle of André Breton who employed hypnosis, automatic writing, and sketches for creative purposes. Hypnotic methods have been used to re-experience drug states[95] and mystical experiences.[96][97] Self-hypnosis is popularly used to quit smoking, alleviate stress and anxiety, promote weight loss, and induce sleep hypnosis. Stage hypnosis can persuade people to perform unusual public feats.[98]

Some people have drawn analogies between certain aspects of hypnotism and areas such as crowd psychology, religious hysteria, and ritual trances in preliterate tribal cultures.[99]

Hypnotherapyedit

Hypnotherapy is a use of hypnosis in psychotherapy.[100][101] It is used by licensed physicians, psychologists, and others. Physicians and psychologists may use hypnosis to treat depression, anxiety, eating disorders, sleep disorders, compulsive gambling, phobias and post-traumatic stress,[102][103] while certified hypnotherapists who are not physicians or psychologists often treat smoking and weight management. Hypnotherapy was historically used in psychiatric and legal settings to enhance the recall of repressed or degraded memories, but this application of the technique has declined as scientific evidence accumulated that hypnotherapy can increase confidence in false memories.[104]

Hypnotherapy is viewed as a helpful adjunct by proponents, having additive effects when treating psychological disorders, such as these, along with scientifically proven cognitive therapies. The effectiveness of hypnotherapy has not yet been accurately assessed,[105] and, due to the lack of evidence indicating any level of efficiency,[106] it is regarded as a type of alternative medicine by numerous reputable medical organisations, such as the National Health Service.[107][108]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Hypnosis

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Mesmerise (song)

Hypnotized (disambiguation)

Hypnotist (disambiguation)

File:Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière.jpg

Jean-Martin Charcot

Hysteria

Salpêtrière

Marie Wittman

Joseph Babiński

Medical Subject Headings

Q8609

File:Hypnotic Séance (Richard Bergh) - Nationalmuseum - 18855.tif

Richard Bergh

File:Photographic Studies in Hypnosis, Abnormal Psychology (1938).ogv

Animal magnetism

Hypnotherapy

Stage hypnosis

Self-hypnosis

Hypnosurgery

History of hypnosis

Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism

Barber and Calverley

Deirdre Barrett

Hippolyte Bernheim

Gil Boyne

James Braid (surgeon)

John Milne Bramwell

William Joseph Bryan

Jean-Martin Charcot

Émile Coué

Dave Elman

Milton H. Erickson

James Esdaile

John Elliotson

Sigmund Freud

Erika Fromm

Ernest Hilgard

Josephine R. Hilgard

Clark L. Hull

Pierre Janet

Irving Kirsch

Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault

Franz Mesmer

Martin Theodore Orne

Charles Poyen

Morton Prince

Amand-Marie-Jacques de Chastenet, Marquis of Puységur

Andrew Salter (psychologist)

Theodore R. Sarbin

Nicholas Spanos

André Muller Weitzenhoffer

Hypnotic susceptibility

Suggestion

Age regression in therapy

Hypnotic induction

Neuro-linguistic programming

Hypnotherapy in the United Kingdom

Template:Hypnosis

Template talk:Hypnosis

Special:EditPage/Template:Hypnosis

Attention

Suggestion

Altered state of mind

Trance

Consciousness

Role theory

Attentional control

Hypnotic induction

Hypnotherapy

Stage hypnosis

Mentalism

Irritable bowel syndrome

Menopause

Smoking cessation

Pseudoscience

Quackery

Étienne Félix d'Henin de Cuvillers

Ancient Greek

Suffix

Word stem

Aorist

James Braid (surgeon)

Franz Mesmer

Animal magnetism

History of hypnosis

Avicenna

Franz Mesmer

Abbé Faria

Elliotson

James Esdaile

Wikipedia:Verifiability#Self-published sources

Meditation

Premature burial#Voluntary

Human hibernation

Dabistān-i Mazāhib

Avicenna

Franz Mesmer

Magnetic force

Louis XVI of France

Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism

Animal magnetism

Animal magnetism#"Magnetizer"

Antoine Lavoisier

Benjamin Franklin

Joseph-Ignace Guillotin

Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism#Mesmer's "cures" were never investigated

Randomized controlled trials

Blinded experiment

Abstract and concrete

File:James Braid, portrait.jpg

James Braid (surgeon)

File:Braid's "upwards and inwards squint" induction method.tif

Dugald Stewart

Scottish School of Common Sense

Physiology

File:Affections of the Mind-(Thomas Brown)-(Yeates's representation).tif

Thomas Brown (philosopher)

William Benjamin Carpenter

Michel Eugène Chevreul

John Milne Bramwell

George Miller Beard

William Thierry Preyer

Jena University

Albert Moll (German psychiatrist)

Étienne Eugène Azam

Academy of Sciences

Paul Broca

French Academy of Science

Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault

Hippolyte Bernheim

Jean-Martin Charcot

Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital

The Salpêtrière School of Hypnosis

Nancy, France

Nancy School

Hysteria

Pierre Janet

Automatic behavior

University of Paris

Collège de France

Psychotherapy

Dissociation (psychology)

Sigmund Freud

Psychoanalysis

Catharsis

Studies on Hysteria

File:Émile Coué 3.jpg

Émile Coué

Autosuggestion

Autosuggestion

Émile Coué

Charles Baudouin

Autosuggestion

Charles Baudouin

Self-help

Cognitive therapy

Behavioural psychology

Clark L. Hull

Dave Elman

Milton H. Erickson

American Society for Clinical Hypnosis

American Psychiatric Association

American Psychological Association

American Psychopathological Association

Milton H. Erickson#Ericksonian approaches

Double bind

André Muller Weitzenhoffer

Closed-eye hallucination

Irving Kirsch

Cognitive-behavioural therapy

Joseph Wolpe

Albert Ellis (psychologist)

Clark L. Hull

Ivan Pavlov

Suggestibility

Placebo

Irving Kirsch

Psychology

American Psychological Association

Regression (psychology)

Pierre Janet

Ernest Hilgard

Dissociation (psychology)

Social psychologist

Role theory

T. X. Barber

André Muller Weitzenhoffer

Psychoanalyst

Milton H. Erickson

Ivan Tyrrell

Human givens

Rapid eye movement sleep

Hypnotic induction

Hypnotic susceptibility

Wikipedia:Citation needed

Suggestion

James Braid (surgeon)

Hippolyte Bernheim

Deirdre Barrett

Unconscious mind

Subconscious

Sigmund Freud

Pierre Janet

Milton Erickson

Subliminal message

Theodore X. Barber

Nicholas Spanos

Ideomotor response

William Benjamin Carpenter

Ideo motor response

Clark L. Hull

Hans Eysenck

Hypnotic susceptibility

Jean-Martin Charcot

Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault

André Muller Weitzenhoffer

Ernest R. Hilgard

Dissociative identity disorder

Clinic

Post-traumatic stress disorder

American Medical Association

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Classical conditioning

Relaxation (psychology)

Forensics

Sports hypnosis

Physical therapy

Drug rehabilitation

André Breton

Automatic writing

Smoking cessation

Weight loss

Crowd psychology

Hypnotherapy

Wikipedia:Neutral point of view

Wikipedia:NPOV dispute

Talk:Hypnosis##

Template:POV#When to remove

Help:Maintenance template removal

Eating disorder

Sleep disorder

Problem gambling

Phobias

Post-traumatic stress disorder

False memories

Cognitive therapy

Alternative medicine

National Health Service

Hypnosis

Hypnosis

Main Page

Wikipedia:Contents

Portal:Current events

Special:Random

Wikipedia:About

Wikipedia:Contact us

Special:FundraiserRedirector?utm source=donate&utm medium=sidebar&utm campaign=C13 en.wikipedia.org&uselang=en

Help:Contents

Help:Introduction

Wikipedia:Community portal

Special:RecentChanges

Wikipedia:File upload wizard

Main Page

Special:Search

Help:Introduction

Special:MyContributions

Special:MyTalk

Hipnose

Oferswefn

تنويم مغناطيسي

Արհեստաքուն

Hipnosis

Hipnoz

هیپنوتیسم

সম্মোহন

Гіпноз

Гіпноз

Хипноза

Hipnoza

Hipnosi

Hypnóza

Hypnosis

Hypnose

Hypnose

Hüpnoos

Ύπνωση

Hipnosis

Hipnoto

Hipnosi

هیپنوتیزم

Hypnose

Hypnoaze

Hiopnóis

Hipnose

최면

Հիպնոս

सम्मोहन

Hipnoza

Hipnosis

Ipnosi

היפנוזה

ಸಂಮೋಹನ ಶಾಸ್ತ್ರ

ჰიპნოზი

Гипноз

Гипноз

Hypnosis

Hipnoze

Hipnozė

Hipnózis

Хипноза

ഹിപ്നോട്ടിസം

ايحاء

Hipnosis

စိတ်ညှို့ပညာ

Hypnose

हिप्नाेसिस्

催眠

Hypnose

Updating...x

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.