A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on the |

| Philosophy of religion |

|---|

| Philosophy of religion article index |

An ontological argument is a philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. More specifically, ontological arguments are commonly conceived a priori in regard to the organization of the universe, whereby, if such organizational structure is true, God must exist.

The first ontological argument in Western Christian tradition[i] was proposed by Saint Anselm of Canterbury in his 1078 work, Proslogion (Latin: Proslogium, lit. 'Discourse on the Existence of God'), in which he defines God as "a being than which no greater can be conceived," and argues that such a being must exist in the mind, even in that of the person who denies the existence of God.[1] From this, he suggests that if the greatest possible being exists in the mind, it must also exist in reality, because if it existed only in the mind, then an even greater being must be possible—one who exists both in mind and in reality. Therefore, this greatest possible being must exist in reality. Similarly, in the East, Avicenna's Proof of the Truthful argued that there must be a "necessary existent".[2]

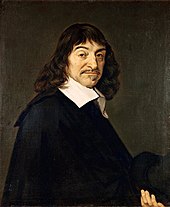

Seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes employed a similar argument to Anselm's. Descartes published several variations of his argument, each of which center on the idea that God's existence is immediately inferable from a "clear and distinct" idea of a supremely perfect being. In the early 18th century, Gottfried Leibniz augmented Descartes' ideas in an attempt to prove that a "supremely perfect" being is a coherent concept. A more recent ontological argument came from Kurt Gödel, who proposed a formal argument for God's existence. Norman Malcolm also revived the ontological argument in 1960 when he located a second, stronger ontological argument in Anselm's work; Alvin Plantinga challenged this argument and proposed an alternative, based on modal logic. Attempts have also been made to validate Anselm's proof using an automated theorem prover. Other arguments have been categorised as ontological, including those made by Islamic philosophers Mulla Sadra and Allama Tabatabai.

Just as the ontological argument has been popular, a number of criticisms and objections have also been mounted. Its first critic was Gaunilo of Marmoutiers, a contemporary of Anselm's. Gaunilo, suggesting that the ontological argument could be used to prove the existence of anything, uses the analogy of a perfect island. Such would be the first of many parodies, all of which attempted to show the absurd consequences of the ontological argument. Later, Thomas Aquinas rejected the argument on the basis that humans cannot know God's nature. David Hume also offered an empirical objection, criticising its lack of evidential reasoning and rejecting the idea that anything can exist necessarily. Immanuel Kant's critique was based on what he saw as the false premise that existence is a predicate, arguing that "existing" adds nothing (including perfection) to the essence of a being. Thus, a "supremely perfect" being can be conceived not to exist. Finally, philosophers such as C. D. Broad dismissed the coherence of a maximally great being, proposing that some attributes of greatness are incompatible with others, rendering "maximally great being" incoherent.

Contemporary defenders of the ontological argument include Alvin Plantinga, Yujin Nagasawa, and Robert Maydole.

Classification

The traditional definition of an ontological argument was given by Immanuel Kant.[3] He contrasted the ontological argument (literally any argument "concerned with being")[4] with the cosmological and physio-theoretical arguments.[5] According to the Kantian view, ontological arguments are those founded through a priori reasoning.[3]

Graham Oppy, who elsewhere expressed that he "see no urgent reason" to depart from the traditional definition,[3] defined ontological arguments as those which begin with "nothing but analytic, a priori and necessary premises" and conclude that God exists. Oppy admits, however, that not all of the "traditional characteristics" of an ontological argument (i.e. analyticity, necessity, and a priority) are found in all ontological arguments[1] and, in his 2007 work Ontological Arguments and Belief in God, suggested that a better definition of an ontological argument would employ only considerations "entirely internal to the theistic worldview."[3]

Oppy subclassified ontological arguments, based on the qualities of their premises, using the following qualities:[1][3]

- definitional: arguments that invoke definitions.

- conceptual (or hyperintensional): arguments that invoke "the possession of certain kinds of ideas or concepts."

- modal: arguments that consider possibilities.

- meinongian: arguments that assert "a distinction between different categories of existence."

- experiential: arguments that employ the idea of God existing solely to those who have had experience of him.

- mereological: arguments that "draw on…the theory of the whole-part relation."[6]

- higher-order: arguments that observe "that any collection of properties, that (a) does not include all properties and (b) is closed under entailment, is possibly jointly instantiated."

- Hegelian: the arguments of Hegel.

William Lane Craig criticised Oppy's study as too vague for useful classification. Craig argues that an argument can be classified as ontological if it attempts to deduce the existence of God, along with other necessary truths, from his definition. He suggests that proponents of ontological arguments would claim that, if one fully understood the concept of God, one must accept his existence.[7]

William L. Rowe defines ontological arguments as those which start from the definition of God and, using only a priori principles, conclude with God's existence.[8]

Development

Although a version of the ontological argument appears explicitly in the writings of the ancient Greek philosopher Xenophanes and variations appear in writings by Parmenides, Plato, and the Neoplatonists,[9] the mainstream view is that the ontological argument was first clearly stated and developed by Anselm of Canterbury.[1][10][11] Some scholars argue that Islamic philosopher Avicenna (Ibn Sina) developed a special kind of ontological argument before Anselm,[12][13] while others have doubted this position.[14][15][16]

Daniel Dombrowski marked three major stages in the development of the argument:[17]

- Anselm's initial explicit formulation,

- the 18th-century criticisms of Kant and Hume, and

- the identification of a second ontological argument in Anselm's Proslogion by 20th-century philosophers.

Anselm

Theologian and philosopher Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) proposed an ontological argument in the 2nd and 3rd chapters of his Proslogion.[18] Anselm's argument was not presented in order to prove God's existence; rather, Proslogion was a work of meditation in which he documented how the idea of God became self-evident to him.[19]

In Chapter 2 of the Proslogion, Anselm defines God as a "being than which no greater can be conceived."[1] While Anselm has often been credited as the first to understand God as the greatest possible being, this perception was actually widely described among ancient Greek philosophers and early Christian writers.[20][21] He suggests that even "the fool" can understand this concept, and this understanding itself means that the being must exist in the mind. The concept must exist either only in our mind, or in both our mind and in reality. If such a being exists only in our mind, then a greater being—that which exists in the mind and in reality—can be conceived (this argument is generally regarded as a reductio ad absurdum because the view of the fool is proven to be inconsistent). Therefore, if we can conceive of a being than which nothing greater can be conceived, it must exist in reality. Thus, a being than which nothing greater could be conceived, which Anselm defined as God, must exist in reality.[22]

Anselm's argument in Chapter 2 can be summarized as follows:[23]

- It is a conceptual truth (or, so to speak, true by definition) that God is a being than which none greater can be imagined (that is, the greatest possible being that can be imagined).

- God exists as an idea in the mind.

- A being that exists as an idea in the mind and in reality is, other things being equal, greater than a being that exists only as an idea in the mind.

- Thus, if God exists only as an idea in the mind, then we can imagine something that is greater than God (that is, a greatest possible being that does exist).

- But we cannot imagine something that is greater than God (for it is a contradiction to suppose that we can imagine a being greater than the greatest possible being that can be imagined.)

- Therefore, God exists.

In Chapter 3, Anselm presents a further argument in the same vein:[23]

- By definition, God is a being than which none greater can be imagined.

- A being that necessarily exists in reality is greater than a being that does not necessarily exist.

- Thus, by definition, if God exists as an idea in the mind but does not necessarily exist in reality, then we can imagine something that is greater than God.

- But we cannot imagine something that is greater than God.

- Thus, if God exists in the mind as an idea, then God necessarily exists in reality.

- God exists in the mind as an idea.

- Therefore, God necessarily exists in reality.

This contains the notion of a being that cannot be conceived not to exist. He argued that if something can be conceived not to exist, then something greater can be conceived. Consequently, a thing than which nothing greater can be conceived cannot be conceived not to exist and so it must exist. This can be read as a restatement of the argument in Chapter 2, although Norman Malcolm believes it to be a different, stronger argument.[24]

René Descartes

René Descartes (1596–1650) proposed a number of ontological arguments that differ from Anselm's formulation. Generally speaking, they are less formal arguments than they are natural intuition.

In Meditation, Book V, Descartes wrote:[25]

But, if the mere fact that I can produce from my thought the idea of something entails that everything that I clearly and distinctly perceive to belong to that thing really does belong to it, is not this a possible basis for another argument to prove the existence of God? Certainly, the idea of God, or a supremely perfect being, is one that I find within me just as surely as the idea of any shape or number. And my understanding that it belongs to his nature that he always exists is no less clear and distinct than is the case when I prove of any shape or number that some property belongs to its nature.

Descartes argues that God's existence can be deduced from his nature, just as geometric ideas can be deduced from the nature of shapes—he used the deduction of the sizes of angles in a triangle as an example. He suggested that the concept of God is that of a supremely perfect being, holding all perfections. He seems to have assumed that existence is a predicate of a perfection. Thus, if the notion of God did not include existence, it would not be supremely perfect, as it would be lacking a perfection. Consequently, the notion of a supremely perfect God who does not exist, Descartes argues, is unintelligible. Therefore, according to his nature, God must exist.[26]

Baruch Spinoza

In Spinoza's Short Treatise on God, Man, and His Well-Being, he wrote a section titled "Treating of God and What Pertains to Him", in which he discusses God's existence and what God is. He starts off by saying: "whether there is a God, this, we say, can be proved".[27] His proof for God follows a similar structure as Descartes' ontological argument. Descartes attempts to prove God's existence by arguing that there "must be some one thing that is supremely good, through which all good things have their goodness".[28] Spinoza's argument differs in that he does not move straight from the conceivability of the greatest being to the existence of God, but rather uses a deductive argument from the idea of God. Spinoza says that man's ideas do not come from himself, but from some sort of external cause. Thus the things whose characteristics a man knows must have come from some prior source. So, if man has the idea of God, then God must exist before this thought, because man cannot create an idea of his own imagination.[27]

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz saw a problem with Descartes' ontological argument: that Descartes had not asserted the coherence of a "supremely perfect" being. He proposed that, unless the coherence of a supremely perfect being could be demonstrated, the ontological argument fails. Leibniz saw perfection as impossible to analyse; therefore, it would be impossible to demonstrate that all perfections are incompatible. He reasoned that all perfections can exist together in a single entity, and that Descartes' argument is still valid.[29]

Mulla Sadra

Mulla Sadra (c. 1571/2 – 1640) was an Iranian Shia Islamic philosopher who was influenced by earlier Muslim philosophers such as Avicenna and Suhrawardi, as well as the Sufi metaphysician Ibn 'Arabi. Sadra discussed Avicenna's arguments for the existence of God, claiming that they were not a priori. He rejected the argument on the basis that existence precedes essence, or that the existence of human beings is more fundamental than their essence.[30]

Sadra put forward a new argument, known as Seddiqin Argument or Argument of the Righteous. The argument attempts to prove the existence of God through the reality of existence, and to conclude with God's pre-eternal necessity. In this argument, a thing is demonstrated through itself, and a path is identical with the goal. In other arguments, the truth is attained from an external source, such as from the possible to the necessary, from the originated to the eternal origin, or from motion to the unmoved mover. In the argument of the righteous, there is no middle term other than the truth.[31] His version of the ontological argument can be summarized as follows:[30]

- There is existence

- Existence is a perfection above which no perfection may be conceived

- God is perfection and perfection in existence

- Existence is a singular and simple reality; there is no metaphysical pluralism

- That singular reality is graded in intensity in a scale of perfection (that is, a denial of a pure monism).

- That scale must have a limit point, a point of greatest intensity and of greatest existence.

- Hence God exists.

Mulla Sadra describes this argument in his main work al-asfar al-arba‘a as follows:

Existence is a single, objective and simple reality, and there is no difference between its parts, unless in terms of perfection and imperfection, strength, and weakness... And the culmination of its perfection, where there is nothing more perfect, is its independence from any other thing. Nothing more perfect should be conceivable, as every imperfect thing belongs to another thing and needs this other to become perfect. And, as it has already been explicated, perfection is prior to imperfection, actuality to potency, and existence to non-existence. Also, it has been explained that the perfection of a thing is the thing itself, and not a thing in addition to it. Thus, either existence is independent of others or it is in need of others. The former is the Necessary, which is pure existence. Nothing is more perfect than Him. And in Him there is no room for non-existence or imperfection. The latter is other than Him, and is regarded as His acts and effects, and for other than Him there is no subsistence, unless through Him. For there is no imperfection in the reality of existence, and imperfection is added to existence only because of the quality of being caused, as it is impossible for an effect to be identical with its cause in terms of existence.[32]

G. W. F. Hegel

In response to Kant's rejection of traditional speculative philosophy in his First Critique, and to Kant's rejection of the Ontological Argument, G. W. F. Hegel proposed throughout his lifetime works that Immanuel Kant was mistaken. Hegel took aim at Kant's famous $100 argument. Kant had said that "it is one thing to have $100 in my mind, and quite a different thing to have $100 in my pocket." According to Kant, we can imagine a God, but that doesn't prove that God exists.

Hegel argued that Kant's formulation was inaccurate. Hegel referred to Kant's error in all of his major works from 1807 to 1831. For Hegel, "The True is the Whole" (PhG, para. 20). For Hegel, the True is the Geist which is to say, Spirit, which is to say, God. Thus God is the Whole of the Cosmos, both unseen as well as seen. This error of Kant, therefore, was his comparison of a finite (contingent) entity such as $100, with Infinite (necessary) Being, i.e. the Whole.

When regarded as the Whole of Being, unseen as well as seen, and not simply "one being among many," then the Ontological Argument flourishes, and its logical necessity become obvious, according to Hegel.

The final book contract that Hegel signed in the year that he died, 1831, was for a book entitled, Lectures on the Proofs of the Existence of God. Hegel died before finishing the book. It was to have three sections: (1) The Cosmological Argument; (2) The Teleological Argument; and (3) the Ontological Argument. Hegel died before beginning sections 2 and 3. His work is published today as incomplete, with only part of his Cosmological Argument intact.

To peruse Hegel's ideas on the Ontological Argument, scholars have had to piece together his arguments from various paragraphs from his other works. Certain scholars have suggested that all of Hegel's philosophy composes an ontological argument.[33][34]

Kurt Gödel

Mathematician Kurt Gödel provided a formal argument for God's existence. The argument was constructed by Gödel but not published until long after his death. He provided an argument based on modal logic; he uses the conception of properties, ultimately concluding with God's existence.[35]

Definition 1: x is God-like if and only if x has as essential properties those and only those properties which are positive

Definition 2: A is an essence of x if and only if for every property B, x has B necessarily if and only if A entails B

Definition 3: x necessarily exists if and only if every essence of x is necessarily exemplified

Axiom 1: If a property is positive, then its negation is not positive

Axiom 2: Any property entailed by—i.e., strictly implied by—a positive property is positive

Axiom 3: The property of being God-like is positive

Axiom 4: If a property is positive, then it is necessarily positive

Axiom 5: Necessary existence is positive

Axiom 6: For any property P, if P is positive, then being necessarily P is positive

Theorem 1: If a property is positive, then it is consistent, i.e., possibly exemplified

Corollary 1: The property of being God-like is consistent

Theorem 2: If something is God-like, then the property of being God-like is an essence of that thing

Theorem 3: Necessarily, the property of being God-like is exemplified

Gödel defined being "god-like" as having every positive property. He left the term "positive" undefined. Gödel proposed that it is understood in an aesthetic and moral sense, or alternatively as the opposite of privation (the absence of necessary qualities in the universe). He warned against interpreting "positive" as being morally or aesthetically "good" (the greatest advantage and least disadvantage), as this includes negative characteristics. Instead, he suggested that "positive" should be interpreted as being perfect, or "purely good", without negative characteristics.[36]

Gödel's listed theorems follow from the axioms, so most criticisms of the theory focus on those axioms or the assumptions made. For instance, axiom 5 does not explain why necessary existence is positive instead of possible existence, an axiom which the whole argument follows from. Or, for Axiom 1, to use another example, the negation of a positive property both includes the lack of any properties and the opposite property, and only the lack of any properties is a privation of a property, not the opposite property (for instance, the lack of happiness can symbolize either sadness or having no emotion, but only lacking emotion could be seen as a privation, or negative property). Either of these axioms being seen as not mapping to reality would cause the whole argument to fail. Oppy argued that Gödel gives no definition of "positive properties". He suggested that if these positive properties form a set, there is no reason to believe that any such set exists which is theologically interesting, or that there is only one set of positive properties which is theologically interesting.[35]

Modal versions of the ontological argument

Modal logic deals with the logic of possibility as well as necessity. Paul Oppenheimer and Edward N. Zalta note that, for Anselm's Proslogion chapter 2, "Many recent authors have interpreted this argument as a modal one." In the phrase 'that than which none greater can be conceived', the word 'can' could be construed as referring to a possibility. Nevertheless, the authors write that "the logic of the ontological argument itself doesn't include inferences based on this modality."[37] However, there have been newer, avowedly modal logic versions of the ontological argument, and on the application of this type of logic to the argument, James Franklin Harris writes:

ifferent versions of the ontological argument, the so-called "modal" versions of the argument, which arguably avoid the part of Anselm's argument that "treats existence as a predicate," began to emerge. The of these forms of defense of the ontological argument has been the most significant development.[38]

Hartshorne and Malcolm

Charles Hartshorne and Norman Malcolm are primarily responsible for introducing modal versions of the argument into the contemporary debate. Both claimed that Anselm had two versions of the ontological argument, the second of which was a modal logic version. According to James Harris, this version is represented by Malcolm thus:

If it can be conceived at all it must exist. For no one who denies or doubts the existence of a being a greater than which is inconceivable, denies or doubts that if it did exist its nonexistence, either in reality or in the understanding, would be impossible. For otherwise it would not be a being a greater than which cannot be conceived. But as to whatever can be conceived but does not exist: if it were to exist its nonexistence either in reality or in the understanding would be possible. Therefore, if a being a greater than which cannot be conceived, can even be conceived, it must exist.

Hartshorne says that, for Anselm, "necessary existence is a superior manner of existence to ordinary, contingent existence and that ordinary, contingent existence is a defect." For Hartshorne, both Hume and Kant focused only upon whether what exists is greater than what does not exist. However, "Anselm's point is that what exists and cannot not exist is greater than that which exists and can not exist." This avoids the question of whether or not existence is a predicate.[38]

Referring to the two ontological arguments proposed by Anselm in Chapters 2 and 3 of his Proslogion, Malcolm supported Kant's criticism of Anselm's argument in Chapter 2: that existence cannot be a perfection of something. However, he identified what he sees as the second ontological argument in Chapter 3 which is not susceptible to such criticism.[39]

In Anselm's second argument, Malcolm identified two key points: first, that a being whose non-existence is logically impossible is greater than a being whose non-existence is logically possible, and second, that God is a being "than which a greater cannot be conceived". Malcolm supported that definition of God and suggested that it makes the proposition of God's existence a logically necessarily true statement (in the same way that "a square has four sides" is logically necessarily true).[39] Thus, while rejecting the idea of existence itself being a perfection, Malcolm argued that necessary existence is a perfection. This, he argued, proved the existence of an unsurpassably great necessary being.

Jordan Sobel writes that Malcolm is incorrect in assuming that the argument he is expounding is to be found entirely in Proslogion chapter 3. "Anselm intended in Proslogion III not an independent argument for the existence of God, but a continuation of the argument of Proslogion II."[40]

Alvin Plantinga

Christian Analytic philosopher Alvin Plantinga[41] criticized Malcolm's and Hartshorne's arguments, and offered an alternative.

Plantinga developed his argument in the books titled The nature of necessity (1974; ch. 10) and God, Freedom and Evil (1975; part 2 c).[42] He argued that, if Malcolm does prove the necessary existence of the greatest possible being, it follows that there is a being which exists in all worlds whose greatness in some worlds is not surpassed. It does not, he argued, demonstrate that such a being has unsurpassed greatness in this actual world.[43]

In an attempt to resolve this problem, Plantinga differentiated between "greatness" and "excellence". A being's excellence in a particular world depends only on its properties in that world; a being's greatness depends on its properties in all worlds. Therefore, the greatest possible being must have maximal excellence in every possible world. Plantinga then restated Malcolm's argument, using the concept of "maximal greatness". He argued that it is possible for a being with maximal greatness to exist, so a being with maximal greatness exists in a possible world. If this is the case, then a being with maximal greatness exists in every world, and therefore in this world.[43]

The conclusion relies on a form of modal axiom 5 of S5, which states that if something is possibly true, then its possibility is necessary (it is possibly true in all worlds; in symbols: ). Plantinga's version of S5 suggests that "To say that p is possibly necessarily true is to say that, with regard to one possible world, it is true at all worlds; but in that case it is true at all worlds, and so it is simply necessary."[44] In other words, to say that p is necessarily possible means that p is true in at least one possible world W (if it is an actual world; Plantinga also used Axioms B of S5: ) and thus it is true in all worlds because its omnipotence, omniscience, and moral perfection are its essence.

In the 1975 version of the argument, Plantinga clarified that[42] "it follows that if W had been actual, it would have been impossible that there be no such being. That is, if W had been actual,

- (33) There is no omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect being,

would have been an impossible proposition. But if a proposition is impossible in at least one possible world, then it is impossible in every possible world; what is impossible does not vary from world to world. Accordingly (33) is impossible in the actual world, i.e., impossible simpliciter. But if it is impossible that there be no such being, then there actually exists a being that is omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect; this being, furthermore, has these qualities essentially and exists in every possible world."

A version of his argument may be formulated as follows:[29]

- A being has maximal excellence in a given possible world W if and only if it is omnipotent, omniscient and wholly good in W; and

- A being has maximal greatness if it has maximal excellence in every possible world.

- It is possible that there is a being that has maximal greatness. (Premise)

- Therefore, possibly, it is necessarily true that an omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly good being exists.

- Therefore, (by axiom 5 of S5) it is necessarily true that an omniscient, omnipotent and perfectly good being exists.

- Therefore, an omniscient, omnipotent and perfectly good being exists.

Plantinga argued that, although the first premise is not rationally established, it is not contrary to reason. Michael Martin argued that, if certain components of perfection are contradictory, such as omnipotence and omniscience, then the first premise is contrary to reason. Martin also proposed parodies of the argument, suggesting that the existence of anything can be demonstrated with Plantinga's argument, provided it is defined as perfect or special in every possible world.[45]

Another Christian philosopher, William Lane Craig, characterizes Plantinga's argument in a slightly different way:

- It is possible that a maximally great being exists.

- If it is possible that a maximally great being exists, then a maximally great being exists in some possible world.

- If a maximally great being exists in some possible world, then it exists in every possible world.

- If a maximally great being exists in every possible world, then it exists in the actual world.

- If a maximally great being exists in the actual world, then a maximally great being exists.

- Therefore, a maximally great being exists.

According to Craig, premises (2)–(5) are relatively uncontroversial among philosophers, but "the epistemic entertainability of premise (1) (or its denial) does not guarantee its metaphysical possibility."[46] Furthermore the philosopher Richard M. Gale argued that premise three, the "possibility premise", begs the question. He stated that one only has the epistemic right to accept the premise if one understands the nested modal operators, and that if one understands them within the system S5—without which the argument fails—then one understands that "possibly necessarily" is in essence the same as "necessarily".[47] Thus the premise begs the question because the conclusion is embedded within it. On S5 systems in general, James Garson writes that "the words ‘necessarily’ and ‘possibly’, have many different uses. So the acceptability of axioms for modal logic depends on which of these uses we have in mind."[48]

Sankara's dictum

An approach to supporting the possibility premise in Plantinga's version of the argument was attempted by Alexander Pruss. He started with the 8th–9th-century AD Indian philosopher Sankara's dictum that if something is impossible, we cannot have a perception (even a non-veridical one) that it is the case. It follows that if we have a perception that p, then even though it might not be the case that p, it is at least the case that possibly p. If mystics in fact perceive the existence of a maximally great being, it follows that the existence of a maximally great being is at least possible.[49]

Automated reasoning

Paul Oppenheimer and Edward N. Zalta used an automated theorem prover—Prover9—to validate Anselm's ontological thesis. Prover9 subsequently discovered a simpler, formally valid (if not necessarily sound) ontological argument from a single non-logical premise.[50]

Christoph Benzmuller and Bruno Woltzenlogel Paleo used an automated theorem prover to validate Scott's version of Gödel's ontological argument. It has been shown by the same researchers that Gödel's ontological argument is inconsistent. However, Scott's version of Gödel's ontological argument is consistent and thus valid.

Other formulations

The novelist and philosopher Iris Murdoch formulated a version of the ontological argument in her book Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals. Though she believed her version of the argument to be superior, she did reserve praise for Descartes' formulation. Her argument was phrased by her in the following way:

There is no plausible 'proof' of the existence of God except some form of the ontological proof, a 'proof' incidentally which must now take on an increased importance in theology as a result of the recent 'de-mythologising'. If considered carefully, however, the ontological proof is seen to be not exactly a proof but rather a clear assertion of faith (it is often admitted to be appropriate only for those already convinced), which could only be confidently be made on a certain amount of experience. This assertion could be put in various ways. The desire for God is certain to receive a response. My conception of God contains the certainty of its own reality. God is an object of love which uniquely excludes doubt and relativism. Such obscure statements would of course receive little sympathy from analytical philosophers, who would divide their content between psychological fact and metaphysical nonsense.[51]

In other words, atheists may feel objections to such an argument purely on the basis that they rely on a priori methodology. Her formulations rely upon the human connections of God and man, and what such a faith does to people.

Meta-logical approach

The italian journalist Thomas Emilio Villa argues that if we define God as an entity "than which no greater can be conceived", then still would be under a bigger idea, the ones of existence or non-existence. If God is God, must be a greater idea than the one of existence or non-existence. It is beyond it, otherwise the bigger idea is not "God" but the idea of "existence" itself. If God is God, then must be beyond the ideas of existence and non-existence. It must be a meta-existing being. Therefore the question whether God exist or do not exist is a non-sense: by definition, the idea of God must be beyond existence or its status would not the one of a proper God.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Ontological_argument

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.