A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

A Persian carpet (Persian: فرش ایرانی, romanized: farš-e irâni ) or Persian rug (Persian: قالی ایرانی, romanized: qâli-ye irâni ),[1] also known as Iranian carpet, is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in Iran (historically known as Persia), for home use, local sale, and export. Carpet weaving is an essential part of Persian culture and Iranian art. Within the group of Oriental rugs produced by the countries of the "rug belt", the Persian carpet stands out by the variety and elaborateness of its manifold designs.

Persian rugs and carpets of various types were woven in parallel by nomadic tribes in village and town workshops, and by royal court manufactories alike. As such, they represent miscellaneous, simultaneous lines of tradition, and reflect the history of Iran, Persian culture, and its various peoples. The carpets woven in the Safavid court manufactories of Isfahan during the sixteenth century are famous for their elaborate colors and artistical design, and are treasured in museums and private collections all over the world today. Their patterns and designs have set an artistic tradition for court manufactories which was kept alive during the entire duration of the Persian Empire up to the last royal dynasty of Iran.

Carpets woven in towns and regional centers like Tabriz, Kerman, Ravar, Neyshabour, Mashhad, Kashan, Isfahan, Nain and Qom are characterized by their specific weaving techniques and use of high-quality materials, colours and patterns. Town manufactories like those of Tabriz have played an important historical role in reviving the tradition of carpet weaving after periods of decline. Rugs woven by the villages and various tribes of Iran are distinguished by their fine wool, bright and elaborate colours, and specific, traditional patterns. Nomadic and small village weavers often produce rugs with bolder and sometimes more coarse designs, which are considered as the most authentic and traditional rugs of Persia, as opposed to the artistic, pre-planned designs of the larger workplaces. Gabbeh rugs are the best-known type of carpet from this line of tradition.

As a result of political unrest or commercial pressure, carpet weaving has gone through periods of decline throughout the decades. It particularly suffered from the introduction of synthetic dyes during the second half of the nineteenth century. Carpet weaving still plays a critical role in the economy of modern Iran. Modern production is characterized by the revival of traditional dyeing with natural dyes, the reintroduction of traditional tribal patterns, but also by the invention of modern and innovative designs, woven in the centuries-old technique. Hand-woven Persian rugs and carpets have been regarded as objects of high artistic and utilitarian value and prestige since the first time they were mentioned by ancient Greek writers.

Although the term "Persian carpet" most often refers to pile-woven textiles, flat-woven carpets and rugs like Kilim, Soumak, and embroidered tissues like Suzani are part of the rich and manifold tradition of Persian carpet weaving.

In 2010, the "traditional skills of carpet weaving" in Fars Province and Kashan were inscribed to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[2][3]

History

The beginning of carpet weaving remains unknown, as carpets are subject to use, deterioration, and destruction by insects and rodents. Woven rugs probably developed from earlier floor coverings, made of felt, or a technique known as "flat weaving".[4] Flat-woven rugs are made by tightly interweaving the warp and weft strands of the weave to produce a flat surface with no pile. The technique of weaving carpets further developed into a technique known as loop weaving. Loop weaving is done by pulling the weft strings over a gauge rod, creating loops of thread facing the weaver. The rod is then either removed, leaving the loops closed, or the loops are cut over the protecting rod, resulting in a rug very similar to a genuine pile rug. Hand-woven pile rugs are produced by knotting strings of thread individually into the warps, cutting the thread after each single knot.

The Pazyryk carpet: Earliest pile-woven carpet

The Pazyryk carpet was excavated in 1949 from the grave of a Scythian nobleman in the Pazyryk Valley of the Altai Mountains in Siberia. Radiocarbon testing indicated that the Pazyryk carpet was woven in the 5th century BC.[5] This carpet is 183 by 200 centimetres (72 by 79 inches) and has 36 symmetrical knots per cm2 (232 per inch2).[6] The advanced technique used in the Pazyryk carpet indicates a long history of evolution and experience in weaving. It is considered the oldest known carpet in the world.[7] Its central field is a deep red color and it has two animal frieze borders proceeding in opposite directions accompanied by guard stripes. The inner main border depicts a procession of deer, the outer men on horses, and men leading horses. The horse saddlecloths are woven in different designs. The inner field contains 4 × 6 identical square frames arranged in rows on a red ground, each filled by identical, star-shaped ornaments made up by centrally overlapping x- and cross-shaped patterns. The design of the carpet already shows the basic arrangement of what was to become the standard oriental carpet design: A field with repeating patterns, framed by a main border in elaborate design, and several secondary borders.[citation needed]

The discoverer of the Pazyryk carpet, Sergei Rudenko, assumed it to be a product of the contemporary Achaemenids.[8][9] Whether it was produced in the region where it was found, or is a product of Achaemenid manufacture, remains subject to debate.[10][11] Its fine weaving and elaborate pictorial design hint at an advanced state of the art of carpet weaving at the time of its production.

Early fragments

There are documentary records of carpets being used by the ancient Greeks. Homer, assumed to have lived around 850 BC, writes in Ilias XVII,350 that the body of Patroklos is covered with a "splendid carpet". In Odyssey Book VII and X "carpets" are mentioned. Pliny the Elder wrote (nat. VIII, 48) that carpets ("polymita") were invented in Alexandria. It is unknown whether these were flatweaves or pile weaves, as no detailed technical information is provided in the Greek and Latin texts.

Flat-woven kilims dating to at least the fourth or fifth century AD were found in Turfan, Hotan prefecture, East Turkestan, China, an area which still produces carpets today. Rug fragments were also found in the Lop Nur area, and are woven in symmetrical knots, with 5-7 interwoven wefts after each row of knots, with a striped design, and various colours. They are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.[12] Other fragments woven in symmetrical as well as asymmetrical knots have been found in Dura-Europos in Syria,[13] and from the At-Tar caves in Iraq,[14] dated to the first centuries AD.

These rare findings demonstrate that all the skills and techniques of dyeing and carpet weaving were already known in western Asia before the first century AD.

Early history: circa 500 BC – 200 AD

Persian carpets were first mentioned around 400 BC, by the Greek author Xenophon in his book "Anabasis":

"αὖθις δὲ Τιμασίωνι τῷ Δαρδανεῖ προσελθών, ἐπεὶ ἤκουσεν αὐτῷ εἶναι καὶ ἐκπώματα καὶ τάπιδας βαρβαρικάς", (Xen. anab. VII.3.18)

- Next he went to Timasion the Dardanian, for he heard that he had some Persian drinking cups and carpets.

"καὶ Τιμασίων προπίνων ἐδωρήσατο φιάλην τε ἀργυρᾶν καὶ τάπιδα ἀξίαν δέκα μνῶν."

- Timasion also drank his health and presented him with a silver bowl and a carpet worth ten mines.[15]

Xenophon describes Persian carpets as precious, and worthy to be used as diplomatic gifts. It is unknown if these carpets were pile-woven, or produced by another technique, e.g., flat-weaving, or embroidery, but it is interesting that the very first reference to Persian carpets in the world literature already puts them into a context of luxury, prestige, and diplomacy.

There are no surviving Persian carpets from the reigns of the Achaemenian (553–330 BC), Seleucid (312–129 BC), and Parthian (ca. 170 BC – 226 AD) kings.

The Sasanian Empire: 224–651

The Sasanian Empire, which succeeded the Parthian Empire, was recognized as one of the leading powers of its time, alongside its neighbouring Byzantine Empire, for a period of more than 400 years.[16] The Sasanids established their empire roughly within the borders set by the Achaemenids, with the capital at Ctesiphon. This last Persian dynasty before the arrival of Islam adopted Zoroastrianism as the state religion.

When and how exactly the Persians started weaving pile carpets is currently unknown, but the knowledge of carpet weaving, and of suitable designs for floor coverings, was certainly available in the area covering Byzance, Anatolia, and Persia: Anatolia, located between Byzance and Persia, was ruled by the Roman Empire since 133 BCE. Geographically and politically, by changing alliances and warfare as well as by trade, Anatolia connected the East Roman with the Persian Empire. Artistically, both empires have developed similar styles and decorative vocabulary, as exemplified by mosaics and architecture of Roman Antioch.[17] A Turkish carpet pattern depicted on Jan van Eyck's "Paele Madonna" painting was traced back to late Roman origins and related to early Islamic floor mosaics found in the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.[18]

Flat weaving and embroidery were known during the Sasanian period. Elaborate Sasanian silk textiles were well preserved in European churches, where they were used as coverings for relics, and survived in church treasuries.[19] More of these textiles were preserved in Tibetan monasteries, and were removed by monks fleeing to Nepal during the Chinese cultural revolution, or excavated from burial sites like Astana, on the Silk Road near Turfan. The high artistic level reached by Persian weavers is further exemplified by the report of the historian Al-Tabari about the Spring of Khosrow carpet, taken as booty by the Arabian conquerors of Ctesiphon in 637 AD. The description of the rug's design by al-Tabari makes it seem unlikely that the carpet was pile woven.[20][21]

Fragments of pile rugs from findspots in north-eastern Afghanistan, reportedly originating from the province of Samangan, have been carbon-14 dated to a time span from the turn of the second century to the early Sasanian period. Among these fragments, some show depictions of animals, like various stags (sometimes arranged in a procession, recalling the design of the Pazyryk carpet) or a winged mythical creature. Wool is used for warp, weft, and pile, the yarn is crudely spun, and the fragments are woven with the asymmetric knot associated with Persian and far-eastern carpets. Every three to five rows, pieces of unspun wool, strips of cloth and leather are woven in.[22] These fragments are now in the Al-Sabah Collection in the Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Kuwait.[23]

The carpet fragments, although reliably dated to the early Sasanian time, do not seem to be related to the splendid court carpets described by the Arab conquerors. Their crude knots incorporating shag on the reverse hints at the need for increased insulation. With their coarsely finished animal and hunting depictions, these carpets were likely woven by nomadic people.[24]

The advent of Islam and the Caliphates: 651–1258

The Muslim conquest of Persia led to the end of the Sasanian Empire in 651 and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. Persia became a part of the Islamic world, ruled by Muslim Caliphates.

Arabian geographers and historians visiting Persia provide, for the first time, references to the use of carpets on the floor. The unknown author of the Hudud al-'Alam states that rugs were woven in Fārs. 100 years later, Al-Muqaddasi refers to carpets in the Qaināt. Yaqut al-Hamawi tells us that carpets were woven in Azerbaijān in the thirteenth century. The great Arabian traveller Ibn Battuta mentions that a green rug was spread before him when he visited the winter quarter of the Bakhthiari atabeg in Idhej. These references indicate that carpet weaving in Persia under the Caliphate was a tribal or rural industry.[25]

The rule of the Caliphs over Persia ended when the Abbasid Caliphate was overthrown in the Siege of Baghdad (1258) by the Mongol Empire under Hulagu Khan. The Abbasid line of rulers recentered themselves in the Mamluk capital of Cairo in 1261. Though lacking in political power, the dynasty continued to claim authority in religious matters until after the Ottoman conquest of Egypt (1517). Under the Mamluk dynasty in Cairo, large carpets known as "Mamluk carpets" were produced.[26]

Seljuq invasion and Turko-Persian tradition: 1040–1118

Beginning at latest with the Seljuq invasions of Anatolia and northwestern Persia, a distinct Turko-Persian tradition emerged. Fragments of woven carpets were found in the Alâeddin Mosque in the Turkish town of Konya and the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir, and were dated to the Anatolian Seljuq Period (1243–1302).[27][28] More fragments were found in Fostat, today a suburb of the city of Cairo.[29] These fragments at least give us an idea how Seluq carpets may have looked. The Egyptian findings also provide evidence for export trade. If, and how, these carpets influenced Persian carpet weaving, remains unknown, as no distinct Persian carpets are known to exist from this period, or we are unable to identify them. It was assumed by Western scholars that the Sejuqs may have introduced at least new design traditions, if not the craft of pile weaving itself, to Persia, where skilled artisans and craftsmen might have integrated new ideas into their old traditions.[20]

Carpet fragment from Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beysehir, Turkey. Seljuq Period, 13th century.

Seljuq carpet, 320 by 240 centimetres (126 by 94 inches), from the Alâeddin Mosque, Konya, 13th century

The Mongol Ilkhanate (1256–1335) and Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

Between 1219 and 1221, Persia was raided by the Mongols. After 1260, the title "Ilkhan" was borne by the descendants of Hulagu Khan and later other Borjigin princes in Persia. At the end of the thirteenth century, Ghazan Khan built a new capital at Shãm, near Tabriz. He ordered the floors of his residence to be covered with carpets from Fārs.[25]

With the death of Ilkhan Abu Said Bahatur in 1335, Mongol rule faltered and Persia fell into political anarchy. In 1381, Timur invaded Iran and became the founder of the Timurid Empire. His successors, the Timurids, maintained a hold on most of Iran until they had to submit to the "White Sheep" Turkmen confederation under Uzun Hassan in 1468; Uzun Hasan and his successors were the masters of Iran until the rise of the Safavids.

In 1463, the Venetian Senate, seeking allies in the Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–1479) established diplomatic relations with Uzun Hassans court at Tabriz. In 1473, Giosafat Barbaro was sent to Tabriz. In his reports to the Senate of Venetia he mentions more than once the splendid carpets which he saw at the palace. Some of them, he wrote, were of silk.[30]

In 1403-05 Ruy González de Clavijo was the ambassador of Henry III of Castile to the court of Timur, founder and ruler of the Timurid Empire. He described that in Timur's palace at Samarkand, "everywhere the floor was covered with carpets and reed mattings".[31] Timurid period miniatures show carpets with geometrical designs, rows of octagons and stars, knot forms, and borders sometimes derived from kufic script. None of the carpets woven before 1500 AD have survived.[25]

The Safavid Period (1501–1732)

In 1499, a new dynasty arose in Persia. Shah Ismail I, its founder, was related to Uzun Hassan. He is regarded as the first national sovereign of Persia since the Arab conquest, and established Shi'a Islam as the state religion of Persia.[32] He and his successors, Shah Tahmasp I and Shah Abbas I became patrons of the Persian Safavid art. Court manufactories were probably established by Shah Tahmasp in Tabriz, but definitely by Shah Abbas when he moved his capital from Tabriz in northwestern to Isfahan in central Persia, in the wake of the Ottoman–Safavid War (1603–18). For the art of carpet weaving in Persia, this meant, as Edwards wrote: "that in a short time it rose from a cottage métier to the dignity of a fine art."[25]

The time of the Safavid dynasty marks one of the greatest periods in Persian art, which includes carpet weaving. Later Safavid period carpets still exist, which belong to the finest and most elaborate weavings known today. The phenomenon that the first carpets physically known to us show such accomplished designs leads to the assumption that the art and craft of carpet weaving must already have existed for some time before the magnificent Safavid court carpets could have been woven. As no early Safavid period carpets survived, research has focused on Timurid period book illuminations and miniature paintings. These paintings depict colourful carpets with repeating designs of equal-scale geometric patterns, arranged in checkerboard-like designs, with "kufic" border ornaments derived from Islamic calligraphy. The designs are so similar to period Anatolian carpets, especially to "Holbein carpets" that a common source of the design cannot be excluded: Timurid designs may have survived in both the Persian and Anatolian carpets from the early Safavid, and Ottoman period.[33]

The "design revolution"

By the late fifteenth century, the design of the carpets depicted in miniatures changed considerably. Large-format medaillons appeared, ornaments began to show elaborate curvilinear designs. Large spirals and tendrils, floral ornaments, depictions of flowers and animals, were often mirrored along the long or short axis of the carpet to obtain harmony and rhythm. The earlier "kufic" border design was replaced by tendrils and arabesques. All these patterns required a more elaborate system of weaving, as compared to weaving straight, rectilinear lines. Likewise, they require artists to create the design, weavers to execute them on the loom, and an efficient way to communicate the artist's ideas to the weaver. Today this is achieved by a template, termed cartoon (Ford, 1981, p. 170[34]). How Safavid manufacturers achieved this, technically, is currently unknown. The result of their work, however, was what Kurt Erdmann termed the "carpet design revolution".[35]

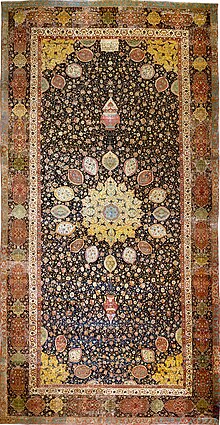

Apparently, the new designs were developed first by miniature painters, as they started to appear in book illuminations and on book covers as early as in the fifteenth century. This marks the first time when the "classical" design of Islamic rugs was established: The medaillon and corner design (pers.: "Lechek Torūnj") was first seen on book covers. In 1522, Ismail I employed the miniature painter Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, a famous painter of the Herat school, as director of the royal atelier. Behzad had a decisive impact on the development of later Safavid art. The Safavid carpets known to us differ from the carpets as depicted in the miniature paintings, so the paintings cannot support any efforts to differentiate, classify and date period carpets. The same holds true for European paintings: Unlike Anatolian carpets, Persian carpets were not depicted in European paintings before the seventeenth century.[36] As some carpets like the Ardabil carpets have inwoven inscriptions including dates, scientific efforts to categorize and date Safavid rugs start from them:

I have no refuge in the world other than thy threshold.

There is no protection for my head other than this door.

The work of the slave of the threshold Maqsud of Kashan in the year 946.— Inwoven inscription of the Ardabil carpet

The AH year of 946 corresponds to AD 1539–1540, which dates the Ardabil carpet to the reign of Shah Tahmasp, who donated the carpet to the shrine of Shaykh Safi-ad-din Ardabili in Ardabil, who is regarded as the spiritual father of the Safavid dynasty.

Another inscription can be seen on the "Hunting Carpet", now at the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan, which dates the carpet to 949 AH/AD 1542–3:

By the diligence of Ghyath ud-Din Jami was completed

This renowned work, that appeals to us by its beauty

In the year 949— Inwoven inscription of the Milan Hunting carpet

The number of sources for more precise dating and the attribution of provenience increase during the 17th century. Safavid carpets were presented as diplomatic gifts to European cities and states, as diplomatic relations intensified. In 1603, Shah Abbas presented a carpet with inwoven gold and silver threads to the Venetian doge Marino Grimani. European noblemen began ordering carpets directly from the manufactures of Isfahan and Kashan, whose weavers were willing to weave specific designs, like European coats of arms, into the commissioned peces. Their acquisition was sometimes meticulously documented: In 1601, the Armenian Sefer Muratowicz was sent to Kashan by the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa in order to commission 8 carpets with the Polish royal court of arms to be inwoven. The Kashan weavers did so, and on 12 September 1602 Muratowicz presented the carpets to the Polish king, and the bill to the treasurer of the crown.[36] Representative Safavid carpets made of silk with inwoven gold and silver threads were erroneously believed by Western art historians to be of Polish manufacture. Although the error was corrected, carpets of this type retained the name of "Polish" or "Polonaise" carpets. The more appropriate type name of "Shah Abbas" carpets was suggested by Kurt Erdmann.[36]

Masterpieces of Safavid carpet weaving

A. C. Edwards opens his book on Persian carpets with the description of eight masterpieces from this great period:

- Ardabil Carpet – Victoria and Albert Museum

- Hunting Carpet – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

- Chelsea Carpet – Victoria and Albert Museum

- Allover Animal and Floral Carpet – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna

- Rose-ground Vase Carpet – Victoria and Albert Museum

- Medaillion Animal and Floral Carpet with Inscription Guard – Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan

- Inscribed Medaillon Carpet with Animal and Flowers and Inscription Border – Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession Number: 32.16

- Medaillon, Animal, and Tree Carpet – Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

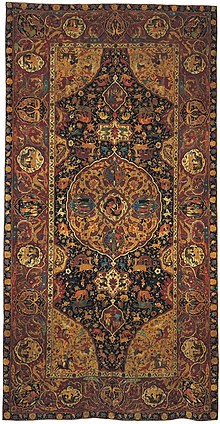

Safavid "Vase technique" carpets from Kirmān

A distinct group of Safavid carpets can be attributed to the region of Kirmān in southern Persia. May H. Beattie identified these carpets by their common structure:[37] Seven different types of carpets were identified: Garden carpets (depicting formal gardens and water channels); carpets with centralized designs, characterized by a large medallion; multiple-medaillon designs with offset medaillons and compartment repeats; directional designs with the arrangements of little scenes used as individual motifs; sickle-leaf designs where long, curved, serrated and sometimes compound leaves dominate the field; arabesque; and lattice designs. Their distinctive structure consists of asymmetric knots; the cotton warps are depressed, and there are three wefts. Woolen wefts lie hidden in the center of the carpet, making up the first and third weft. Silk or cotton makes up the middle weft, which crosses from back to front. A characteristic "tram line" effect is evoked by the third weft when the carpet is worn .

The best known "vase technique" carpets from Kirmān are those of the so-called "Sanguszko group", named after the House of Sanguszko, whose collection has the most outstanding example. The medallion-and-corner design is similar to other 16th century Safavid carpets, but the colours and style of drawing are distinct. In the central medallion, pairs of human figures in smaller medallions surround a central animal combat scene. Other animal combats are depicted in the field, while horsemen are shown in the corner medallions. The main border also contains lobed medallions with Houris, animal combats, or confronting peacocks. In-between the border medallions, phoenixes and dragons are fighting. By similarity to mosaic tile spandrels in the Ganjali Khan Complex at the Kirmān bazaar with an inscription recording its date of completion as 1006 AH/AD 1596, they are dated to the end of the 16th or the beginning of the 17th century.[38] Two other "vase technique" carpets have inscriptions with a date: One of them bears the date 1172 AH/AD 1758 and the name of the weaver: the Master Craftsman Muhammad Sharīf Kirmānī, the other has three inscriptions indicating that it was woven by the Master Craftsman Mu'min, son of Qutb al-Dīn Māhānī, between 1066-7 AH/AD 1655–1656. Carpets in the Safavid tradition were still woven in Kirmān after the fall of the Safavid dynasty in 1732 (Ferrier, 1989, p. 127[38]).

The end of Shah Abbas II's reign in 1666 marked the beginning of the end of the Safavid dynasty. The declining country was repeatedly raided on its frontiers. Finally, a Ghilzai Pashtun chieftain named Mir Wais Khan began a rebellion in Kandahar and defeated the Safavid army under the Iranian Georgian governor over the region, Gurgin Khan. In 1722, Peter the Great launched the Russo-Persian War (1722-1723), capturing many of Iran's Caucasian territories, including Derbent, Shaki, Baku, but also Gilan, Mazandaran and Astrabad. In 1722, an Afghan army led by Mir Mahmud Hotaki marched across eastern Iran, and besieged and took Isfahan. Mahmud proclaimed himself 'Shah' of Persia. Meanwhile, Persia's imperial rivals, the Ottomans and the Russians, took advantage of the chaos in the country to seize more territory for themselves.[39] With these events, the Safavid dynasty had come to an end.

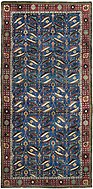

Gallery: Persian carpets from the Safavid Era

Zayn al-'Abidin bin ar-Rahman al-Jami – Early 16th century miniature, Walters Art Museum

Ardabil Carpet at the LACMA

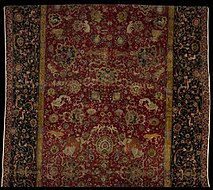

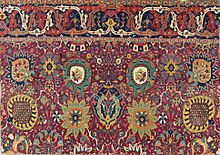

The Emperor's Carpet (detail), second half of the 16th century, Iran. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Niche rug with the text of the Ayat al-Kursi, c. 1570s central Iran, Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

- Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Persian_carpet

"Vase technique" carpet, Kirmān, 17th century

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.