A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

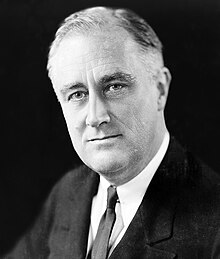

Roosevelt in 1933 | |

| Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt March 4, 1933 – April 12, 1945 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Democratic |

| Seat | White House |

First term March 4, 1933 – January 20, 1937 | |

| Election | 1932 |

Second term January 20, 1937 – January 20, 1941 | |

| Election | 1936 |

|

| |

| Library website | |

| |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||

The first term of the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt began on March 4, 1933, when he was inaugurated as the 32nd president of the United States, and the second term of his presidency ended on January 20, 1941, with his inauguration to a third term. Roosevelt, the Democratic governor of the largest state, New York, took office after defeating incumbent President Herbert Hoover, his Republican opponent in the 1932 presidential election. Roosevelt led the implementation of the New Deal, a series of programs designed to provide relief, recovery, and reform to Americans and the American economy during the Great Depression. He also presided over a realignment that made his New Deal Coalition of labor unions, big city machines, white ethnics, African Americans, and rural white Southerners dominant in national politics until the 1960s and defined modern American liberalism.

During his first hundred days in office, Roosevelt spearheaded unprecedented major legislation and issued a profusion of executive orders. The Emergency Banking Act helped put an end to a run on banks, while the 1933 Banking Act and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 provided major reforms in the financial sector. To provide relief to unemployed workers, Roosevelt presided over the establishment of several agencies, including the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Public Works Administration, and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. The Roosevelt administration established the Agricultural Adjustment Administration to implement new policies designed to prevent agricultural overproduction. It also established several agencies, most notably the National Recovery Administration, to reform the industrial sector, though it lasted only two years.

After his party's sweeping success in the 1934 mid-term elections, Roosevelt presided over the Second New Deal. It featured the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the largest work relief agency, and the Social Security Act, which created a national old-age pension program known as Social Security. The New Deal also established a national unemployment insurance program, as well as the Aid to Dependent Children, which provided aid to families headed by single mothers. A third major piece of legislation, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, guaranteed workers the right of collective bargaining and established the National Labor Relations Board. The result was rapid growth in union membership. After winning re-election in 1936, the second term was a series of disappointments. Roosevelt sought to enlarge the Supreme Court, but his proposal was defeated in Congress. Roosevelt had little success in passing domestic legislation in his second term, as the bipartisan Conservative Coalition blocked most of his legislative proposals. One success was the Fair Labor Standards Act.

The 1930s were a high point of isolationism in the United States. The key foreign policy initiative of Roosevelt's first term was the Good Neighbor Policy, in which the U.S. took a non-interventionist stance in Latin American affairs. Foreign policy issues came to the fore in the late 1930s, as Nazi Germany, Japan, and Italy took aggressive actions against their neighbors. In response to fears that the United States would be drawn into foreign conflicts, Congress passed the Neutrality Acts, a series of laws that prevented trade with belligerents. After Japan invaded China and Germany invaded Poland, Roosevelt provided aid to China, Great Britain, and France, but the Neutrality Acts prevented the United States from becoming closely involved. After the Fall of France in June 1940, Roosevelt increased aid to the British and began to build up American military power. In the 1940 presidential election, Roosevelt defeated Republican Wendell Willkie, an internationalist who largely refrained from criticizing Roosevelt's foreign policy. Roosevelt later went on to serve a third term and three months of a fourth term, becoming the only president to serve more than two terms, breaking Washington's two term tradition and laying the groundwork for the passage of the 22nd Amendment. Roosevelt's first term is unique in that it is the only presidential term not equal to four years in length since George Washington was elected to his second term, this was a result of the 20th Amendment. Although in reality this only effected Roosevelt's first Vice President, John Nance Garner.

1932 election

Democratic nomination

With the economy hurting badly after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, many Democrats hoped that the 1932 elections would see the election of the first Democratic president since 1916. Roosevelt's 1930 gubernatorial re-election victory in New York established him as the front-runner for the nomination. With the help of Louis Howe and James Farley, Roosevelt rallied some of the supporters of the Wilson while also appealing to many conservatives, establishing himself as the leading candidate in the South and West. The chief opposition to Roosevelt's candidacy came from Northeastern liberals such as Al Smith, the 1928 Democratic presidential nominee and a former close ally. Smith hoped to deny Roosevelt the two-thirds support necessary to win the party's presidential nomination 1932 Democratic National Convention, and then emerge as the nominee after multiple rounds of balloting. Roosevelt entered the convention with a delegate lead due to his success in the 1932 Democratic primaries, but most delegates entered the convention unbound to any particular candidate. On the first presidential ballot of the convention, Roosevelt received the votes of more than half but less than two-thirds of the delegates, with Smith finishing in a distant second place. Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, who controlled the votes of Texas and California, threw his support behind Roosevelt after the third ballot, and Roosevelt clinched the nomination on the fourth ballot. With little input from Roosevelt, Garner won the vice presidential nomination. Roosevelt flew in from New York after learning that he had won the nomination, becoming the first major party presidential nominee to accept the nomination in person.[1]

General election

In the general election, Roosevelt faced incumbent Republican President Herbert Hoover. Engaging in a cross-country campaign, Roosevelt promised to increase the federal government's role in the economy and to lower the tariff as part of a "New Deal." Hoover argued that the economic collapse had chiefly been the product of international disturbances, and he accused Roosevelt of promoting class conflict with his novel economic policies. Already unpopular due to the bad economy, Hoover's re-election hopes were further hampered by the Bonus March 1932, which ended with the violent dispersal of thousands of protesting veterans. Roosevelt won 472 of the 531 electoral votes and 57.4% of the popular vote, making him the first Democrat since 1876 to win a majority of the popular vote, and he won a larger percentage of the vote than any Democrat before him since the party's founding in 1828. In the concurrent congressional elections, the Democrats took control of the Senate and built upon their majority in the House.[2] Though congressional Democratic leadership was dominated by conservative Southerners, over half of the members of the incoming 73rd Congress had been elected since 1930. Many of these new members were eager to take action to combat the Depression, even if it meant defying the political orthodoxy of the previous years.[3]

Administration

| The Roosevelt cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt | 1933–1945 |

| Vice President | John Nance Garner | 1933–1941 |

| Henry A. Wallace | 1941–1945 | |

| Harry S. Truman | 1945 | |

| Secretary of State | Cordell Hull | 1933–1944 |

| Edward Stettinius Jr. | 1944–1945 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William H. Woodin | 1933 |

| Henry Morgenthau Jr. | 1934–1945 | |

| Secretary of War | George Dern | 1933–1936 |

| Harry Hines Woodring | 1936–1940 | |

| Henry L. Stimson | 1940–1945 | |

| Attorney General | Homer Stille Cummings | 1933–1939 |

| Frank Murphy | 1939–1940 | |

| Robert H. Jackson | 1940–1941 | |

| Francis Biddle | 1941–1945 | |

| Postmaster General | James Farley | 1933–1940 |

| Frank C. Walker | 1940–1945 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Claude A. Swanson | 1933–1939 |

| Charles Edison | 1939–1940 | |

| Frank Knox | 1940–1944 | |

| James Forrestal | 1944–1945 | |

| Secretary of the Interior | Harold L. Ickes | 1933–1945 |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Henry A. Wallace | 1933–1940 |

| Claude R. Wickard | 1940–1945 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | Daniel C. Roper | 1933–1938 |

| Harry Hopkins | 1938–1940 | |

| Jesse H. Jones | 1940–1945 | |

| Henry A. Wallace | 1945 | |

| Secretary of Labor | Frances Perkins | 1933–1945 |

Roosevelt appointed powerful men to top positions but made certain he made all the major decisions, regardless of delays, inefficiency or resentment. Analyzing the president's administrative style, historian James MacGregor Burns concludes:

- The president stayed in charge of his administration...by drawing fully on his formal and informal powers as Chief Executive; by raising goals, creating momentum, inspiring a personal loyalty, getting the best out of people...by deliberately fostering among his aides a sense of competition and a clash of wills that led to disarray, heartbreak, and anger but also set off pulses of executive energy and sparks of creativity...by handing out one job to several men and several jobs to one man, thus strengthening his own position as a court of appeals, as a depository of information, and as a tool of co-ordination; by ignoring or bypassing collective decision-making agencies, such as the Cabinet...and always by persuading, flattering, juggling, improvising, reshuffling, harmonizing, conciliating, manipulating.[4]

For his first Secretary of State, Roosevelt selected Cordell Hull, a prominent Tennessean who had served in the House and Senate. Though Hull was not a foreign policy expert, he was a long-time advocate of tariff reduction, was respected by his Senate colleagues, and did not hold ambitions for the presidency. Roosevelt's inaugural cabinet included several influential Republicans, including Secretary of the Treasury William H. Woodin, a well-connected industrialist who was personally close to Roosevelt, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, a progressive Republican who would play an important role in the New Deal, and Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, who had advised the Roosevelt campaign on farm policies. Roosevelt also appointed the first female cabinet member, Secretary of Labor Frances C. Perkins. Farley became Postmaster General, traking charge of major patronage issues. Howe became Roosevelt's personal secretary until his death in 1936.[5] The selections of Hull, Woodin, and Secretary of Commerce Daniel C. Roper reassured the business community, while Wallace, Perkins, and Ickes appealed to Roosevelt's left-wing supporters.[6] Most of Roosevelt's cabinet selections would remain in place until 1936, but ill health forced Woodin to resign in 1933, and he was succeeded by Henry Morgenthau Jr., who became the most powerful member of the cabinet, followed by Wallace.[7]

First term domestic affairs

First New Deal, 1933–34

When Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, the economy had hit bottom. In the midst of the Great Depression. A quarter of the American workforce was unemployed, two million people were homeless, and industrial production had fallen by more than half since 1929.[8] By the evening of March 4, 32 of the 48 states – as well as the District of Columbia – had closed their banks.[9] The New York Federal Reserve Bank was unable to open on the 5th, as huge sums had been withdrawn by panicky customers in previous days.[10] Beginning with his inauguration address, Roosevelt laid the blame for the economic crisis on bankers and financiers, the quest for profit, and the self-interest basis of capitalism:

Primarily this is because rulers of the exchange of mankind's goods have failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and have abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men. True they have tried, but their efforts have been cast in the pattern of an outworn tradition. Faced by failure of credit they have proposed only the lending of more money. Stripped of the lure of profit by which to induce our people to follow their false leadership, they have resorted to exhortations, pleading tearfully for restored confidence... The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.[11]

Historians categorize Roosevelt's economic program into three categories: "relief, recovery and reform." Relief was urgently needed by tens of millions of unemployed. Recovery meant boosting the economy back to normal. Reform meant long-term fixes of what was wrong, especially with the financial and banking systems. Through Roosevelt's series of radio talks, known as fireside chats, he presented his proposals directly to the American public.[12] To propose programs, Roosevelt relied on leading senators such as George Norris, Robert F. Wagner, and Hugo Black, as well as his Brain Trust of academic advisers. Like Hoover, he saw the Depression caused in part by people no longer spending or investing because they were afraid.[13]

Banking reform

Banking reform was the most urgent task facing the newly inaugurated administration. Thousands of smaller banks had failed or were on the verge of failing, and panicked depositors sought to remove their savings from banks for fear that they would lose their deposits after a bank failure. In the months after Roosevelt's election, several governors declared bank holidays, temporarily closing banks so that their deposits could not be withdrawn.[14] By the time Roosevelt took office, gubernatorial proclamations had closed the banks in 32 states; in the remaining states, many banks were closed and depositors were permitted to withdraw only five percent of their deposits.[15] On March 5, Roosevelt declared a federal bank holiday, closing every bank in the nation. Though some questioned Roosevelt's constitutional authority to declare a bank holiday, his action received little immediate political resistance in light of the severity of the crisis.[14] Working with the outgoing secretary of the treasury, Ogden Mills, the Roosevelt administration spent the next few days putting together a bill designed to rescue the banking industry.[16]

When the special session of Congress that had been called by Roosevelt opened on March 9, Congress quickly passed Roosevelt's Emergency Banking Act. Rather than nationalizing the financial industry, as some radicals hoped and many conservatives feared, the bill used federal assistance to stabilize privately owned banks.[17] The ensuing "First 100 Days" of the 73rd Congress saw an unprecedented amount of legislation[18] and set a benchmark against which future presidents would be compared.[19] When the banks reopened on Monday, March 13, stock prices rose by 15 percent and bank deposits exceeded withdrawals, thus ending the bank panic.[20]

In another measure designed to give Americans confidence in the financial system, Congress enacted the Glass–Steagall Act, which curbed speculation by limiting the investments commercial banks could make and ending affiliations between commercial banks and securities firms.[21] Depositors in open banks received insurance coverage from the new Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), while depositors in permanently closed banks were eventually repaid 85 cents on the dollar. Roosevelt himself was dubious about insuring bank deposits, saying, "We do not wish to make the United States Government liable for the mistakes and errors of individual banks, and put a premium on unsound banking in the future." But public support was overwhelmingly in favor, and the number of bank failures dropped to near zero.[22][23]

Relief for unemployed

Relief for the unemployed was a major priority for the New Deal, and Roosevelt copied the programs he had initiated as governor of New York as well as the programs Hoover had started.[24] The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the largest program from 1933 to 1935, involved giving money to localities to operate work relief projects to employ those on direct relief. FERA was led by Harry Hopkins, who had helmed a similar program under Roosevelt in New York.[25] Another agency, the Public Works Administration (PWA), was created to fund infrastructure projects, and was led by Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, one of the most aggressive of the New Deal empire builders.[26] Seeking to increase the federal role in providing work relief, Hopkins successfully pushed for the creation of the Civil Works Administration (CWA), which would provide employment for anyone who was unemployed. In less than four months, the CWA hired four million people, and during its five months of operation, the CWA built and repaired 200 swimming pools, 3,700 playgrounds, 40,000 schools, 250,000 miles (400,000 km) of road, and 12 million feet of sewer pipe.[27] The CWA was widely popular, but Roosevelt canceled it in March 1934 due to cost concerns and the fear of establishing a precedent that the government would serve as a permanent employer of last resort.[28]

The most popular of all New Deal agencies – and Roosevelt's favorite– was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).[29] The CCC hired 250,000 unemployed young men to work for six months on rural projects. It was directed by Robert Fechner, a former union executive who promised labor unions that the enrollees would not be trained in skills that would compete with unemployed union members. Instead, they did unskilled construction labor, especially building roads and recreational facilities in state and national parks. Each CCC camp was administered by an Army reserve officer. Food, clothing, supplies, and medical and dental services were purchased locally. The young men who worked at CCC camps were paid a dollar a day, most of which went to their parents. Blacks were enrolled in their own camps, and the CCC operated an entirely separate division for Indians.[30][31][32]

Agriculture

Roosevelt placed a high emphasis on agricultural issues.[33] Farmers made up thirty percent of the nation's workforce, and New Dealers hoped that an agricultural recovery would help stimulate the broader economy.[34] Leadership of the farm programs of the New Deal lay with Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, a dynamic, intellectual reformer.[35][36] The persistent farm crisis of the 1920s was further exacerbated by the onset of the Great Depression, and foreclosures were common among debt-ridden farms.[37] Farmers were locked in a vicious cycle in which low prices encouraged individual farmers to engage in greater production, which in turn lowered prices by providing greater supply. The Hoover administration had created the Federal Farm Board to help address the issue of overproduction by purchasing agricultural surpluses, but it failed to stabilize prices.[38] In the 1930s, Midwestern farmers would additionally have to contend with a series of severe dust storms known as the Dust Bowl, provoking migration from the affected regions.[39]

The 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The act reflected the demands of leaders of major farm organizations, especially the Farm Bureau, and reflected debates among Roosevelt's farm advisers such as Wallace, M.L. Wilson, Rexford Tugwell, and George Peek.[40] The aim of the AAA was to raise prices for commodities through artificial scarcity. The AAA used a system of "domestic allotments", setting the total output of corn, cotton, dairy products, hogs, rice, tobacco, and wheat. The AAA paid land owners subsidies for leaving some of their land idle; funding for the subsidies was provided by a new tax on food processing. The goal was to force up farm prices to the point of "parity," an index based on 1910–1914 prices. To meet 1933 goals, 10 million acres (40,000 km2) of growing cotton was plowed up, bountiful crops were left to rot, and six million piglets were killed and discarded.[41] Farm incomes increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal, as prices for commodities rose.[42] However, some sharecroppers suffered under the new system, as some landowners pocketed the federal subsidies distributed for keeping lands fallow.[43]

The AAA was the first federal agricultural program to operate on such a large scale, and it established a long-lasting federal role in the planning of the entire agricultural sector of the economy.[44][page needed] In 1936, the Supreme Court declared the AAA to be unconstitutional for technical reasons. With the passage of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, the AAA was replaced by a similar program that did win Court approval. Instead of paying farmers for letting fields lie barren, the new program subsidized them for planting soil enriching hay crops such as alfalfa that would not be sold on the market. Federal regulation of agricultural production has been modified many times since then, but the basic philosophy of subsidizing farmers remains in effect.[45]

Rural relief

Many rural families lived in severe poverty, especially in the South. Agencies such as the Resettlement Administration and its successor, the Farm Security Administration (FSA), represented the first national programs to help migrants and marginal farmers, whose plight gained national attention through the 1939 novel and film The Grapes of Wrath. New Deal leaders resisted demands of the poor for loans to buy farms, as many leaders thought that there were already too many farmers.[46] The Roosevelt administration made a major effort to upgrade the health facilities available to a sickly population.[47] The Farm Credit Administration refinanced many mortgages, reducing the number of displaced farming families. In 1935, the administration created the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), which built electric lines in rural areas providing electricity for the first time to millions.[48] In the decade following the establishment of the REA, the share of farms with electricity went from under 20 percent to approximately 90 percent.[49]

Roosevelt appointed John Collier to lead the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Collier presided over a shift in policy towards Native Americans that de-emphasized cultural assimilation. Native Americans worked in the CCC and other New Deal programs, including the newly formed Soil Conservation Service.[50]

In 1933, the administration launched the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a project involving dam construction planning on an unprecedented scale in order to curb flooding, generate electricity, and modernize the very poor farms in the Tennessee Valley region of the Southern United States.[51][52] Under the leadership of Arthur Ernest Morgan, the TVA built planned communities such as Norris, Tennessee that were designed to serve as models of cooperative, egalitarian living. Though the more ambitious experiments of the TVA generally failed to take hold, by 1940, the TVA had become the largest producer of electric power in the country.[53] The Roosevelt administration also established the Bonneville Power Authority, which performed similar functions to the TVA in the Pacific Northwest, albeit on a smaller scale.[54]

NRA for industry

The Roosevelt administration launched the National Recovery Administration (NRA) as one of the two major programs designed to restore economic prosperity, along with the AAA.[55] The NRA was established by the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, and was designed to implement reforms in the industrial sector.[56] The framers of the NRA were heavily influenced by the work of Charles R. Van Hise, a Progressive academic who saw trusts as an inevitable feature of an industrialized society. Rather than advocating for antitrust laws designed to prevent the growth of trusts, Hise had favored the creation of governmental organizations charged with regulating trusts.[57] The NRA tried to end cutthroat competition by forcing industries to come up with codes that established the rules of operation for all firms within specific industries, such as minimum prices, minimum wages, agreements not to compete, and production restrictions. Industry leaders negotiated the codes with the approval and guidance of NIRA officials. Other provisions encouraged the formation of unions and suspended anti-trust laws.[58]

Roosevelt appointed Hugh S. Johnson as the head of the NRA, based on his experience in directing the national economy in World War I. Johnson used the NRA to curb industrial overproduction and excessive competition through price cutting. He sought to keep wages high.[59] The NRA won the pledges of two million businesses to create and follow NRA codes, and Blue Eagle symbols, which indicated that a company cooperated with the NRA, became ubiquitous.[60] The NRA targeted ten essential industries deemed crucial to an economic recovery, starting with textile industry and next turning to coal, oil, steel, automobiles, and lumber. Though unwilling to dictate the codes to industries, the administration pressured companies to agree to the codes and urged consumers to purchase products from companies in compliance with the codes.[58] As each NRA code was unique to a specific industry, NRA negotiators held a great deal of sway in setting the details of the codes, and many of the codes favored managers over workers.[61] The NRA became increasingly unpopular among the general public due to its micromanagement, and many within the administration began to view it as ineffective.[62] The Supreme Court found the NRA to be unconstitutional by unanimous decision in May 1935, and there was little public protest at its closing.[63]

To replace the regulatory role of the NRA, the New Deal established or strengthened several durable agencies designed to regulate specific industries. In 1934, Congress established the Federal Communications Commission, which provided regulation to telephones and radio. The Civil Aeronautics Board was established in 1938 to regulate the fast-growing commercial aviation industry, while in 1935 the authority of the Interstate Commerce Commission was extended to the trucking industry. The Federal Trade Commission also received new duties.[64]

Monetary policy

The Agricultural Adjustment Act included the Thomas Amendment, a provision that allowed the president to reduce the gold content of the dollar, to coin silver dollars, and issue $3 billion in fiat money not backed by gold or silver. In April 1933, Roosevelt took the United States off the gold standard.[65] Going off the gold standard allowed Roosevelt to pursue inflationary policies, to overcome the sharp fall in prices that hurt the economy. Inflation would reduce the effective size of public and private debt. As part of his inflationary policies, Roosevelt refused to take part in efforts at the London Economic Conference to stabilize currency exchange rates.[66] Roosevelt's "bombshell" message to that conference effectively ended any major efforts by the world powers to collaborate on ending the worldwide depression, and allowed Roosevelt a free hand in economic policy.[67] Though Roosevelt was willing to negotiate regarding tariffs, he refused to accept a fixed exchange-rate system or to reduce European debts incurred during World War I.[68] In October 1933, the Roosevelt administration began a policy of buying gold in the hopes that such purchases would lead to inflation. The program was strongly criticized by observers like Keynes, as well as hard money administration officials such as Dean Acheson, but it did appease many in rural communities.[69] In 1935, Congress passed the Banking Act of 1935, which brought the Federal Open Market Committee under the direct control of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, thereby increasing the Federal Reserve's ability to control the money supply and respond to business cycles.[70]

Securities regulation

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 established the independent Securities and Exchange Commission to end irresponsible market manipulations and the dissemination of false information about securities.[71] Roosevelt named Joseph P. Kennedy, a famously successful speculator himself, to head the SEC and clean up Wall Street. Kennedy appointed a hard-driving team with a mission for reform that included William O. Douglas, and Abe Fortas, both of whom were later named to the Supreme Court.[72] The SEC had four missions. First and most important was to restore investor confidence in the securities market, which had practically collapsed because of doubts about its internal integrity, and the external threats supposedly posed by anti-business elements in the Roosevelt administration. Second, in terms of integrity, the SEC had to get rid of the penny ante swindles based on false information, fraudulent devices, and unsound get-rich-quick schemes. Thirdly, and much more important than the frauds, the SEC had to end the million-dollar insider maneuvers in major corporations, whereby insiders with access to information about the condition of the company knew when to buy or sell their own securities. Finally, the SEC had to set up a complex system of registration for all securities sold in America, with a clear-cut set of rules and guidelines that everyone had to follow.[73] By mandating the disclosure of business information and allowing investors to make informed decisions, the SEC largely succeed in its goal of restoring investor confidence.[74]

As part of the first hundred days, Roosevelt fostered the passage of the Securities Act of 1933. The act expanded the powers of the Federal Trade Commission and required companies issuing securities to disclose information regarding the securities they issued.[75] Another major securities law, the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, broke up large public utility holding companies. The law arose from concerns that the holding companies had used elaborate measures to extract profits from subsidiary utility companies while taking advantage of customers.[76]

Housing

House construction was widely seen as a potential component of an economic recovery. Though Keynes and Senator Wagner both favored large-scale public housing projects, the Roosevelt administration prioritized programs designed to boost private home-ownership. In 1933, Roosevelt established the Home Owners' Loan Corporation, which helped prevent mortgage foreclosures by offering refinancing programs. The Federal Housing Administration, established in 1934, set national home construction standards and provided insurance to long-term home mortgages. Another New Deal institution, Fannie Mae, made home lending more appealing to lenders by helping to provide for the securitization of mortgages, thereby allowing mortgages to be sold on the secondary mortgage market. The housing institutions established under the New Deal did not appreciably contribute to new house building in the 1930s, but they played a major role in the post-war housing boom.[77]

Ending prohibition

Roosevelt had generally avoided the Prohibition issue, but when his party and the general public swung against Prohibition in 1932, he campaigned for repeal. During the Hundred Days he signed the Cullen–Harrison Act redefining weak beer (3.2% alcohol) as the maximum allowed. The 21st Amendment was ratified later that year; he was not involved in the amendment but was given much of the credit. The repeal of prohibition brought in new tax revenues to federal, state and local governments and helped Roosevelt keep a campaign promise that attracted widespread popular support. It also weakened the big-city criminal gangs and rural bootleggers who had profited heavily from illegal liquor sales.[78][79]

Second New Deal, 1935–36

The "Second New Deal" is the designation historians use for the dramatic domestic policies passed during the last two years of Roosevelt's first term. Unlike his efforts in the first two years to be inclusive of all established interest groups, Roosevelt moved left and focused on helping labor unions, poor farmers, and the unemployed. He energetically battled growing opposition from conservatives, business and banking interests.[80]

WPA

By 1935, the economy was 21% bigger than its nadir, but the real gross national product was still 11% below the apex reached in 1929. It finally caught up and passed 1929 during 1936. Unemployment remained a major problem at 20%. However farm incomes were recovering.[81][82] With the economy still in depression, and following Democratic triumphs in the 1934 mid-term elections, Roosevelt proposed the "Second New Deal." It consisted of government programs that were designed to help provide not just recovery, but also long-term stability and security for ordinary Americans.[83] In April 1935, Roosevelt won passage of the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935, which, unlike the work relief programs of 1933, allowed for a long-term role for the government as the employer of last resort. Roosevelt, among others, feared that the private sector would never again be able to provide full employment on its own. The major program created by the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act was the Works Progress Administration (WPA), led by Harry Hopkins.[84] The WPA financed a variety of projects such as hospitals, schools, and roads, and employed more than 8.5 million workers who built 650,000 miles of highways and roads, 125,000 public buildings, as well as bridges, reservoirs, irrigation systems, and other projects.[85] Ickes's PWA continued to function, but the WPA became the primary New Deal work relief program,[86] and FERA was discontinued.[87][page needed] Though nominally charged only with undertaking construction projects that cost over $25,000, the WPA provided grants for other programs, such as the Federal Writers' Project.[88]

Like the CWA and the CCC, the WPA typically was based on collaboration with local government, which provided the plans, the site, and the heavy equipment, while the federal government provided the labor. Building new recreational facilities in public parks fit the model, and tens of thousands of recreation and sports facilities were built in both rural and urban areas. These projects had the main goal of providing jobs for the unemployed, but they also played to a widespread demand at the time for bodily fitness and the need of recreation in a healthy society. Roosevelt was a strong supporter of the recreation and sports dimension of his programs. The WPA spent $941 million on recreational facilities, including 5,900 athletic fields and playgrounds, 770 swimming pools 1,700 parks and 8,300 recreational buildings.[89][90]

National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a semi-autonomous unit within the WPA. It worked closely with high schools and colleges to set up work-study programs.[91][92] Under the leadership of Aubrey Williams, the NYA developed apprenticeship programs and residential camps specializing in teaching vocational skills. It was one of the first agencies that made an explicit effort to enroll black students. The NYA work-study program reached up to 500,000 students per month in high schools, colleges, and graduate schools.[93][94] The NYA also set up its own high schools, entirely separate from the public school system or academic schools of education.[95][96]

Social Security

The United States was the lone modern industrial country where people faced the Depression without any national system of social security, though a handful of states had poorly-funded old-age insurance programs.[97] The federal government had provided pensions to veterans in the aftermath of the Civil War and other wars, and some states had established voluntary old-age pension systems, but otherwise the United States had little experience with social insurance programs.[98] For most American workers, retirement due to old age was not a realistic option.[99] In the 1930s, physician Francis Townsend galvanized support for his pension proposal, which called for the federal government to issue direct $200-a-month payments to the elderly.[100] Roosevelt was attracted to the general thinking behind Townsend's plan because it would provide for those no longer capable of working while at the same time stimulating demand in the economy and decreasing the supply of labor.[101] In 1934, Roosevelt charged the Committee on Economic Security, chaired by Secretary of Labor Perkins, with developing an old-age pension program, an unemployment insurance system, and a national health care program. The proposal for a national health care system was dropped, but the committee developed an unemployment insurance program largely administered by the states. The committee also developed an old-age plan that, at Roosevelt's insistence, would be funded by individual contributions from workers.[102]

In January 1935, Roosevelt proposed the Social Security Act, which he presented as a more practical alternative to the Townsend Plan. After a series of congressional hearings, the Social Security Act became law in August 1935.[103] During the congressional debate over Social Security, the program was expanded to provide payments to widows and dependents of Social Security recipients.[104] Job categories that were not covered by the act included workers in agricultural labor, domestic service, government employees, and many teachers, nurses, hospital employees, librarians, and social workers.[105] The program was funded through a newly established a payroll tax which later became known as the Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax. Social Security taxes would be collected from employers by the states, with employers and employees contributing equally to the tax.[106] Because the Social Security tax was regressive, and Social Security benefits were based on how much each individual had paid into the system, the program would not contribute to income redistribution in the way that some reformers, including Perkins, had hoped.[107] In addition to creating the Social Security program, the Social Security Act also established a state-administered unemployment insurance system and the Aid to Dependent Children program, which provided aid to families headed by single mothers.[108] Compared with the social security systems in western European countries, the Social Security Act of 1935 was rather conservative. But for the first time the federal government took responsibility for the economic security of the aged, the temporarily unemployed, dependent children and the handicapped.[109] Reflecting the continuing importance of the Social Security Act, biographer Kenneth S. Davis later called the Social Security Act "the most important single piece of social legislation in all American history."[110]

Though the Committee on Economic Security had originally sought to develop a national health care system, the Social Security Act ultimately included only relatively small health care grants designed to help rural communities and the disabled.[111] Roosevelt declined to include a large-scale health insurance program largely because of the lack of active popular, congressional, or interest group support for such a program. Roosevelt's strategy was to wait for demand for a program to materialize, and then, if he thought it popular enough, to throw his support behind it. Jaap Kooijman writes that Roosevelt succeeded in "pacifying the opponents without discouraging the reformers." During World War II, a group of congressmen introduced the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill, which would provide federally funded universal health care. Roosevelt never endorsed it, and with conservatives in control of Congress, it stood little chance of passage. Health insurance would be proposed in Truman's Fair Deal, but it was defeated.[112][113]

Labor unions and the NLRB

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRB) of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, guaranteed workers the right to collective bargaining through unions of their own choice. It prohibited unfair labor practices such as discrimination against union members. The act also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to facilitate wage agreements and to suppress labor disturbances. The Wagner Act did not compel employers to reach agreement with their employees, but, together with the Norris–La Guardia Act of 1932, its passage left labor unions in a favorable legal and political environment.[114] Other factors, including popular works that depicted the struggles of the working class, declining ethnic rivalries, and the La Follette Committee's investigation of anti-labor abuses, further swung the public mood in favor of labor.[115] The result was a tremendous growth of membership in the labor unions, especially in the mass-production sector.[116] When the Flint sit-down strike threatened the production of General Motors, Roosevelt broke with the precedent set by many former presidents and refused to intervene; the strike ultimately led to the unionization of both General Motors and its rivals in the American automobile industry.[117] In the aftermath of the Flint sit-down strike, U.S. Steel granted recognition to the Steel Workers Organizing Committee.[118] The total number of labor union members grew from three million in 1933 to eight million at the end of the 1930s, with the vast majority of union members living outside of the South.[119]

Other domestic policies

Fiscal policy

Roosevelt argued that the emergency spending programs for relief were temporary, and he rejected the deficit spending proposed by economists such as John Maynard Keynes.[120] He kept his campaign promise to cut the regular federal budget — including a reduction in military spending from $752 million in 1932 to $531 million in 1934. He made a 40% cut in spending on veterans' benefits by removing 500,000 veterans and widows from the pension rolls and reducing benefits for the remainder, as well as cutting the salaries of federal employees and reducing spending on research and education. The veterans were well organized and strongly protested, and most benefits were restored or increased by 1934.[121] In June 1933, Roosevelt restored $50 million in pension payments, and Congress added another $46 million more.[122] Veterans groups such as the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars also won their campaign to transform their benefits from payments due in 1945 to immediate cash when Congress overrode the president's veto and passed the Bonus Act in January 1936.[123][124][page needed] The Bonus Act pumped sums equal to 2% of the GDP into the consumer economy and had a major stimulus effect.[125] Government spending increased from 8.0% of gross national product (GNP) under Hoover in 1932 to 10.2% of the GNP in 1936.[126]

In mid-1935, Roosevelt began to prioritize a major reform of the tax code. He sought higher taxes on top incomes, a higher estate tax, a graduated corporate tax, and the implementation of a tax on intercorporate dividends. In response, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1935, which raised relatively little revenue but did increase taxes on the highest earners. A top tax rate of 79% was set for income above $5 million; in 1935, just one individual, John D. Rockefeller, paid the top tax rate.[127] In early 1936, following the passage of the Bonus Act, Roosevelt again sought to increase taxes on corporate profits. Congress passed a bill that raised less revenue that Roosevelt's proposals, but did impose an undistributed profits tax on corporate earnings.[128]

Conservation and the environment

Roosevelt had a lifelong interest in the environment and conservation starting with his youthful interest in forestry on his family estate. Although FDR was never an outdoorsman or sportsman on TR's scale, his growth of the national systems were comparable. FDR created 140 national wildlife refuges (especially for birds) and established 29 national forests and 29 national parks and monuments,[129][page needed][130][page needed] including Everglades National Park and Olympic National Park.[54] His environmental policy can be divided into three major domains. First of all his focus was on a few issues that had long concerned environmentalists: clean air and water, land management, preservation of forest lands, protection of wildlife, conservation of natural resources, and the creation of national parks and monuments.[131] Second, he created permanent institutional structures with environmental missions, including permanent institutions like the Tennessee Valley Authority and temporary operations such as the CCC.[132] Finally, Roosevelt was a superb communicator with the people, and with Congress, using speeches and especially highly publicized trips visiting key conservation locales.[133]

Roosevelt's favorite agency, the CCC, expended most of its effort on environmental projects. In the dozen years after its creation, the CCC built 13,000 miles of trails, planted two billion trees, and upgraded 125,000 miles of dirt roads. Every state had its own state parks, and Roosevelt made sure that WPA and CCC projects were set up to upgrade them as well as the national systems.[134][135] Roosevelt was particularly supportive of water management projects, which could provide hydroelectricity, improve river navigation, and supply water for irrigation. His administration initiated the construction of numerous dams located in the South and the West. Although proposals to replicate the Tennessee Valley Authority in the Pacific Northwest were not acted upon, the administration completed the All-American Canal and launched the Central Valley Project, both of which irrigated dramatically increased agricultural production in California's Central Valley. Roosevelt also presided over the establishment of conservation programs and laws such as the Soil Conservation Service, the Great Plains Shelterbelt, and the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934.[136]

Throughout his first two terms there was a fierce turf battle over control of the United States Forest Service, which Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace insisted on keeping, but Interior Secretary Harold Ickes wanted so he could merge it with the National Park Service. The Brownlow Committee report on administrative management convinced Roosevelt to propose the creation of a new Department of Conservation to replace the Department of the Interior; the new department that would include the Forest Service. For Ickes, the land itself had a higher purpose than mere human usage; Wallace wanted the optimum economic productivity of public lands. Both Interior and Agriculture had very strong supporters in Congress, and Roosevelt's plan went nowhere. The status quo triumphed.[137][138]

Educationedit

The New Deal approach to education was a radical departure from previous practices. It was specifically designed for the poor and staffed largely by women on relief. It was not based on professionalism, nor was it designed by experts. Instead it was premised on the anti-elitist notion that a good teacher does not need paper credentials, that learning does not need a formal classroom and that the highest priority should go to the bottom tier of society. Leaders in the public schools were shocked: they were shut out as consultants and as recipients of New Deal funding. They desperately needed cash to cover the local and state revenues that it disappeared during the depression, they were well organized, and made repeated concerted efforts in 1934, 1937, and 1939, all to no avail. The federal government had a highly professional Office of Education; Roosevelt cut its budget and staff, and refused to consult with its leader John Ward Studebaker.[139] The CCC programs were deliberately designed not teach skills that would put them in competition with unemployed union members. The CCC did have its own classes. They were voluntary, took place after work, and focused on teaching basic literacy to young men who had dropped out before entering high school. The NYA set up its own high schools independent of the locally controlled public schools.[140]

The relief programs did offer indirect help to public schools. The CWA and FERA focused on hiring unemployed people on relief, and putting them to work on public buildings, including public schools. It built or upgraded 40,000 schools, plus thousands of playgrounds and athletic fields. It gave jobs to 50,000 teachers to keep rural schools open and to teach adult education classes in the cities. It gave a temporary jobs to unemployed teachers in cities like Boston.[141][142] Although New Deal leaders refused to give money to impoverished school districts, it did give money to impoverished high school and college students. The CWA used "work study" programs to fund students, both male and female.[143]

Womenedit

Women received recognition from the Roosevelt administration. In relief programs, they were eligible for jobs if they were the breadwinner in the family. During the 1930s there was a strong national consensus that in times of job shortages, it was wrong for the government to employ both a husband and his wife.[144] Nevertheless, relief agencies did find jobs for women, and the WPA employed about 500,000. The largest number, 295,000, worked on sewing projects, producing 300 million items of clothing and mattresses for people on relief and for public institutions such as orphanages. Many other women worked in school lunch programs.[145][146][147] Between 1929 and 1939, the percentage of female government employees increased from 14.3 percent to 18.8 percent, and women made up nearly half of the workforce of the WPA.[148] From 1930 to 1940, the number of employed women rose 24 percent from 10.5 million to 13 million. Few women worked in the high-unemployment sectors like mining and heavy industry. They worked in clerical jobs or light factories (such as food).[149]

Roosevelt appointed more women to office than any previous president. The very first woman in the cabinet was Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins.[150] Roosevelt also appointed Florence E. Allen to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, making her the first woman to serve on a federal appeals court.[151] First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt played a highly visible role in building a network of women in advisory roles and in promoting relief programs. The New Deal thereby placed more women in public life—a record that stood until the 1960s.[152] In 1941 Mrs. Roosevelt became co-head of the Office of Civil Defense, the major civil defense agency. She tried to involve women at the local level, but she feuded with her counterpart, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, and had little impact on policy.[150] Historian Alan Brinkley states that gender equality was not on the national agenda:

- Nor did the New Deal make much more than a symbolic effort to address problems of gender equality....New Deal programs (even those designed by New Deal women) continued most mostly to reflect traditional assumptions about women's roles and made few gestures toward the aspirations of women who sought economic independence and professional opportunities. The interest in individual and group rights that became so central to the postwar liberalism... was faint, and at times almost invisible, within the New Deal itself.[153]

Second term "Curse"edit

Despite expectations that the 1936 landslide heralded an expansion of liberal programs, everything went wrong for the New Dealers. The Democrats feuded and divided, with even Vice President Garner breaking with the president. The labor movement grew stronger but then began fighting itself, while the economy declined sharply. Anti-Roosevelt forces gained strength and the New Deal Coalition lost heavily in the 1938 midterm elections. Roosevelt suffered what historians call the "second term curse." The victors were overconfident, ignoring the administration's weaknesses. The minority party after losing two elections was eager to strike back.[154][155] Lawrence Summers states:

- Franklin Roosevelt’s second term was the least successful part of his presidency, as it saw the failure of his effort to pack the Supreme Court and a major economic relapse in 1938 and no accomplishment remotely comparable to the New Deal or his wartime leadership.[156]

Supreme Court fightedit

| Supreme Court appointments by President Franklin D. Roosevelt | ||

|---|---|---|

| Position | Name | Term |

| Chief Justice | Harlan Fiske Stone | 1941–1946 |

| Associate Justice | Hugo Black | 1937–1971 |

| Stanley Forman Reed | 1938–1957 | |

| Felix Frankfurter | 1939–1962 | |

| William O. Douglas | 1939–1975 | |

| Frank Murphy | 1940–1949 | |

| James F. Byrnes | 1941–1942 | |

| Robert H. Jackson | 1941–1954 | |

| Wiley Blount Rutledge | 1943–1949 | |

For the entirety of Roosevelt's first term, the Court consisted of the liberal "Three Musketeers," the conservative "Four Horsemen," and the two swing votes in Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justice Owen Roberts.[157] The more conservative members of the court adhered to principles of the Lochner era, a period in which courts had struck down numerous economic regulations on the basis of freedom of contract.[158] Reformers like Theodore Roosevelt had long protested the judicial activism of the courts, and Franklin Roosevelt's ambitious domestic programs inevitably came to the attention of the Supreme Court. The court struck down a major New Deal program for the first time through its holding in the 1935 case of A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, and the following year it struck down the AAA in the case of United States v. Butler.[159] By the beginning of 1937, the Court had cases on the docket regarding the constitutionality of the Social Security Act and the National Labor Relations Act.[160]

The Supreme Court's holdings had led many to seek to restrict its power through constitutional amendment, but the difficulty of amending the constitution caused Roosevelt to turn to a legislative remedy.[161] After winning re-election, Roosevelt proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, which would have allowed him to appoint an additional justice for each incumbent justice over the age of 70; in 1937, there were six Supreme Court Justices over the age of 70. The size of the Court had been set at nine since the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1869, and Congress had altered the number of justices six other times throughout U.S. history.[162] Roosevelt argued that the bill was necessary for reasons of judicial efficiency, but it was widely understood that his real goal was to appoint sympathetic justices.[163] What Roosevelt saw as a necessary and measured reform, many throughout the country saw as an attack on the principle of judicial independence, and critics labeled the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 as the "court packing" plan.[164] Roosevelt's proposal ran into intense political opposition from his own party, led by Vice President Garner.[165] A bipartisan coalition of liberals and conservatives of both parties opposed the bill, and Chief Justice Hughes broke with precedent by publicly advocating defeat of the bill. Any chance of passing the bill ended with the death of Senate Majority Leader Joseph Taylor Robinson in July 1937, after Roosevelt had expended crucial political capital on the failed bill.[166] The Court packing fight cost Roosevelt the support of some liberals, such as Montana Senator Burton K. Wheeler.[167] and commentator Walter Lippmann.[168]

In early 1937, while the debate over the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 continued, the Supreme Court handed down its holding in the case of West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish. In a 5–4 decision, the Court upheld a state minimum wage law that was similar to a state law that the court had struck down the year before; the difference between the cases was that Roberts switched his vote. The case was widely seen as an important shift in the Court's judicial philosophy, and one newspaper called Roberts's vote "the switch in time that saved nine" because it effectively ended any chance of passing the court-packing bill. Later in 1937, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the NLRB and the major provisions of the Social Security Act. One of the Four Horsemen, Willis Van Devanter, stepped down that same year, giving Roosevelt his first opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court justice, and several more Supreme Court vacancies followed.[169] By the end of his second term in January 1941, Roosevelt had appointed Stanley Forman Reed,[170] Felix Frankfurter,[171] William O. Douglas,[172] and Frank Murphy[173] to the Supreme Court. After Parish, the Court shifted its focus from judicial review of economic regulations to the protection of civil liberties.[174][page needed]

Roosevelt never added new seats but he did replace the old justices as they retired. In his first appointment he made the highly controversial nomination of Alabama Senator Hugo Black. The nomination was controversial because Black was an ardent New Dealer with almost no judicial experience. It was well known that the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama supported him. Black was quiet but his friends denied he had ever been a KKK member. After he was confirmed his KKK membership became known and a second firestorm exploded. Black and Roosevelt waited it out and Black went on to become a prominent champion of civil liberties.[175]

Second term legislationedit

With Roosevelt's influence on the wane following the failure of the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, conservative Democrats joined with Republicans to block the implementation of further New Deal regulatory programs.[176] Led by Senator Josiah Bailey, a bipartisan group of congressmen issued the Conservative Manifesto, which articulated the conservative opposition to the growth of labor unions, taxation, regulations, and relief programs that had occurred under the New Deal.[177] Roosevelt did manage to pass some legislation as long as it had enough Republican support. The Housing Act of 1937 built 270,000 public housing units by 1939. The second Agricultural Adjustment Act, which re-established the AAA, had bipartisan support from the farm lobby.[178] The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which was the last major piece of New Deal legislation, outlawed child labor, established a federal minimum wage, and required overtime pay for certain employees who worked in excess of forty-hours per week.[179] It had support from some Northern Republicans worried about the competition from low-wage Southern factories.[180]

The stock market suffered a major drop in 1937, marking the start of an economic downturn within the Great Depression known as the Recession of 1937–38. Influenced by economists such as Keynes, Marriner Stoddard Eccles, and William Trufant Foster, Roosevelt abandoned his fiscally conservative positions in favor of economic stimulus funding. By increasing government spending, Roosevelt hoped to increase consumption, which in turn would allow private employers to hire more workers and drive down the unemployment rate. In mid-1938, Roosevelt authorized new loans to private industry by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and he won congressional approval for over $4 billion in appropriations for the WPA, the FSA, the PWA, and other programs.[182]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Presidency_of_Franklin_D._Roosevelt,_first_and_second_terms

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.