A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| History of Indiana | |

|---|---|

The seal of Indiana reflects the state's pioneer era | |

| Historical Periods | |

| Pre-history | until 1670 |

| French Rule | 1679–1763 |

| British Rule | 1763–1783 |

| U.S. Territorial Period | 1783–1816 |

| Indiana Statehood | 1816–present |

| Major Events | |

| Tecumseh's War War of 1812 | 1811–1814 |

| Constitutional convention | June 1816 |

| Polly v. Lasselle | 1820 |

| Capitol moved to Indianapolis | 1825 |

| Passage of the Mammoth Internal Improvement Act | 1831 |

| State Bankruptcy | 1841 |

| 2nd Constitution | 1851 |

| Civil War | 1860–1865 |

| Gas Boom | 1887–1905 |

| Harrison elected president | 1888 |

| KKK scandal | 1925 |

The history of human activity in Indiana, a U.S. state in the Midwest, stems back to the migratory tribes of Native Americans who inhabited Indiana as early as 8000 BC. Tribes succeeded one another in dominance for several thousand years and reached their peak of development during the period of Mississippian culture. The region entered recorded history in the 1670s, when the first Europeans came to Indiana and claimed the territory for the Kingdom of France. After France ruled for a century (with little settlement in this area), it was defeated by Great Britain in the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) and ceded its territory east of the Mississippi River. Britain held the land for more than twenty years, until after its defeat in the American Revolutionary War, then ceded the entire trans-Allegheny region, including what is now Indiana, to the newly formed United States.

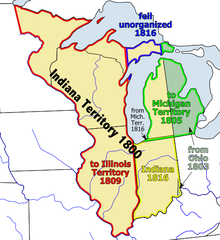

The U.S. government divided the trans-Allegheny region into several new territories. The largest of these was the Northwest Territory, which the U.S. Congress subsequently subdivided into several smaller territories. In 1800, Indiana Territory became the first of these new territories established. As Indiana Territory grew in population and development, it was divided in 1805 and again in 1809 until, reduced to its current size and boundaries, it retained the name Indiana and was admitted to the Union December 11, 1816 as the nineteenth state.

The newly established state government set out on an ambitious plan to transform Indiana from a segment of the frontier into a developed, well-populated, and thriving state. State founders initiated an internal improvement program that led to the construction of roads, canals, railroads, and state-funded public schools. Despite the noble aims of the project, profligate spending ruined the state's credit. By 1841, the state was near bankruptcy and was forced to liquidate most of its public works. Acting under its new Constitution of 1851, the state government enacted major financial reforms, required that most public offices be filled by election rather than appointment, and greatly weakened the power of the governor. The ambitious development program of Indiana's founders was realized when Indiana became the fourth-largest state in terms of population, as measured by the 1860 census.

Indiana became politically influential and played an important role in the Union during the American Civil War. Indiana was the first western state to mobilize for the war, and its soldiers participated in almost every engagement during the war. Following the Civil War, Indiana remained politically important as it became a critical swing state in U.S. presidential elections. It helped decide control of the presidency for three decades.

During the Indiana Gas Boom of the late 19th century, industry began to develop rapidly in the state. The state's Golden Age of Literature began in the same time period, increasing its cultural influence. By the early 20th century, Indiana developed into a strong manufacturing state and attracted numerous immigrants and internal migrants to its industries. It experienced setbacks during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Construction of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, expansion of the auto industry, urban development, and two wars contributed to the state's industrial growth. During the second half of the 20th century, Indiana became a leader in the pharmaceutical industry due to the innovations of companies such as Indiana based Eli Lilly.

Early civilizations

Following the end of the last glacial period, about twenty thousand years ago, Indiana's topography was dominated by spruce and pine forests and was home to mastodon, caribou, and saber-toothed cats. While northern Indiana had been covered by glaciers, southern Indiana remained unaltered by the ice's advance, leaving plants and animals that could sustain human communities.[1][2] Indiana's earliest known inhabitants were Paleo-Indians. Evidence exists that humans were in Indiana as early as the Archaic stage (8000–6000 BC).[3] Hunting camps of the nomadic Clovis culture have been found in Indiana.[4] Carbon dating of artifacts found in the Wyandotte Caves of southern Indiana shows humans mined flint there as early 2000 BC.[5] These nomads ate quantities of freshwater mussels from local streams, as shown by their shell mounds found throughout southern Indiana.[5]

The Early Woodland period in Indiana came between 1000 BC and 200 AD and produced the Adena culture. It domesticated wild squash and made pottery, which were large cultural advances over the Clovis culture. The natives built burial mounds; one of this type has been dated as the oldest earthwork in Anderson's Mounds State Park.[6]

Natives in the Middle Woodland period developed the Hopewell culture and may have been in Indiana as early as 200 BC. The Hopewells were the first culture to create permanent settlements in Indiana. About 1 AD, the Hopewells mastered agriculture and grew crops of sunflowers and squash. Around 200 AD, the Hopewells began to construct mounds used for ceremonies and burials. The Hopewells in Indiana were connected by trade to other native tribes as far away as Central America.[7] For unknown reasons, the Hopewell culture went into decline around 400 and completely disappeared by 500.[8]

The Late Woodland era is generally considered to have begun about 600 AD and lasted until the arrival of Europeans in Indiana. It was a period of rapid cultural change. One of the new developments—which has yet to be explained—was the introduction of masonry, shown by the construction of large, stone forts, many of which overlook the Ohio River. Romantic legend attributed the forts to Welsh Indians, who supposedly arrived centuries before Christopher Columbus reached the Caribbean;[9] however, archaeologists and other scholars have found no evidence for that theory and believe that the cultural development was engendered by the Mississippian culture.[10]

Mississippians

Evidence suggests that after the collapse of the Hopewell, Indiana had a low population until the rise of the Fort Ancient and Mississippian culture around 900 AD.[11] The Ohio River Valley was densely populated by the Mississippians from about 1100 to 1450 AD. Their settlements, like those of the Hopewell, were known for their ceremonial earthwork mounds. Some of these remain visible at locations near the Ohio River. The Mississippian mounds were constructed on a grander scale than the mounds built by the Hopewell. The agrarian Mississippian culture was the first to grow maize in the region. The people also developed the bow and arrow and copper working during this time period.[11]

Mississippian society was complex, dense, and highly developed; the largest Mississippian city of Cahokia (in Illinois) contained as many as 30,000 inhabitants. They had a class society with certain groups specializing as artisans. The elite held related political and religious positions. Their cities were typically sited near rivers. Representing their cosmology, the central developments were dominated by a large central mound, several smaller mounds, and a large open plaza. Wooden palisades were built later around the complex, apparently for defensive purposes.[11] The remains of a major settlement known as Angel Mounds lie east of present-day Evansville.[12] Mississippian houses were generally square-shaped with plastered walls and thatched roofs.[13] For reasons that remain unclear, the Mississippians disappeared in the middle of the 15th century, about 200 years before the Europeans first entered what would become modern Indiana. Mississippian culture marked the high point of native development in Indiana.[11]

It was during this period that American Bison began a periodic east–west trek through Indiana, crossing the Falls of the Ohio and the Wabash River near modern-day Vincennes. These herds became important to civilizations in southern Indiana and created a well-established Buffalo Trace, later used by European-American pioneers moving west.[14]

Before 1600, a major war broke out in eastern North America among Native Americans; it was later called the Beaver Wars. Five American Indian Iroquois tribes confederated to battle against their neighbors. The Iroquois were opposed by a confederation of primarily Algonquian tribes including the Shawnee, Miami, Wea, Pottawatomie, and the Illinois.[15] These tribes were significantly less advanced than the Mississippian culture that had preceded them. The tribes were semi-nomadic, used stone tools rather than copper, and did not create the large-scale construction and farming works of their Mississippian predecessors. The war continued with sporadic fighting for at least a century as the Iroquois sought to dominate the expanding fur trade with the Europeans. They achieved this goal for several decades. During the war, the Iroquois drove the tribes from the Ohio Valley to the south and west. They kept control of the area for hunting grounds.[16][17]

As a result of the war, several tribes, including the Shawnee, migrated into Indiana, where they attempted to resettle in land belonging to the Miami. The Iroquois gained the military advantage after they were supplied with firearms by the Europeans. With their superior weapons, the Iroquois subjugated at least thirty tribes and nearly destroyed several others in northern Indiana.[18]

European contact

When the first Europeans entered Indiana during the 1670s, the region was in the final years of the Beaver Wars. The French attempted to trade with the Algonquian tribes in Indiana, selling them firearms in exchange for furs. This incurred the wrath of the Iroquois, who destroyed a French outpost in Indiana in retaliation. Appalled by the Iroquois, the French continued to supply the western tribes with firearms and openly allied with the Algonquian tribes.[19][20] A major battle—and a turning point in the conflict—occurred near present-day South Bend when the Miami and their allies repulsed a large Iroquois force in an ambush.[21] With the firearms they received from the French, the odds were evened. The war finally ended in 1701 with the Great Peace of Montreal. Both Indian confederacies were left exhausted, having suffered heavy casualties. Much of Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana was depopulated after many tribes fled west to escape the fighting.[22]

The Miami and Pottawatomie nations returned to Indiana following the war.[23][24] Other tribes, such as the Algonquian Lenape, were pushed westward into the Midwest from the East Coast by encroachment of European colonists. Around 1770 the Miami invited the Lenape to settle on the White River.[25][note 1] The Shawnee arrived in present-day Indiana after the three other nations.[23] These four nations were later participants in the Sixty Years' War, a struggle between native nations and European settlers for control of the Great Lakes region. Hostilities with the tribes began early. The Piankeshaw killed five French fur traders in 1752 near the Vermilion River. However, the tribes also traded successfully with the French for decades.[26]

Colonial period

French fur traders from Canada were the first Europeans to enter Indiana, beginning in the 1670s.[27] The quickest route connecting the New France districts of Canada and Louisiana ran along Indiana's Wabash River. The Terre Haute highlands were once considered the border between the two French districts.[28] Indiana's geographical location made it a vital part of French lines of communication and trade routes. The French established Vincennes as a permanent settlement in Indiana during European rule, but the population of the area remained primarily Native American.[29] As French influence grew in the region, Great Britain, competing with France for control of North America, came to believe that control of Indiana was important to halt French expansion on the continent.[30]

France

The first European outpost within the present-day boundaries of Indiana was Tassinong, a French trading post established in 1673 near the Kankakee River.[note 2] French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, came to the area in 1679, claiming it for King Louis the XIV of France. La Salle came to explore a portage between the St. Joseph and Kankakee rivers,[31] and Father Ribourde, who traveled with La Salle, marked trees along the way. The marks survived to be photographed in the 19th century.[32] In 1681, La Salle negotiated a common defense treaty between the Illinois and Miami nations against the Iroquois.[33]

Further exploration of Indiana led to the French establishing an important trade route between Canada and Louisiana via the Maumee and Wabash rivers. The French built a series of forts and outposts in Indiana as a hedge against the westward expansion of the British colonies from the east coast of North America and to encourage trade with the native tribes. The tribes were able to procure metal tools, cooking utensils, and other manufactured items in exchange for animal pelts. The French built Fort Miamis in the Miami town of Kekionga (modern-day Fort Wayne, Indiana). France assigned Jean Baptiste Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes, as the first agent to the Miami at Kekionga.[34]

In 1717, François-Marie Picoté de Belestre[note 3] established the post of Fort Ouiatenon (southwest of modern-day West Lafayette, Indiana) to discourage the Wea from coming under British influence.[35] In 1732, François-Marie Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes, established a similar post near the Piankeshaw in the town that still bears his name. Although the forts were garrisoned by men from New France, Fort Vincennes was the only outpost to maintain a permanent European presence until the present day.[36] Jesuit priests accompanied many of the French soldiers into Indiana in an attempt to convert the natives to Christianity. The Jesuits conducted missionary activities, lived among the natives and learned their languages, and accompanied them on hunts and migrations. Gabriel Marest, one of the first missionaries in Indiana, taught among the Kaskaskia as early as 1712. The missionaries came to have great influence among the natives and played an important role in keeping the native tribes allied with the French.[37]

During the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War in Europe, the British directly challenged France for control of the region. Although no pitched battles occurred in Indiana, the native tribes of the region supported the French.[38] At the beginning of the war, the tribes sent large groups of warriors to support the French in resisting the British advance and to raid British colonies.[39] Using Fort Pitt as a forward base, British commander Robert Rogers overcame the native resistance and drove deep into the frontier to capture Fort Detroit. The rangers moved south from Detroit and captured many of the key French outposts in Indiana, including Fort Miamis and Fort Vincennes.[40] As the war progressed, the French lost control of Canada after the fall of Montreal. No longer able to effectively fight the British in interior North America, they lost Indiana to British forces. By 1761, the French were entirely forced out of Indiana.[41] Following the French expulsion, native tribes led by Chief Pontiac confederated in an attempt to rebel against the British without French assistance. While Pontiac was besieging British-held Fort Detroit, other tribes in Indiana rose up against the British, who were forced to surrender Fort Miamis and Fort Ouiatenon.[42] In 1763, while Pontiac was fighting the British, the French signed the Treaty of Paris and ceded control of Indiana to the British.[43]

Great Britain

When the British gained control of Indiana, the entire region was in the middle of Pontiac's Rebellion. During the next year, British officials negotiated with the various tribes, splitting them from their alliance with Pontiac. Eventually, Pontiac lost most of his allies, forcing him to make peace with the British on July 25, 1766. As a concession to Pontiac, Great Britain issued a proclamation that the territory west of the Appalachian Mountains was to be reserved for Native Americans.[44] Despite the treaty, Pontiac was still considered a threat to British interests, but after he was murdered on April 20, 1769, the region saw several years of peace.[45]

After Britain established peace with the natives, many of the former French trading posts and forts in the region were abandoned. Fort Miamis was maintained for several years because it was considered to be "of great importance", but even it was eventually abandoned.[46] The Jesuit priests were expelled, and no provisional government was established; the British hoped the French in the area would leave. Many did leave, but the British gradually became more accommodating to the French who remained and continued the fur trade with the Native American nations.[47]

Formal use of the word Indiana dates from 1768, when a Philadelphia-based trading company gave their land claim in the present-day state of West Virginia the name of Indiana in honor of its previous owners, the Iroquois. Later, ownership of the claim was transferred to the Indiana Land Company, the first recorded use of the word Indiana. However, the Virginia colony argued that it was the rightful owner of the land because it fell within its geographic boundaries. The U.S. Supreme Court extinguished the land company's right to the claim in 1798.[48]

In 1773, the territory that included present-day Indiana was brought under the administration of Province of Quebec to appease its French population. The Quebec Act was one of the Intolerable Acts that the thirteen British colonies cited as a reason for the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. The Thirteen Colonies thought themselves entitled to the territory for their support of Great Britain during the French and Indian War, and were incensed that it was given to the enemy the colonies had been fighting.[49]

Although the United States gained official possession of the region following the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War, British influence on its Native American allies in the region remained strong, especially near Fort Detroit. This influence caused the Northwest Indian War, which began when British-influenced native tribes refused to recognize American authority and were backed in their resistance by British merchants and officials in the area. American military victories in the region and the ratification of the Jay Treaty, which called for British withdrawal from the region's forts, caused a formal evacuation, but the British were not fully expelled from the area until the conclusion of the War of 1812.[50]

United States

After the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, George Rogers Clark was sent from Virginia to enforce its claim to much of the land in the Great Lakes region.[51] In July 1778, Clark and about 175 men crossed the Ohio River and took control of Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes, along with several other villages in British Indiana. The occupation was accomplished without firing a shot because Clark carried letters from the French ambassador stating that France supported the Americans. These letters made most of the French and Native American inhabitants of the area unwilling to support the British.[52]

The fort at Vincennes, which the British had renamed Fort Sackville, had been abandoned years earlier and no garrison was present when the Americans arrived to occupy it. Captain Leonard Helm became the first American commandant at Vincennes. To counter Clark's advance, British forces under Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton recaptured Vincennes with a small force. In February 1779, Clark arrived at Vincennes in a surprise winter expedition and retook the town, capturing Hamilton in the process. This expedition secured most of southern Indiana for the United States.[53]

In 1780, emulating Clark's success at Vincennes, French officer Augustin de La Balme organized a militia force of French residents to capture Fort Detroit. While marching to Detroit, the militia stopped to sack Kekionga.[why?] The delay proved fatal when the expedition met Miami warriors led by Chief Little Turtle along the Eel River. The entire militia was killed or captured. Clark organized another assault on Fort Detroit in 1781, but it was aborted when Chief Joseph Brant captured a significant part of Clark's army at a battle known as Lochry's Defeat, near present-day Aurora, Indiana.[51] Other minor skirmishes occurred in Indiana, including the battle at Petit fort in 1780.[54] In 1783, when the war came to an end, Britain ceded the entire trans-Allegheny region to the United States—including Indiana—under the terms of the Treaty of Paris.[55]

Clark's militia was under the authority of the Commonwealth of Virginia, although a Continental Flag was flown over Fort Sackville, which he renamed Fort Patrick Henry in honor of an American patriot. Later that year, the areas formerly known as Illinois Country and Ohio Country were organized as Illinois County, Virginia until the colony relinquished its control of the area to the U.S. government in 1784.[56] Clark was awarded large tracts of land in southern Indiana for his service in the war. Present-day Clark County and Clarksville are named in his honor.[57]

Indiana Territory

Northwest Indian War

Passage of the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 committed the U.S. government to continued plans for western expansion, causing increasing tensions with native tribes who occupied the western lands. In 1785 the conflict erupted into the Northwest Indian War.[58][59] American troops made several unsuccessful attempts to end the native rebellion. During the fall of 1790, U.S. troops under the command of General Josiah Harmar pursued the Miami tribe near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana, but had to retreat. Major Jean François Hamtramck's expedition to other native villages in the area also failed when it was forced to return to Vincennes due to lack of sufficient provisions.[60][61] In 1791 Major General Arthur St. Clair, who was also the Northwest Territory's governor, commanded about 2,700 men in a campaign to establish a chain of forts in the area near the Miami capital of Kekionga; however, nearly a 1,000 warriors under the leadership of Chief Little Turtle launched a surprise attack on the American camp, forcing the militia's retreat. St. Clair's Defeat remains the U.S. Army's worst by Native Americans in history. Casualties included 623 federal soldiers killed and another 258 wounded; the Indian confederacy lost an estimated 100 men.[62][63]

St. Clair's loss led to the appointment of General "Mad Anthony" Wayne, who organized the Legion of the United States and defeated a Native American force at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in August 1794.[63][64] The Treaty of Greenville (1795) ended the war and marked the beginning of a series of land cession treaties. Under the terms of the Treaty, native tribes ceded most of southern and eastern Ohio and a strip of southeastern Indiana to the U.S. government. This ethnic cleansing opened the area for white settlement. Fort Wayne was built at Kekionga to represent United States sovereignty over the Ohio-Indiana frontier. After the treaty was signed, the powerful Miami nation considered themselves allies of the United States.[65][66] During the 18th century, Native Americans were victorious in 31 of the 37 recorded incidents with white settlers in the territory.[67]

Territory formation

The Congress of the Confederation formed the Northwest Territory under the terms of the Northwest Ordinance on July 13, 1787. This territory, which initially included land bounded by the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio River, was subsequently partitioned into the Indiana Territory (1800), Michigan Territory (1805), and the Illinois Territory (1809), and later became the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of eastern Minnesota. The Northwest Ordinance outlined the basis for government in these western lands and an administrative structure to oversee the territory, as well as a process for achieving statehood, while the Land Ordinance of 1785 called for the U.S. government to survey the territory for future sale and development.[68]

On May 7, 1800, the U.S. Congress passed legislation to establish the Indiana Territory, effective July 4, 1800, by dividing the Northwest Territory in preparation for Ohio's statehood, which occurred in 1803.[69] At the time the Indiana Territory was created, there were only two main American settlements in what became the state of Indiana: Vincennes and Clark's Grant. When the Indiana Territory was established in 1800 its total white population was 5,641; however, its Native American population was estimated to be nearly 20,000, but may have been as high as 75,000.[70][71]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=History_of_Indiana

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.