A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Current distribution of Indigenous peoples of the Americas | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Approximately 62 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 11.8 - 23.2 million[1][2] | |

| 3.7 - 9.7 million[3] | |

| 6.4 million[4] | |

| 5.9 million[5] | |

| 4.1 million[6] | |

| 2.2 million[7] | |

| 2.1 million[8] | |

| 1.9 million[9] | |

| 1.8 million[10] | |

| 1.7 million[11] | |

| 1.3 million[12] | |

| 1.3 million[13] | |

| 724,592[14] | |

| 601,019[15] | |

| 443,847[16] | |

| 417,559[17] | |

| 117,150[18] | |

| 104,143[19] | |

| 78,492[20] | |

| 76,452[21] | |

| 50,189[22] | |

| 36,507[23] | |

| 20,344[24] | |

| 19,839[25] | |

| ~19,000[26] | |

| 13,310[27] | |

| 3,280[28] | |

| 2,576[29] | |

| 1,394[30] | |

| 951[31] | |

| 327[32] | |

| 162[33] | |

| 8[34] | |

| Languages | |

| Numerous Indigenous American languages (both extant and extinct) Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, Danish, Dutch, and (formerly) Russian (historically in Alaska) | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Christianity (Catholic and Protestant), along with various Indigenous American religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Métis, Mestizos, Zambos, and Pardos. Distantly related to some Indigenous Siberian peoples | |

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are groups of people native to a specific region that inhabited the Americas before the arrival of European settlers in the 15th century and the ethnic groups who continue to identify themselves with those peoples.[35]

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are diverse; some Indigenous peoples were historically hunter-gatherers, while others traditionally practice agriculture and aquaculture. In some regions, Indigenous peoples created pre-contact monumental architecture, large-scale organized cities, city-states, chiefdoms, states, kingdoms, republics, confederacies and empires.[36] These societies had varying degrees of knowledge of engineering, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, writing, physics, medicine, planting and irrigation, geology, mining, metallurgy, sculpture and gold smithing.

Many parts of the Americas are still populated by Indigenous peoples; some countries have sizeable populations, especially Bolivia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru and the United States. At least a thousand different Indigenous languages are spoken in the Americas, where there are also 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone. Several of these languages are recognized as official by several governments such as those in Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay and Greenland. Some, such as Quechua, Arawak, Aymara, Guaraní, Mayan and Nahuatl, count their speakers in the millions. Whether contemporary Indigenous people live in rural communities or urban ones, many also maintain additional aspects of their cultural practices to varying degrees, including religion, social organization and subsistence practices. Like most cultures, over time, cultures specific to many Indigenous peoples have also evolved, preserving traditional customs but also adjusting to meet modern needs. Some Indigenous peoples still live in relative isolation from Western culture and a few are still counted as uncontacted peoples.[37] Indigenous peoples from the Americas have also formed diaspora communities outside the Western Hemisphere, namely in former colonial centers in Europe. A notable example is the sizable Greenlandic Inuit community in Denmark.[38] In the 20th and 21st centuries, Indigenous peoples from Suriname and French Guiana migrated to the Netherlands and France, respectively.[39][40]

Terminology

Application of the term "Indian" originated with Christopher Columbus, who, in his search for India, thought that he had arrived in the East Indies.[41][42][43][44][45][46]

The islands came to be known as the "West Indies", a name that is still used to describe the islands. This led to the blanket term "Indies" and "Indians" (Spanish: indios; Portuguese: índios; French: indiens; Dutch: indianen) for the Indigenous inhabitants, which implied some kind of ethnic or cultural unity among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This unifying concept, codified in law, religion, and politics, was not originally accepted by the myriad groups of Indigenous peoples themselves but has since been embraced or tolerated by many over the last two centuries.[47] Even though the term "Indian" generally does not include the culturally and linguistically distinct Indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions of the Americas, including the Aleuts, Inuit, or Yupik peoples, who entered the continent as a second, more recent wave of migration several thousand years later and have much more recent genetic and cultural commonalities with the Indigenous peoples of Siberia—these groups are nonetheless considered "Indigenous peoples of the Americas".[48]

The term Amerindian, a portmanteau of "American Indian", was coined in 1902 by the American Anthropological Association. It has been controversial ever since its creation. It was immediately rejected by some leading members of the Association, and, while adopted by many, it was never universally accepted.[49] While never popular in Indigenous communities themselves, it remains a preferred term among some anthropologists, notably in some parts of Canada and the English-speaking Caribbean.[50][51][52][53]

"Indigenous peoples in Canada" is used as the collective name for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.[54][55] The term Aboriginal peoples as a collective noun (also describing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) is a specific term of art used in some legal documents, including the Constitution Act, 1982,[56] though in most Indigenous circles Aboriginal has also fallen into disfavor.[57] Over time, as societal perceptions and government–indigenous relationships have shifted, many historical terms have changed definitions or been replaced as they have fallen out of favor.[58] The use of the term "Indian" is frowned upon because it represents the imposition and restriction of Indigenous peoples and cultures by the Canadian Government.[58] The terms "Native" and "Eskimo" are generally regarded as disrespectful, and so are rarely used unless specifically required.[59] While "Indigenous peoples" is the preferred term, many individuals or communities may choose to describe their identity using a different term.[58][59]

The Métis people of Canada can be contrasted, for instance, to the Indigenous-European mixed-race mestizos (or caboclos in Brazil) of Hispanic America who, with their larger population (in most Latin American countries constituting either outright majorities, pluralities, or at the least large minorities), identify largely as a new ethnic group distinct from both Europeans and Indigenous, but still considering themselves a subset of the European-derived Hispanic or Brazilian peoplehood in culture and ethnicity (cf. ladinos).

Among Spanish-speaking countries, indígenas or pueblos indígenas ('Indigenous peoples') is a common term, though nativos or pueblos nativos ('native peoples') may also be heard; moreover, aborigen ('aborigine') is used in Argentina and pueblos originarios ('original peoples') is common in Chile. In Brazil, indígenas and povos originários ('Indigenous peoples') are common formal-sounding designations, while índio ('Indian') is still the more often heard term (the noun for the South-Asian nationality being indiano), but for the past 10 years has been considered offensive and pejorative.[citation needed] Aborígene and nativo are rarely used in Brazil in Indigenous-specific contexts (e.g., aborígene is usually understood as the ethnonym for Indigenous Australians). The Spanish and Portuguese equivalents to Indian, nevertheless, could be used to mean any hunter-gatherer or full-blooded Indigenous person, particularly to continents other than Europe or Africa—for example, indios filipinos.[citation needed]

Indigenous peoples of the United States are commonly known as Native Americans, Indians, as well as Alaska Natives.[clarification needed] The term "Indian" is still used in some communities and remains in use in the official names of many institutions and businesses in Indian Country.[60]

Name controversy

The various nations, tribes, and bands of Indigenous peoples of the Americas have differing preferences in terminology for themselves.[61] While there are regional and generational variations in which umbrella terms are preferred for Indigenous peoples as a whole, in general, most Indigenous peoples prefer to be identified by the name of their specific nation, tribe, or band.[61][62]

Early settlers often adopted terms that some tribes used for each other, not realizing these were derogatory terms used by enemies. When discussing broader subsets of peoples, naming has often been based on shared language, region, or historical relationship.[63] Many English exonyms have been used to refer to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Some of these names were based on foreign language terms used by earlier explorers and colonists, while others resulted from the colonists' attempts to translate or transliterate endonyms from the native languages. Other terms arose during periods of conflict between the colonists and Indigenous peoples.[64]

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been more vocal about how they want to be addressed, pushing to suppress the use of terms widely considered to be obsolete, inaccurate, or racist. During the latter half of the 20th century and the rise of the Indian rights movement, the United States federal government responded by proposing the use of the term "Native American", to recognize the primacy of Indigenous peoples' tenure in the nation.[65] As may be expected among people of over 400 different cultures in the US alone, not all of the people intended to be described by this term have agreed on its use or adopted it. No single group naming convention has been accepted by all Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Most prefer to be addressed as people of their tribe or nations when not speaking about Native Americans/American Indians as a whole.[66]

Since the 1970s, the word "Indigenous", which is capitalized when referring to people, has gradually emerged as a favored umbrella term. The capitalization is to acknowledge that Indigenous peoples have cultures and societies that are equal to Europeans, Africans, and Asians.[62][67] This has recently been acknowledged in the AP Stylebook.[68] Some consider it improper to refer to Indigenous people as "Indigenous Americans" or to append any colonial nationality to the term because Indigenous cultures existed before European colonization. Indigenous groups have territorial claims that are different from modern national and international borders, and when labeled as part of a country, their traditional lands are not acknowledged. Some who have written guidelines consider it more appropriate to describe an Indigenous person as "living in" or "of" the Americas, rather than calling them "American"; or simply calling them "Indigenous" without any addition of a colonial state.[69][70]

History

Peopling of the Americas

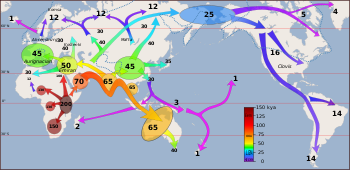

The peopling of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers (Paleo-Indians) entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum (26,000 to 19,000 years ago).[72] These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and spread rapidly southward, occupying both North and South America, by 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[73][74][75][76][77] The earliest populations in the Americas, before roughly 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.[78][79]

While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled from Asia, the pattern of migration and the place(s) of origin in Eurasia of the peoples who migrated to the Americas remain unclear.[74] The traditional theory is that Ancient Beringians moved when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation,[80][81] following herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[82] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America as far as Chile.[83] Any archaeological evidence of coastal occupation during the last Ice Age would now have been covered by the sea level rise, up to a hundred metres since then.[84]

The precise date for the peopling of the Americas is a long-standing open question, and while advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have progressively shed more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved.[85][86] The "Clovis first theory" refers to the hypothesis that the Clovis culture represents the earliest human presence in the Americas about 13,000 years ago.[87] Evidence of pre-Clovis cultures has accumulated and pushed back the possible date of the first peopling of the Americas.[88][89][90][91] Academics generally believe that humans reached North America south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet at some point between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago.[85][88][92][93][94][95] Some new controversial archaeological evidence suggests the possibility that human arrival in the Americas may have occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum more than 20,000 years ago.[88][96][97][98][99]Pre-Columbian era

While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus' voyages of 1492 to 1504, in practice the term usually includes the history of Indigenous cultures until Europeans either conquered or significantly influenced them.[103] "Pre-Columbian" is used especially often in the context of discussing the pre-contact Mesoamerican Indigenous societies: Olmec; Toltec; Teotihuacano' Zapotec; Mixtec; Aztec and Maya civilizations; and the complex cultures of the Andes: Inca Empire, Moche culture, Muisca Confederation, and Cañari.

The Pre-Columbian era refers to all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European and African influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original arrival in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonization during the early modern period.[104] The Norte Chico civilization (in present-day Peru) is one of the defining six original civilizations of the world, arising independently around the same time as that of Egypt.[105][106] Many later pre-Columbian civilizations achieved great complexity, with hallmarks that included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, engineering, astronomy, trade, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first significant European and African arrivals (ca. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are known only through oral history and through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with the contact and colonization period and were documented in historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Mayan, Olmec, Mixtec, Aztec, and Nahua peoples, had their written languages and records. However, the European colonists of the time worked to eliminate non-Christian beliefs and burned many pre-Columbian written records. Only a few documents remained hidden and survived, leaving contemporary historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.

According to both Indigenous and European accounts and documents, American civilizations before and at the time of European encounter had achieved great complexity and many accomplishments.[107] For instance, the Aztecs built one of the largest cities in the world, Tenochtitlan (the historical site of what would become Mexico City), with an estimated population of 200,000 for the city proper and a population of close to five million for the extended empire.[108] By comparison, the largest European cities in the 16th century were Constantinople and Paris with 300,000 and 200,000 inhabitants respectively.[109] The population in London, Madrid, and Rome hardly exceeded 50,000 people. In 1523, right around the time of the Spanish conquest, the entire population in the country of England was just under three million people.[110] This fact speaks to the level of sophistication, agriculture, governmental procedure, and rule of law that existed in Tenochtitlan, needed to govern over such a large citizenry. Indigenous civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in astronomy and mathematics, including the most accurate calendar in the world.[citation needed] The domestication of maize or corn required thousands of years of selective breeding, and continued cultivation of multiple varieties was done with planning and selection, generally by women.

Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Indigenous creation myths tell of a variety of origins of their respective peoples. Some were "always there" or were created by gods or animals, some migrated from a specified compass point, and others came from "across the ocean".[111]

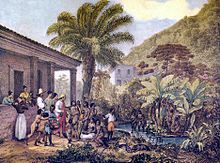

European colonization

The European colonization of the Americas fundamentally changed the lives and cultures of the resident Indigenous peoples. Although the exact pre-colonization population count of the Americas is unknown, scholars estimate that Indigenous populations diminished by between 80% and 90% during the first centuries of European colonization. Most scholars estimate a pre-colonization population of around 50 million, with other scholars arguing for an estimate of 100 million. Estimates reach as high as 145 million.[112][113][114]

Epidemics ravaged the Americas with diseases, such as smallpox, measles, and cholera, which the early colonists brought from Europe. The spread of infectious diseases was slow initially, as most Europeans were not actively or visibly infected, due to inherited immunity from generations of exposure to these diseases in Europe. This changed when the Europeans began the human trafficking of massive numbers of enslaved Western and Central African people to the Americas. Like Indigenous peoples, these African people, newly exposed to European diseases, lacked any inherited resistance to the diseases of Europe. In 1520 an African who had been infected with smallpox had arrived in Yucatán. By 1558, the disease had spread throughout South America and had arrived at the Plata basin.[115] Colonist violence towards Indigenous peoples accelerated the loss of lives. European colonists perpetrated massacres on the Indigenous peoples and enslaved them.[116][117][118] According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1894), the North American Indian Wars of the 19th century had a known death toll of about 19,000 Europeans and 30,000 Native Americans, and an estimated total death toll of 45,000 Native Americans.[119]

The first Indigenous group encountered by Columbus, the 250,000 Taínos of Hispaniola, represented the dominant culture in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. Within thirty years about 70% of the Taínos had died.[120] They had no immunity to European diseases, so outbreaks of measles and smallpox ravaged their population.[121] One such outbreak occurred in a camp of enslaved Africans, where smallpox spread to the nearby Taíno population and reduced their numbers by 50%.[115] Increasing punishment of the Taínos for revolting against forced labor, despite measures put in place by the encomienda, which included religious education and protection from warring tribes,[122] eventually led to the last great Taíno rebellion (1511–1529).

Following years of mistreatment, the Taínos began to adopt suicidal behaviors, with women aborting or killing their infants and men jumping from cliffs or ingesting untreated cassava, a violent poison.[120] Eventually, a Taíno Cacique named Enriquillo managed to hold out in the Baoruco Mountain Range for thirteen years, causing serious damage to the Spanish, Carib-held plantations and their Indian auxiliaries.[123][failed verification] Hearing of the seriousness of the revolt, Emperor Charles V (also King of Spain) sent Captain Francisco Barrionuevo to negotiate a peace treaty with the ever-increasing number of rebels. Two months later, after consultation with the Audencia of Santo Domingo, Enriquillo was offered any part of the island to live in peace.

The Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513, were the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spanish settlers in America, particularly concerning Indigenous peoples. The laws forbade the maltreatment of them and endorsed their conversion to Catholicism.[124] The Spanish crown found it difficult to enforce these laws in distant colonies.

Epidemic disease was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous peoples.[125][126] After initial contact with Europeans and Africans, Old World diseases caused the deaths of 90 to 95% of the native population of the New World in the following 150 years.[127] Smallpox killed from one-third to half of the native population of Hispaniola in 1518.[128][129] By killing the Incan ruler Huayna Capac, smallpox caused the Inca Civil War of 1529–1532. Smallpox was only the first epidemic. Typhus (probably) in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, and measles in 1618—all ravaged the remains of Inca culture.

Smallpox killed millions of native inhabitants of Mexico.[130][131] Unintentionally introduced at Veracruz with the arrival of Pánfilo de Narváez on 23 April 1520, smallpox ravaged Mexico in the 1520s,[132] possibly killing over 150,000 in Tenochtitlán (the heartland of the Aztec Empire) alone, and aiding in the victory of Hernán Cortés over the Aztec Empire at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) in 1521.[citation needed][115]

There are many factors as to why Indigenous peoples suffered such immense losses from Afro-Eurasian diseases. Many European diseases, like cow pox, are acquired from domesticated animals that are not indigenous to the Americas. European populations had adapted to these diseases, and built up resistance, over many generations. Many of the European diseases that were brought over to the Americas were diseases, like yellow fever, that were relatively manageable if infected as a child, but were deadly if infected as an adult. Children could often survive the disease, resulting in immunity to the disease for the rest of their lives. But contact with adult populations without this childhood or inherited immunity would result in these diseases proving fatal.[115][133]

Colonization of the Caribbean led to the destruction of the Arawaks of the Lesser Antilles. Their culture was destroyed by 1650. Only 500 had survived by the year 1550, though the bloodlines continued through to the modern populace. In Amazonia, Indigenous societies weathered, and continue to suffer, centuries of colonization and genocide.[134]

Contact with European diseases such as smallpox and measles killed between 50 and 67 percent of the Indigenous population of North America in the first hundred years after the arrival of Europeans.[135] Some 90 percent of the native population near Massachusetts Bay Colony died of smallpox in an epidemic in 1617–1619.[136] In 1633, in Fort Orange (New Netherland), the Native Americans there were exposed to smallpox because of contact with Europeans. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population groups of Native Americans.[137] It reached Lake Ontario in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois by 1679.[138][139] During the 1770s smallpox killed at least 30% of the West Coast Native Americans.[140] The 1775–82 North American smallpox epidemic and the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic brought devastation and drastic population depletion among the Plains Indians.[141][142] In 1832 the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans (The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832).[143]

The Indigenous peoples in Brazil declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated three million[144] to some 300,000 in 1997.[dubious ][failed verification][145]

The Spanish Empire and other Europeans re-introduced horses to the Americas. Some of these animals escaped and began to breed and increase their numbers in the wild.[146] The reintroduction of the horse, extinct in the Americas for over 7500 years, had a profound impact on Indigenous cultures in the Great Plains of North America and in the Gran Chaco and Patagonia in South America. By domesticating horses, some tribes had great success: horses enabled them to expand their territories, exchange more goods with neighboring tribes, and more easily capture game, especially bison.

According to Erin McKenna and Scott L. Pratt, the Indigenous population of the Americas was 145 million in the late 15th and by the late 17th century, had been reduced to 15 million due to epidemics, wars, massacres, mass rapes, starvation, and enslavement.[114]

Indigenous historical trauma

Indigenous historical trauma (IHT) is the trauma that can accumulate across generations and develop as a result of the historical ramifications of colonization and is linked to mental and physical health hardships and population decline.[147] IHT affects many different people in a multitude of ways because the Indigenous community and their history are diverse.

Many studies (such as Whitbeck et al., 2014;[148] Brockie, 2012; Anastasio et al., 2016;[149] Clark & Winterowd, 2012;[150] Tucker et al., 2016)[151] have evaluated the impact of IHT on health outcomes of Indigenous communities from the United States and Canada. IHT is a difficult term to standardize and measure because of the vast and variable diversity of Indigenous people and their communities. Therefore, it is an arduous task to assign an operational definition and systematically collect data when studying IHT. Many of the studies that incorporate IHT measure it in different ways, making it hard to compile data and review it holistically. This is an important point that provides context for the following studies that attempt to understand the relationship between IHT and potential adverse health impacts.

Some of the methodologies to measure IHT include a "Historical Losses Scale" (HLS), "Historical Losses Associated Symptoms Scale" (HLASS), and residential school ancestry studies.[147]: 23 HLS uses a survey format that includes "12 kinds of historical losses", such as loss of language and loss of land and asks participants how often they think about those losses.[147]: 23 The HLASS includes 12 emotional reactions, and asks participants how they feel when they think about these losses.[147] Lastly, the residential school ancestry studies ask respondents if their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, or "elders from their community" went to a residential school to understand if family or community history in residential schools is associated with negative health outcomes.[147]: 25 In a comprehensive review of the research literature, Joseph Gone and colleagues[147] compiled and compared outcomes for studies using these IHT measures relative to the health outcomes of Indigenous peoples. The study defined negative health outcomes to include such concepts as anxiety, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, polysubstance abuse, PTSD, depression, binge eating, anger, and sexual abuse.[147]

The connection between IHT and health conditions is complicated because of the difficult nature of measuring IHT, the unknown directionality of IHT and health outcomes, and because the term Indigenous people used in the various samples comprises a huge population of individuals with drastically different experiences and histories. That being said some studies such as Bombay, Matheson, and Anisman (2014),[152] Elias et al. (2012),[153] and Pearce et al. (2008)[154] found that Indigenous respondents with a connection to residential schools have more negative health outcomes (e.g., suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and depression) than those who did not have a connection to residential schools. Additionally, Indigenous respondents with higher HLS and HLASS scores had one or more negative health outcomes.[147] While there are many studies[149][155][150][156][151] that found an association between IHT and adverse health outcomes, scholars continue to suggest that it remains difficult to understand the impact of IHT. IHT needs to be systematically measured. Indigenous people also need to be understood in separate categories based on similar experiences, location, and background as opposed to being categorized as one monolithic group.[147]

Agriculture

Plants

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples domesticated, bred, and cultivated a large array of plant species. These species now constitute between 50% and 60% of all crops in cultivation worldwide.[157] In certain cases, the Indigenous peoples developed entirely new species and strains through artificial selection, as with the domestication and breeding of maize from wild teosinte grasses in the valleys of southern Mexico. Numerous such agricultural products retain their native names in the English and Spanish lexicons.

The South American highlands became a center of early agriculture. Genetic testing of the wide variety of cultivars and wild species suggests that the potato has a single origin in the area of southern Peru,[158] from a species in the Solanum brevicaule complex. Over 99% of all modern cultivated potatoes worldwide are descendants of a subspecies Indigenous to south-central Chile,[159] Solanum tuberosum ssp. tuberosum, where it was cultivated as long as 10,000 years ago.[160][161] According to Linda Newson, "It is clear that in pre-Columbian times some groups struggled to survive and often suffered food shortages and famines, while others enjoyed a varied and substantial diet."[162]

Persistent drought around AD 850 coincided with the collapse of the Classic Maya civilization, and the famine of One Rabbit (AD 1454) was a major catastrophe in Mexico.[163]

Indigenous peoples of North America began practicing farming approximately 4,000 years ago, late in the Archaic period of North American cultures. Technology had advanced to the point where pottery had started to become common and the small-scale felling of trees had become feasible. Concurrently, the Archaic Indigenous peoples began using fire in a controlled manner. They carried out the intentional burning of vegetation to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories. It made travel easier and facilitated the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants, which were important both for food and for medicines.[164]

In the Mississippi River valley, Europeans noted that Native Americans managed groves of nut and fruit trees not far from villages and towns and their gardens and agricultural fields. They would have used prescribed burning further away, in forest and prairie areas.[165]

Many crops first domesticated by Indigenous peoples are now produced and used globally, most notably maize (or "corn") arguably the most important crop in the world.[166] Other significant crops include cassava; chia; squash (pumpkins, zucchini, marrow, acorn squash, butternut squash); the pinto bean, Phaseolus beans including most common beans, tepary beans, and lima beans; tomatoes; potatoes; sweet potatoes; avocados; peanuts; cocoa beans (used to make chocolate); vanilla; strawberries; pineapples; peppers (species and varieties of Capsicum, including bell peppers, jalapeños, paprika, and chili peppers); sunflower seeds; rubber; brazilwood; chicle; tobacco; coca; blueberries, cranberries, and some species of cotton.

Studies of contemporary Indigenous environmental management—including agro-forestry practices among Itza Maya in Guatemala and hunting and fishing among the Menominee of Wisconsin—suggest that longstanding "sacred values" may represent a summary of sustainable millennial traditions.[167]

Animals

Numerous Native American dog breeds have been used by the people of the Americas, such as the Canadian Eskimo dog, the Carolina dog, and the Chihuahua. Some indigenous peoples in the Great Plains used dogs for pulling travois, while others like the Tahltan bear dog were bred to hunt larger game. Some Andean cultures also bred the Chiribaya to herd llamas. The vast majority of dog breeds in the Americas went extinct, due to being replaced by dogs of European origin.[168]

The Fuegian dog was a domesticated variation of the culpeo that was raised by several cultures in Tierra del Fuego, like the Selk'nam and the Yahgan.[169] It was exterminated by Argentine and Chilean settlers, due to supposedly posing as a threat to livestock.[170]

Several bird species, such as turkeys, Muscovy ducks, Puna ibis, and neotropic cormorants were domesticated by various peoples in Mesoamerica and South America to be used for poultry.

In the Andean region, indigenous peoples domesticated llamas and alpacas to produce fiber and meat. The llama was the only beast of burden in the Americas before European colonization.

Guinea pigs were domesticated from wild cavies to be raised for meat consumption in the Andean region. Guinea pigs are now widely raised in Western society as household pets.

Culture

Cultural practices in the Americas seem to have been shared mostly within geographical zones where distinct ethnic groups adopt shared cultural traits, similar technologies, and social organizations. An example of such a cultural area is Mesoamerica, where millennia of coexistence and shared development among the peoples of the region produced a fairly homogeneous culture with complex agricultural and social patterns. Another well-known example is the North American plains where until the 19th century several peoples shared the traits of nomadic hunter-gatherers based primarily on bison hunting.

Languages

The languages of the North American Indians have been classified into 56 groups or stock tongues, in which the spoken languages of the tribes may be said to center. In connection with speech, reference may be made to gesture language which was highly developed in parts of this area. Of equal interest is the picture writing especially well developed among the Chippewas and Delawares.[171]

Writing systems

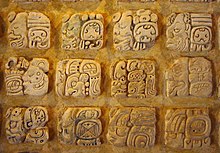

Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, pre-Columbian cultures in Mesoamerica developed several Indigenous writing systems (independent of any influence from the writing systems that existed in other parts of the world). The Cascajal Block is perhaps the earliest-known example in the Americas of what may be an extensive written text. The Olmec hieroglyphs tablet has been indirectly dated (from ceramic shards found in the same context) to approximately 900 BCE which is around the same time that the Olmec occupation of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán began to weaken.[172]

The Maya writing system was logosyllabic (a combination of phonetic syllabic symbols and logograms). It is the only pre-Columbian writing system known to have completely represented the spoken language of its community. It has more than a thousand different glyphs, but a few are variations on the same sign or have the same meaning, many appear only rarely or in particular localities, no more than about five hundred were in use in any given time, and, of those, it seems only about two hundred (including variations) represented a particular phoneme or syllable.[173][174][175]

The Zapotec writing system, one of the earliest in the Americas,[176] was logographic and presumably syllabic.[176] There are remnants of Zapotec writing in inscriptions on some of the monumental architecture of the period, but so few inscriptions are extant that it is difficult to fully describe the writing system. The oldest example of the Zapotec script, dating from around 600 BCE, is on a monument that was discovered in San José Mogote.[177]

Aztec codices (singular codex) are books that were written by pre-Columbian and colonial-era Aztecs. These codices are some of the best primary sources for descriptions of Aztec culture. The pre-Columbian codices are largely pictorial; they do not contain symbols that represent spoken or written language.[178] By contrast, colonial-era codices contain not only Aztec pictograms, but also writing that uses the Latin alphabet in several languages: Classical Nahuatl, Spanish, and occasionally Latin.

Spanish mendicants in the sixteenth century taught Indigenous scribes in their communities to write their languages using Latin letters, and there are a large number of local-level documents in Nahuatl, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Yucatec Maya from the colonial era, many of which were part of lawsuits and other legal matters. Although Spaniards initially taught Indigenous scribes alphabetic writing, the tradition became self-perpetuating at the local level.[179] The Spanish crown gathered such documentation, and contemporary Spanish translations were made for legal cases. Scholars have translated and analyzed these documents in what is called the New Philology to write histories of Indigenous peoples from Indigenous viewpoints.[180]

The Wiigwaasabak, birch bark scrolls on which the Ojibwa (Anishinaabe) people wrote complex geometrical patterns and shapes, can also be considered a form of writing, as can Mi'kmaq hieroglyphics.

Aboriginal syllabic writing, or simply syllabics, is a family of abugidas used to write some Indigenous languages of the Algonquian, Inuit, and Athabaskan language families.

Music and art

Indigenous music can vary between cultures, however, there are significant commonalities. Traditional music often centers around drumming and singing. Rattles, clapper sticks, and rasps are also popular percussive instruments, both historically and in contemporary cultures. Flutes are made of river cane, cedar, and other woods. The Apache have a type of fiddle, and fiddles are also found many First Nations and Métis cultures.

The music of the Indigenous peoples of Central Mexico and Central America, like that of the North American cultures, tends to be spiritual ceremonies. It traditionally includes a large variety of percussion and wind instruments such as drums, flutes, sea shells (used as trumpets), and "rain" tubes. No remnants of pre-Columbian stringed instruments were found until archaeologists discovered a jar in Guatemala, attributed to the Maya of the Late Classic Era (600–900 CE); this jar was decorated with imagery depicting a stringed musical instrument which has since been reproduced. This instrument is one of the very few stringed instruments known in the Americas before the introduction of European musical instruments; when played, it produces a sound that mimics a jaguar's growl.[181]

Visual arts by Indigenous peoples of the Americas comprise a major category in the world art collection. Contributions include pottery, paintings, jewelry, weavings, sculptures, basketry, carvings, and beadwork.[182] Because too many artists were posing as Native Americans and Alaska Natives[183] to profit from the cachet of Indigenous art in the United States, the U.S. passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, requiring artists to prove that they were enrolled in a state or federally recognized tribe. To support the ongoing practice of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian arts and cultures in the United States,[184] the Ford Foundation, arts advocates, and American Indian tribes created an endowment seed fund and established a national Native Arts and Cultures Foundation in 2007.[185][186]

After the entry of the Spaniards, the process of spiritual conquest was favored, among other things, by the liturgical musical service to which the natives, whose musical gifts came to surprise the missionaries, were integrated. The musical gifts of the natives were of such magnitude that they soon learned the rules of counterpoint and polyphony and even the virtuous handling of the instruments. This helped to ensure that it was not necessary to bring more musicians from Spain, which significantly annoyed the clergy.[187]

The solution that was proposed was not to employ but a certain number of indigenous people in the musical service, not to teach them counterpoint, not to allow them to play certain instruments (brass breaths, for example, in Oaxaca, Mexico) and, finally, not to import more instruments so that the indigenous people would not have access to them. The latter was not an obstacle to the musical enjoyment of the natives, who experienced the making of instruments, particularly rubbed strings (violins and double basses) or plucked (third). It is there where we can find the origin of what is now called traditional music whose instruments have their tuning and a typical Western structure.[188]

Demography

The following table provides estimates for each country in the Americas of the populations of Indigenous people and those with partial Indigenous ancestry, each expressed as a percentage of the overall population. The total percentage obtained by adding both of these categories is also given.

Note: these categories are inconsistently defined and measured differently from country to country. Some figures are based on the results of population-wide genetic surveys while others are based on self-identification or observational estimation.

| Country | Indigenous | Ref. | Part Indigenous | Ref. | Combined total | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 89% | % | 89% | [189] | |||

| 1.8% | 3.6% | 5.4% | [190] | |||

| 7% | 83% | 90% | [191] | |||

| 1.1% | 1.8% |

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Indigenous_people_of_the_Americas >Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití. Zdroj: Wikipedia.org - čítajte viac o Indigenous people of the Americas

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok. |