A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Japan |

|---|

|

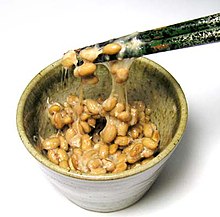

Japanese cuisine encompasses the regional and traditional foods of Japan, which have developed through centuries of political, economic, and social changes. The traditional cuisine of Japan (Japanese: washoku) is based on rice with miso soup and other dishes; there is an emphasis on seasonal ingredients. Side dishes often consist of fish, pickled vegetables, and vegetables cooked in broth. Seafood is common, often grilled, but also served raw as sashimi or in sushi. Seafood and vegetables are also deep-fried in a light batter, as tempura. Apart from rice, a staple includes noodles, such as soba and udon. Japan also has many simmered dishes, such as fish products in broth called oden, or beef in sukiyaki and nikujaga.

Historically influenced by Chinese cuisine, Japanese cuisine has also opened up to influence from Western cuisines in the modern era. Dishes inspired by foreign food—in particular Chinese food—like ramen and gyōza, as well as foods like spaghetti, curry and hamburgers, have been adapted to Japanese tastes and ingredients. Some regional dishes have also become familiar throughout Japan, including the taco rice staple of Okinawan cuisine that has itself been influenced by American and Mexican culinary traditions.[1] Traditionally, the Japanese shunned meat as a result of adherence to Buddhism, but with the modernization of Japan in the 1880s, meat-based dishes such as tonkatsu and yakiniku have become common. Since this time, Japanese cuisine, particularly sushi and ramen, has become popular globally.

In 2011, Japan overtook France to become the country with the most 3-starred Michelin restaurants; as of 2018[update], the capital of Tokyo has maintained the title of the city with the most 3-starred restaurants in the world.[2] In 2013, Japanese cuisine was added to the UNESCO Intangible Heritage List.[3]

Terminology

The word washoku (和食) is now the common word for traditional Japanese cooking. The term kappō (割烹, lit. "cutting and boiling (meats)") is synonymous with "cooking", but became a reference to mostly Japanese cooking, or restaurants, and was much used in the Meiji and Taishō eras.[4][5] It has come to connote a certain standard, perhaps even of the highest caliber, a restaurant with the most highly trained chefs.[6] However, kappō is generally seen as an eating establishment which is slightly more casual or informal compared to the kaiseki.[7]

The kaiseki (懐石, lit. "warming stone") is tied with the Japanese tea ceremony.[8] The kaiseki is considered a (simplified) form of honzen-ryōri (本膳料理, lit. "main tray cooking"),[9] which was formal banquet dining where several trays of food was served.[10] The homophone term kaiseki ryōri (会席料理, lit. "gathering + seating") originally referred to a gathering of composers of haiku or renga, and the simplified version of the honzen dishes served at the poem parties became kaiseki ryōri.[11] However, the meaning of kaiseki ryōri degenerated to become just another term for a sumptuous carousing banquet, or shuen (酒宴).[12]

Traditional cuisine

Japanese cuisine is based on combining the staple food, which is steamed white rice or gohan (御飯), with one or more okazu, "main" or "side" dishes. This may be accompanied by a clear or miso soup and tsukemono (pickles). The phrase ichijū-sansai (一汁三菜, "one soup, three sides") refers to the makeup of a typical meal served but has roots in classic kaiseki, honzen, and yūshoku cuisine. The term is also used to describe the first course served in standard kaiseki cuisine nowadays.[12]

The origin of Japanese "one soup, three sides" cuisine is a dietary style called Ichiju-Issai (一汁一菜, "one soup, one dish"),[13] tracing back to the Five Great Zen Temples of the 12-century Kamakura period (Kamakura Gozan), developed as a form of meal that emphasized frugality and simplicity.

Rice is served in its own small bowl (chawan), and each main course item is placed on its own small plate (sara) or bowl (hachi) for each individual portion. This is done even in Japanese homes. This contrasts with Western-style home dinners in which each individual takes helpings from large serving dishes of food placed in the middle of the dining table. Japanese style traditionally abhors different flavored dishes touching each other on a single plate, so different dishes are given their own individual plates as mentioned or are partitioned using, for example, leaves. Placing main dishes on top of rice, thereby "soiling" it, is also frowned upon by traditional etiquette.[14]

Although this tradition of not placing other foods on rice originated from classical Chinese dining formalities, especially after the adoption of Buddhist tea ceremonies; it became most popular and common during and after the Kamakura period, such as in the kaiseki. Although present-day Chinese cuisine has abandoned this practice, Japanese cuisine retains it. One exception is the popular donburi, in which toppings are directly served on rice.

The small rice bowl (茶碗, chawan), literally "tea bowl", doubles as a word for the large tea bowls in tea ceremonies. Thus in common speech, the drinking cup is referred to as yunomi-jawan or yunomi for the purpose of distinction. Among the nobility, each course of a full-course Japanese meal would be brought on serving napkins called zen (膳), which were originally platformed trays or small dining tables. In the modern age, faldstool trays or stackup-type legged trays may still be seen used in zashiki, i.e. tatami-mat rooms, for large banquets or at a ryokan type inn. Some restaurants might use the suffix -zen (膳) as a more sophisticated though dated synonym to the more familiar teishoku (定食), since the latter basically is a term for a combo meal served at a taishū-shokudō, akin to a diner.[15] Teishoku means a meal of fixed menu (for example, grilled fish with rice and soup), a dinner à prix fixe[16] served at shokudō (食堂, "dining hall") or ryōriten (料理店, "restaurant"), which is somewhat vague (shokudō can mean a diner-type restaurant or a corporate lunch hall); writer on Japanese popular culture Ishikawa Hiroyoshi[17] defines it as fare served at teishoku dining halls (定食食堂, teishoku-shokudō), and comparable diner-like establishments.

History

Rice is a staple in Japanese cuisine. Wheat and soybeans were introduced shortly after rice. All three act as staple foods in Japanese cuisine today. At the end of the Kofun Period and beginning of the Asuka Period, Buddhism became the official religion of the country. Therefore, eating meat and fish was prohibited. In 675 AD, Emperor Tenmu prohibited the eating of horses, dogs, monkeys, and chickens.[18] In the 8th and 9th centuries, many emperors continued to prohibit killing many types of animals. The number of regulated meats increased significantly, leading to the banning of all mammals except whale, which were categorized as fish.[19] During the Asuka period, chopsticks were introduced to Japan. Initially, they were only used by the nobility.[20] The general population used their hands, as utensils were quite expensive.

Due to the lack of meat products Japanese people minimized spice utilization. Spices were rare to find at the time. Spices like pepper and garlic were only used in a minimalist amount. In the absence of meat, fish was served as the main protein, as Japan is an island nation. Fish has influenced many iconic Japanese dishes today. In the 9th century, grilled fish and sliced raw fish were widely popular.[21] Japanese people who could afford it would eat fish at every meal; others would have to make do without animal protein for many of their meals. In traditional Japanese cuisine, oil and fat are usually avoided within the cooking process, because Japanese people were trying to keep a healthy lifestyle.[21]

Preserving fish became a sensation; sushi was originated as a means of preserving fish by fermenting it in boiled rice. Fish that are salted and then placed in rice are preserved by lactic acid fermentation, which helps prevent the proliferation of the bacteria that bring about putrefaction.[22] During the 15th century, advancement and development helped shorten the fermentation of sushi to about one to two weeks. Sushi thus became a popular snack food and main entrée, combining fish with rice. During the late Edo period (early-19th century), sushi without fermentation was introduced. Sushi was still being consumed with and without fermentation till the 19th century when the hand-rolled and nigri-type sushi was invented.[23]

In 1854, Japan started to gain new trade deals with Western countries when a new Japanese ruling order took over (known as the Meiji Restoration). Emperor Meiji, the new ruler, staged a New Years' feast designed to embrace the Western world and countries in 1872. The feast contained food that had a lot of European emphases.[citation needed] For the first time in a thousand years, people were allowed to consume meat in public. After this New Years feast, the general population from Japan started to consume meat again.[24]

Seasonality

Emphasis is placed on seasonality of food or shun (旬),[25][26] and dishes are designed to herald the arrival of the four seasons or calendar months.

Seasonality means taking advantage of the "fruit of the mountains" (山の幸, yama no sachi, alt. "bounty of the mountains") (for example, bamboo shoots in spring, chestnuts in the autumn) as well as the "fruit of the sea" (海の幸, umi no sachi, alt. "bounty of the sea") as they come into season. Thus the first catch of skipjack tunas (初鰹, hatsu-gatsuo) that arrives with the Kuroshio Current has traditionally been greatly prized.[27]

If something becomes available rather earlier than what is usual for the item in question, the first crop or early catch is called hashiri.[28]

Use of tree leaves and branches as decor is also characteristic of Japanese cuisine. Maple leaves are often floated on water to exude coolness or ryō (涼); sprigs of nandina are popularly used. The haran (Aspidistra) and sasa bamboo leaves were often cut into shapes and placed underneath or used as separators.[29]

Traditional ingredients

A characteristic of traditional Japanese food is the sparing use of red meat, oils and fats, and dairy products.[30] Use of ingredients such as soy sauce, miso, and umeboshi tends to result in dishes with high salt content, though there are low-sodium versions of these available.

Meat consumption

As Japan is an island nation surrounded by an ocean, its people have always taken advantage of the abundant seafood supply.[25] It is the opinion of some food scholars that the Japanese diet always relied mainly on "grains with vegetables or seaweeds as main, with poultry secondary, and red meat in slight amounts" even before the advent of Buddhism which placed an even stronger taboo.[25] The eating of "four-legged creatures" (四足, yotsuashi) was spoken of as taboo,[31] unclean or something to be avoided by personal choice through the Edo period.[32] The consumption of whale and terrapin meat were not forbidden under this definition. Despite this, the consumption of red meat did not completely disappear in Japan. Eating wild game—as opposed to domesticated livestock—was tolerated; in particular, trapped hare was counted using the measure word wa (羽), a term normally reserved for birds.

In 1872 of the Meiji restoration, as part of the opening up of Japan to Western influence, Emperor Meiji lifted the ban on the consumption of red meat.[33] The removal of the ban encountered resistance and in one notable response, ten monks attempted to break into the Imperial Palace. The monks asserted that due to foreign influence, large numbers of Japanese had begun eating meat and that this was "destroying the soul of the Japanese people." Several of the monks were killed during the break-in attempt, and the remainder were arrested.[33][24] On the other hand, the consumption of meat was accepted by the common people. Gyūnabe (beef hot pot), the prototype of Sukiyaki, became the rage of the time. Western restaurants moved in, and some of them changed their form to Yōshoku.

Vegetable consumption has dwindled while processed foods have become more prominent in Japanese households due to the rising costs of general foodstuffs.[34] Nonetheless, Kyoto vegetables, or Kyoyasai, are rising in popularity and different varieties of Kyoto vegetables are being revived.[35]

Cooking oil

Generally speaking, traditional Japanese cuisine is prepared with little cooking oil. A major exception is the deep-frying of foods. This cooking method was introduced during the Edo period due to influence from Western (formerly called nanban-ryōri (南蛮料理)) and Chinese cuisine,[36] and became commonplace with the availability of cooking oil due to increased productivity.[36] Dishes such as tempura, aburaage, and satsuma age[36] are now part of established traditional Japanese cuisine. Words such as tempura or hiryōzu (synonymous with ganmodoki) are said to be of Portuguese origin.

Also, certain rustic sorts of traditional Japanese foods such as kinpira, hijiki, and kiriboshi daikon usually involve stir-frying in oil before stewing in soy sauce. Some standard osōzai or obanzai dishes feature stir-fried Japanese greens with either age or chirimen-jako, dried sardines.

Seasonings

Traditional Japanese food is typically seasoned with a combination of dashi, soy sauce, sake and mirin, vinegar, sugar, and salt. A modest number of herbs and spices may be used during cooking as a hint or accent, or as a means of neutralizing fishy or gamy odors present. Examples of such spices include ginger, perilla and takanotsume (鷹の爪) red pepper.[37]

Intense condiments such as wasabi or Japanese mustard are provided as condiments to raw fish, due to their effect on the mucus membrane which paralyze the sense of smell, particularly from fish odors.[38] A sprig of mitsuba or a piece of yuzu rind floated on soups are called ukimi. Minced shiso leaves and myoga often serve as yakumi, a type of condiment paired with tataki of katsuo or soba. Shichimi is also a very popular spice mixture often added to soups, noodles and rice cakes. Shichimi is a chilli-based spice mix which contains seven spices: chilli, sansho, orange peel, black sesame, white sesame, hemp, ginger, and nori.[39]

Garnishes

Once a main dish has been cooked, spices such as minced ginger and various pungent herbs may be added as a garnish, called tsuma. Finally, a dish may be garnished with minced seaweed in the form of crumpled nori or flakes of aonori.[citation needed]

Inedible garnishes are featured in dishes to reflect a holiday or the season. Generally these include inedible leaves, flowers native to Japan or with a long history of being grown in the country, as well as their artificial counterparts.[40]

Salads

The o-hitashi or hitashi-mono (おひたし)[16] is boiled green-leaf vegetables bunched and cut to size, steeped in dashi broth,[41][42] eaten with dashes of soy sauce. Another item is sunomono (酢の物, "vinegar item"), which could be made with wakame seaweed,[43] or be something like a kōhaku namasu (紅白なます, "red white namasu")[44] made from thin toothpick slices of daikon and carrot. The so-called vinegar that is blended with the ingredient here is often sanbaizu (三杯酢, "three cupful/spoonful vinegar")[43] which is a blend of vinegar, mirin, and soy sauce. A tosazu (土佐酢, "Tosa vinegar") adds katsuo dashi to this.

An aemono (和え物) is another group of items, describable as a sort of "tossed salad" or "dressed" (though aemono also includes thin strips of squid or fish sashimi (itozukuri) etc. similarly prepared). One types are goma-ae (胡麻和え)[45] where usually vegetables such as green beans are tossed with white or black sesame seeds ground in a suribachi mortar bowl, flavored additionally with sugar and soy sauce. Shira-ae (白和え) adds tofu (bean curd) in the mix.[45] An aemono is tossed with vinegar-white miso mix and uses wakegi[45] scallion and baka-gai (バカガイ / 馬鹿貝, a trough shell, Mactra chinensis) as standard.

Cooking techniques

Different cooking techniques are applied to each of the three okazu; they may be raw (sashimi), grilled, simmered (sometimes called boiled), steamed, deep-fried, vinegared, or dressed.

Dishes

In ichijū-sansai (一汁三菜, "one soup, three sides"), the word sai (菜) has the basic meaning of "vegetable", but secondarily means any accompanying dish (whether it uses fish or meat),[46] with the more familiar combined form sōzai (惣菜),[46] which is a term for any side dish, such as the vast selections sold at Japanese supermarkets or depachikas.[47]

It figures in the Japanese word for appetizer, zensai (前菜); main dish, shusai (主菜); or sōzai (惣菜) (formal synonym for okazu), but the latter is considered somewhat of a ladies' term or nyōbō kotoba.[48]

Below are listed some of the most common categories for prepared food:

- Yakimono (焼き物), grilled and pan-fried dishes

- Nimono (煮物), stewed/simmered/cooked/boiled dishes

- Itamemono (炒め物), stir-fried dishes

- Mushimono (蒸し物), steamed dishes

- Agemono (揚げ物), deep-fried dishes

- Sashimi (刺身), sliced raw fish

- Suimono (吸い物) and shirumono (汁物), soups

- Tsukemono (漬け物), pickled/salted vegetables

- Aemono (和え物), dishes dressed with various kinds of sauce

- Sunomono (酢の物), vinegared dishes

- Chinmi (珍味), delicacies[16]

Classification

Kaiseki

Kaiseki, closely associated with tea ceremony (chanoyu), is a high form of hospitality through cuisine. The style is minimalist, extolling the aesthetics of wabi-sabi. Like the tea ceremony, appreciation of the diningware and vessels is part of the experience. In the modern standard form, the first course consists of ichijū-sansai (one soup, three dishes), followed by the serving of sake accompanied by dish(es) plated on a square wooden bordered tray of sorts called hassun (八寸). Sometimes another element called shiizakana (強肴) is served to complement the sake, for guests who are heavier drinkers.

Vegetarian

Strictly vegetarian food is rare since even vegetable dishes are flavored with the ubiquitous dashi stock, usually made with katsuobushi (dried skipjack tuna flakes), and are therefore pescetarian more often than carnivorous. An exception is shōjin-ryōri (精進料理), vegetarian dishes developed by Buddhist monks. However, the advertised shōjin-ryōri at public eating places includes some non-vegetarian elements. Vegetarianism, fucha-ryōri (普茶料理) was introduced from China by the Ōbaku sect (a sub-sect of Zen Buddhism), and which some sources still regard as part of "Japanese cuisine".[25] The sect in Japan was founded by the priest Ingen (d. 1673), and is headquartered in Uji, Kyoto. The Japanese name for the common green bean takes after this priest who allegedly introduced the New World crop via China. One aspect of the fucha-ryōri practiced at the temple is the wealth of modoki-ryōri (もどき料理, "mock foods"), one example being mock-eel, made from strained tofu, with nori seaweed used expertly to mimic the black skin.[49] The secret ingredient used is grated gobō (burdock) roots.[50][51]

Masakazu Tada, Honorary Vice-President of the International Vegetarian Union for 25 years from 1960, stated that "Japan was vegetarian for 1,000 years". The taboo against eating meat was lifted in 1872 by the Meiji Emperor as part of an effort towards westernizing Japan.[24] British journalist J. W. Robertson Scott reported in the 1920s that the society was still 90% vegetarian, and 50–60% of the population ate fish only on festive occasions, probably due to poverty more than for any other reason.

Rice

Rice has historically been the staple food of the Japanese people. Its fundamental importance is evident from the fact that the word for cooked rice, gohan or meshi, also stands for a "meal".[52] While rice has an ancient history of cultivation in Japan, its use as a staple has not been universal. Notably, in northern areas (northern Honshū and Hokkaidō), other grains such as wheat were more common into the 19th century.

In most of Japan, rice used to be consumed for almost every meal, and although a 2007 survey showed that 70% of Japanese still eat it once or twice a day, its popularity is now declining. In the 20th century there has been a shift in dietary habits, with an increasing number of people choosing wheat-based products (such as bread and noodles) over rice.[53]

Japanese rice is short-grained and becomes sticky when cooked. Most rice is sold as hakumai (白米, "white rice"), with the outer portion of the grains (糠, nuka) polished away. Unpolished brown rice (玄米, genmai) is considered less desirable, but its popularity has been increasing.[53]

Noodles

Japanese noodles often substitute for a rice-based meal. Soba (thin, grayish-brown noodles containing buckwheat flour) and udon (thick wheat noodles) are the main traditional noodles, while ramen is a modern import and now very popular. There are also other, less common noodles, such as somen (thin, white noodles containing wheat flour).

Japanese noodles, such as soba and udon, are eaten as a standalone, and usually not with a side dish, in terms of general custom. It may have toppings, but they are called gu (具). The fried battered shrimp tempura sitting in a bowl of tempura-soba would be referred to as "the shrimp" or "the tempura", and not so much be referred to as a topping (gu). The identical toppings, if served as a dish to be eaten with plain white rice could be called okazu, so these terms are context-sensitive. Some noodle dishes derive their name from Japanese folklore, such as kitsune and tanuki, reflecting dishes in which the noodles can be changed, but the broth and garnishes correspond to their respective legend.[54]

Hot noodles are usually served in a bowl already steeped in their broth and are called kakesoba or kakeudon. Cold soba arrive unseasoned and heaped atop a zaru or seiro, and are picked up with a chopstick and dunked in their dip sauce. The broth is a soy-dashi-mirin type of mix; the dip is similar but more concentrated (heavier on soy sauce).

In the simple form, yakumi (condiments and spices) such as shichimi, nori, finely chopped scallions, wasabi, etc. are added to the noodles, besides the broth/dip sauce.

Udon may also be eaten in kama-age style, piping hot straight out of the boiling pot, and eaten with plain soy sauce and sometimes with raw egg also.

Japanese noodles are traditionally eaten by bringing the bowl close to the mouth, and sucking in the noodles with the aid of chopsticks. The resulting loud slurping noise is considered normal in Japan, although in the 2010s concerns began to be voiced about the slurping being offensive to others, especially tourists. The word nuuhara (ヌーハラ, from "nuudoru harasumento", noodle harassment) was coined to describe this.[55]

Sweets

Traditional Japanese sweets are known as wagashi. Ingredients such as red bean paste and mochi are used. More modern-day tastes includes green tea ice cream, a very popular flavor. Almost all manufacturers produce a version of it. Kakigōri is a shaved ice dessert flavored with syrup or condensed milk. It is usually sold and eaten at summer festivals. A dessert very popular amongst children in Japan is dorayaki. They are sweet pancakes filled with a sweet red bean paste. They are mostly eaten at room temperature but are also considered very delicious hot.

Beverages

Tea

Green tea may be served with most Japanese dishes. It is produced in Japan and prepared in various forms such as matcha, the tea used in the Japanese tea ceremony.[56]

Beer

Beer production started in Japan in the 1860s. The most commonly consumed beers in Japan are pale-colored light lagers, with an alcohol strength of around 5.0% ABV. Lager beers are the most commonly produced beer style in Japan, but beer-like beverages, made with lower levels of malts called Happoshu (発泡酒, literally, "bubbly alcohol") or non-malt Happousei (発泡性, literally "effervescence") have captured a large part of the market as tax is substantially lower on these products. Beer and its varieties have a market share of almost 2/3 of alcoholic beverages.

Small local microbreweries have also gained increasing popularity since the 1990s, supplying distinct tasting beers in a variety of styles that seek to match the emphasis on craftsmanship, quality, and ingredient provenance often associated with Japanese food.

Sake

Sake is a brewed rice beverage that typically contains 15–17% alcohol and is made by multiple fermentation of rice. At traditional formal meals, it is considered an equivalent to rice and is not simultaneously taken with other rice-based dishes, although this notion is typically no longer applied to modern, refined, premium ("ginjo") sake, which bear little resemblance to the sakes of even 100 years ago. Side dishes for sake are particularly called sakana or otsumami.

Sake is brewed in a highly labor-intensive process more similar to beer production than winemaking, hence, the common description of sake as rice "wine" is misleading.

Sake is made with, by legal definition, strictly just four ingredients: special rice, water, koji, and special yeast.

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Japanese_cuisine

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.