A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

An Islamic garden is generally an expressive estate of land that includes themes of water and shade. Their most identifiable architectural design reflects the charbagh (or chahār bāgh) quadrilateral layout with four smaller gardens divided by walkways or flowing water. Unlike English gardens, which are often designed for walking, Islamic gardens are intended for rest, reflection, and contemplation. A major focus of the Islamic gardens was to provide a sensory experience, which was accomplished through the use of water and aromatic plants.

Before Islam had expanded to other climates, these gardens were historically used to provide respite from a hot and arid environment. They encompassed a wide variety of forms and purposes which no longer exist. The Qur'an has many references to gardens and states that gardens are used as an earthly analogue for the life in paradise which is promised to believers:

Allah has promised to the believing men and the believing women gardens, beneath which rivers flow, to abide in them, and goodly dwellings in gardens of perpetual abode; and best of all is Allah's goodly pleasure; that is the grand achievement. – Qur'an 9.72

Along with the popular paradisiacal interpretation of gardens, there are several other non-pious associations with Islamic gardens including wealth, power, territory, pleasure, hunting, leisure, love, and time and space. These other associations provide more symbolism in the manner of serene thoughts and reflection and are associated with a scholarly sense.

While many Islamic gardens no longer exist, scholars have inferred much about them from Arabic and Persian literature on the subject. Numerous formal Islamic gardens have survived in a wide zone extending from Spain and Morocco in the west to India in the east. [1]Historians disagree as to which gardens ought to be considered part of the Islamic garden tradition, which has influenced three continents over several centuries.

Architectural design and influences

After the Arab invasions of the 7th century CE, the traditional design of the Persian garden was used in many Islamic gardens. Persian gardens were traditionally enclosed by walls and the Persian word for an enclosed space is pairi-daeza, leading to the paradise garden.[2] Hellenistic influences are also apparent in their design, as seen in the use of straight lines in a few garden plans that are also blended with Sassanid ornamental plantations and fountains.[3]

One of the most identifiable garden designs, known as the charbagh (or chahār bāgh), consists of four quadrants most commonly divided by either water channels or walkways, that took on many forms.[4] One of these variations included sunken quadrants with planted trees filling them, so that they would be level to the viewer.[4] Another variation is a courtyard at the center intersection, with pools built either in the courtyard or surrounding the courtyard.[4] While the charbagh gardens are the most identified gardens, very few were actually built, possibly due to their high costs or because they belonged to the higher class, who had the capabilities to ensure their survival.[4] Notable examples of the charbagh include the former Bulkawara Palace in Samarra, Iraq,[5] and Madinat al-Zahra near Córdoba, Spain.[6]

An interpretation of the charbagh design is conveyed as a metaphor for a "whirling wheel of time" that challenges time and change.[7] This idea of cyclical time places man at the center of this wheel or space and reinforces perpetual renewal and the idea that the garden represents the antithesis of deterioration.[7] The enclosed garden forms a space that is permanent, a space where time does not decay the elements within the walls, representing an unworldly domain.[7] At the center of the cycle of time is the human being who, after being released, eventually reaches eternity.[7]

Aside from gardens typically found in palaces, they also found their way into other locations. The Great Mosque of Córdoba contains a continuously planted garden in which rows of fruit trees, similar to an orchard, were planted in the courtyard.[4] This garden was irrigated by a nearby aqueduct and served to provide shade and possibly fruit for the mosque's caretaker.[4] Another type of garden design includes stepped terraces, in which water flows through a central axis, creating a trickling sound and animation effect with each step, which could also be used to power water jets.[4] Examples of the stepped terrace gardens include the Shālamār Bāgh, the Bāgh-i Bābur, and Madinat al-Zahra.[4]

Elements

Islamic gardens present a variety of devices that contribute to the stimulation of several senses and the mind, to enhance a person's experience within the garden. These devices include the manipulation of water and the use of aromatic plants.[8]

Arabic and Persian literature reflect how people historically interacted with Islamic gardens. The gardens' worldly embodiment of paradise provided the space for poets to contemplate the nature and beauty of life. Water is the most prevalent motif in Islamic garden poetry, as poets render water as semi-precious stones and features of their beloved women or men.[9] Poets also engaged multiple sensations to interpret the dematerialized nature of the garden. Sounds, sights, and scents in the garden led poets to transcend the dry climate in desert-like locations.[10] Classical literature and poetry on the subject allow scholars to investigate the cultural significance of water and plants, which embody religious, symbolic, and practical qualities.

Water

Water was an integral part of the landscape architecture and served many sensory functions, such as a desire for interaction, illusionary reflections, and animation of still objects, thereby stimulating visual, auditory and somatosensory senses. The centrally placed pools and fountains in Islamic gardens remind visitors of the essence of water in the Islamic world.

Islam emerged in the desert, and the thirst and gratitude for water are embedded in its nature. In the Qur'an, rivers are the primary constituents of the paradise, and references to rain and fountains abound. Water is the materia prima of the Islamic world, as stated in the Qur'an 31:30: "God preferred water over any other created thing and made it the basis of creation, as He said: 'And We made every living thing of water'." Water embodies the virtues God expects from His subjects. "Then the water was told, 'Be still'. And it was still, awaiting God's command. This is implied water, which contains neither impurity nor foam" (Tales of the Prophets, al-Kisa'). Examining their reflections in the water allows the faithful to integrate the water's stillness and purity, and the religious implication of water sets the undertone for the experience of being in an Islamic garden.[10]

Based on the spiritual experience, water serves as the means of physical and emotional cleansing and refreshment. Due to the hot and arid conditions where gardens were often built, water was used as a way to refresh, cleanse, and cool an exhausted visitor. Therefore, many people would come to the gardens solely to interact with the water.[2]

Reflecting pools were strategically placed to reflect the building structures, interconnecting the exterior and interior spaces.[8] The reflection created an illusion that enlarged the building and doubled the effect of solemnity and formality. The effect of rippling water from jets and shimmering sunlight further emphasized the reflection.[8] In general, mirroring the surrounding structures combined with the vegetation and the sky creates a visual effect that expands the enclosed space of a garden. Given the water's direct connection to paradise, its illusionary effects contribute to a visitor's spiritual experience.

Another use of water was to provide kinetic motion and sound to the stillness of a walled garden,[8] enlivening the imposing atmosphere. Fountains, called salsabil fountains for "the fountain in the paradise" in Arabic, are prevalent in medieval Islamic palaces and residences. Unlike the pools that manifest stillness, these structures demonstrate the movement of water, yet celebrate the solidity of water as it runs through narrow channels extending from the basin.[10]

In the Alhambra Palace, around the rim of the basin of the Fountain of the Lions, the admiration for the water's virtue is inscribed: "Silver melting which flows between jewels, one like the other in beauty, white in purity; a running stream evokes the illusion of a solid substance; for the eyes, so that we wonder which one is fluid. Don't you see that it is the water that is running over the rim of the fountain, whereas it is the structure that offers channels for the water flow."[9] By rendering the streams of water melting silver, the poem implies that though the fountain creates dynamics, the water flowing in the narrow channels allow the structure to blend into the solemn architectural style as opposed to disrupting the harmony. Many Nasrid palaces included a sculpture in their garden in which a jet of water would flow out of the structure's mouth, adding motion and a "roaring sound" of water to the garden.[8]

As the central component of Islamic architecture, water incorporates the religious implications and contributes to the spiritual, bodily and emotional experience that visitors could hardly acquire from the outside world.

Sensory plants

Irrigation and fertile soil were used to support a botanical variety which could not otherwise exist in a dry climate.[11] Many of the extant gardens do not contain the same vegetation as when they were first created, due to the lack of botanical accuracy in written texts. Historical texts tended to focus on the sensory experience, rather than details of the agriculture.[12] There is, however, record of various fruit-bearing trees and flowers that contributed to the aromatic aspect of the garden, such as cherries, peaches, almonds, jasmine, roses, narcissi, violets, and lilies.[2] According to the medico-botanical literature, many plants in the Islamic garden produce therapeutic and erotic aromatics.

Muslim scientist al-Ghazzi, who believed in the healing powers of nature, experimented with medicinal plants and wrote extensively on scented plants.[13] A garden retreat was often a "royal" prescription for treating headaches and fevers. The patient was advised to "remain in cool areas, surrounded by plants that have cooling effects such as sandalwood trees and camphor trees."[14]

Yunani medicine explains the role of scent as a mood booster, describing scent as "the food of the spirit". Scent enhances one's perceptions,[15] stirs memories, and makes the experience of visiting the garden more personal and intimate. Islamic medico-botanical literature suggests the erotic nature of some aromatic plants, and medieval Muslim poets note the role of scents in love games. Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah reflects the scents worn by lovers to attract each other, and the presence of aromatic bouquets that provides sensual pleasures in garden spaces.[16]

Exotic plants were also sought by royalty for their exclusivity as status symbols, to signify the power and wealth of the country.[17] Examples of exotic plants found in royal gardens include pomegranates, Dunaqāl figs, a variety of pears, bananas, sugar cane and apples, which provided a rare taste.[17] By the tenth century, the royal gardens of the Umayyads at Cordova were at the forefront of botanical gardens, experimenting with seeds, cuttings, and roots brought from the outermost reaches of the known world.[18]

Dematerialization

The wide variety and forms of devices used in structuring the gardens provide inconsistent experiences for the viewer, and contribute to the garden's dematerialization.[clarification needed][8] The irregular flow of water and the angles of sunlight were the primary tools used to create a mysterious experience in the garden.[8] Many aspects of gardens were also introduced inside buildings and structures to contribute to the building's dematerialization. Water channels were often drawn into rooms that overlooked lush gardens and agriculture so that gardens and architecture would be intertwined and indistinguishable, deemphasizing a human's role in the creation of the structure.[19]

Symbolism

Paradise

Islamic gardens carry several associations of purpose beyond their common religious symbolism.[20] Most Islamic gardens are typically thought to represent paradise. In particular, gardens that encompassed a mausoleum or tomb were intended to evoke the literal paradise of the afterlife.[21]

For the gardens that were intended to represent paradise, there were common themes of life and death present, such as flowers that would bloom and die, representing a human's life.[19] Along with flowers, other agriculture such as fruit trees were included in gardens that surrounded mausoleums.[22] These fruit trees, along with areas of shade and cooling water, were added because it was believed that the souls of the deceased could enjoy them in the afterlife.[22] Fountains, often found in the center of the gardens, were used to represent paradise and were most commonly octagonal, which is geometrically inclusive of a square and a circle.[2] In this octagonal design, the square was representative of the earth, while the circle represented heaven, therefore its geometric design was intended to represent the gates of heaven; the transition between earth and heaven.[2] The color green was also a very prominent tool in this religious symbolism, as green is the color of Islam, and a majority of the foliage, aside from flowers, expressed this color.[2]

Religious references

Gardens are mentioned in the Qur'an to represent a vision of paradise. It states that believers will dwell in "gardens, beneath which rivers flow" (Qur'an 9:72). The Qur'an mentions paradise as containing four rivers: honey, wine, water, and milk; this has led to a common misinterpreted association of the charbagh design's four axial water channels solely with paradise.[23]

Images of paradise abound in poetry. The ancient king Iram, who attempted to rival paradise by building the "Garden of Iram" in his kingdom, captured the imagination of poets in the Islamic world.[relevant?] The description of gardens in poetry provides the archetypal garden of paradise. Pre-Islamic and Umayyad cultures imagined serene and rich gardens of paradise that provided an oasis in the arid environment in which they often lived.[6] A Persian garden, based on the Zoroastrian myth, is a prototype of the garden of water and plants. Water is also an essential aspect of this paradise for the righteous.[6] The water in the garden represents Kausar, the sacred lake in paradise, and only the righteous deserve to drink. Water represents God's benevolence to his people, a necessity for survival.[6] Rain and water are also closely associated with God's mercy in the Qur'an.[2] Conversely, water can be seen as a punishment from God through floods and other natural disasters.[6]

The use of a garden as a metaphor is well established in Deccani literature, with an unkempt garden representing a world in disarray and a "garden of love" suggesting fulfilment and harmony.[24] The Deccani poem Gulshan-i 'Ishq ("Rose Garden of Love"), written by Nusrati in 1657, describes a succession of natural scenes,[24] culminating in a rose garden that serves as a poetic metaphor for spiritual and romantic union.[25]

The four squares of the charbagh refer to the Islamic aspect of universe: that the universe is composed of four different parts. The four dividing water channels symbolize the four rivers in paradise. The gardener is the earthly reflection of Rizvan, the gardener of Paradise. Of the trees in Islamic gardens, "chinar" refers to the Ṭūbā tree that grows in heaven. The image of the Tuba tree is also commonly found on the mosaic and mural of Islamic architecture. In Zoroastrian myth, Chinar is the holy tree which is brought to Earth from heaven by the prophet Zoroaster.

Status symbols

Islamic gardens were often used to convey a sense of power and wealth among its patrons. The magnificent size of palace gardens directly showed an individual's financial capabilities and sovereignty while overwhelming their audiences.[6] The palaces and gardens built in Samarra, Iraq, were massive in size, demonstrating the magnificence of the Abbasid Caliphate.[6]

To convey royal power, parallels are implied to connect the "garden of paradise" and "garden of the king". The ability to regulate water demonstrated the ruler's power and wealth associated with irrigation. The ruling caliph had control over the water supply, which was necessary for gardens to flourish, making it understood that owning a large functioning garden required a great deal of power.[6] Rulers and wealthy elite often entertained their guests on their garden properties near water, demonstrating the luxury that came with such an abundance of water.[6] The light reflected by water was believed to be a blessing upon the ruler's reign.[6] In addition, the well-divided garden implies the ruler's mastery over their environment.

Several palace gardens, including Hayr al-Wuhush in Samarra, Iraq, were used as game preserves and places to hunt.[26] The sheer size of the hunting enclosures reinforced the power and wealth of the caliph.[6] A major idea of the 'princely cycle' was hunting, in which it was noble to partake in the activity and showed greatness.[26]

Variations of design

Many of the gardens of Islamic civilization no longer exist today. While most extant gardens retain their forms, they had not been continually tended and the original plantings have been replaced with contemporary plants.[27] A transient form of architectural art, gardens fluctuate due to the climate and the resources available for their care. The most affluent gardens required considerable resources by design, and their upkeep could not be maintained across eras. A lack of botanical accuracy in the historical record has made it impossible to properly restore the agriculture to its original state.[12]

There is debate among historians as to which gardens ought to be considered part of the Islamic garden tradition, since it spans Asia, Europe, and Africa over centuries.[28]

Umayyad gardens

Al-Ruṣāfa, near the village of the same name in present-day northern Syria, was a palace with an enclosed garden at the country estate of Umayyad caliph Hishām I. It had a stone pavilion in the center with arcades surrounding the pavilion. It is believed to be the earliest example of a formal charbagh design.[12]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Islamic_garden

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

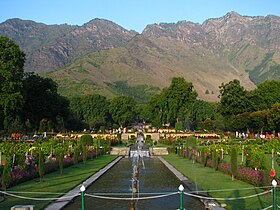

Nishat Bagh

Mughal gardens

Category:Arab culture

Arab culture

File:Syrischer Maler von 1222 001.jpg

Category:Arabic architecture

Islamic architecture

Architecture of Yemen

Nabataean architecture

Umayyad architecture

Abbasid architecture

Fatimid architecture

Moorish architecture

Mamluk architecture

Ablaq

Alfiz

Arabesque

History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

Banna'i

Girih

Horseshoe arch

Howz

Hypostyle

Islamic calligraphy

Islamic geometric patterns

Islamic ornament

Iwan

Liwan

Mashrabiya

Riad (architecture)

Mosaic#Arab

Multifoil arch

Muqarnas

Nagash painting

Qadad

Reflecting pool

Riwaq (arcade)

Sahn

Socarrat

Stucco decoration in Islamic architecture

Tadelakt

Vaulting

Voussoir

Windcatcher

Zellij

Albarrana tower

Alcázar

Bazaar

Caravanserai

Bimaristan

Hammam

Kasbah

Madrasa

Maqam (shrine)

Mazar (mausoleum)

Mosque

Medina quarter

Qalat (fortress)

Ribat

Sebil

Shadirvan

Tekyeh

Well house

Zawiya (institution)

Category:Arabic art

Ancient South Arabian art

Nabataean art

Islamic art

Fatimid art

Mamluk Sultanate#Art

Arabic calligraphy

Islamic graffiti

Arab carpet

Arabic miniature

Category:Arabic pottery

Olive wood carving in Palestine

Islamic embroidery

Hardstone carving#Islamic hardstone carving

Islamic glass

Ivory carving#Islamic ivory

Islamic art#Islamic brasswork

Arabesque (Islamic art)

Arabic geometric patterns

Banna'i

Damascus steel

Damask

Girih tiles

Hedwig glass

Kiswah

Muqarnas

Pseudo-Arabic

Zellij

Arab cuisine

Eastern Arabian cuisine

Levantine cuisine

Iraqi cuisine

Egyptian cuisine

Sudanese cuisine

Maghreb cuisine

Category:Arabic clothing

Agal (accessory)

Battoulah

Haik (garment)

Keffiyeh

Litham

Madhalla

Taqiyah (cap)

Tantour

Fez (hat)

Turban

Abaya

Bisht (clothing)

Burnous

Djellaba

Durra'ah

Fouta towel

Izaar

Jellabiya

Kaftan

Sarong#Somalia

Robe of honour

Sirwal

Takchita

Thawb

Tiraz

Arabic music

Arabic maqam

Arab tone system

Algerian scale

Rhythm in Arabic music

Taqsim

Jins

Lazma

Teslim

Quarter tone

Category:Arabic musical instruments

Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir

Kitab al-Aghani

Arabic pop

Arabic hip hop

Arabic rock

Arabic music#Arabic jazz

Arabic music#20th century

Opera in Arabic

Al Jeel

Khaliji (music)

Raï

Andalusian classical music

Andalusi nubah

Bashraf

Dawr

Dulab

Layali

Malhun

Iraqi maqam

Mawwal

Muwashshah

Qasidah

Qudud Halabiya

Sama'i

Tahmilah

Taqsim

Waslah

Ataaba

Raï

Bedouin music

Chaabi (Algeria)

Chaabi (Morocco)

Baladi

Fann at-Tanbura

Fijiri

Gnawa music

Liwa (music)

Mawwal

Mezwed

Samri

Sawt (music)

Shaabi

Zajal

Arab dance

Ardah

Belly dance

Dabke

Arab dance#Deheyeh

Arab dance#Guedra

Arab dance#Hagallah

Khaleegy (dance)

Liwa (music)

Mizmar (dance)

Ouled Nail

Raqs Sharqi

Samri

Arab dance#Shamadan

Arab dance#Schikhatt

Tahtib

Sufi whirling#Egyptian tanoura

Yowlah

Zār

Arabic literature

Arabic

Old Arabic

Paleo-Arabic

Classical Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic

Arabic epic literature

Rhymed prose

Maqama

Category:Arabic erotic literature

Category:Arabic grimoires

Literary criticism#Classical and medieval criticism

Arabic short story

Tabaqat

Tezkire

Rihla

Category:Islamic mirrors for princes

Islamic literature

Quran

Tafsir

Hadith

Sīra

Fiqh

Aqidah

Poetry

Category:Arabic anthologies

Category:Arabic-language poets

Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry

Modern Arabic poetry

Hija

Rithā'

Waṣf

Ghazal

Hamasah

Diwan (poetry)

Qasida

Muwashshah

Rajaz (prosody)

Mathnawi

Ruba'i

Nasīb (poetry)

Riddles (Arabic)

Kharja

Zajal

Mawwal

Nabati

Ghinnawa

Arabic prosody

Bayt (poetry)

Ṭawīl

Basīṭ

Kamil (metre)

Wāfir

Hazaj meter

Rajaz

Arabic literature

Algerian literature

Literature of Bahrain

Comoros

Literature of Djibouti

Egyptian literature

Iraqi literature

Culture of Jordan

Kuwaiti literature

Culture of Lebanon

Libyan literature

Mauritania

Moroccan literature

Culture of Oman

Palestinian literature

Qatari literature

List of Saudi Arabian writers

Somali literature

Sudanese literature

Syrian literature

Tunisian literature

Culture of the United Arab Emirates

Culture of Yemen

Arabic science

Arabic alchemy

Arabic astrology

Arabic astronomy

Islamic geography

Islamic Golden Age

Islamic mathematics

Islamic medicine

Islamic psychology

Islamic technology

Arabic philosophy

Early Islamic philosophy

Aristotelianism#Islamic world

Platonism in Islamic Philosophy

Logic in Islamic philosophy

Kalam

Sufi metaphysics

Sufi philosophy

Al-Farabi

Avicennism

Averroism

Al-aql al-faal

Aql bi-l-fi'l

Al-Insān al-Kāmil

Dhati in islamic philosophy

Peace in Islamic philosophy

Arcs of Descent and Ascent

Asabiyyah

Hal (Sufism)

Irfan

Nafs

Qadar

Qalb

Liber de Causis

The Theology of Aristotle

Al-isharat wa al-tanbihat

The Book of the Apple

Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity

The Incoherence of the Philosophers

The Incoherence of the Incoherence

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

Theologus Autodidactus

Updating...x

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.