A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (February 2024) |

Republic of Somaliland | |

|---|---|

| Motto: لا إله إلا الله محمد رسول الله Lā ilāhā illā-llāhu; muḥammadun rasūlu-llāh "There is no God but Allah; Muhammad is the Messenger of God" | |

| Anthem: Samo ku waar حياة طويلة مع السلام "Live in Eternal Peace" | |

Territory controlled Territory disputed | |

| Status | Unrecognised state; recognised by the United Nations as de jure part of Somalia |

| Capital and largest city | Hargeisa 9°33′N 44°03′E / 9.550°N 44.050°E |

| Official languages | Somali |

| Second language | Arabic,[1] English |

| Religion | Islam (official) |

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Muse Bihi Abdi | |

| Abdirahman Saylici | |

| Yasin Haji Mohamoud | |

| Adan Haji Ali | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| House of Elders | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| c. 2500 BCE | |

| 1185 | |

| 1750–1884 | |

• Establishment of British protectorate | 1884 |

| 26 June 1960[1] | |

• Union with the Trust Territory of Somaliland | 1 July 1960[1] |

| 18 May 1991[1] | |

| 13 June 2001 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 177,000[3] km2 (68,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 5.7 million[4] (114th) |

• Density | 28.27[3]/km2 (73.2/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | $3.782 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $852[5] |

| Currency | Somaliland shilling |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Date format | d/m/yy (AD) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +252 (Somalia) |

Somaliland, officially the Republic of Somaliland, is an unrecognised state in the Horn of Africa, recognised internationally as de jure part of Somalia.[6][7][8] It is located in the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden and bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, Ethiopia to the south and west, and Somalia to the east.[9][10][11][12] Its claimed territory has an area of 176,120 square kilometres (68,000 sq mi),[13] with approximately 5.7 million residents as of 2021.[14][15] The capital and largest city is Hargeisa. The Government of Somaliland regards itself as the successor state to British Somaliland, which, as the briefly independent State of Somaliland, united from 1960 to 1991 with the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland) to form the Somali Republic.[16]

Since 1991, the territory has been governed by democratically-elected governments that seek international recognition as the government of the Republic of Somaliland.[17][18][19][20] The central government maintains informal ties with some foreign governments, who have sent delegations to Hargeisa;[21][22][23] Somaliland hosts representative offices from several countries, including Ethiopia and Taiwan.[24][25] However, Somaliland's self-proclaimed independence has not been officially recognised by any UN member state or international organisation.[21][26][27] It is the largest unrecognised state in the world by de facto controlled land area. It is a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization, an advocacy group whose members consist of indigenous peoples, minorities and unrecognised or occupied territories.[28]

Etymology

The name Somaliland is derived from two words: "Somali" and "land". The area was named when Britain took control from the Egyptian administration in 1884, after signing successive treaties with the ruling Somali Sultans from the Isaaq, Issa, Gadabursi, and Warsangali clans. The British established a protectorate in the region referred to as British Somaliland. In 1960, when the protectorate became independent from Britain, it was called State of Somaliland. Five days later, on 1 July 1960, Somaliland united with Italian Somaliland. The name "Republic of Somaliland" was adopted upon the declaration of independence following the Somali Civil War in 1991.[29]

At the Grand conference in Burao held in 1991 many names for the country were suggested, including Puntland, in reference to Somaliland's location in the ancient Land of Punt and which is now the name of the Puntland state in neighbouring Somalia, and Shankaroon, meaning "better than five" in Somali, in reference to the five regions of Greater Somalia.[30]

History

Prehistory

The area of Somaliland was inhabited around 10,000 years ago during the Neolithic age.[31][32] The ancient shepherds raised cows and other livestock and created vibrant rock art paintings. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here.[33] The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somaliland dating back to the 4th millennium BCE.[34] The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterised in 1909 as important artefacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.[35]

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[36] or the Near East.[37]

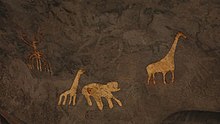

The Laas Geel complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa dates back around 5,000 years, and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows.[38] Other cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the distinctive Ethiopian-Arabian style, dated to 1,000 to 3,000 BCE.[39][40] Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in eastern Somaliland lies Karinhegane, the site of numerous cave paintings of real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.[41][42]

Antiquity and classical era

Ancient pyramidical structures, mausoleums, ruined cities and stone walls, such as the Wargaade Wall, are evidence of civilisations thriving in the Somali peninsula.[43][44] Ancient Somaliland had a trading relationship with ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece dating back to at least the second millennium BCE, supporting the hypothesis that Somalia or adjacent regions were the location of the ancient Land of Punt.[43][45] The Puntites traded myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense with the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Chinese and Romans through their commercial ports. An Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati.[43] In 2015, isotopic analysis of ancient baboon mummies from Punt that had been brought to Egypt as gifts indicated that the specimens likely originated from an area encompassing eastern Somalia and the Eritrea-Ethiopia corridor.[46]

The camel is believed to have been domesticated in the Horn region sometime between the 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE. From there, it spread to Egypt and the Maghreb.[47] During the classical period, the northern Barbara city-states of Mosylon, Opone, Mundus, Isis, Malao, Avalites, Essina, Nikon, and Sarapion developed a lucrative trade network, connecting with merchants from Ptolemaic Egypt, Ancient Greece, Phoenicia, Parthian Persia, Saba, the Nabataean Kingdom, and the Roman Empire. They used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.[48]

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the establishment of a Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants cooperated with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula[49] to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.[50] However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference.[51]

For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from Ceylon and the Spice Islands. The source of the spices is said to have been the best-kept secret of Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world; the Romans and Greeks believed the source to have been the Somali peninsula.[52] The collaboration between Somali and Arab traders inflated the price of Indian and Chinese cinnamon in North Africa, the Near East, and Europe, and made the spice trade profitable, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands large quantities were shipped across sea and land routes.[50]

In 2007, more rock art sites with Sabaean and Himyarite writings in and around Hargeisa were found, but some were bulldozed by developers.[53]

Birth of Islam and the Middle Ages

Various Somali Muslim kingdoms were established in the area in the early Islamic period.[54] In the 14th century, the Zeila-based Adal Sultanate battled the forces of the Ethiopian emperor Amda Seyon I.[55] The Ottoman Empire later occupied Berbera and environs in the 1500s. Muhammad Ali, Pasha of Egypt, subsequently established a foothold in the area between 1821 and 1841.[56]

The Sanaag region is home to the ruined Islamic city of Maduna near El Afweyn, which is considered the most substantial and accessible ruin of its type in Somaliland.[57][58] The main feature of the ruined city is a large rectangular mosque, its 3 metre high walls still standing, which include a mihrab and possibly several smaller arched niches.[58] Swedish-Somali archaeologist Sada Mire dates the ruined city to the 15th–17th centuries.[59]

Early modern sultanates

Isaaq Sultanate

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate began to flourish in Somaliland. These included the Isaaq Sultanate and Habr Yunis Sultanate.[60] The Isaaq Sultanate was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. It spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan, descendants of the Banu Hashim clan,[61] in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch established by the first sultan, Sultan Guled Abdi, of the Eidagale clan. The sultanate is the pre-colonial predecessor to the modern Republic of Somaliland.[62][63][64]

According to oral tradition, prior to the Guled dynasty the Isaaq clan-family were ruled by a dynasty of the Tolje'lo branch descending from Ahmed nicknamed Tol Je'lo, the eldest son of Sheikh Ishaaq's Harari wife. There were eight Tolje'lo rulers in total, starting with Boqor Harun (Somali: Boqor Haaruun) who ruled the Isaaq Sultanate for centuries starting from the 13th century.[65][66] The last Tolje'lo ruler Garad Dhuh Barar (Somali: Dhuux Baraar) was overthrown by a coalition of Isaaq clans. The once strong Tolje'lo clan were scattered and took refuge amongst the Habr Awal with whom they still mostly live.[67][68]

The Sultan of Isaaq regularly convened shirs (meetings) where he would be informed and advised by leading elders or religious figures on what decisions to make. In the case of the Dervish movement, Sultan Deria Hassan had chosen not to join after receiving counsel from Sheikh Madar. He addressed early tensions between the Saad Musa and Eidagale upon the former's settlement into the growing town of Hargeisa in the late 19th century.[69] The Sultan was also responsible for organising grazing rights and, in the late 19th century, new agricultural spaces.[70] The allocation of resources and sustainable use of them was also a matter that Sultans concerned themselves with and was crucial in this arid region. In the 1870s, at a famous meeting between Sheikh Madar and Sultan Deria, it was proclaimed that hunting and tree cutting in the vicinity of Hargeisa would be banned,[71] and that the holy relics from Aw Barkhadle would be brought and oaths would be sworn on them by the Isaaqs in the presence of the Sultan whenever internal combat broke out.[72]

Aside from the leading Sultan of Isaaq there were numerous Akils, Garaads and subordinate Sultans alongside religious authorities that constituted the Sultanate; occasionally these would declare their independence or simply break from its authority.

The Isaaq Sultanate had 5 rulers prior to the creation of British Somaliland in 1884. Historically, Sultans would be chosen by a committee of several important members of the various Isaaq subclans. Sultans were usually buried at Toon, south of Hargeisa, which was a significant site and the capital of the Sultanate during Farah Guled's rule.[73]

| Name | Reign from | Reign till | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdi Eisa (Traditional Chief) | Mid 1700s | Mid 1700s | |

| Sultan Guled Abdi (First Sultan) | 1750 | 1808 | |

| Sultan Farah Sultan Guled | 1808 | 1845 | |

| Sultan Hassan Sultan Farah | 1845 | 1870 | |

| Sultan Deria Sultan Hassan | 1870 | 1939 (Creation of British Somaliland in 1884) |

|

| Sultan Abdillahi Sultan Deria | 1939 | 1967 |

|

| Sultan Rashid Sultan Abdillahi | 1967 | 1969 |

|

| Sultan Abdiqadir Sultan Abdillahi | 1969 | 1975 | |

| Sultan Mohamed Sultan Abdiqadir | 1975 | 2021 |

|

| Sultan Daud Sultan Mohamed | 2021 |

|

Battle of Berbera

The first engagement between Somalis of the region and the British was in 1825 and led to hostilities,[74] ending in the Battle of Berbera and a subsequent trade agreement between the Habr Awal and the United Kingdom.[75][76] This was followed by a British treaty with the Governor of Zeila in 1840. An engagement was then started between the British and elders of Habar Garhajis and Habar Toljaala clans of the Isaaq in 1855, followed a year later by the conclusion of the "Articles of Peace and Friendship" between the Habar Awal and East India Company. These engagements between the British and Somali clans culminated in the formal treaties the British signed with the henceforth 'British Somaliland' clans, which took place between 1884 and 1886 (treaties were signed with the Habar Awal, Gadabursi, Habar Toljaala, Habar Garhajis, Esa, and the Warsangali clans), and paved the way for the British to establish a protectorate in the region referred to as British Somaliland.[77] The British garrisoned the protectorate from Aden and administered it as part of British India until 1898. British Somaliland was then administered by the Foreign Office until 1905, and afterwards by the Colonial Office.[78]

British Somaliland

The Somaliland Campaign, also called the Anglo-Somali War or the Dervish War, was a series of military expeditions that took place between 1900 and 1920 in the Horn of Africa, pitting the Dervishes led by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (nicknamed the "Mad Mullah") against the British.[79] The British were assisted in their offensives by the Ethiopians and Italians. During the First World War (1914–1918), Hassan also received aid from the Ottomans, Germans and, for a time, from the Emperor Iyasu V of Ethiopia. The conflict ended when the British aerially bombed the Dervish capital of Taleh in February 1920.[80]

The Fifth Expedition of the Somaliland campaign in 1920 was the final British expedition against the Dervish forces of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, the Somali religious leader. Although most of the combat took place in January of the year, British troops had begun preparations for the assault as early as November 1919. The British forces included elements of the Royal Air Force and the Somaliland Camel Corps. After three weeks of battle, Hassan's Dervishes were defeated, bringing an effective end to their 20-year resistance.[81] It was one of the bloodiest and longest militant movements in sub-Saharan Africa during the colonial era, one that overlapped with World War I. The battles between various sides over two decades killed nearly a third of Somaliland's population and ravaged the local economy.[82][83][84]

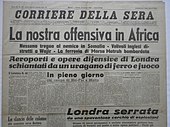

The Italian conquest of British Somaliland was a military campaign in East Africa, which took place in August 1940 between forces of Italy and those of several British and Commonwealth countries. The Italian attack was part of the East African campaign.[85]

Anti-colonial resistance

Burao Tax Revolt and RAF bombing

The people of Burao clashed with the British in 1922. They revolted in opposition to a new tax that was imposed upon them, rioting and attacking British government officials. This led to a shootout between the British and Burao residents in which Captain Allan Gibb, a Dervish war veteran and district commissioner, was shot and killed. The British requested Sir Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, to send troops from Aden and Air Force bombers Burao the revolting clans' livestock.[86] The RAF planes arrived at Burao within two days and proceeded to bomb the town with incendiaries, effectively burning the entire settlement to the ground.[87][88][89][90]

Telegram from Sir Geoffrey Archer, Governor of British Somaliland to Sir Winston Churchill the Secretary of State for the Colonies:

I deeply regret to inform that during an affray at Burao yesterday between Rer Sugulleh and Akils of other tribes Captain Gibb was shot dead. Having called out Camel corps company to quell the disturbance, he went forward himself with his interpreter, whereupon fire opened on him by some Rer segulleh riflemen and he was instantly killed..Miscreants then disappeared under the cover of darkness. In order to meet the situation created by the Murder of Gibb, we require two aeroplanes for about fourteen days. I have arranged with resident, Aden, for these. And made formal application, which please confirm. It is proposed they fly via Perim, confining sea crossing to 12 miles. We propose to inflict fine of 2,500 camels on implicated sections, who are practically isolated and demand surrender of man who killed Gibbs. He is known. Fine to be doubled in failure to comply with latter conditions and aeroplanes to be used to bomb stock on grazing grounds.[91]

Sir Winston Churchill reporting on the Burao incident at the House of Commons:

On 25th February the Governor of Somaliland telegraphed that an affray between tribesmen had taken place at Burao on the previous day, in the course of which Captain Allan Gibb, D.S.O., D.C.M., the District Commissioner at Burao, had been shot dead. Captain Gibb had advanced with his interpreter to quell the disturbance, when 1954 fire was opened upon him by some riflemen, and he was instantly killed. The murderers escaped under cover of falling darkness. Captain Gibb was an officer of long and valued service in Somaliland, whose loss I deeply regret. From the information available, his murder does not appear to have been premeditated, but it inevitably had a disturbing effect upon the surrounding tribes, and immediate dispositions of troops became necessary in order to ensure the apprehension and punishment of those responsible for the murder. On 27th February the Governor telegraphed that, in order to meet the situation which had arisen, he required two aeroplanes for purposes of demonstration, and suggested that two aeroplanes from the Royal Air Force Detachment at Aden should fly over to Berber a from Aden. He also telegraphed that in certain circumstances it might become necessary to ask for reinforcements of troops to be sent to the Protectorate.[92]

James Lawrence author of Imperial Rearguard: Wars of Empire writes

..was murdered by rioters during a protest against taxation at Burao. Governor Archer immediately called for aircraft which were at Burao within two days. The inhabitants of the native township were turned out of their houses, and the entire area was razed by a combination of bombing, machine-gun fire and burning.[93]

After the RAF aircraft bombed Burao to the ground, the leaders of the rebellion acquiesced, agreeing to pay a fine for Gibb's death, but they refused to identify and apprehend the accused individuals. Most of the men responsible for Gibb's shooting evaded capture. In light of the failure to implement the taxation without provoking a violent response, the British abandoned the policy altogether.[94][95][90]

1945 Sheikh Bashir Rebellion

The 1945 Sheikh Bashir Rebellion was a rebellion waged by tribesmen of the Habr Je'lo clan in the former British Somaliland protectorate against British authorities in July 1945 led by Sheikh Bashir, a Somali religious leader.[96]

On 2 July, Sheikh Bashir collected 25 of his followers in the town of Wadamago and transported them on a lorry to the vicinity of Burao, where he distributed arms to half of his followers. On the evening of 3 July, the group entered Burao and opened fire on the police guard of the central prison in the city, which was filled with prisoners arrested for previous demonstrations. The group also attacked the house of the district commissioner of Burao District, Major Chambers, resulting in the death of Major Chamber's police guard before escaping to Bur Dhab, a strategic mountain south-east of Burao, where Sheikh Bashir's small unit occupied a fort and took up a defensive position in anticipation of a British counterattack.[97]

The British campaign against Sheikh Bashir's troops proved abortive after several defeats as his forces kept moving from place to place and avoiding any permanent location. No sooner had the expedition left the area, than the news travelled fast among the Somali nomads across the plain. The war had exposed the British administration to humiliation. The government came to a conclusion that another expedition against him would be useless; that they must build a railway, make roads and effectively occupy the whole of the protectorate, or else abandon the interior completely. The latter course was decided upon, and during the first months of 1945, the advance posts were withdrawn, and the British administration confined to the coast town of Berbera.[98]

Sheikh Bashir settled many disputes among the tribes in the vicinity, which kept them from raiding each other. He was generally thought to settle disputes through the use of Islamic Sharia and gathered around him a strong following.[99]

The British administration recruited Indian and South African troops, led by police general James David, to fight against Sheikh Bashir and had intelligence plans to capture him alive. The British authorities mobilised a police force, and eventually on 7 July found Sheikh Bashir and his unit in defensive positions behind their fortifications in the mountains of Bur Dhab. After clashes Sheikh Bashir and his second-in-command, Alin Yusuf Ali, nicknamed Qaybdiid, were killed. A third rebel was wounded and was captured along with two other rebels. The rest fled the fortifications and dispersed. On the British side the police general leading the British troops as well as a number of Indian and South African troops perished in the clashes, and a policeman was injured.[99]

After his death, Sheikh Bashir was widely hailed by locals as a martyr and was held in great reverence. His family took quick action to remove his body from the place of his death at Geela-eeg mountain, about 20 miles from Burao.[100]

State of Somaliland (Independence)

Initially the British government planned to delay protectorate of British Somaliland independence in favour of a gradual transfer of power. The arrangement would allow local politicians to gain more political experience in running the protectorate before official independence. However, strong pan-Somali nationalism and a landslide victory in the earlier elections encouraged them to demand independence and unification with the Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian Administration (the former Italian Somaliland).[101]

In May 1960, the British government stated that it would be prepared to grant independence to the then protectorate of British Somaliland, with the intention that the territory would unite with the Italian-administered Trust Territory of Somaliland.[102] The Legislative Council of British Somaliland passed a resolution in April 1960 requesting independence and union with the Trust Territory of Somaliland, which was scheduled to gain independence on 1 July that year. The legislative councils of both territories agreed to this proposal following a joint conference in Mogadishu.[103] On 26 June 1960, the former British Somaliland protectorate briefly obtained independence as the State of Somaliland, with the Trust Territory of Somaliland following suit five days later.[16] During its brief period of independence, the State of Somaliland garnered recognition from thirty-five sovereign states.[104] However, the United States merely acknowledged Somaliland's independence:

The United States did not extend formal recognition to Somaliland, but Secretary of State Herter sent a congratulatory message dated June 26 to the Somaliland Council of Ministers.[105]

The following day, on 27 June 1960, the newly convened Somaliland Legislative Assembly approved a bill that would formally allow for the union of the State of Somaliland with the Trust Territory of Somaliland on 1 July 1960.[103]

Somali Republic (union with Somalia)

On 1 July 1960, the State of Somaliland and the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland) united as planned to form the Somali Republic.[106][107] Inspired by Somali nationalism, the northerners were initially enthusiastic about the union.[108] A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa, with Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister (later becoming president, from 1967 to 1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum, the Somali people ratified a new constitution, which was first drafted in 1960.[109] The constitution had little support in the former Somaliland and was believed to favour the south. Many northerners boycotted the referendum in protest, and over 60% of those who voted in the north were against the new constitution. Regardless, the referendum passed, and Somaliland became quickly dominated by southerners. As result, dissatisfaction became widespread in the north, and support for the union plummeted. British-trained Somaliland officers attempted a revolt to end the union in December 1961. Their uprising failed, and Somaliland continued to be marginalised by the south during the next decades.[108]

In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke. Shermarke was assassinated two years later by one of his own bodyguards. His murder was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somalian Army seized power without encountering armed opposition. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[110] The new regime would go on to rule Somalia for the next 22 years.[111]

Somali National Movement, Barre persecution

The moral authority of Barre's government was gradually eroded, as many Somalis became disillusioned with life under military rule. By the mid-1980s, resistance movements supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration had sprung up across the country, which led to the Somaliland War of Independence. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerrillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included bombing of cities, with the northwestern administrative centre of Hargeisa, a Somali National Movement (SNM) stronghold, among the targeted areas in 1988.[112][113] The bombardment was led by General Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan, Barre's son-in-law.[114]

In May 1988, the SNM launched a major offensive on the cities of Hargeisa and Burao,[115][116][117] then the second and third largest cities of Somalia.[118][119] The SNM captured Burao on 27 May within two hours,[120] while the SNM entered Hargeisa on 29 May, overrunning most of the city apart from its airport by 1 June.[116]

According to Abou Jeng and other scholars, the Barre regime rule was marked by a targeted brutal persecution of the Isaaq clan.[121][122] Mohamed Haji Ingiriis and Chris Mullin state that the clampdown by the Barre regime against the Hargeisa-based Somali National Movement targeted the Isaaq clan, to which most members of the SNM belonged. They refer to the clampdown as the Isaaq Genocide or “Hargeisa Holocaust”.[123][124] A United Nations investigation concluded that the crime of genocide was "conceived, planned and perpetrated by the Somali Government against the Isaaq people".[125] The number of civilian casualties is estimated to be between 50,000 and 100,000 according to various sources,[126][127][128] while some reports estimate the total civilian deaths to be upwards of 200,000 Isaaq civilians.[129] Along with the deaths, Barre regime bombarded and razed the second and third largest cities in Somalia, Hargeisa and Burao, respectively.[130] This displaced an estimated 400,000 local residents to Hart Sheik in Ethiopia;[131][132][133] another 400,000 individuals were also internally displaced.[134][135][136]

The counterinsurgency by the Barre regime against the SNM targeted the rebel group's civilian base of support, escalating into a genocidal onslaught against the Isaaq clan. This led to anarchy and violent campaigns by fragmented militias, which then wrested power at a local level.[137] The Barre regime's persecution was not limited to the Isaaq, as it targeted other clans such as the Hawiye.[138][139] The Barre regime collapsed in January 1991. Thereafter, as the political situation in Somaliland stabilised, the displaced people returned to their homes, the militias were demobilised or incorporated into the army, and tens of thousands of houses and businesses were reconstructed from rubble.[140]

Restoration of sovereignty (end of the unity with Somalia)

Although the SNM at its inception had a unionist constitution, it eventually began to pursue independence, looking to secede from the rest of Somalia.[141] Under the leadership of Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur, the local administration declared the northwestern Somali territories independent at a conference held in Burao between 27 April 1991 and 15 May 1991.[142] Tuur then became the newly established Somaliland polity's first President, but subsequently renounced the separatist platform in 1994 and began instead to publicly seek and advocate reconciliation with the rest of Somalia under a power-sharing federal system of governance.[141] A brief armed conflict had begun in January 1992 against rebels against Tuur in the period that he was in power, lasting until August 1992, when it was settled by a conference at the town of Sheikh.[143]

Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal was appointed as Tuur's successor in 1993 by the Grand Conference of National Reconciliation in Borama, which met for four months, leading to a gradual improvement in security, as well as a consolidation of the new territory.[144] Another armed conflict between the Somaliland government, now under Egal, and rebels began, as militias of the Eidagalley clan occupied Hargeisa airport for some time. Conflict re-erupted when troops of the government attacked the airport to drive out the Eidagalley militias in October 1994, sparking a new war that would spread out of Hargeisa and last until around April 1995, with a rebel defeat. Around the same time, Djiboutian-backed forces of the Issa-dominated United Somali Front attempted and failed to carve out Issa-inhabited areas of Somaliland.[143] Egal was reappointed in 1997, and remained in power until his death on 3 May 2002. The vice-president, Dahir Riyale Kahin, who was during the 1980s the highest-ranking National Security Service (NSS) officer in Berbera in Siad Barre's government, was sworn in as president shortly afterward.[145] In 2003, Kahin became the first elected president of Somaliland.[146]

The war in southern Somalia between Islamist insurgents on the one hand, and the Federal Government of Somalia and its African Union allies on the other, has for the most part not directly affected Somaliland, which, like neighbouring Puntland, has remained relatively stable.[147][148]

2001 constitutional referendum

In August 2000, President Egal's government distributed thousands of copies of the proposed constitution throughout Somaliland for consideration and review by the people. One critical clause of the 130 individual articles of the constitution would ratify Somaliland's self-declared independence and final separation from Somalia, restoring the nation's independence for the first time since 1960. In late March 2001, President Egal set the date for the referendum on the Constitution for 31 May 2001.[149][150] 99.9% of eligible voters took part in the referendum and 97.1% of them voted in favour of the constitution.[151]

2023 Las Anod conflict

On 6 February 2023, the Dhulbahante clan elders of Las Anod declared their intent to secede from Somaliland and form a state government named "SSC-Khatumo" within the Federal Government of Somalia, triggering armed conflict.

Politics and government

Constitution

The Constitution of Somaliland defines the political system; the Republic of Somaliland is a unitary state and presidential republic, based on peace, co-operation, democracy and a multi-party system.[152]

President and cabinet

The executive is led by an elected president, whose government includes a vice-president and a Council of Ministers.[153] The Council of Ministers, who are responsible for the normal running of government, are nominated by the President and approved by the Parliament's House of Representatives.[154] The President must approve bills passed by the Parliament before they come into effect.[153] Presidential elections are confirmed by the National Electoral Commission of Somaliland.[155] The President can serve a maximum of two five-year terms.

Parliament

Legislative power is held by the Parliament, which is bicameral. Its upper house is the House of Elders, chaired by Suleiman Mohamoud Adan, and the lower house is the House of Representatives,[153] chaired by Yasin Haji Mohamoud.[156] Each house has 82 members. Members of the House of Elders are elected indirectly by local communities for six-year terms. The House of Elders shares power in passing laws with the House of Representatives, and also has the role of solving internal conflicts, and exclusive power to extend the terms of the President and representatives under circumstances that make an election impossible. Members of the House of Representatives are directly elected by the people for five-year terms. The House of Representatives shares voting power with the House of Elders, though it can pass a law that the House of Elders rejects if it votes for the law by a two-thirds majority and has absolute power in financial matters and confirmation of Presidential appointments (except for the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court).[157]

Law

The judicial system is divided into district courts (which deal with matters of family law and succession, lawsuits for amounts up to 3 million SLSH, criminal cases punishable by up to 3 years' imprisonment or 3 million SL fines, and crimes committed by juveniles), regional courts (which deal with lawsuits and criminal cases not within the jurisdiction of district courts, labour and employment claims, and local government elections), regional appeals courts (which deal with all appeals from the district and regional courts), and the Supreme Court (which deals with issues between courts and in government, and reviews its own decisions), which is the highest court and also functions as the Constitutional Court.[158]

Somaliland nationality law defines who is a Somaliland citizen,[159] as well as the procedures by which one may be naturalised into Somaliland citizenship or renounce it.[160]

The Somaliland government continues to apply the 1962 penal code of the Somali Republic. As such, homosexual acts are illegal in the territory.[161]

Parties and elections

The guurti worked with rebel leaders to set up a new government, and was incorporated into the governance structure, becoming the Parliament's House of Elders.[162] The government became in essence a "power-sharing coalition of Somaliland's main clans", with seats in the Upper and Lower houses proportionally allocated to clans according to a predetermined formula, although not all clans are satisfied with their representation.[citation needed] In 2002, after several extensions of this interim government, Somaliland transitioned to multi-party democracy.[163] The election was limited to three parties, in an attempt to create ideology-based elections rather than clan-based elections.[162] As of December 2014, Somaliland has three political parties: the Peace, Unity, and Development Party, the Justice and Development Party, and Wadani. Under the Somaliland Constitution, a maximum of three political parties at the national level is allowed.[164] The minimum age required to vote is 15.

Freedom House ranks the Somaliland government as partly free.[165] Seth Kaplan (2011) argues that in contrast to southern Somalia and adjacent territories, Somaliland, the secessionist northwestern portion of Somalia, has built a more democratic mode of governance from the bottom up, with virtually no foreign assistance.[166] Specifically, Kaplan suggests that Somaliland has the most democratic political system in the Horn of Africa because it has been largely insulated from the extremist elements in the rest of Somalia and has viable electoral and legislative systems as well as a robust private sector-dominated economy, unlike neighbouring authoritarian governments. He largely attributes this to Somaliland's integration of customary laws and tradition with modern state structures, which he indicates most post-colonial states in Africa and the Middle East have not had the opportunity to do. Kaplan asserts that this has facilitated cohesiveness and conferred greater governmental legitimacy in Somaliland, as has the territory's comparatively homogeneous population, relatively equitable income distribution, a common fear of the south, and absence of interference by outside forces, which has obliged local politicians to observe a degree of accountability.[167]

Foreign relations

Somaliland has political contacts with its neighbours Ethiopia[168] and Djibouti,[169] non-UN member state Republic of China (Taiwan),[170][171] as well as with South Africa,[168] Sweden,[172] the United Kingdom,[173] and the micronation of Liberland.[174][175][176][177][178] On 17 January 2007, the European Union (EU) sent a delegation for foreign affairs to discuss future co-operation.[179] The African Union (AU) has also sent a foreign minister to discuss the future of international acknowledgment, and on 29 and 30 January 2007, the ministers stated that they would discuss acknowledgement with the organisation's member states.[180] In early 2006, the National Assembly for Wales extended an official invitation to the Somaliland government to attend the royal opening of the Senedd building in Cardiff. The move was seen as an act of recognition by the Welsh Assembly of the breakaway government's legitimacy. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office made no comment on the invitation. Wales is home to a significant Somali expatriate community from Somaliland.[181]

In 2007, a delegation led by President Kahin was present at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Kampala, Uganda. Although Somaliland has applied to join the Commonwealth under observer status, its application is still pending.[182]

On 24 September 2010, Johnnie Carson, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, stated that the United States would be modifying its strategy in Somalia and would seek deeper engagement with the governments of Somaliland and Puntland while continuing to support the Somali Transitional Government.[183] Carson said the US would send aid workers and diplomats to Puntland and Somaliland and alluded to the possibility of future development projects. However, Carson emphasised that the US would not extend formal recognition to either region.[184]

The then-UK Minister for Africa, Henry Bellingham MP, met President Silanyo of Somaliland in November 2010 to discuss ways in which to increase the UK's engagement with Somaliland.[185] President Silanyo said during his visit to London: "We have been working with the international community and the international community has been engaging with us, giving us assistance and working with us in our democratisation and development programmes. And we are very happy with the way the international community has been dealing with us, particularly the UK, the US, other European nations, and our neighbours who continue to seek recognition."[186]

Recognition of Somaliland by the UK was also supported by the UK Independence Party, which came third in the popular vote at the 2015 general election, though only electing a single MP. The leader of UKIP, Nigel Farage, met with Ali Aden Awale, Head of the Somaliland UK Mission on Somaliland's national day, 18 May, in 2015, to express UKIP's support for Somaliland.[187]

In 2011, Somaliland and the neighbouring Puntland region each entered a security-related memorandum of understanding with the Seychelles. Following the framework of an earlier agreement signed between the Transitional Federal Government and Seychelles, the memorandum is "for the transfer of convicted persons to prisons in 'Puntland' and 'Somaliland'."[188]

Zdroj:https://en.wikipedia.org?pojem=Transport_in_Somaliland

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.