A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | CH | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

Fritware, also known as stone-paste, is a type of pottery in which frit (ground glass) is added to clay to reduce its fusion temperature. The mixture may include quartz or other siliceous material. An organic compound such as gum or glue may be added for binding. The resulting mixture can be fired at a lower temperature than clay alone. A glaze is then applied on the surface.

Fritware was invented to give a strong white body, which, combined with tin-glazing of the surface, allowed it to approximate the result of Chinese porcelain. Porcelain was not manufactured in the Islamic world until modern times, and most fine Islamic pottery was made of fritware. Frit was also a significant component in some early European porcelains.

A small manufacturing cluster of fritware exists around Jaipur, Rajasthan in India, where it is known as 'Blue Pottery' due its most popular glaze. The Blue Pottery of Jaipur technique may have arrived in India with the Mughals,[1] with production in Jaipur dating to at least as early as the 17th century.[2][3]

Composition and techniques

Fritware was invented in the Medieval Islamic world to give a strong white body, which, combined with tin-glazing of the surface, allowed it to approximate the white colour, translucency, and thin walls of Chinese porcelain. True porcelain was not manufactured in the Islamic world until modern times, and most fine Islamic pottery was made of fritware. Frit was also a significant component in some early European porcelains.

Although its production centres may have shifted with time and imperial power, fritware remained in continued use throughout the Islamic world with little significant innovation.[4] The technique was used to create many other significant artistic traditions such as lustreware, Raqqa ware, and Iznik pottery.[5][6]

Raw materials in one contemporary recipe used in Jaipur are quartz powder, glass power, fuller's earth, borax and tragacanth gum.[7][8] Raw materials for a glaze are reported to be glass powder, lead oxide, borax, potassium nitrate, zinc oxide and boric acid. The blue decoration is cobalt oxide.[9]

History

Frit is crushed glass that is used in ceramics. The pottery produced from the manufacture of frit is often called 'fritware' but has also been referred to as "stonepaste" and "faience" among other names.[10] Fritware was innovative because the glaze and the body of the ceramic piece were made of nearly the same materials, allowing them to fuse better, be less likely to flake, and could also be fired at a lower temperature.[11] Such traditions of low firing temperatures were not uncommon throughout the Middle East and Central Asia, having examples of the technique dating to the 11th century BC when it may have been developed.[12]

The manufacture of proto-fritware began in Iraq in the 9th century AD under the Abbasid Caliphate,[13] and with the establishment of Samarra as its capital in 836, there is extensive evidence of ceramics in the court of the Abbasids both in Samarra and Baghdad.[14] A ninth-century corpus of 'proto-stonepaste' from Baghdad has "relict glass fragments" in its fabric.[10] The glass is alkali-lime-lead-silica and, when the paste was fired or cooled, wollastonite and diopside crystals formed within the glass fragments. The lack of "inclusions of crushed pottery" suggests these fragments did not come from a glaze.[10] The reason for their addition would have been to release alkali into the matrix on firing, which would "accelerate vitrification at a relatively low firing temperature, and thus increase the hardness and density of the body."[10]

Following the fall of the Abbasid Caliphate, the main centres of manufacture moved to Egypt where true fritware was invented between the 10th and the 12th centuries under the Fatimids, but the technique then spread throughout the Middle East.[13]

There are many variations on designs, colour, and composition, the last often attributed to the differences in mineral compositions of soil and rock used in the production of fritware.[5] The bodies of the fritware ceramics were always made quite thin to imitate their porcelain counterparts in China, a practice not common before the discovery of the frit technique which produced stronger ceramics.[11] In the 13th century the town of Kashan in Iran was an important centre for the production of fritware.[15] Abū'l-Qāsim, who came from a family of tilemakers in the city, wrote a treatise in 1301 on precious stones that included a chapter on the manufacture of fritware.[16] His recipe specified a fritware body containing a mixture of 10 parts silica to 1 part glass frit and 1 part clay. The frit was prepared by mixing powdered quartz with soda which acted as a flux. The mixture was then heated in a kiln.[16][10] The internal circulation of pottery within the Islamic world from its earliest days was quite common, with the movement of ideas regarding pottery without their physical presence in certain areas being readily apparent.[14] The movement of fritware into China - whose monopoly on porcelain production had prompted the Islamic world to produce fritware to begin with - impacted Chinese porcelain decoration, deriving the signature cobalt blue colour from Islamic traditions of fritware decoration.[17] The transfer of this artistic idea was likely a consequence of the enhanced connection and trade relations between the Middle and Near East and Far East Asia under the Mongols beginning in the 13th century.[17] The Middle and Near East had an initial monopoly on the cobalt colour due to its own richness in cobalt ore, which was especially abundant in Qamsar and Anarak in Persia.[18]

Iznik pottery was produced in Ottoman Turkey beginning in the last quarter of 15th century AD.[6] It consists of a body, slip, and glaze, where the body and glaze are 'quartz-frit'.[6] The 'frits' in both cases "are unusual in that they contain lead oxide as well as soda"; the lead oxide would help reduce the thermal expansion coefficient of the ceramic.[6] Microscopic analysis reveals that the material that has been labeled 'frit' is 'interstitial glass' which serves to connect the quartz particles.[6] The glass was added as frit and the interstitial glass formed on firing.

In 2011, 29 potteries, employing a total of 300 persons, making fritware were identified in Jaipur.[19]

Applications

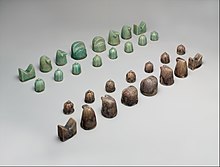

Fritware served a wide variety of purposes in the medieval Islamic world. As a porcelain substitute, the fritware technique was used to craft bowls, vases, and pots, not only as symbols of luxury but also to practical ends.[5] It was similarly used by medieval tilemakers to craft strong tiles with a colourless body that provided a suitable base for underglaze and decoration.[14] Fritware was also known to be used to craft objects beyond pottery and tiling, and has been found to be used in the twelfth century to make objects like chess sets.[20] There is also a tradition of using fritware to create intricate figurines, with surviving examples from the Seljuk Empire.[21]

It was also used as the ceramic body for Islamic lustreware, a technique that puts a lustred ceramic glaze onto pottery.[5]

References

- ^ "Colour me bright & blue". 20 February 2016.

- ^ 'Managing Dwindling Glaze Of Jaipur Blue Pottery: A Case Of Rajasthan, India' Mathur A.K, Shukla D. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences. Vol. 3, No. 12, December 2014

- ^ 'Tryst with Tradition - Exploring Rajasthan Through the Alankar Museum' Jawahar Kala Kendra. Alankar Museum. 2011. Pg. 6

- ^ Mason, Robert (1995). "New looks at old pots: Results of recent multidisciplinary studies of glazed ceramics from the Islamic world". Muqarnas. 12: 1–10. doi:10.2307/1523219. JSTOR 1523219.

- ^ a b c d Redford, Scott; Blackman, M. James (1997). "Luster and fritware production and distribution in medieval Syria". Journal of Field Archaeology. 24 (2): 233–247. doi:10.1179/009346997792208230.

- ^ a b c d e Tite, M.S. (1989). "Iznik pottery: an investigation of the methods of production". Archaeometry. 31 (2): 115–132. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1989.tb01008.x.

- ^ 'An Interactive Design Study of Jaipur Blue Pottery' Need Assessment Survey Report, MSME Design Clinic Scheme. 2011. Pgs. 9–11

- ^ 'Evolution of Blue Pottery Industry in Rajasthan' Bhardwaj A. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews. Vol. 5, Iss. 3 July–Sept. 2018

- ^ 'Blue Pottery of Jaipur' Pande A. International Journal of Research - Granthaalayah. Vol.7. Iss.3. March 2019

- ^ a b c d e Mason, R.B.; Tite, M.S. (1994). "The beginnings of Islamic stonepaste technology". Archaeometry. 36: 77–91. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1994.tb01066.x.

- ^ a b Lane, Arthur (1947). Early Islamic Pottery: Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia. London: Faber and Faber. p. 32.

- ^ Raghavan, Raju. "Ceramics in China". Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures: 1103–1117.

- ^ a b Archaeological chemistry by Zvi Goffer p.254

- ^ a b c Watson, Oliver (2017). "Ceramics and circulation". In Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoglu, Gulru (eds.). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 478–500. ISBN 978-1-119-06857-0.

- ^ Atasoy, Nurhan; Raby, Julian (1989). Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey. London: Alexandra Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-85669-054-6.

- ^ a b Allan, J.W. (1973). "Abū'l-Qāsim's treatise on ceramics". Iran. 11: 111–120. doi:10.2307/4300488. JSTOR 4300488.

- ^ a b Medley, Margaret (1975). "Islam, Chinese porcelain and Ardabīl". Iran. 13: 31–37. doi:10.2307/4300524. JSTOR 4300524.

- ^ Zucchiatti, A.; Bouquillon, A.; Katona, I.; D'Alessandro, A. (2006). "The 'Della Robbia Blue': A case study for the use of cobalt pigments in ceramics during the Italian Renaissance". Archaeometry. 48: 131–152. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2006.00247.x.

- ^ 'An Interactive Design Study of Jaipur Blue Pottery' Need Assessment Survey Report, MSME Design Clinic Scheme. 2011. Pgs. 9-11

- ^ Kenney, Ellen (2011). "Chess Set". MET Museum. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Canby, S.R.; Beyazit, D.; Rugiadi, M.; Peacock, A.C.S. (2016). Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-589-4.

Further reading

- Mason, Robert B.; Gonnella, Julia (2000). "The petrology of Syrian stonepaste ceramics: the view from Aleppo". Internet Archaeology. 9 (9). doi:10.11141/ia.9.10.

- Tite, M.S.; Wolf, S.; Mason, R.B. (2011). "The technological development of stonepaste ceramics from the Islamic Middle East". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (3): 570–580. Bibcode:2011JArSc..38..570T. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.10.011. S2CID 16576495.

- "Technology of Frit Making in Iznik." Okyar F. Euro Ceramics VIII, Part 3. Trans Tech Publications. 2004, p. 2391-2394. Published for The European Ceramic Society.

- Pancaroğlu, O. (2007). Perpetual glory: Medieval Islamic ceramics from the Harvey B. Plotnick Collection (1055933707 805629715 M. Bayani, Trans.). Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago.

- Watson, O. (2004). Ceramics from Islamic lands. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson.

>Text je dostupný pod licencí Creative Commons Uveďte autora – Zachovejte licenci, případně za dalších podmínek. Podrobnosti naleznete na stránce Podmínky užití.

Porcelain

Iran

British Museum

File:Blue and White Bowl with Radial Design, 13th century.jpg

Brooklyn Museum

File:Cypress Tree Decorated Ottoman Pottery P1000591.JPG

İznik pottery

Calouste Gulbenkian Museum

Pottery

Frit

Clay

Quartz

Natural gum

Glue

Ceramic glaze

Tin-glazing

Chinese porcelain

Porcelain

Islamic pottery

Jaipur

Rajasthan

Blue Pottery of Jaipur

Tin-glazing

Chinese porcelain

Porcelain

Islamic pottery

Frit

Lustreware

Raqqa ware

Iznik pottery

Fuller's earth

Borax

Tragacanth

Lead oxide

Potassium nitrate

Zinc oxide

Boric acid

Cobalt oxide

Frit

Egyptian faience

File:Chess Set MET DP170393.jpg

Nishapur

Iran

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Abbasid Caliphate

Samarra

Baghdad

Wollastonite

Diopside

Egypt

Fatimid Caliphate

Middle-East

File:Stone paste dish Iznik Turkey 1550 1570.JPG

Iznik pottery

Turkey

British Museum

Kashan

Silicon dioxide

Sodium carbonate

Ceramic flux

Chinese influences on Islamic pottery

Chinese ceramics

Cobalt blue

Iznik pottery

Ottoman Empire

Coefficient of thermal expansion

File:Blue pottery from Jaipur 2.jpg

Seljuk Empire

Lustreware

Ceramic glaze

Doi (identifier)

JSTOR (identifier)

Doi (identifier)

Doi (identifier)

Doi (identifier)

ISBN (identifier)

Special:BookSources/978-1-119-06857-0

Nurhan Atasoy

ISBN (identifier)

Special:BookSources/978-1-85669-054-6

Doi (identifier)

JSTOR (identifier)

Doi (identifier)

JSTOR (identifier)

Doi (identifier)

ISBN (identifier)

Special:BookSources/978-1-58839-589-4

Category:Stone-paste

Doi (identifier)

Bibcode (identifier)

Doi (identifier)

S2CID (identifier)

Template:Islamic art

Template talk:Islamic art

Special:EditPage/Template:Islamic art

Islamic art

Islamic architecture

Abbasid architecture

Ayyubid dynasty#Architecture

Architecture of Azerbaijan

Islamic architecture#Chinese

Fatimid architecture

Hausa architecture

Indo-Islamic architecture

Bengali Muslim architecture

Architecture of the Deccan sultanates

Qutb Shahi architecture

Mughal architecture

Mosque architecture in Indonesia

Islamic architecture#Malaysia

Iranian architecture

Khorasani style

Isfahani style

Traditional Persian residential architecture

Mamluk architecture

Moorish architecture

Mudéjar art

Ottoman architecture

Seljuk architecture

Somali architecture

Sudano-Sahelian architecture

Swahili architecture

Tatar mosque

Timurid Empire#Timurid architecture

Umayyad architecture

Islamic architecture#Yemeni

Category:Islamic architectural elements

Ablaq

Banna'i

Iwan

Jali

Mashrabiya

Mihrab

Minaret

Mocárabe

Muqarnas

Sitara (textile)

Stucco decoration in Islamic architecture

File:Islamic Tiling (186943375).jpeg

Bangladeshi art

Persian art

Persian art#Early Islamic period

Qajar art

Safavid art

Turkish art

Culture of the Ottoman Empire#Decorative arts

Oriental rug

Gul (design)

Kilim

Kilim motifs

Persian carpet

Turkish carpet

Prayer rug

Islamic pottery

Hispano-Moresque ware

İznik pottery

Islamic lustreware

Mina'i ware

Persian pottery

Chinese influences on Islamic pottery

Batik

Damask

Ikat

Islamic embroidery

Soumak

Suzani (textile)

Khatam

Minbar

Islamic music

Islamic art#Islamic brasswork

Damascus steel

Enamelled glass#Islamic

Islamic glass

Hardstone carving#Islamic hardstone carving

Ivory carving#Islamic ivory

Mosque lamp

Shabaka (window)

Islamic miniature

Arabic miniature

Mughal painting

Ottoman miniature

Persian miniature

Islamic calligraphy

Arabic calligraphy

Diwani

Indian calligraphy

Kufic

Muhaqqaq

Naskh (script)

Nastaʿlīq

Persian calligraphy

Sini (script)

Taʿlīq

Thuluth

Tughra

Muraqqa

Hilya

Ottoman illumination

Islamic ornament

Arabesque

Islamic geometric patterns

Girih

Girih tiles

Zellij

Islamic garden

Charbagh

Mughal garden

Ottoman gardens

Paradise garden

Persian gardens

List of museums of Islamic art

Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin

Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo

Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

Museum of Islamic Art, Ghazni

Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum

Museum of Turkish Calligraphy Art

Islamic Museum, Jerusalem

L. A. Mayer Institute for Islamic Art

Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia

British Museum#Islamic art

Victoria and Albert Museum#Islamic art

Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

Los Angeles County Museum of Art#Islamic art

Marrakech Museum

Majorelle Garden

Islamic Museum of Australia

Arab World Institute

Louvre#Islamic art

Asian Civilisations Museum

Aga Khan Museum

Islamic Museum of Tripoli

Empire of the Sultans

Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam

Islamic Art: Mirror of the Invisible World

Aniconism in Islam

Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture

Islamic world contributions to Medieval Europe

Islamic influences on Western art

Grotesque

Moresque

Mathematics and architecture

Moorish Revival architecture

Mudéjar

Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting

Pseudo-Kufic

Stilfragen

Topkapı Scroll

Fritware

Fritware

Main Page

Wikipedia:Contents

Portal:Current events

Special:Random

Wikipedia:About

Wikipedia:Contact us

Special:FundraiserRedirector?utm source=donate&utm medium=sidebar&utm campaign=C13 en.wikipedia.org&uselang=en

Help:Contents

Help:Introduction

Wikipedia:Community portal

Special:RecentChanges

Wikipedia:File upload wizard

Main Page

Special:Search

Help:Introduction

Special:MyContributions

Special:MyTalk

عجينة الحجر

Frittenporzellan

Frittkeraamika

Fritware

Ceramica vitrea

ソフトペースト

Fritware

Фриттовый фарфор

Đồ gốm frit

Special:EntityPage/Q1458831#sitelinks-wikipedia

Fritware

Talk:Fritware

Fritware

Fritware

Special:WhatLinksHere/Fritware

Special:RecentChangesLinked/Fritware

Wikipedia:File Upload Wizard

Special:SpecialPages

Special:EntityPage/Q1458831

Category:Stone-paste

Fritware

Fritware

Main Page

Wikipedia:Contents

Portal:Current events

Special:Random

Wikipedia:About

Wikipedia:Contact us

Special:FundraiserRedirector?utm source=donate&utm medium=sidebar&utm campaign=C13 en.wikipedia.org&uselang=en

Help:Contents

Help:Introduction

Wikipedia:Community portal

Special:RecentChanges

Wikipedia:File upload wizard

Main Page

Special:Search

Help:Introduction

Special:MyContributions

Special:MyTalk

عجينة الحجر

Frittenporzellan

Frittkeraamika

Fritware

Ceramica vitrea

ソフトペースト

Fritware

Фриттовый фарфор

Đồ gốm frit

Special:EntityPage/Q1458831#sitelinks-wikipedia

Fritware

Updating...x

Text je dostupný za podmienok Creative

Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License 3.0 Unported; prípadne za ďalších

podmienok.

Podrobnejšie informácie nájdete na stránke Podmienky

použitia.